Malazan Book of the Fallen

Malazan Book of the Fallen /məˈlæzən/[1] is a series of epic fantasy novels written by the Canadian author Steven Erikson. The series, published by Bantam Books in the U.K. and Tor Books in the U.S., consists of ten volumes, beginning with Gardens of the Moon (1999) and concluding with The Crippled God (2011). Erikson's series is extremely complex with a wide scope, and presents the narratives of a large cast of characters spanning thousands of years across multiple continents.[2][3][4][5]

Ebook cover of the series | |

| Author | Steven Erikson |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | High fantasy |

| Publisher | Tor Books (US) Bantam Press (UK) Subterranean Press (Limited Edition) |

| Published | 1 April 1999 – 21 February 2011 |

| Media type | Print Digital |

| No. of books | 10 |

| Followed by | |

His plotting presents a complicated series of events in the world upon which the Malazan Empire is located. Each of the first five novels is relatively self-contained, in that each resolves its respective primary conflict; but many underlying characters and events are interwoven throughout the works of the series, binding it together. The Malazan world was co-created by Steven Erikson and Ian Cameron Esslemont in the early 1980s as a backdrop to their GURPS roleplaying campaign.[6] In 2005, Esslemont began publishing his own series of six novels set in the same world, beginning with Night of Knives. Although Esslemont's books are published under a different series title – Novels of the Malazan Empire – Esslemont and Erikson collaborated on the storyline for the entire sixteen-book project and Esslemont's novels are considered to be as canonical and integral to the series' mythos as Erikson's own.

The series has received widespread critical acclaim, with reviewers praising the epic scope, plot complexity and characterizations, and fellow authors such as Glen Cook (The Black Company) and Stephen R. Donaldson (The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant) hailing it as a masterwork of the imagination, and comparing Erikson to the likes of Joseph Conrad, Henry James, William Faulkner, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.[7][8][9]

Setting

| Malazan World | |

|---|---|

| Malazan: Book of the Fallen location | |

Fan-made map of the Malazan world. | |

| First appearance | Gardens of the Moon |

| Last appearance | Kellanved’s Reach |

| Created by | Steven Erikson |

| Genre | fantasy |

The Malazan world has no official unified name, although Steven Erikson has jokingly called it Wu.[10] The name has gained traction among fans as an affectionate and informal term for the planet.

The Malazan world is a globe[11] and appears to be similar in size to Earth, and may be notably larger. No unified map of the entire planet has been published to date, although fans have frequently attempted to create one. According to Erikson, a world map may appear in the planned Encyclopaedia Malazica. He has also confirmed that rough sketches of such maps have already been created.

In an interview with a Spanish fantasy blog, Erikson said that the hand-drawn version of the Malazan world which he had at home was too large to be photocopied; however, he also said that the maps created by fans were coming close.[12]

The Malazan planet has at least four moons, although only one is easily visible from the surface and known to the general population. Three other moons are perpetually occluded from the sun's light. Early historical texts suggested they were not always so difficult to see.[13] Constellations visible from the world included the Roads of the Abyss and the Dagger.[14][15]

Geography

There are at least six continents on the Malazan world according to Midnight Tides.[16] However, Return of the Crimson Guard suggests twelve major landmasses exist.[17] The definition of what constitutes a "continent", "subcontinent" or large island in the world has never been firmly defined.

The largest continent on the Malazan world has no overall name. This landmass's eastern region (comprising roughly one-third of the entire landmass) is known as Seven Cities. This region is separated from the rest of the landmass by the vast Jhag Odhan. To the west of this lies the kingdoms of Nemil and Perish, whilst to the south-west lies the substantial Shal-Morzinn Empire.

South of Seven Cities lies the Falari Isles and the small continent of Quon Tali. Quon Tali is the heartland of the Malazan Empire, which was born on an island just off its southern coast. The island of Drift Avalii is located some distance off its south-western coast.

