Hero's journey

In narratology and comparative mythology, the hero's journey, or the monomyth, is the common template of stories that involve a hero who goes on an adventure, is victorious in a decisive crisis, and comes home changed or transformed.

Earlier figures had proposed similar concepts, including psychoanalyst Otto Rank and amateur anthropologist Lord Raglan.[1] Eventually, hero myth pattern studies were popularized by Joseph Campbell, who was influenced by Carl Jung's analytical psychology. Campbell used the monomyth to analyze and compare religions. In his famous book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), he describes the narrative pattern as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Campbell's theories regarding the concept of a "monomyth" have been the subject of criticism from scholars, particularly folklorists (scholars active in folklore studies), who have dismissed the concept as a non-scholarly approach suffering from source-selection bias, among other criticisms. More recently, the hero's journey has been analyzed as an example of the sympathetic plot, a universal narrative structure in which a goal-directed protagonist confronts obstacles, overcomes them, and eventually reaps rewards.[1][2]

Background

The study of hero myth narratives can be traced back to 1871 with anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor's observations of common patterns in the plots of heroes' journeys.[3] In narratology and comparative mythology, others have proposed narrative patterns such as psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909 and amateur anthropologist Lord Raglan in 1936.[4] Both Rank and Raglan have lists of cross-cultural traits often found in the accounts of mythical heroes[5][6] and discuss hero narrative patterns in terms of Freudian psychoanalysis and ritualism.[1] According to Robert Segal, "The theories of Rank, Campbell, and Raglan typify the array of analyses of hero myths."[3]

Terminology

Campbell borrowed the word monomyth from James Joyce's Finnegans Wake (1939). Campbell was a notable scholar of Joyce's work and in A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake (1944) co-authored the seminal analysis of Joyce's final novel.[7][8] Campbell's singular the monomyth implies that the "hero's journey" is the ultimate narrative archetype, but the term monomyth has occasionally been used more generally, as a term for a mythological archetype or a supposed mytheme that re-occurs throughout the world's cultures.[9][10] Omry Ronen referred to Vyacheslav Ivanov's treatment of Dionysus as an "avatar of Christ" (1904) as "Ivanov's monomyth".[11]

The phrase "the hero's journey", used in reference to Campbell's monomyth, first entered into popular discourse through two documentaries. The first, released in 1987, The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was accompanied by a 1990 companion book, The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work (with Phil Cousineau and Stuart Brown, eds.). The second was Bill Moyers's series of seminal interviews with Campbell, released in 1988 as the documentary (and companion book) The Power of Myth. Cousineau in the introduction to the revised edition of The Hero's Journey wrote "the monomyth is in effect a meta myth, a philosophical reading of the unity of mankind's spiritual history, the Story behind the story".[12]

Summary

In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell summarizes the narrative pattern of the monomyth as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.[13]

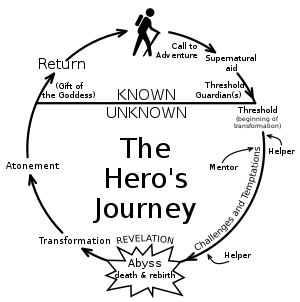

Campbell describes 17 stages of the monomyth. Not all monomyths necessarily contain all 17 stages explicitly; some myths may focus on only one of the stages, while others may deal with the stages in a somewhat different order. In the terminology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the stages are the individual mythemes which are "bundled" or assembled into the structure of the monomyth.[14]

The 17 stages may be organized in a number of ways, including division into three "acts" or sections:

- Departure (also Separation),

- Initiation (sometimes subdivided into A. Descent and B. Initiation) and

- Return.

In the departure part of the narrative, the hero or protagonist lives in the ordinary world and receives a call to go on an adventure. The hero is reluctant to follow the call but is helped by a mentor figure.

The initiation section begins with the hero then traversing the threshold to an unknown or "special world", where he faces tasks or trials, either alone or with the assistance of helpers. The hero eventually reaches "the innermost cave" or the central crisis of his adventure, where he must undergo "the ordeal" where he overcomes the main obstacle or enemy, undergoing "apotheosis" and gaining his reward (a treasure or "elixir").

In the return section, the hero must return to the ordinary world with his reward. He may be pursued by the guardians of the special world, or he may be reluctant to return and may be rescued or forced to return by intervention from the outside. The hero again traverses the threshold between the worlds, returning to the ordinary world with the treasure or elixir he gained, which he may now use for the benefit of his fellow man. The hero himself is transformed by the adventure and gains wisdom or spiritual power over both worlds.

| Act | Campbell (1949) | Christopher Vogler (2007)[15] |

|---|---|---|

| I. Departure |

|

|

| II. Initiation |

|

|

| III. Return |

|

|

Campbell's seventeen stages

The Call to Adventure

The hero begins in a situation of normality from which some information is received that acts as a call to head off into the unknown. According to Campbell, this region is represented by

a distant land, a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, superhuman deeds, and impossible delight. The hero can go forth of their own volition to accomplish the adventure, as did Theseus when he arrived in his father's city, Athens, and heard the horrible history of the Minotaur; or they may be carried or sent abroad by some benign or malignant agent as was Odysseus, driven about the Mediterranean by the winds of the angered god, Poseidon. The adventure may begin as a mere blunder... or still, again, one may be only casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man. Examples might be multiplied, ad infinitum, from every corner of the world.[16]

