The Indian Princess (play)

The Indian Princess; or, La Belle Sauvage, is a musical play with a libretto by James Nelson Barker and music by John Bray, based on the Pocahontas story as originally recorded in John Smith's The Generall Historie of Virginia (1621). The piece is structured in the style of a Ballad-opera, with songs and choruses, and also has music underlying dialogue, like a melodrama. Pocahontas persuades her father, King Powhatan, to free Smith and becomes attracted to John Rolfe, breaking off her arranged marriage with a neighboring tribal prince, an action that leads to war. Her tribe wins the war, but her father loses trust in the white settlers; Pocahontas warns the settlers who reconcile with Powhatan. Several comic romances end happily, and Smith predicts a great future for the new country.

| The Indian Princess; or, La Belle Sauvage | |

|---|---|

Title page from original 1808 publication of score | |

| Written by | James Nelson Barker |

| Date premiered | April 6, 1808 |

| Place premiered | The Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia |

| Original language | English |

The play deals with relations between Native Americans and the first European settlers in America. Scholars have debated whether the piece is progressive in its depiction of the natives and have commented that the work reflects an emerging American dramatic and musical sensibility. It served to popularize and romanticize the Pocahontas story as an important American myth.

The comedy was first performed in 1808 at The Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia. It has been cited as the first play about American Indians by an American playwright known to be produced on a professional stage, and possibly the first play produced in America to be then performed in England, although the validity of both statements has been questioned. Its portrayal of Native Americans has been criticized as racially insensitive, but the piece is credited with inspiring a whole new genre of plays about Pocahontas specifically and Native Americans in general, that was prevalent throughout the 19th and early 20th Century. The play was subsequently produced throughout the country.

Background

Barker was motivated to create a truly "American" style of drama to counteract what he saw as "mental colonialism" and the American tendency to feel culturally inferior to Europe.[1] For this reason, he looked to native subject matter for the play, as opposed to other American dramatists like John Howard Payne who neglected American subject matter and locations.[2]

Although in his preface, Barker cites his primary source of inspiration as John Smith's The Generall Historie of Virginia (1624), he was likely more influenced by a series of popular books by John Davis, including, Travels of Four Years and a Half in the United States of America (1803), Captain Smith and Princess Pocahontas (1805), and The First Settlers of Virginia (1806) which featured a more sexualized and romanticized characterization of Pocahontas.[3]

Much of the known background about the piece comes from a letter Barker wrote to William Dunlop, dated June 10, 1832. In it, he indicates that he had been working on The Indian Princess for a number of years before it was first produced in 1808. In fact in 1805, he wrote a Masque entitled "America" (which has not survived) that he intended to serve as a conclusion to the play, in which characters called "America," "Science," and "Liberty" sing and engage in political debate.[4][5] Barker originally intended the piece as a play without music,[6] but John Bray, an actor/translator/composer[2] employed by The New Theatre in Philadelphia, convinced him to add a musical score.[7]

Character list

The published dramatis personæ divides the character list into "Europeans" (the settlers) and "Virginians" (the natives), listing the men first, by rank, followed by the women and the supernumeraries.

Europeans

|

Virginians

|

Plot synopsis

Act I

At the Powhatan River, Smith, Rolfe, Percy, Walter, Larry, Robin, and Alice disembark from a barge as the chorus of soldiers and adventurers sing about the joy of reaching the shore. Larry, Walter, Alice (Walter's wife), and Robin reminisce about love, and Robin admits to Larry his lustful feelings about Alice. Meanwhile, Nima is preparing a bridal gown for Pocahontas in the royal village of Werocomoco, but Pocahontas expresses displeasure about the arrangement her father made for her to marry Miami, a rival Indian prince. Smith is then attacked by a party of Indians, including Nantaquas, Pocahontas's brother. Due to his fighting prowess, Nantaquas thinks he is a god, but Smith explains he is only a trained warrior from across the sea. The Indians capture Smith to bring him to their chief. Back at the Powhatan River, Robin attempts to seduce Alice, but is foiled by Walter and Larry. When Walter tells the group about Smith's capture, they depart to go after him. Before they leave, Rolfe tries to convince Percy to move on after his lover, Geraldine, apparently was unfaithful.