The narrow Strait of Storms divides Malaz Island from the continent of Korelri. Korelri is a large landmass comprising two subcontinents, Fist and Stratem. Fist consists of a vast number of islands and a part of the adjacent landmass. The Aurgatt Range divides the lands of Fist from Stratem.[18] Stratem consists of several peninsulas, divided from one another by a large inlet known as the Sea of Chimes.

South-west of Korelri and Quon Tali, beyond a vast field of floating ice, lies the small island-continent of Jacuruku. Jacuruku is a land of harsh extremes, with burning deserts on the western side and verdant jungle on the eastern.

East of Seven Cities and north-east of Quon Tali, across Seeker's Deep, lies the continent of Genabackis. Genabackis is a narrow but long continent stretching for many hundreds of leagues from north to south. To the east of Genabackis lies the Genostel Archipelago, comprising one large island (itself large enough to be counted as a subcontinent) and many smaller ones. Further east still is the Cabal Archipelago, which may lie closer to the far western coast of Seven Cities.

Due east of Quon Tali and south-east of Genabackis lies the continent of Assail. This is a long landmass comprising two distinct regions, Assail proper (which is regarded as a land of unrelenting hostility) and a more civilised peninsula area in the south, known as Bael.

East of Assail, south of western Seven Cities and south-west of Jacuruku, lies the large continent of Lether, named for its largest nation. Isolated from the rest of the world by distance and the immense ice fields near Jacuruku, Lether had little contact with other lands and nations prior to the arrival of the renegade Malazan 14th Army.

Books

The Kharkanas Trilogy

The Kharkanas Trilogy is a prequel series written by Steven Erikson after the completion of the main series. The series deals with the Tiste before their split into darkness, light and shadow. It sheds light on the events that are often hinted at in the background of Malazan Book of the Fallen. Many of the important Tiste characters from the Malazan Book of the Fallen make an appearance like Anomander Rake, Draconus, Spinnock Durav and Andarist.

| Title | Published | Approximate Word Count | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forge of Darkness | 2 August 2012 | 292,000 | 688 |

| Fall of Light | 26 April 2016[19] | 363,000 | 864 |

| Walk in Shadow | In Progress | n/a | n/a |

| Approximate Total: | 655,000 | 1,552 | |

Path to Ascendancy

The Path to Ascendancy is a prequel series set in the world of Malazan, written by Ian Cameron Esslemont.[20] The stories deal with the early adventures of Dancer and Kellanved (Dorin and Wu, in this series) and their eventual rise to power on Quon Tali.

| Title | Published | Approximate Word Count | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dancer's Lament | 25 February 2016 (UK), 31 May 2016 (US)[21] | 145,000 | 592 |

| Deadhouse Landing[22] | 15 November 2017 | 136,000 | 400 |

| Kellanved's Reach[23] | 19 February 2019 | 112,000 | 592 |

| Forge of the High Mage | 6 April 2023 | 152,000 | 480 |

| Approximate Total: | 545,000 | 2,064 | |

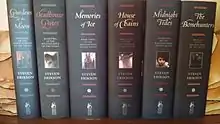

Malazan Book of the Fallen

The main series written by Steven Erikson. The first book in the series, Gardens of the Moon, was shortlisted for a World Fantasy Award. The second novel, Deadhouse Gates, was voted one of the ten best fantasy novels of 2000 by SF Site.[24] See the structure section below for more information.

| # | Title | 1st Publication | Approximate Word Count[25] | Pages (Tor Books Trade Paperback)[26][27] | Pages (Bantam Press Mass Market Paperback) | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gardens of the Moon | 1 April 1999 | 209,000 | 496 | 768 | 26h 8m |