Refusal of the Call

Often when the call is given, the future hero first refuses to heed it. This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the person in his current circumstances. Campbell says that

Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or "culture," the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved. His flowering world becomes a wasteland of dry stones and his life feels meaningless—even though, like King Minos, he may through titanic effort succeed in building an empire of renown. Whatever house he builds, it will be a house of death: a labyrinth of cyclopean walls to hide from him his Minotaur. All he can do is create new problems for himself and await the gradual approach of his disintegration.[17]

Supernatural Aid

Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously, their guide and magical helper appears or becomes known. More often than not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more talismans or artifacts that will aid them later in their quest.[18] Campbell writes:

What such a figure represents is benign, protecting power of destiny. The fantasy is a reassurance—promise that the peace of Paradise, which was known first within the mother womb, is not to be lost; that it supports the present and stands in the future as well as in the past (is omega as well as alpha); that though omnipotence may seem to be endangered by the threshold of the world. One has only to know and trust, and the ageless guardians will appear. Having responded to their own call, and continuing to follow courageously as the consequences unfold, the hero finds all the forces of the unconscious at their side. Mother Nature herself supports the mighty task. And in so far as the hero's act coincides with that for which their society itself is ready, they seem to ride on the great rhythm of the historical process.[19]

The Crossing of the First Threshold

This is the point where the hero actually crosses into the field of adventure, leaving the known limits of their world and venturing into an unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are unknown. Campbell tells us,

With the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the "threshold guardian" at the entrance to the zone of magnified power. Such custodians bound the world in four directions—also up and down—standing for the limits of the hero's present sphere, or life horizon. Beyond them is darkness, the unknown, and danger; just as beyond the parental watch is a danger to the infant and beyond the protection of his society danger to the members of the tribe. The usual person is more than content, he is even proud, to remain within the indicated bounds, and popular belief gives him every reason to fear so much as the first step into the unexplored.

...

The adventure is always and everywhere a passage beyond the veil of the known into the unknown; the powers that watch at the boundary are dangerous; to deal with them is risky, yet for anyone with competence and courage the danger fades.[20]

Belly of the Whale

The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero's known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows a willingness to undergo a metamorphosis. When first entering the stage the hero may encounter a minor danger or setback. According to Campbell,

The idea that the passage of the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth is symbolized in the worldwide womb image of the belly of the whale. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died.

...

This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation. ... [I]nstead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again. The disappearance corresponds to the passing of a worshiper into the temple—where he is to be quickened by the recollection of who and what he is, namely dust and ashes unless immortal. The temple interior, the belly of the whale, and the heavenly land beyond, above, and below the confines of the world, are one and the same. That is why the approaches of and entrances to temples are flanked and defended by colossal gargoyles [equivalent to] the two rows of teeth of the whale. They illustrate the fact that the devotee at the moment of entry into a temple undergoes a metamorphosis. ... Once inside he may be said to have died to time and returned to the World Womb, the World Navel, the Earthly Paradise. ... Allegorically, then, the passage into a temple and the hero-dive through the jaws of the whale are identical adventures, both denoting in picture language, the life-centering, life-renewing act.[21]

In the exemplary Book of Jonah, the eponymous Israelite refuses God's command to prophesy the destruction of Nineveh and attempts to flee by sailing to Tarshish. A storm arises, and the sailors cast lots to determine that Jonah is to blame. He allows himself to be thrown overboard to calm the storm, and is saved from drowning by being swallowed by a "great fish". Over three days, Jonah commits to God's will, and he is vomited safely onto the shore. He subsequently goes to Nineveh and preaches to its inhabitants.[22] Jonah's passage through the belly of the whale can be viewed as a symbolic death and rebirth in Jungian analysis.[23]

In The Power of Myth, Campbell agrees with Bill Moyers that the original Star Wars film's trash-compactor scene on the Death Star is a strong example of this step of the journey.[24]

The Road of Trials

The road of trials is a series of tests that the hero must undergo to begin the transformation. Often the hero fails one or more of these tests, which often occur in threes. Eventually, the hero will overcome these trials and move on to the next step. Campbell explains that

Once having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials. This is a favorite phase of the myth-adventure. It has produced a world literature of miraculous tests and ordeals. The hero is covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom he met before his entrance into this region. Or it may be that he here discovers for the first time that there is a benign power everywhere supporting him in his superhuman passage.

...

The original departure into the land of trials represented only the beginning of the long and really perilous path of initiatory conquests and moments of illumination. Dragons have now to be slain and surprising barriers passed—again, again, and again. Meanwhile, there will be a multitude of preliminary victories, unsustainable ecstasies, and momentary glimpses of the wonderful land.[25]

The Meeting with the Goddess

This is where the hero gains items given to him that will help him in the future. Campbell proposes that

The ultimate adventure, when all the barriers and ogres have been overcome, is commonly represented as a mystical marriage of the triumphant hero-soul with the Queen Goddess of the World. This is the crisis at the nadir, the zenith, or at the uttermost edge of the earth, at the central point of the cosmos, in the tabernacle of the temple, or within the darkness of the deepest chamber of the heart.