Act II

When King Powhatan is presented with the captured Smith, he decides, at the urging of the tribe's priest Grimosco, to execute him. Pocahontas, having been moved by Smith's nobility, says she will not allow Smith to be killed unless she herself dies with him. This persuades Powhatan to free Smith. Soon, Percy and Rolfe encounter Smith and his Indian allies on the way back to the settlement, and Rolfe is immediately struck by Pocahontas, whose manner suggests the attraction is mutual. They speak of love, but Rolfe must soon depart with Smith. Pocahontas confesses her love for Rolfe to Miami, who receives the news with anger, jealousy and rage. Pocahontas convinces her father to dissolve her arranged engagement with Miami, which will mean war between their two tribes.

Act III

Jamestown has now been built and Walter tells his wife Alice about Powhatan's victory over Miami. They then discuss a banquet hosted by Powhatan that Smith, Rolfe and Percy will attend. Meanwhile, Pocahontas and Nima witness Grimosco and Miami plotting to kill the European settlers. When Grimosco coerces Powhatan into believing he should kill all the White men, by casting doubt about their intentions, creating fear about how they will act in the future, and invoking religious imagery, Pocahontas runs to warn the settlers about the danger. Back in Jamestown, a comic bit ensues in which Larry's wife Kate has arrived disguised as a male page, and teases him before revealing herself. She says she has come with Percy's lover, Geraldine, also disguised as a page, who has come to convince Percy he was wrong about her infidelity. Pocahontas arrives and convinces the settlers to go to Powhatan's palace to rescue their colleagues from Grimosco's plot. They arrive just in time to prevent the disaster. Grimosco is taken away, and Miami stabs himself in shame. Everyone else has a happy ending: Pocahontas is with Rolfe, Walter is with Alice, Larry is with Kate, Percy is with Geraldine, and even Robin is with Nima. Smith forgives Powhatan, and gives the play's final speech, predicting a great future for the new country that will form in this land.[9]

Score

The surviving published version of the musical score appears in the format of a simplified keyboard transcription using a two-staff system (treble and bass). [10] It includes only occasional notations about the instruments used in the original full orchestral score, which has not survived. Therefore, musical elements from the original production such as inner harmonic parts, countermelodies, and accompaniment figurations are no longer known. Based on records of payments made to musicians at The Chestnut Street Theatre at the time of the premiere, it was likely that the production employed approximately 25 pieces, which may have consisted of pairs of woodwinds (flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons) and brasses (horns and trumpets) as well as some timpani and strings. Typically, however, the entire orchestra was used only for the overture and selected large chorus numbers, while solo numbers were accompanied by strings and one or two pairs of woodwinds. The brasses and timpani may have been used to invoke a sense of the military in numbers like Walter's "Captain Smith."[11]

Performances

The play first premiered at The Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia on April 6, 1808.[12] In Barker's letter to Dunlop, he writes the performance was done as a benefit for Mr. Bray (who also played the role of Walter). However, other sources suggest it was a benefit for a Mrs. Woodham.[13] In any case, it is clear that the performance was interrupted by an offstage commotion which may have cut the performance short. Mr. Webster, a tenor who played the role of Larry, was an object of public scorn at the time because of his effeminate manner and dress, and audience members rioted in outrage at his participation, causing Barker himself to order the curtain to be dropped.[13] The play was subsequently performed again in Philadelphia on February 1, 1809, although it was advertised for January 25.[14]

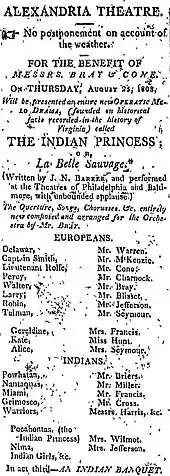

There is some discrepancy about the date of the New York premiere, which took place at The Park Theatre, either on June 14, 1808,[6] or on January 14, 1809, as a benefit for English actress Mrs. Lipman. It was performed again in New York as a benefit for Dunlop on June 23, 1809,[14] There was a performance benefiting Bray and an actor named Mr. Cone advertised for August 25, 1808, at The Alexandria Theatre in Virginia.[15] There was also a gala premiere on an unspecified date in Baltimore.[12] Barker wrote in his letter to Dunlop that the play was subsequently and frequently performed in all the theatres across the country.[6] It was the standard practice in all these productions for the Native American roles to be played by white actors wearing dark makeup.[16]