| 2 | Deadhouse Gates | 1 September 2000 | 272,000 | 604 | 960 | 34h 5m |

| 3 | Memories of Ice | 6 December 2001 | 358,000 | 780 | 1187 | 43h 59m |

| 4 | House of Chains | 2 December 2002 | 306,000 | 672 | 1040 | 35h 6m |

| 5 | Midnight Tides | 1 March 2004 | 270,000 | 624 | 960 | 31h 3m |

| 6 | The Bonehunters | 1 March 2006 | 365,000 | 800 | 1232 | 42h 6m |

| 7 | Reaper's Gale | 7 May 2007 | 386,000 | 832 | 1280 | 43h 58m |

| 8 | Toll the Hounds | 30 June 2008 | 392,000 | 832 | 1296 | 44h 9m |

| 9 | Dust of Dreams | 18 August 2009 | 382,000 | 816 | 1280 | 43h 13m |

| 10 | The Crippled God | 15 February 2011 | 385,000 | 928 | 1200 | 45h 21m |

| Approximate Total: | 3,325,000 | 7,384 | 11,216 | 16d 5h 8m | ||

Novels of the Malazan Empire

Six-part novel series set in the world of Malazan. It was written by Ian Cameron Esslemont. The novels cover events simultaneous with the Book of the Fallen, like the mystery of the Crimson Guard, the succession of the Malazan Empire, the situation on Korel and Jacuruku and the mystery of Assail. Some of these events are hinted at during the course of the Malazan Book of the Fallen. Characters that appear throughout the novels are Kyle, Greymane and the avowed members of the Crimson Guard like Shimmer, Blues, K'azz, Skinner and Cowl.

| Title | Published | Approximate Word Count | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Night of Knives | 1 September 2004 | 104,000 | 304 |

| Return of the Crimson Guard | 15 August 2008 | 272,000 | 702 |

| Stonewielder | 25 November 2010 | 198,000 | 634 |

| Orb Sceptre Throne | 20 February 2012 | 188,000 | 605 |

| Blood and Bone | 22 November 2012 | 183,000 | 586 |

| Assail | 5 August 2014 | 168,000 | 544 |

| Approximate Total: | 1,120,000 | 3,375 | |

The Witness Trilogy

Planned trilogy written by Steven Erikson. It will be a sequel to the main series featuring Karsa Orlong and his quest to destroy civilization.

| Title | Published on | Approximate Word Count | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| The God is Not Willing | 1 July 2021[28] | 191,000 | 688 |

| No Life Forsaken[29] | Forthcoming | n/a | n/a |

The Tales of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach (novellas)

The first three novellas were published together as The Tales of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach, Volume 1. The Tales of Bauchelain and Korbal Broach, Volume 2 includes the second three novellas.

- Blood Follows (2002)

- The Healthy Dead (2004)

- The Lees of Laughter's End (2007)

- Crack'd Pot Trail (2009)

- The Wurms of Blearmouth (2012)

- The Fiends of Nightmaria (2016)

- Upon a Dark of Evil Overlords (2020)

Reading order

Erikson and Esslemont recommend reading the books in order of publication.[30] Tor.com published a reading order based on the approximate chronological order of events in the series,[31] which the authors did not consider suitable as a reading order for a first-time reader.[30] The publication order of the series is as follows:

Authorship

Conception

The Malazan world was originally created by Steven Erikson and Ian Cameron Esslemont in 1982 as a backdrop for role-playing games using a modified version of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.[32] By 1986, when the GURPS system had been adopted by Erikson and Esslemont,[6] the world had become much larger and more complex, approaching its current scope. It was then developed into a movie script entitled Gardens of the Moon. When this was not successful in finding interest, the two writers agreed to each write a series set in their shared world.[32] Steven Erikson wrote Gardens of the Moon as a novel in the period 1991-92 but it was not published until 1999. In the meantime, he wrote several non-fantasy novels. When he sold Gardens of the Moon, he agreed to a contract for an additional nine volumes in the series. The contract with Bantam UK was worth £675,000 [33] making it "among the largest fees ever paid for a fantasy series".[34]

Ian Cameron Esslemont's first published Malazan story, the novel Night of Knives, was released as a limited edition by PS Publishing in 2004 and as a mass-market hardcover by Bantam UK in 2007. The second novel, Return of the Crimson Guard, was published in 2008, with a limited PS Publishing edition preceding the larger-scale Bantam UK release. The third novel, Stonewielder, was released on 11 December 2010 in the UK by Bantam, and 11 May 2011 in the US by TOR. Orb Sceptre Throne and Blood and Bone, the fourth and fifth novels, were both published in 2012, and Assail, the sixth, was published in 2014.

