The Female Advocate

Mary Scott's The Female Advocate; a poem occasioned by reading Mr. Duncombe's Feminead (1775) is both a celebration of women's literary achievements, as well as an impassioned piece of advocacy for women's right to literary self-expression.

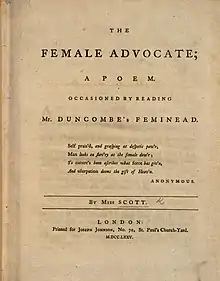

Title page of Mary Scott's The Female Advocate (1775) | |

| Author | Mary Scott |

|---|---|

| Subject | literary women |

| Genre | poetry |

| Published | London |

| Publisher | Joseph Johnson |

Publication date | 1775 |

| Pages | viii+41 pp. |

| Website | Google Books |

The poem

The Female Advocate takes John Duncombe's The Feminead: or, female genius. A poem (1754) as its inspiration. Scott expresses gratitude and admiration for Duncombe, then justifies her own project with her stated wish to expand his original list of "female geniuses", as well as to include some of those who came to prominence since he wrote (page v).

Duncombe's poem is celebratory; it rehearses the accomplishments of women writers of the mid-eighteenth-century. Scott cast further back in time in order to "tell what bright daughters BRITAIN once could boast" (l. 25) and introduces a series of women from the previous two centuries that would have already been familiar to most of her readers, beginning with the learned Protestant sixth wife of Henry VIII, Catherine Parr. She continues chronologically into the quarter-century between when Duncombe's poem was published two decades earlier and the time of her own writing. Her poem combines the tradition of the catalogue of exemplary women that Duncombe follows, with that of another genre that would also have been familiar to her readers: the defence of women.

Scott's poem consists of 522 lines of heroic couplets. It is dedicated to her close friend, Mary Steele,[1] and contains several references to people within their circle.[2]

Names

Pastoral pseudonyms, or noms de plumes, were popular in the eighteenth century, and Scott uses them in this poem, both widely known ones such as "Orinda" for Katherine Philips, as well as pen names employed in a more limited way, within her own circle. Female writers often published anonymously. Scott includes two anonymous writers in the body of the poem[3] and mentions a third in the introduction.

Literary figures treated in The Female Advocate

In the introduction

In the introduction, Scott mentions four writers who had "started up since the writing of this little piece":[4] Hester Chapone (1727–1801),[5] Hannah More, Phillis Wheatley, and the unnamed author of "poems by a lady" "lately published" by G. Robinson in Paternoster Row.[6] She implies that there is no shortage of subjects: "Authors have appeared with honour, in almost every walk of literature."

In the poem

- Catherine Parr (1512–1548): queen consort and author of three works

- Jane Grey (1537–1554): reputation for excellent humanist education

- Elizabeth Tudor (1533–1603): monarch and sometime poet

- Margaret Roper (née More; 1505–1544)[7]

- Elizabeth Dauncey (née More; 1506–1564)[7]

- Cecily Heron (née More; born 1507–?)[7]

- Mary Basset (née Roper; also Clarke; c. 1523 – 1572)[7]

- Anne Seymour (later Dudley; 1538–1588)[7]

- Margaret Seymour (b. 1540)[7]

- Jane Seymour (1541–1561)[7]

- Anne Bacon (née Cooke; 1528–1610)[7]

- Elizabeth Russell (née Cooke; 1528–1609)[7]

- Mildred Cooke (1526–1589)[7]

- Catherine Killigrew (née Cooke; c. 1530 – 1583)[7]

- Margaret Rowlett (née Cooke; d. 1558), sister of Ann Bacon, Mildred Cooke, Elizabeth Russell[7]

- Margaret Cavendish (née Lucas; c. 1624 – 1674): philosopher, poet, scientist, fiction writer, playwright

- Anne Killigrew (1660–1685): poet and painter

- Katherine Philips (née Fowler; 1631/2 – 1664): poet; also included in Duncombe's The Feminead

- Rachel Russell (née Wriothesley; c. 1636 – 1723): known for her published correspondence

- Mary Monck (née Molesworth; 1677? – 1715): poet

- Mary Chudleigh (née Lee; August 1656–1710): feminist poet and intellectual

- Constantia Grierson (née Crawley; c. 1705 – 1732): editor, poet, classical scholar