The Indian Princess has been cited as the first well-documented case of a play that was originally performed in America being subsequently staged in England.[7] Although records indicate there was a play called Pocahontas; or the Indian Princess, credited as being adapted by T.A. Cooper, that played The Theatre Royal at Drury Lane in London on December 15, 1820, and subsequently on December 16 and December 19, the piece differed drastically from Barker's original and featured a completely different cast of characters. Barker himself wrote that the production was done without his permission or even his knowledge, and based on a critical response he read of the London performance, he deduced that there was very little in the play that was his own.[17] Other evidence suggests that the script used in England was not only a completely different play, but that it was likely not even originated by an American. This assertion is based primarily on three factors: the kinder and meeker portrayal of the Natives, which reduces the grandeur of the play's American heroes, the more vague listing of the setting as "North America" rather than specifically "Virginia," and the lack of implications about America's great destiny that was evident in Barker's version.[18] The distinction between the London and American versions is also supported by a review of the London production, in which the reviewer cites a lack of comic characters (Barker's version included several), and the presence of a character named "Opechancaough," who is nowhere to be found in Barker's play. [19]

Style and structure

Structurally, the play resembles a typical English Ballad-opera. [2] The plot of the play can be seen as a blending of a comedy of racial and cultural stereotypes with a love story and an historical drama. Barker borrows heavily from Shakespearean comedy, as can be seen most blatantly in the gender disguises employed by the characters of Kate and Geraldine.[20] The use of verse writing for higher class characters and prose for those of lesser status also borrows from the Shakespearean tradition. It is of note that Pocahontas switches from prose to verse after falling in love with Rolfe.[21]

The Indian Princess is also one of the first American plays to call itself a "melo-drame" (or melodrama) which literally is French for "play with music."[22] Like the French and German melodramas typical of the period, the score contained open-ended snippets of background mood music that can be repeated as much as necessary to heighten the sentimentality of the drama,[2] although some have argued that it bears no other resemblance to the typical French melodrama of the period.[7] Still others have said that the categorization of the piece as a melodrama is accurate, considering the play's portrayal of the genre's typical persecuted heroine (Pocahontas), villainous antagonists (Miami and Grimosco), virtuous hero (Smith), and comic relief (Robin and others).[23]

The play can also be seen as a predecessor to the exaggerated emotionalism of later American drama, and as an early example of how background music would be used in more modern American drama and films.[2]

Analysis and criticism

The Indian Princess is one example of an attempt by an artist of the early 19th Century to define an American national identity. Pocahontas, representing the spirit of America, literally shields Smith from injury and serves as foster mother, protecting colonists from famine and attack, achieving mythic status as a heroic mother, and preserving, nurturing and legitimizing America as a country. The play allows for an acknowledgement of the troubling aspects of the nation's history of conquest, violence, and greed, by couching the negative implications in a romantic plot. In other words, the romantic conquest helps to soften the harshness and brutality of the colonial conquest.[24] The success of the play reflects a larger cultural desire to express its sense of self through the Pocahontas myth.[25]

Barker also had commercial interests, and was motivated by a drive for artistic and financial success. In this vein, the play was an attempt to please the anglophile public, but create something truly American in setting and theme.[26] The portrayals of the Indians in the play, from a perspective of racial sensitivity, have been met with mixed reviews by modern critics. Some write positively about the portrayals, saying that, other than Grimosco and Miami, the natives are noble, though primitive, and have a more "American" value system than the savages traditionally portrayed in British media of the period.[27] Others, however, see the characters portrayed stereotypically as lusty, childlike, weak and corruptible beings, with the exceptions of Pocahontas and Nantaquas, who are portrayed positively only because they accept English values.[28] Still others take a middle ground, noting the range of representations.[16] In any case, the play can be seen as a justification of White assimilation of the natives, especially when examining Pocahontas's choice to be with Rolfe as a microcosm of their societies.[29]