...

The meeting with the goddess (who is incarnate in every woman) is the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love (charity: amor fati), which is life itself enjoyed as the encasement of eternity.

And when the adventurer, in this context, is not a youth but a maid, she is the one who, by her qualities, her beauty, or her yearning, is fit to become the consort of an immortal. Then the heavenly husband descends to her and conducts her to his bed—whether she will or not. And if she has shunned him, the scales fall from her eyes; if she has sought him, her desire finds its peace.[26]

Woman as the Temptress

In this step, the hero faces those temptations, often of a physical or pleasurable nature, that may lead them to abandon or stray from their quest, which does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman. A woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual journey. Campbell relates that

The crux of the curious difficulty lies in the fact that our conscious views of what life ought to be seldom correspond to what life really is. Generally, we refuse to admit within ourselves, or within our friends, the fullness of that pushing, self-protective, malodorous, carnivorous, lecherous fever which is the very nature of the organic cell. Rather, we tend to perfume, whitewash, and reinterpret; meanwhile imagining that all the flies in the ointment, all the hairs in the soup, are the faults of some unpleasant someone else. But when it suddenly dawns on us or is forced to our attention that everything we think or do is necessarily tainted with the odor of the flesh, then, not uncommonly, there is experienced a moment of revulsion: life, the acts of life, the organs of life, a woman in particular as the great symbol of life, become intolerable to the pure, the pure, pure soul. ... The seeker of the life beyond life must press beyond [the woman], surpass the temptations of her call, and soar to the immaculate ether beyond.[27]

Atonement with the Father/Abyss

In this step, the hero must confront and be initiated by whatever holds the ultimate power in their life. In many myths and stories, this is the father or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving into this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity, it does not have to be a male—just someone or something with incredible power. Per Campbell,

Atonement consists in no more than the abandonment of that self-generated double monster—the dragon thought to be God (superego) and the dragon thought to be Sin (repressed id). But this requires an abandonment of the attachment to ego itself, and that is what is difficult. One must have faith that the father is merciful, and then a reliance on that mercy. Therewith, the center of belief is transferred outside of the bedeviling god's tight scaly ring, and the dreadful ogres dissolve. It is in this ordeal that the hero may derive hope and assurance from the helpful female figure, by whose magic (pollen charms or power of intercession) they are protected through all the frightening experiences of the father's ego-shattering initiation. For if it is impossible to trust the terrifying father-face, then one's faith must be centered elsewhere (Spider Woman, Blessed Mother); and with that reliance for support, one endures the crisis—only to find, in the end, that the father and mother reflect each other, and are in essence the same.[28]

Campbell later expounds:

The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its peculiar blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. They behold the face of the father, understand — and the two are atoned.[29]

Apotheosis

This is the point of realization in which a greater understanding is achieved. Armed with this new knowledge and perception, the hero is resolved and ready for the more difficult part of the adventure. Campbell discloses that

Those who know, not only that the Everlasting lies in them, but that what they, and all things, really are is the Everlasting, dwell in the groves of the wish-fulfilling trees, drink the brew of immortality, and listen everywhere to the unheard music of eternal concord.[30]

The Ultimate Boon

The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is what the hero went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve to prepare and purify the hero for this step since in many myths the boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail. Campbell confers that

The gods and goddesses then are to be understood as embodiments and custodians of the elixir of Imperishable Being but not themselves the Ultimate in its primary state. What the hero seeks through his intercourse with them is therefore not finally themselves, but their grace, i.e., the power of their sustaining substance. This miraculous energy-substance and this alone is the Imperishable; the names and forms of the deities who everywhere embody, dispense, and represent it come and go. This is the miraculous energy of the thunderbolts of Zeus, Yahweh, and the Supreme Buddha, the fertility of the rain of Viracocha, the virtue announced by the bell rung in the Mass at the consecration, and the light of the ultimate illumination of the saint and sage. Its guardians dare release it only to the duly proven.[31]

Refusal of the Return

Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may not want to return to the ordinary world to bestow the boon onto their fellow beings. Campbell continues:

When the hero-quest has been accomplished, through penetration to the source, or through the grace of some male or female, human or animal personification, the adventurer still must return with his life-transmuting trophy. The full round, the norm of the monomyth, requires that the hero shall now begin the labor of bringing the runes of wisdom, the Golden Fleece, or his sleeping princess, back into the kingdom of humanity, where the boon may redound to the renewing of the community, the nation, the planet, or the ten thousand worlds. But the responsibility has been frequently refused. Even Gautama Buddha, after his triumph, doubted whether the message of realization could be communicated, and saints are reported to have died while in the supernal ecstasy. Numerous indeed are the heroes fabled to have taken up residence forever in the blessed isle of the unaging Goddess of Immortal Being.[32]

