Les Amants du Pont-Neuf

Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (French pronunciation: [lez‿amɑ̃ dy pɔ̃ nœf]) is a 1991 French film directed by Leos Carax, starring Juliette Binoche and Denis Lavant. The film follows a love story between two young vagrants: Alex, a would-be circus performer addicted to alcohol and sedatives, and Michele, a painter with a disease that is slowly turning her blind. The streets, skies and waterways of Paris are used as a backdrop for the story in a series of set-pieces set during the French Bicentennial celebrations in 1989.

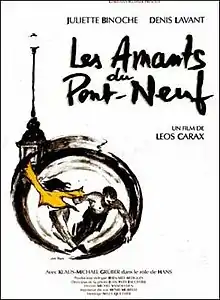

| Les Amants du Pont-Neuf | |

|---|---|

Film Poster, ©Gaumont 1991 | |

| Directed by | Leos Carax |

| Written by | Leos Carax |

| Produced by | Christian Fechner |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jean-Yves Escoffier |

| Edited by | Nelly Quettier |

| Music by | Les Rita Mitsouko David Bowie Arvo Pärt |

| Distributed by | Gaumont |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

The film became notorious for its troubled and lengthy production and for the amount of money it was reported to have cost. It has been referred to several times as the most expensive French film ever made at the time of its release, although this has been contested.

The title refers to the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris. For various reasons, the film-makers ultimately built a scale replica of the bridge, which greatly increased the budget. Though it was released under its original title in other English-speaking territories, the North American title of the film is The Lovers on the Bridge,[1][2] and, in a mistranslation of the original title, the Australian title is Lovers on the Ninth Bridge (instead of "Lovers on the New Bridge").[3][lower-alpha 1]

Plot

Set around the Pont Neuf, Paris's oldest bridge, while it was closed for repairs, Les Amants du Pont-Neuf depicts a love story between two young vagrants, Alex (Denis Lavant) and Michèle (Juliette Binoche). Alex is a street performer addicted to alcohol and sedatives; he scrapes together money by fire breathing and performing acrobatics (sometimes simultaneously). Michèle is a painter driven to a life on the streets because of a failed relationship and a disease which is slowly destroying her sight. Accompanied in her new environment only by a cat, she has grown up in a military family but is passionate about art and longs to see Rembrandt's self-portrait in the Louvre before her vision disappears entirely.

The pair's paths first cross when Alex has passed out, drunk, on the Boulevard de Sébastopol and Michèle makes a sketch of him. Later she is dazzled by one of his street exhibitions and the two become an item. The film portrays their harsh existence living on the bridge with Hans (Klaus Michael Grüber), an older vagrant. Hans is initially hostile to Michèle, but he has secret reasons for this. When he warms to her, he uses his former life to help her realise her dream. The capital's festivities for the 1989 bicentennial of the French Revolution happen in the background to the story: while the skies of Paris are lit up with an extravagant fireworks display, Alex steals a speedboat and takes Michèle water-skiing on the Seine.

Alex's love for Michèle proves to have a dark side, however. As her vision deteriorates, she becomes increasingly dependent on him. When a possible treatment for her condition becomes available, Michèle's family use street posters and radio appeals to trace her. Fearing that she will leave him if she receives the treatment, Alex tries to keep Michèle from becoming aware of her family's attempts to find her by burning the posters; but he also sets fire to the van of the bill-sticker putting them up, and the man is killed. The pair are separated when Alex goes to jail and Michèle has surgery; then, after his release, they meet up on the bridge for a last time. Alex's love for her is unchanged but Michèle has doubts and, enraged, Alex hurls both of them into the Seine. Underwater, they gaze at each other with new eyes in a moment of connection. A westbound barge picks them up, taking the pair onwards to the Atlantic and a new life.

Production

When he started planning it in 1987, Leos Carax wanted to make a simple film, originally intending to shoot in black and white and via Super 8.[6][7][8] His first feature Boy Meets Girl had been a small affair (costing 3 million francs), whereas Mauvais Sang had been considerably larger and more costly (at 17 million),[6][9] albeit more successful at the box office.