Critics have pointed out several inherent flaws in the script, including the early placement of the play's climax (Smith at the chopping block) at the beginning of Act II,[30] loose construction, [20] song lyrics that trivialize characters,[29] and a main character in Pocahontas that is somewhat stilted and overly poetic.[31] In contrast, however others have argued that Pocahontas's love scene in Act III is where the truest poetry of the piece emerges.[21]

There has been less critique of Bray's musical work, but Victor Fell Yellin tried to recreate what he felt was the score's melodic expressiveness and sonorous grandeur in his 1978 recording of it.[32] In the liner notes, he points out that the music does not critically compare with the great musical masters of its time, but its success is derived from its charm. While it lacks modulation, it contains well-turned melodic and rhythmic phrases, and syncopations that add to its American style.[33]

The Indian Princess certainly began a long American tradition of romanticizing and sexualizing Pocahontas, who was only a child in Smith's original accounts.[20] Therefore, it deserves recognition for inaugurating a genre, but it can be criticized for diminishing the potential richness of the subject matter.[34]

Historical significance

Barker's The Indian Princess has been cited as the first American play featuring Native American characters to ever be staged,[7][35] although Barker's play is predated by at least two offerings by Europeans featuring Native Americans, including Tammany in 1794 by British playwright Ann Kemble Hatton,[23] and German writer Johann Wilhelm Rose's Pocahontas: Schauspiel mit Gesang, in fünf Akten (A Play with Songs, in five Acts) in 1784.[36] At least one American play was also written before Barker's: Ponteach, published by Robert Rogers in 1766, though the piece was apparently never produced.[7] However, more recently uncovered evidence shows a record of an anonymous melodrama entitled Captain Smith and the Princess Pocahontas produced at The Chestnut Street Theatre in 1806, calling into question whether Barker's play was really the first of its kind (though no further information is known about the earlier piece).[37] Barker's play has also been cited as the earliest surviving dramatized account of Smith and Pocahontas,[2] although this idea is debunked by the availability of the aforementioned Johann Wilhelm Rose work.[38]

In any case, The Indian Princess is credited as being primarily responsible for elevating the Pocahontas story to one of the nation's most celebrated myths,[37] and is thought to mark the beginning of the popular American genre of Indian Drama.[39] The piece is also of note as one of very few of its time to have the entire musical score published and available today, as opposed to only individual popular songs.[2]

.jpg.webp)

Barker's play directly or indirectly inspired many other stage adaptations of the Pocahontas story, including:

- Pocahontas, or the Settlers of Virginia by George Washington Parke Custis (1830)[39]

- Pocahontas by Robert Dale Owen (1837)[39]

- The Forest Princess by Charlotte B. Conner (1848)[39]

- Po-ca-hon-tas, or The Gentle Savage by John Brougham (1855)[40]

- Pocahontas by Welland Hendrick (1886)[41]

- Pocahontas by Edwin O. Ropp (1906)[41]

- Royalty in Old Virginia by Effie Koogle (1908)[42]

- Pokey; Or, The Beautiful Legend on the Amorous Indian by Phillip Moeller (1918)[42]

- Pocahontas and the Elders by Virgil Geddes (1933)[42]

- The Founders by Paul Green (1957)[42]

Additionally, there were approximately 40 plays with Indian themes recorded from 1825 to 1860 that likely were directly influenced by The Indian Princess.[14] Edward Henry Corbould's engraving (c. 1850), "Smith Rescued by Pocahontas" was possibly also directly inspired by The Indian Princess.[43] Disney's animated Pocahontas (1995) is one of the more recent of several films also in the same tradition as Barker's play.[25]

Notes

- Bak 2008, p. 178.

- Hitchcock 1972, p. Introduction.

- Abrams 1999, p. 56-58.

- Moses 1918, p. 567.

- Musser 2017, pp. 13–14.