The Magic Flight

Sometimes the hero must escape with the boon if it is something that the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it. Campbell argues that

If the hero in his triumph wins the blessing of the goddess or the god and is then explicitly commissioned to return to the world with some elixir for the restoration of society, the final stage of his adventure is supported by all the powers of his supernatural patron. On the other hand, if the trophy has been attained against the opposition of its guardian, or if the hero's wish to return to the world has been resented by the gods or demons, then the last stage of the mythological round becomes a lively, often comical, pursuit. This flight may be complicated by marvels of magical obstruction and evasion.[33]

Rescue from Without

Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest, often they must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life, especially if the hero has been wounded or weakened by the experience. Campbell elucidates,

The hero may have to be brought back from his supernatural adventure by assistance from without. That is to say, the world may have to come and get him. For the bliss of the deep abode is not lightly abandoned in favor of the [disorder] of the wakened state. ... Society is jealous of those who remain away from it and will come knocking at the door. If the hero ... is unwilling, the disturber suffers an ugly shock; but on the other hand, if the summoned one is only delayed—sealed in by the [deathlike rapture] of a perfect being ... an apparent rescue is effected, and the adventurer returns.[34]

The Crossing of the Return Threshold

Campbell says in The Hero with a Thousand Faces that "The returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world."[35] The goal of the return is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest and to integrate it into society. Campbell writes,

Many failures attest to the difficulties of this life-affirmative threshold. The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the [ups and downs] of life. Why re-enter such a world? Why [share] the experience of transcendental bliss? As dreams that were momentous by night may seem simply silly in the light of day, so the poet and the prophet can discover themselves playing the idiot before [others]. The easy thing is to commit the whole community to the devil and retire again into [bliss]. But if some spiritual obstetrician has drawn the shimenawa across the retreat, then the work of [distilling eternal truth] cannot be avoided.[36]

Master of the Two Worlds

For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable and competent in both the inner and outer worlds. Campbell demonstrates that

Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back—not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other—is the talent of the master. The Cosmic Dancer, declares Nietzsche, does not rest heavily in a single spot, but gaily, lightly, turns and leaps from one position to another. It is possible to speak from only one point at a time, but that does not invalidate the insights of the rest.[37]

Discussing this stage, Campbell cites the Apostles of Jesus, who had become selfless in their devotion by the time of their master's transfiguration, as well as the similar orthodoxy presented by Krishna, who said, "He who does My work and regards Me as the Supreme Goal ... without hatred for any creature—he comes to Me."[38] Campbell goes on to illustrate that

The individual, through prolonged psychological disciplines, gives up completely all attachment to his personal limitations, idiosyncrasies, hopes and fears, no longer resists the self-annihilation that is prerequisite to rebirth in the realization of truth, and so becomes ripe, at last, for the great at-one-ment. His personal ambitions being totally dissolved, he no longer tries to live but willingly relaxes to whatever may come to pass in him; he becomes, that is to say, an anonymity.[38]

Freedom to Live

In this step, mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past. Campbell declares,

The hero is the champion of things becoming, not of things become, because he is. "Before Abraham was, I AM." He does not mistake apparent changelessness in time for the permanence of Being, nor is he fearful of the next moment (or of the "other thing"), as destroying the permanent with its change. [Quoting Ovid's Metamorphoses:] "Nothing retains its own form; but Nature, the greater renewer, ever makes up forms from forms. Be sure that nothing perishes in the whole universe; it does but vary and renew its form." Thus the next moment is permitted to come to pass.[39]

In popular culture and literature

The monomyth concept has been popular in American literary studies and writing guides since at least the 1970s. Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood film producer and writer, created a 7-page company memo, A Practical Guide to The Hero with a Thousand Faces,[40] based on Campbell's work. Vogler's memo was later developed into the late 1990s book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

George Lucas's 1977 film Star Wars was classified as monomyth almost as soon as it came out.[41][42] In addition to the extensive discussion between Campbell and Bill Moyers broadcast in 1988 as The Power of Myth, Lucas gave an extensive interview in which he states that after completing American Graffiti, "it came to me that there really was no modern use of mythology... so that's when I started doing more strenuous research on fairy tales, folklore, and mythology, and I started reading Joe's books. ... It was very eerie because in reading The Hero with a Thousand Faces I began to realize that my first draft of Star Wars was following classical motifs".[43] Moyers and Lucas also met for a 1999 interview to further discuss the impact of Campbell's work on Lucas's films.[44] In addition, the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution sponsored an exhibit during the late 1990s called Star Wars: The Magic of Myth which discussed the ways in which Campbell's work shaped the Star Wars saga.[45]

Numerous literary works of popular fiction have been identified by various authors as examples of the monomyth template, including Spenser's The Faerie Queene,[46] Melville's Moby Dick,[47] Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre,[48] works by Charles Dickens, William Faulkner, Somerset Maugham, J. D. Salinger,[49] Ernest Hemingway,[50] Mark Twain,[51] W. B. Yeats,[52] C. S. Lewis,[53] J. R. R. Tolkien,[54] Seamus Heaney[55] and Stephen King,[56] Plato's - Allegory of the Cave, Homer's - Odyssey, Frank Baum's - The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Lewis Carroll's - Alice's Adventures in Wonderland among many others.