From the beginning, shooting a movie on a public bridge in the centre of Paris was complicated.[10] The production team wanted to block off the bridge for three months, but the application was rejected.[8] Instead, a model was created by the set designer Michel Vandestein.[6][11] Initially, the intention was to film the daylight scenes on the actual bridge, and the night-time scenes on the simplified model.[12][13] At this point, the budget was estimated at 32 million francs.[6][14][15][12][13][lower-alpha 2] After scouting in Orléans and the Paris area for locations to build the set, the film-makers settled on the town of Lansargues, in the department of Hérault in southern France.[9] Construction began in August 1988.[16]

The mayor and police of Paris had authorised filming on the actual Pont Neuf for a three-week period ending 15 August 1988 (renovation work was to begin on 16 August, so the permit could not be extended).[9][17][8] During rehearsals, lead actor Denis Lavant injured the tendon in his thumb so badly that filming could not be completed in the given time.[6][9][17] The insurers were called, and Carax was pressured to recast the male lead. The director insisted, however, that he could not recast or change his approach to the film to allow for Lavant's injury. The solution decided on was to extend the Lansargues model for daytime use.[6][9]

The producers secured a further 9 million francs to develop the set. This extra budget seemed too low given the extent of work required at the Lansargues site. It soon became obvious that more money would be required before shooting could resume. Without this funding the producers were obliged to accept an insurance payment that would settle outstanding debts but not allow any further work. In December 1988, production shut down:[6][18] at this point 14 minutes of footage had been shot.[6][14][15][9] In this interim period, Carax circulated videocassettes of the completed footage to drum up interest, and received praise from film-makers such as Steven Spielberg and Patrice Chéreau, who encouraged him to continue.[9][13] In June 1989, Dominique Vignet, together with the Swiss millionaire Francis von Buren, agreed to invest 30 million francs based on the rushes filmed a year before.[9] In July, shooting began again.[6]

It became apparent that this figure, given for the total cost of construction and to finish the film, was not nearly enough; the final number at this stage would be closer to 70 million francs.[16] Von Buren withdrew his funding late in 1989 with an estimated loss of 18 million francs.[6][12][19] Yet again, production stopped. From October 1989 to June 1990 the only person at the site in Lansargues was the guard; additionally, a number of storms followed over that winter causing massive water damage to the uncompleted set.[14][9]

At the Cannes festival in 1990, Christian Fechner undertook to provide funding in order to finish the film. Unable to find financing partners, he provided his own money, purchasing both rights and debts of the picture.[14][15][9] (In the completed film, "Christian Fechner" is the name of a riverboat that rescues the two protagonists.)[17] It was announced that shooting would recommence on 15 August 1990.[14] Recreating the city's fireworks display for Bastille Day in 1989 was among the factors driving up the cost.[17][20] Filming on the set was completed in December 1990[16] and production finally ceased in March 1991.[9][21][lower-alpha 3]

Estimates of the final budget vary: it has been given as 100, as 160 and as 200 million francs.[12][13][17][23] Carax, promoting the film in Britain in 1992, contested the figures that had been reported in the media, while acknowledging that he did not actually know the film's ultimate cost himself.[22]

Carax and Binoche were a romantic couple at the start of filming, though by the time of release they had split.[12][22][24][20] To prepare for her role, Binoche (like Lavant) rough-slept in the streets of Paris.[7][25][lower-alpha 4] According to Carax, she insisted on performing the dangerous water-skiing scene herself (at one point in filming she nearly drowned);[22][28][29] she also put her career on hold to make herself available during the lengthy production delays, turning down job offers from Robert De Niro, Elia Kazan and Krzysztof Kieślowski.[9][30][12][31][32][33] Binoche was one of the cast and crew members who combined to pay the security guard on the Lansargues site while filming stopped,[16][9] and was personally involved in fundraising, meeting producers, lawyers and the Minister of Culture.[9][34] Carax later remembered that in dispirited periods he sometimes believed the film would never be completed, but that Binoche never wavered.[35][lower-alpha 5]

The film was the subject of two documentaries: Enquête sur un film au-dessus de tout soupçon by Olivier Guiton and Le Pont-Neuf des amants by Laurent Canches (both 1991).[36][37]