- Mary Barber (c. 1685 – c. 1755): poet

- Mary Chandler (1687–1745): poet

- Mary Jones (1707–1778): poet

- Mary Masters (1698? – 1761?): anthologist/biographer

- Elizabeth Cooper (née Price; 1698? – 1761?): noted by Scott for her edited anthology of poetry, The Muse's Library, with which she "did'st pierce the shades of gothic night" by collecting poetry of earlier periods (l. 235)

- Sarah Fielding (1710–1768): novelist

- Elizabeth Tollet (1694–1754): poet, philosopher, and translator

- Charlotte Lennox (née Ramsay; c. 1730 – 1804): novelist, playwright, poet

- Elizabeth Griffith (1727–1793): dramatist, fiction writer, essayist

- Anne Steele / "Theodosia" (1717–1778): hymn writer and essayist; not openly named in the poem; centre of Scott's own literary circle and aunt of Mary Steele, to whom The Female Advocate is dedicated

- Frances Greville (née Macartney; c. 1724 – 1789): poet

- Mary Whateley (later Darwall; 1738–1825):[8] poet and playwright

- Catharine Macaulay (née Sawbridge; 1731–1791): historian

- Anna Williams (1706–1783): poet

- Sarah Pennington (née Moore; c. 1720 – 1783): author of conduct literature

- Elizabeth Montagu (née Robinson; 1718–1800): patron of the arts, salonnière, literary critic, writer, Blue Stocking

- Dorothea Celesia (bap. 1738, died 1790): poet, playwright, translator

- Catherine Talbot (1721–1770): essayist and Blue Stocking

- Rose Roberts (1730–1788): not openly named in the poem[9]

- Jael Pye (née Mendez; c. 1737 – 1782): author of four works; not openly named in the poem[10]

- Anna Laetitia Barbauld (née Aikin; 1743–1825): poet, essayist, literary critic, editor, author of children's literature

- John Duncombe (writer) (1729–1786): author of The Feminead (1754)

- Thomas Seward (1708–1790): author of The Female Right to Literature, in a Letter to a Young Lady from Florence (1766)

- Anna Seward / "Athenia" (1742–1809): poet; mentioned by Scott as the beneficiary of Thomas Seward's progressive ideas about female education

- William Steele IV / "Philander" (1715–1785): Mary Steele's father[11]

In the footnotes

- Katherine Grey (1540–1568)

- Mary Sidney (later Herbert; 1561–1621): poet

- Laetitia Pilkington (c. 1709 – 1750): poet; included in Duncombe's The Feminead

References

- The general consensus had been that Scott had dedicated the poem to Anne Steele, but recent research indicates that the dedicatee was rather Anne's niece Mary. See Whelan, Timothy. "Mary Scott, Sarah Froud, and the Steele Literary Circle: A Revealing Annotation to The Female Advocate." Huntington Library Quarterly Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 435–452.

- Miss Williams of Yeovil, a close friend of both Scott and Mary Steele, is "Celia" (ll. 103–110), for example; and several lines toward the end of the poem (ll. 500–508) are considered to refer to Richard Pulteney (1730-1801), a friend and mentor. See Whelan, Timothy. "References to Members of the Steele Circle in The Female Advocate" nonconformistwomenwriters1650-1850.com

- Tentatively identified as Rose Roberts and Jael Pye

- Scott, Mary. The Female Advocate; a poem occasioned by reading Mr. Duncombe's Feminead (London: Joseph Johnson, 1775, p. vii). Google Books

- Though Chapone is treated in Duncombe's The Feminead and so cannot have been a new writer to Scott.

- Possibly this publication: Unknown, [Woman]. Original poems, translations, and imitations, From the French, &c. By a lady. The Women's Print History Project, 2019, title ID 5349Accessed 2022-06-25. WPHP

- Scott refers to this group of a dozen or so accomplished women of the Renaissance as "Mores, Seymours, Cokes, a bright assemblage" (l. 83).

- Fullard, Joyce. "Notes on Mary Whateley and Mary Scott's The Female Advocate." The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 1987 81:1, 74-76. DOI

- "Roberts, Rose." The Women's Print History Project, 2019, Person ID 2537. Accessed 2022-06-25. WPHP.

- Pye, Jael Henrietta. Poems. By a lady. The Women's Print History Project, 2019, title ID 4652. Accessed 2022-06-25. WPHP

- Whelan, Timothy. "References to Members of the Steele Circle in The Female Advocate" nonconformistwomenwriters1650-1850.com

Electronic text

- Full text at Scott, Mary. The Female Advocate; a poem occasioned by reading Mr. Duncombe's Feminead (London: Joseph Johnson, 1775). Google Books