Stanley Kubrick introduced Arthur C. Clarke to the book "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" by Joseph Campbell during the writing of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Arthur C. Clarke called Joseph Campbell's book "very stimulating" in his diary entry.[57]

Feminist literature and female heroines within the monomyth

Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë's character Jane Eyre is an important figure in illustrating heroines and their place within the hero's journey. Charlotte Brontë sought to craft a unique female character that the term "Heroine" could fully encompass.[58] Jane Eyre is a Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story common in Victorian fiction, also referred to as an apprenticeship novel, that shows moral and psychological development of the protagonist as they grow into adults.[58]

Jane, being a middle-class Victorian woman, would face entirely different obstacles and conflict than her male counterparts of this era such as Pip in Great Expectations. This would change the course of the hero's journey because Brontë was able to recognize the fundamental conflict that plagued women of this time (one main source of this conflict being women's relationship with power and wealth and often being distant from obtaining both).[59]

Charlotte Brontë takes Jane's character a step further by making her more passionate and outspoken than other Victorian women of this time. The abuse and psychological trauma Jane receives from the Reeds as a child cause her to develop two central goals for her to complete her heroine journey: a need to love and to be loved, and her need for liberty.[58] Jane accomplishes part of attaining liberty when she castigates Mrs. Reed for treating her poorly as a child, obtaining the freedom of her mind.

As Jane grows throughout the novel, she also becomes unwilling to sacrifice one of her goals for the other. When Rochester, the "temptress" in her journey, asks her to stay with him as his mistress, she refuses, as it would jeopardize the freedom she had struggled to obtain. She instead returns after Rochester's wife passes away, now free to marry him and able to achieve both of her goals and complete her role in the hero's journey.[58]

While the story ends with a marriage trope, Brontë has Jane return to Rochester after several chances to grow, allowing her to return as close to equals as possible while also having fleshed out her growth within the heroine's journey. Since Jane is able to marry Rochester as an equal and through her own means, this makes Jane one of the most satisfying and fulfilling heroines in literature and in the heroine's journey.

Psyche

The story Metamorphoses (also known as The Golden Ass) by Apuleius in 158 A.D. is one of the most enduring and retold myths involving the hero's journey.[60] The tale of Cupid and Psyche is a frame tale—a story within a story—and is one of the thirteen stories within "Metamorphoses." The use of the frame tale puts both the storyteller and reader into the novel as characters, which explores the main aspect of the hero's journey due to it being a process of tradition where literature is written and read.[60]

Cupid and Psyche's tale has become the most popular of Metamorphoses and has been retold many times with successful iterations dating as recently as 1956's Till We Have Faces by C.S. Lewis.[60] Much of the tale's captivation comes from the central heroine, Psyche. Psyche's place within the hero's journey is fascinating and complex as it revolves around her characteristics of being a beautiful woman and the conflict that arises from it. Psyche's beauty causes her to become ostracized from society because no male suitors will ask to marry her as they feel unworthy of her seemingly divine beauty and kind nature. Psyche's call to adventure is involuntary: her beauty enrages the goddess Venus, which results in Psyche being banished from her home.[60]

Part of what makes Psyche such a polarizing figure within the heroine's journey is her nature and ability to triumph over the unfair trials set upon her by Venus. Psyche is given four seemingly impossible tasks by Venus to get her husband Cupid back: the sorting of the seeds, the fleecing of the golden rams, collecting a crystal jar full of the water of death and retrieving a beauty creme from Hades.[60] The last task is considered to be one of the most monumental and memorable tasks ever to be taken on in the history of the heroine's journey due to its difficulty. Yet, Psyche is able to achieve each task and complete her ultimate goal of becoming an immortal goddess and moving to Mount Olympus to be with her husband Cupid for all eternity.

During the early 19th century, a Norwegian version of the Psyche myth was collected in Finnmark by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, who is still considered to be Norway's answer to the Brothers Grimm. It was published in their legendary anthology Norwegian Folktales. The fairy tale is titled "East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon".

Self-help movement and therapy

Poet Robert Bly, Michael J. Meade, and others involved in the mythopoetic men's movement have also applied and expanded the concepts of the hero's journey and the monomyth as a metaphor for personal spiritual and psychological growth.[61][62]

Characteristic of the mythopoetic men's movement is a tendency to retell fairy tales and engage in their exegesis as a tool for personal insight. Using frequent references to archetypes as drawn from Jungian analytical psychology, the movement focuses on issues of gender role, gender identity and wellness for modern men.[62] Advocates would often engage in storytelling with music, these acts being seen as a modern extension to a form of "new age shamanism" popularized by Michael Harner at approximately the same time.