Release

The film premiered at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival[8] before arriving in French theatres on 16 October 1991.[34][38] The film had 867 197 admissions in France where it was the 34th highest earning film of 1991.[39] 260,000 of the tickets sold were in Paris alone.[21]

Reception

The film divided critical opinion in France. In the popular press, while L'Express responded dismissively ("One hundred and sixty-million francs, and for what? One bridge, three tramps and a cat"), Le Monde was enthusiastic ("a film whose form, more than its content, oozes an emotion as pure and immediate as the unforgettable pre-war melodramas"),[17] as was Le Point ("magical, mad, uncompromising, like its creator... an artistic miracle").[lower-alpha 6] Among film journals, Marc Esposito in Studio made wounding comments about the film and Carax personally,[38] as did La Revue du Cinéma,[40] but the reaction among what Stuart Klawans calls "auteurist critics" was warmer: Positif was favourable, and Cahiers du Cinéma devoted an entire issue to the movie.[20][30][41] A factor in the critical hostility was the amount of money allegedly spent:[22][20] media sources repeatedly claimed that it was the most expensive film in French history,[lower-alpha 7] though Van Gogh (also released in 1991) had a budget roughly equivalent to the 160 million francs mentioned in the media.[31][lower-alpha 8]

In order to recoup its costs, Les Amants needed to do well in overseas markets.[20] It opened in Britain in September 1992, and received positive reviews in The Independent and Empire, though perhaps the most enthusiastic was Sight and Sound: "exciting and innovative... one of the most visually exhilarating and surprising films of recent years".[12][50][23][51] When it played at the 1992 New York Film Festival, however, Vincent Canby reviewed the film for The New York Times. He acknowledged the technical achievement of Vandestein's set design, and the power of the fireworks and speedboat sequences, but was cool about the film overall: "one of the most extravagant and delirious follies perpetrated on French soil since Marie-Antoinette played the milkmaid at the Petit Trianon".[11] Klawans, who served on the festival's selection committee, believes that Canby's review affected the film's USA distribution chances;[20][31] David Sterritt suggests that potential American distributors were put off by stories of the troubled production and cost overruns.[8] The film did not go on general release stateside until 1999.[28] Critics have however seen echoes of specific sequences in successful anglophone films released in the interim: in The English Patient (1996), of Binoche being lifted up to see a painting;[31][52] in Titanic (1997), of two lovers embracing at the prow of a boat.[31][41] Klawans concludes that, however few Americans were able to see it, film-makers were studying the movie.[31]

When the film finally went on general release in America, after Martin Scorsese had championed it, Klawans in The Nation saluted it as "one of the most splendidly reckless films ever made".[31][8] CNN.com struck similarly hyperbolic notes: "the sort of multi-leveled exhilaration that can be achieved on film when talented artists bother to give it a go... more flashes of legitimate brilliance than you'll find in a dozen helpings of Armageddon".[28] Richard Corliss in Time praised Binoche and the film's visual style but said that "The plot groans with lower-depths anomie".[53] Roger Ebert was likewise more balanced: "a film both glorious and goofy, inspiring affection and exasperation in nearly equal measure... It is not the masterpiece its defenders claim, nor is it the completely self-indulgent folly described by its critics. It has grand gestures and touching moments of truth, perched precariously on a foundation of horsefeathers."[54]

Notes

- Several critics comment on the bridge's name: "Despite its name, it is the oldest surviving bridge in Paris... it was the first bridge in the city to break with the medieval tradition of constructing a row of houses along each side and marks the first attempts at coordinated city planning";[4] "Despite its name, it is the oldest bridge in Paris, although when it was built (1578-1606) it would have symbolised progress and modernity".[5]

- Jean-Michel Frodon calls this initial budget expensive but not excessive, saying for context that, although the average cost of a French film at this time was 13.5 million francs, 37 films from 1988 were in the 20-50 million bracket.[10]

- To Fechner and Carax's regret, in January 1991 the duck farmer who owned the site had the entire bridge set destroyed.[9][22]

- This was apparently at Carax's insistence.[18][26][27]