After finishing the two main series, Erikson and Esslemont continued on to further projects in the Malazan universe. While writing the last novels in The Malazan Book of the Fallen, Erikson decided that his next project, The Kharkanas Trilogy, would be a "trilogy traditional in form," saying the following:

"If the Malazan series emphasized a postmodern critique of the subgenre of epic fantasy, paying subtle homage all the while, the Kharkanas Trilogy subsumes the critical aspects and focuses instead on the homage."[35]

The first novel in the trilogy, Forge of Darkness, was released in 2012, and the second novel, Fall of Light, was released in April 2016. Information on the third novel, Walk in Shadow, is forthcoming. As for Esslemont, the first novel in his Path to Ascendancy trilogy, Dancer's Lament, was released in February 2016.

At one point, Steven Erikson indicated that the two authors would collaborate on The Encyclopedia Malaz, an extensive guide to the series, which was to be published following the last novel in the main sequence.[36] In an interview on a later date, however, he mentioned talks underway with an RPG 20D group to produce a game adapted from the Malazan universe, in which case the maps and notes created by Erikson and Esslemont would be released through installments or expansions rather than through the publishing of an encyclopedia.[37]

Structure

The series is not told in a linear fashion. Instead, several storylines progress simultaneously, with the individual novels moving backwards and forwards between them. As the series progresses, links between these storylines become more readily apparent. During a book signing in November 2005, Steven Erikson confirmed that the Malazan saga consists of three major story arcs, equating them to the points of a triangle.

The first plotline takes place on the continent of Genabackis where armies of the Malazan Empire are battling the native city-states for dominance. An elite Malazan military unit, the Bridgeburners, is the focus for this storyline, although as it proceeds their erstwhile enemies, the Tiste Andii led by Anomander Rake and the mercenaries commanded by Warlord Caladan Brood, also become prominent. The novel Gardens of the Moon depicts an attempt by the Malazans to seize control of the city of Darujhistan. Memories of Ice, the third novel released in the sequence, continues the unresolved plot threads from Gardens of the Moon by having the now-outlawed Malazan armies uniting with their former enemies to confront a new, mutual threat known as the Pannion Domin. Toll the Hounds, the eighth novel in the series, revisits Genabackis some years later as new threats arise to Darujhistan and the Tiste Andii who now control the city of Black Coral.

The second plotline takes place on the subcontinent of Seven Cities and depicts a major native uprising against Malazan rule. This rebellion is known as 'the Whirlwind'. The second novel released in the sequence, Deadhouse Gates, shows the outbreak of this rebellion and focuses on the rebels' relentless pursuit of the main Malazan army as it escorts some 40,000 refugees more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km) across the continent. The story of the pursuit, and the event itself, is referred to as the Chain of Dogs. The fourth novel, House of Chains, sees the continuation of this storyline with newly arrived Malazan reinforcements – the 14th Army – taking the war to the rebels. The 14th's exploits earn them the nickname, 'The Bonehunters'.

The third plotline was introduced with Midnight Tides, the fifth book released in the series. This novel introduces a previously unknown continent where two nations, the united tribes of the Tiste Edur and the Empire of Lether, are engaged in escalating tensions, which culminate in open warfare. The novel takes place contemporaneously with earlier books in the sequence and the events in it are in fact being related in flashback by a character from the fourth volume to one of his comrades (although the novel itself is told in the traditional third-person form).

The sixth book, The Bonehunters, sees all three plot strands combined, with the now-reconciled Malazan army from Genabackis arriving in Seven Cities to aid in the final defeat of the rebellion. At the same time, fleets from the newly proclaimed Letherii Empire are scouring the globe for worthy champions to face their immortal emperor in battle, in the process earning the enmity of elements of the Malazan Empire. The seventh novel, Reaper's Gale, sees the Malazan 14th Army arriving in Lether to take the battle to the Letherii homeland. The ninth and tenth novels, Dust of Dreams and The Crippled God, pick up the storyline on the Lether continent and deal with the activities of the 14th Army following their successful 'liberation' of the Letherii people and the revelation that the K'Chain Che'Malle species and Forkrul Assail species have returned. The 14th Army is attempting to deal with the peril that the Crippled God has caused with his attempts to poison the warrens and to wake Burn.