Among its most famous advocates was the poet Robert Bly, whose book Iron John: A Book About Men was a best-seller, being an exegesis of the fairy tale "Iron John" by the Brothers Grimm.[61]

The mythopoetic men's movement spawned a variety of groups and workshops, led by authors such as Bly and Robert L. Moore.[62] Some serious academic work came out of this movement, including the creation of various magazines and non-profit organizations.[61]

Academic reception and criticism

Campbell's approach to myth, a genre of folklore, has been the subject of criticism from folklorists, academics who specialize in folklore studies. American folklorist Barre Toelken notes that few psychologists have taken the time to become familiar with the complexities of folklore, and that, historically, Jung-influenced psychologists and authors have tended to build complex theories around single versions of a tale that supports a theory or a proposal. To illustrate his point, Toelken employs Clarissa Pinkola Estés's (1992) Women Who Run with the Wolves, citing its inaccurate representation of the folklore record, and Campbell's "monomyth" approach as another. Regarding Campbell, Toelken writes, "Campbell could construct a monomyth of the hero only by citing those stories that fit his preconceived mold, and leaving out equally valid stories... which did not fit the pattern". Toelken traces the influence of Campbell's monomyth theory into other then-contemporary popular works, such as Robert Bly's Iron John: A Book About Men (1990), which he says suffers from similar source selection bias.[63]

Similarly, American folklorist Alan Dundes is highly critical of both Campbell's approach to folklore, designating him as a "non-expert" and outlining various examples of source bias in Campbell's theories, as well as media representation of Campbell as an expert on the subject of myth in popular culture. Dundes writes, "Folklorists have had some success in publicising the results of our efforts in the past two centuries such that members of other disciplines have, after a minimum of reading, believe they are qualified to speak authoritatively of folkloristic matters. It seems that the world is full of self-proclaimed experts in folklore, and a few, such as Campbell, have been accepted as such by the general public (and public television, in the case of Campbell)". According to Dundes, "there is no single idea promulgated by amateurs that have done more harm to serious folklore study than the notion of archetype".[64]

According to Northup (2006), mainstream scholarship of comparative mythology since Campbell has moved away from "highly general and universal" categories in general.[65] This attitude is illustrated by Consentino (1998), who remarks "It is just as important to stress differences as similarities, to avoid creating a (Joseph) Campbell soup of myths that loses all local flavor."[66] Similarly, Ellwood (1999) stated "A tendency to think in generic terms of people, races ... is undoubtedly the profoundest flaw in mythological thinking."[67]

Others have found the categories Campbell works with so vague as to be meaningless and lacking the support required of scholarly argument: Crespi (1990), writing in response to Campbell's filmed presentation of his model, characterized it as "unsatisfying from a social science perspective. Campbell's ethnocentrism will raise objections, and his analytic level is so abstract and devoid of ethnographic context that myth loses the very meanings supposed to be embedded in the 'hero'."[68]

In a similar vein, American philosopher John Shelton Lawrence and American religious scholar Robert Jewett have discussed an "American Monomyth" in many of their books, The American Monomyth, The Myth of the American Superhero (2002), and Captain America and the Crusade Against Evil: The Dilemma of Zealous Nationalism (2003). They present this as an American reaction to the Campbellian monomyth. The "American Monomyth" storyline is: "A community in a harmonious paradise is threatened by evil; normal institutions fail to contend with this threat; a selfless superhero emerges to renounce temptations and carry out the redemptive task; aided by fate, his decisive victory restores the community to its paradisiacal condition; the superhero then recedes into obscurity."[69]

The monomyth has also been criticized for focusing on the masculine journey. The Heroine's Journey (1990)[70] by Maureen Murdock and From Girl to Goddess: The Heroine's Journey Through Myth and Legend (2010) by Valerie Estelle Frankel both set out what they consider the steps of the female hero's journey, which is different from Campbell's monomyth.[71] Likewise, The Virgin's Promise, by Kim Hudson, articulates an equivalent feminine journey, to parallel the masculine hero's journey, which concerns personal growth and "creative, spiritual, and sexual awakening" rather than an external quest.[72]

According to a 2014 interview between filmmaker Nicole L. Franklin and artist and comic book illustrator Alice Meichi Li, a hero's journey is "the journey of someone who has privilege. Regardless of the protagonist is male or female, a heroine does not start out with privilege." Being underprivileged, to Li, means that the heroine may not receive the same level of social support enjoyed by the hero in a traditional mythic cycle, and rather than return from her quest as both hero and mentor the heroine instead returns to a world in which she or he is still part of an oppressed demographic. Li adds, "They're not really bringing back an elixir. They're navigating our patriarchal society with unequal pay and inequalities. In the final chapter, they may end up on equal footing. But when you have oppressed groups, all you can hope for is to get half as far by working twice as hard."[73]

Science-fiction author David Brin in a 1999 Salon article criticized the monomyth template as supportive of "despotism and tyranny", indicating that he thinks modern popular fiction should strive to depart from it to support more progressive values.[74]

See also

Other mythology

- Allegory of the Cave

- Dying-and-rising deity

- Gregory Nagy (professor of classics)

- How to Kill a Dragon (1995)

- The Myth of the Birth of the Hero (1909)

- The Pilgrim's Progress (1678)

- Vladimir Propp (Russian folklorist)

Narratology and writing instructions

References

- Singh, Manvir (July 2021). "The Sympathetic Plot, Its Psychological Origins, and Implications for the Evolution of Fiction". Emotion Review. 13 (3): 183–198. doi:10.1177/17540739211022824. ISSN 1754-0739. S2CID 235779612.