- Binoche likewise remembered that she never lost faith ("On avait vraiment envie de finir ce film, c’était un besoin, je n’ai jamais douté qu’on le finirait").[34]

- "Il est magique, fou, absolu, comme son auteur, Léos Carax... c'est ce miracle artistique qu'il faut célébrer aujourd'hui".[7]

- The claim is made in several sources.[38][42][23][43][44][45][2][46] In France there was a political element to this, as some of the budget had been public money, and questions were asked in the French media about the conduct of Minister of Culture Jack Lang and the way that homegrown movies were funded.[15][9][38][47] Hostility had existed from an early stage: Wendy Everett calls the granting of the original 32-million budget "a controversial move that attracted widespread criticism and more than a little jealousy".[13]

- Within a few years, Germinal and The Horseman on the Roof would equal if not exceed its budget.[31][48][49]

References

- The Lovers on the Bridge, DVDBeaver (illustrates the front covers of the North American Region 1 DVD and the British Region 2 DVD)

- Markey, Paul (15 August 2018). "The Films That Made Me: Les Amants du Pont Neuf". RTÉ. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Australian Centre for the Moving Image. "Lovers on the ninth bridge = Les Amants du Pont-Neuf". Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- Hayes, Graeme (1999). "Representation, Masculinity, Nation: The Crises of Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (Carax, 1991)". In Powrie, Phil (ed.). French Cinema in the 1990s: Continuity and Difference. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 199–210. ISBN 0198159587.

- Everett 2006, p. 210.

- Heymann, Danièle (17 March 1990). "Les amants du pont d'or: Un tournage interrompu deux fois, un décor qui n'en finit pas d'être construit, un feuilleton juridico-financier, «Les Amants du Pont Neuf» de Léos Carax est un film à hauts risques mais un film à sauver". Le Monde. pp. 13–14.

- Pascal, Michel (12 October 1991). "Les amants du Pont-Neuf: Pont d'or pour enfant prodige". Le Point (in French). No. 995. pp. 67–68.

- Sterritt, David (2017). "The Lovers on the Bridge". Cineaste. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Mallat, Robert (1 April 1991). "Les amants du Pont-Neuf: L'odyssée d'un film". Le Point (in French). No. 967. pp. 58–64.

- Frodon 1995, p. 789.

- Canby, Vincent (6 October 1992). "Lovers on the Streets of Paris, Literally". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Thompson, David (September 1992). "Once Upon a Time in Paris: David Thompson considers Leos Carax's extravagant 'Les amants du Pont Neuf'". Sight and Sound. pp. 6–11.

- Everett 2006, p. 209.

- Heymann, Danièle (27 June 1990). "Les amants du Pont Neuf sauvés: Après un feuilleton juridico-financier, Christian Fechner a décidé de reprendre le film de Léos Carax". Le Monde. p. 12.

- Toubiana, Serge (July 1990). "Éditorial: Le pari du Pont-Neuf". Cahiers du Cinéma (in French). No. 434. pp. 14–15.

- Royer, Isabelle (1999). "L'escalade de l'engagement: décideurs et responsabilité. Étude du cas 'Les Amants du Pont Neuf'". In Ingham, Marc; Koenig, Gérard (eds.). Perspectives en Management Stratégique. Caen: Éditions Management et Sociétés. pp. 89–110.

- Gumbel, Andrew (15 November 1991). "So Beautiful and Costly". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Ostria, Vincent (October 1991). "Entretien avec Denis Lavant". Cahiers du Cinéma (in French). No. 448. pp. 18–20.

- Frodon 1995, p. 790.

- Klawans, Stuart (1999). Film Follies: The Cinema Out of Order. London; New York: Cassell. pp. 171–73. ISBN 0304700533.

- Frodon 1995, p. 792.

- Johnston, Sheila (3 September 1992). "Underneath the arches: Director Leos Carax recreated the centre of Paris in the middle of a field in the South of France for Les Amants du Pont Neuf. Sheila Johnston met him". The Independent. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Bloom, Phillipa (1 January 2000). "Les Amants du Pont-Neuf Review". Empire. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Waxman, Sharon (27 February 1994). "Juliette Binoche: Bonjour Tristesse? Her films are sad, but for the French actress, real life is much sunnier". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- Barnett, Laura (31 July 2011). "Being Juliette Binoche". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Everett 2006, p. 207.