- Moses 1918, p. 570.

- Quinn 1979, p. 139.

- Barker 1808, p. 6.

- Barker 1808, p. 7-74.

- Bray 1808, p. 3-42.

- Yellin 1978, p. 2–4.

- Hitchcock 1955, p. 376.

- Yellin 1978, p. 4.

- Musser 2017, p. 23.

- Alexandria Daily Gazette 1808, p. 3.

- Richards 1997, p. xxxiii.

- Musser 2017, pp. 23–25.

- Earnhart 1959, p. 326-329.

- The Times 1820, p. 3.

- Richards 1997, p. 110.

- Quinn 1979, p. 140.

- Richards 1997, p. xv.

- Hitchcock 1955, p. 378.

- Scheckel 2005, pp. 231–243.

- Richards 1997, p. xxxv.

- Bak 2008, p. 190.

- Bak 2008, p. 179.

- Abrams 1999, p. 59.

- Richards 1997, p. 111.

- Hitchcock 1955, p. 383.

- Musser 2017, p. 20.

- Yellin 1978, p. 2.

- Yellin 1978, p. 5.

- Richards 1997, p. 112.

- Vickers 2002, p. 215.

- Mossiker 1996, p. 325.

- Bak 2008, p. 175.

- Digitale Bibliothek 2013.

- Musser 2017, p. 22.

- Musser 2017, p. 22-23.

- Mossiker 1996, p. 326.

- Mossiker 1996, p. 327.

- Abrams 1999, p. 62.

References

- Abrams, Ann Uhry (1999). The Pilgrims and Pocahontas : rival myths of American origin. Boulder, Colo. [u.a.]: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813334974.

- "Alexandria Theatre Advertisement". Alexandria Daily Gazette. Alexandria, VA. 24 August 1808. p. 3.

- Barker, J.N. (1808). The Indian Princess; or, La Belle Sauvage. Philadelphia: G.E. Blake.

- Bak, J. S. (2008). "James Nelson Barker's The Indian Princess: The role of the operatic melodrama in the establishment of an American belles-lettres". Studies in Musical Theatre. 2 (2): 175–193. doi:10.1386/smt.2.2.175_1.

- Bray, John (1808). The Indian Princess or La Belle Sauvage: Musical Score. Philadelphia: G.E. Blake.

- Earnhart, Phyllis H. (1959). "The First American Play in England?". American Literature. Duke University Press. 31 (3): 326–329.

- "Digitale Bibliothek". Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Hitchcock, H. Wiley (1955). "An Early American Melodrama: The Indian Princess of J. N. Barker and John Bray". Notes. 12 (3): 375–388. doi:10.2307/893133. JSTOR 893133.

- Hitchcock, music by John Bray ; text by James Nelson Barker ; new introduction by H. Wiley (1972). The Indian princess : or, La belle sauvage : an operatic melo-drame in three acts ([Partitur] ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306773112.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moses, Montrose Joseph (1918). Representative Plays by American Dramatists. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company.

- Mossiker, Frances (1996) [1976]. Pocahontas: The Life and the Legend (1st Da Capo Press ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306806995.

- Musser, Paul H. (2017) [1929]. James Nelson Barker, 1754-1858, With a Reprint of his Comedy: Tears and Smiles. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781512818208.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1979). A history of the American drama, from the beginning to the Civil War (1st Irvington ed.). New York: Irvington Publishers. ISBN 978-0891972181.

- "Review of Drury-Lane Theatre's Pocahontas or, The Indian Princess". The Times. London. 16 December 1820. p. 3.

- Richards, Jeffrey H., ed. (1997). Early American drama. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140435887.

- Scheckel, Susan (2005). "Domesticating the drama of conquest: Barker's Pocahontas on the popular stage". ATQ. University of Rhode Island. 10: 231–243.

- Vickers, Anita (2002). The New Nation. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313312649.

- Yellin, Victor Fell (1978). "Two early American musical plays". The Indian Princess/ The Ethiop (PDF) (Liner notes). Taylor, Raynor and John Bray. New York: New World Records. 80232. Retrieved 5 April 2013.