- "Why Are So Many Movies Basically the Same? | Psychology Today". www.psychologytoday.com. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- Segal, Robert; Raglan, Lord; Rank, Otto (1990). "Introduction: In Quest of the Hero". In Quest of the Hero. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691020620.

- Green, Thomas A. (1997). Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art. ABC-CLIO. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-87436-986-1.

- Lord Raglan. The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama by Lord Raglan, Dover Publications, 1936

- Segal, Robert; Dundes, Alan; Raglan, Lord; Rank, Otto (1990). In Quest of the Hero. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691020620.

- Campbell, Joseph; Robinson, Henry Morton (1944). A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949. p. 30, n35. "At the carry four with awlus plawshus, their happyass cloudious! And then and too the trivials! And their bivouac! And his monomyth! Ah ho! Say no more about it! I'm sorry!" James Joyce, Finnegans Wake. NY: Viking (1939) p. 581

- Luhan, Mabel Dodge (1987) [1937]. "Foreword". Edge of Taos Desert: An Escape to Reality. Foreword by John Collier. p. viii.

The myth is obviously related to what one might call the monomyth of paradise regained that has been articulated and transformed in a variety of ways since the early European explorations.

- Ashe, Steven (2008). Qabalah of 50 Gates. p. 21.

those aspects of legend that are symbolically equivalent within the folklore of different cultures

- Clayton, J. Douglas, ed. (1989). Issues in Russian Literature Before 1917. p. 212.

Dionysus, Ivanov's 'monomyth,' as Omry Ronen has put it, is the symbol of the symbol. One could also name Dionysus, the myth of the myth, the meta myth which signifies the very principle of mediation, [...]

- Campbell 2003, p. xxi.

- Campbell 1949, p. 23.

- Lévi-Strauss gave the term "mytheme" wide circulation from the 1960s, in 1955 he used "gross constituent unit", in Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1955). "The Structural study of myth". Journal of American Folklore. 68 (270): 428–444. doi:10.2307/536768. ISSN 0021-8715. JSTOR 536768. OCLC 1782260. S2CID 46007391. reprinted as "The structural study of myth", Structural Anthropology, 1963:206-31; "the true constituent units of a myth are not the isolated relations but bundles of such relations" (Lévi-Strauss 1963:211). The term mytheme first appears in Lévi-Strauss's 1958 French version of the work.

- Vogler 2007.

- Campbell 2008, p. 48.

- Campbell 2008, p. 49.

- Campbell 2008, p. 57.

- Campbell 2008, p. 59.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 64, 67–68.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 74, 77.

- Jonah 1–3

- Betts, John (January 19, 2013). "The Belly of the Whale | Jungian Analysis". Jungian Psychoanalysis. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- "The Hero's Adventure". The Power of Myth. Season 1. Episode 1. 1988. Event occurs at 24:30. PBS.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 81, 90.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 91, 99.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 101–2.

- Campbell 2008, p. 110.

- Campbell 2008, p. 125.

- Campbell 2008, p. 142.

- Campbell 2008, p. 155.

- Campbell 2008, p. 167.

- Campbell 2008, p. 170.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 178–79.

- Campbell 2008, p. 194.

- Campbell 2008, p. 189.

- Campbell 2008, pp. 196–97.

- Campbell 1949, pp. 236–237.

- Campbell 2008, p. 209.

- The Writer's Journey Archived June 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine accessed March 26, 2011

- Andrew Gordon, 'Star Wars: A Myth for Our Time', Literature/Film Quarterly 6.4 (Fall 1978): 314–26.

- Matthew Kapell, John Shelton Lawrence, Finding the Force of the Star Wars Franchise: Fans, Merchandise, & Critics, Peter Lang (2006), p. 5.

- Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind, Larsen and Larsen, 2002, pp. 541–43.

- "The Mythology of Star Wars with George Lucas and Bill Moyers". Films Media Group. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Star Wars @ NASM, Unit 1, Introduction". National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. November 22, 1997.

- Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene and the Monomyth of Joseph Campbell: Essays in Interpretation, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2000.

- Khalid Mohamed Abdullah, Ishmael's Sea Journey and the Monomyth Archetypal Theory in Melville's "Moby-Dick", California State University, Dominguez Hills, 2008.

- Justin Edward Erickson, A Heroine's Journey: The Feminine Monomyth in Jane Eyre (2012).

- Leslie Ross, Manifestations of the Monomyth in Fiction: Dickens, Faulkner, Maugham, and Salinger, University of South Dakota, 1992.

- John James Bajger, The Hemingway Hero and the Monomyth: An Examination of the Hero Quest Myth in the Nick Adams Stories, Florida Atlantic University, 2003.

- Brian Claude McKinney, The Monomyth and Mark Twain's Novels, San Francisco State College, 1967.