- Grater, Tom (9 December 2019). "Juliette Binoche Talks Working With Godard, Kieslowski, Denis, Carax & More – Macao". Deadline. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- Tatara, Paul (30 July 1999). "Grunge and fireworks in 'Lovers on the Bridge'". CNN.com. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- Adams, Tim (11 June 2017). "Juliette Binoche: 'Life is to love'". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- Bourguignon, Thomas (November 1991). "L'amour en Seine: Les Amants du Pont-Neuf". Positif (in French). No. 369. pp. 37–38.

- Klawans, Stuart (1 July 1999). "Bridge Over Troubled Water". The Nation. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- Vincendeau 2000, p. 244.

- Médioni, Gilles (29 July 2020). "Au-delà de la mer Egée, la tragédie grecque d'Elia Kazan". Paris Match. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- Toubiana, Serge (May 1991). "Entretien avec Juliette Binoche: La croix et la foi". Cahiers du Cinéma (in French). No. 443. pp. 36–40.

- Fevret, Christian; Kaganski, Serge (December 1991). "Leos Carax: à l'impossible, on est tenu". Les Inrockuptibles (in French). No. 32. pp. 90–99. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- Daly & Dowd 2003, p. 178.

- Pichon, Alban (2009). Le cinéma de Leos Carax: L’experience du déjà-vu (in French). Latresne: Bord de l'eau. p. 14. ISBN 9782356870247.

- Esposito, Marc (November 1991). "Les amants et le robot". Studio (in French). No. 55. pp. 61–62. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- JP (16 October 1991). "Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (1991)". JPBox-Office. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Zimmer, Jacques (October 1991). "Les amants du Pont-Neuf: Histoire de l'œil". La Revue du Cinéma (in French). No. 475. pp. 21–22. Zimmer calls Carax neurotic and narcissistic (névrotique and narcissique) and describes the affectations (afféteries) that characterise his style. Esposito tempered his criticisms of Carax's perceived failures as an individual with recognition of his talent, and compared Les Amants unfavourably to Mauvais Sang: Zimmer did not do this.

- Baumgarten, Marjorie (26 November 1999). "The Lovers on the Bridge". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Riding, Alan (20 December 1992). "Juliette Binoche Plays a Riddle Without a Solution". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- Tobias, Scott (19 April 2002). "Lovers on the Bridge". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- Austin 2008, p. 133.

- Gibbs, Ed (19 August 2012). "Pardon the French". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Chen, Nick (7 July 2021). "A beginner's guide to Leos Carax in eight YouTube videos". Dazed Digital. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- Frodon 1995, pp. 789, 790–91.

- Austin 2008, p. 166.

- Vincendeau 2000, p. 242.

- Johnston, Sheila (10 September 1992). "Throwing sand in your eyes". The Independent. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- Vincendeau, Ginette (September 1992). "Les amants du Pont-Neuf". Sight and Sound. pp. 46–47.

- Vincendeau 2000, p. 248.

- Corliss, Richard (5 July 1999). "Short Takes: The Lovers on the Bridge Directed by Leos Carax". Time. No. 154. p. 84.

- Ebert, Roger (3 November 1999). "The Lovers on the Bridge". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 13 August 2023 – via RogerEbert.com.

Sources

- Austin, Guy (2008). Contemporary French Cinema: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4611-7.

- Daly, Fergus; Dowd, Garin (2003). Leos Carax. Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9781526141590.

- Everett, Wendy (2006). "Les Amants du Pont-Neuf / The Lovers of Pont-Neuf". In Powrie, Phil (ed.). The Cinema of France. London: Wallflower. pp. 207–215. ISBN 1-904764-46-0.

- Frodon, Jean-Michel (1995). L'âge moderne du cinéma français: De la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours. Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 208067112X.

- Vincendeau, Ginette (2000). Stars and Stardom in French Cinema. London; New York: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-4731-7.