- William Edward McMillan, The Monomyth in W.B. Yeats' Cuchulain Play Cycle, the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, 1979.

- Stephanie L. Phillips, Ransom's Journey as a Monomyth Hero in C.S. Lewis' Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength, Hardin-Simmons University, 2006.

- Paul McCord, The Monomyth Hero in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, 1977.

- Henry Hart, Seamus Heaney, Poet of Contrary Progressions, Syracuse University Press (1993), p. 165.

- , Stephen King's "The Dark Tower": a modern myth University essay from Luleå tekniska Universitet/Språk och kultur Author: Henrik Fåhraeus; [2008].

- Rice, Julian. Kubrick's Story, Spielberg's Film. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing. p. 252.

- Bloom, Harold; Hobby, Blake (2009). The Hero's Journey (Bloom's Literary Themes). New York: Bloom's Literary Criticism. pp. 85–95. ISBN 9780791098035.

- Asienberg, Nadya (1994). Ordinary heroines: transforming the male myth. New York: Continuum. p. 26-27. ISBN 0826406521.

- Smith 1997.

- Boston Globe accessed November 3, 2009

- Use by Bly of Campbell's monomyth work accessed November 3, 2009

- Toelken 1996, p. 413.

- Dundes 2016, pp. 16–18, 25.

- Northup 2006, p. 8.

- "African Oral Narrative Traditions" in Foley, John Miles, ed., "Teaching Oral Traditions." NY: Modern Language Association, 1998, p. 183

- Ellwood, Robert, "The Politics of Myth: A Study of C.G. Jung, Mircea Eliade, and Joseph Campbell", SUNY Press, September 1999. Cf. p.x

- Crespi, Muriel (1990). "Film Reviews". American Anthropologist. 92 (4): 1104. doi:10.1525/aa.1990.92.4.02a01020.

- Jewett, Robert and John Shelton Lawrence (1977) The American Monomyth. New York: Doubleday.

- Murdock, Maureen (June 23, 1990). The Heroine's Journey: Woman's Quest for Wholeness. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 9780834828346.

- Valerie Estelle Frankel (October 19, 2010). From Girl to Goddess: The Heroine's Journey Through Myth and Legend. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-5789-2.

- Hudson, Kim (2010). The Virgin's Promise: Writing Stories of Feminine Creative, Spiritual, and Sexual Awakening. Michael Wiese Productions. p. 2010. ISBN 978-1-932907-72-8.

- "Nicole Franklin, Author at The Good Men Project". The Good Men Project. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Brin, David (June 16, 1999). "'Star Wars' despots vs. 'Star Trek' populists". Salon.

By offering valuable insights into this revered storytelling tradition, Joseph Campbell did indeed shed light on common spiritual traits that seem shared by all human beings. And I'll be the first to admit it's a superb formula — one that I've used at times in my own stories and novels. [...] It is essential to understand the radical departure taken by genuine science fiction, which comes from a diametrically opposite literary tradition—a new kind of storytelling that often rebels against those very same archetypes Campbell venerated. An upstart belief in progress, egalitarianism, positive-sum games—and the slim but real possibility of decent human institutions.

Sources

- Campbell, Joseph (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1st ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691097435. (2nd ed. 1968).

- Campbell, Joseph (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces (3rd ed.). Novato, CA: New World Library. ISBN 9781577315933.

- Campbell, Joseph (2003) [1990]. Cousineau, Phil (ed.). The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work. The Collected Works of Joseph Campbell. Introduction by Phil Cousineau, foreword by Stuart L. Brown. Novato, CA: New World Library. ISBN 978-1-60868-189-1. OCLC 52133247.

- Dundes, Alan (2016). "Folkloristics in the Twenty-First Century". In Haring, Lee (ed.). Grand Theory in Folkloristics. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253024428.

- Northup, Lesley (2006). "Myth-Placed Priorities: Religion and the Study of Myth". Religious Studies Review. 32 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0922.2006.00018.x.

- Smith, Evan (1997). The Hero Journey In Literature: Parables of Poesis. Lanham: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761805083.

- Toelken, Barre (1996). The Dynamics of Folklore. Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-1-45718071-2.

- Vogler, Christopher (2007) [1998]. The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Further reading

- Laureline, Amanieux (2011). Ce héros qui est en chacun de nous (in French). Albin Michel.

- MacKey-Kallis, Susan (2001). The Hero and the Perennial Journey Home in American Film. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1768-3.

- Moyers, Bill; Flowers, Betty Sue, eds. (1988). The Power of Myth.

- Rebillot, Paul (2017). The Hero's Journey: A Call to Adventure. Eagle Books, Germany. ISBN 978-3-946136-00-2.

- Voytilla, Stuart; Vogler, Christopher (1999). Myth & the Movies: Discovering the Myth Structure of 50 Unforgettable Films. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions. ISBN 0-941188-66-3.

External links

- Office of Resources for International and Area Studies. "Monomyth Home". History Through Literature Project. University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010.

- The Romantic Appeal of Joseph Campbeler