Ian Cameron Esslemont's novels are labeled as Novels of the Malazan Empire, not as parts of the Malazan Book of the Fallen itself, and deal primarily with the Malazan Empire, its internal politics and characters who only play minor roles in Erikson's novels. His first novel, Night of Knives, details events in Malaz City on the night that the Emperor Kellanved was assassinated. The second, Return of the Crimson Guard, investigates the fall-out in the Malazan Empire from the devastating losses of the Genabackan, Korelri and Seven Cities campaigns following the events of The Bonehunters. Esslemont's third novel, Stonewielder, explores events on the Korelri continent for the first time in the series and focuses on the often-mentioned, rarely seen character of Greymane. The fourth novel, Orb Sceptre Throne, revisits Genebackis once again in the wake of Erikson's Toll the Hounds, and features several well known characters seen in Erikson's novels. Esslemont's fifth novel, Blood and Bone visits the continent of Jacuruku and the sixth, Assail, set on the continent of Assail, serves as a closing chapter and coda for the entire series.

Influences

In a general review of The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature, edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, Erikson fired a shot across the bow of "the state of scholarship in the fantastic as it pertains to epic fantasy,"[38] taking particularly to task James's opening lines in Chapter 5 of that volume. Erikson uses a handful of words from that chapter as an epigraph for a quasi-autobiographical essay in The New York Review of Science Fiction. James's sentences read in full:

"J. R. R. Tolkien said that the phrase 'In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit' came to his unconscious mind while marking examination papers; he wrote it on a blank page in an answer book. From that short sentence, one might claim, much of the modern fantasy genre emerged. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (1954–5) (henceforth LOTR) looms over all the fantasy written in English—and in many other languages—since its publication; most subsequent writers of fantasy are either imitating him or else desperately trying to escape his influence."[39]

Erikson writes, "But epic fantasy has moved on, something critics have failed to notice." He goes on,

"One example of this can be gleaned from my own beginnings as a writer of fantasy, which I suspect was commonplace among my colleagues. In my youth, I sidestepped Tolkien entirely, finding my inspiration and pleasure in the genre through Howard, Burroughs, and Leiber. And as with many of my fellow epic fantasy writers, our first experience of the Tolkien tropes of epic fantasy came not from books, but from Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying games ... As my own gaming experience advanced, it was not long before I abandoned those tropes ... Accordingly, my influences in terms of fiction are post-Tolkien, and they came from conscious responses to Tolkien (Donaldson's Thomas Covenant series) and unconscious responses to Tolkien (Cook's Dread Empire and Black Company series).[38]

Erikson concludes, "So, Professor James, when you say 'since [Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings]... most subsequent writers of fantasy are either imitating him or else desperately trying to escape his influence'—sorry. You're flat-out wrong."

Themes

The Malazan series contains many themes around socio-economic inequality and social injustice throughout such as gender equality with Erikson stating "It occurred to us that it would create a culture without gender bias so there would be no gender-based hierarchies of power. It became a world without sexism and that was very interesting to explore."[40] as well as the inevitability of and role of art in civilizational collapse[41] and many other themes rooted in a postmodernist and post-structuralist deconstruction of the fantasy genre and magical realism.[42][43]

Characters of the Malazan Book of the Fallen

Magic

Magic in the Malazan series is accomplished by tapping the power of a Warren or Hold, from within the body of the mage. Effects common to most warrens include enchantment of objects (investment), minor healing, large-scale blasts and travel through warren across great distances in a short period of time. Other effects are more specific to each warren. For example, Thyr is the warren of light, Telas is the warren of fire, Serc is the warren of Air, and Denul is the warren of healing. The specific uses of this power can vary depending on the ingenuity of the user. Only a minority of humans can access warrens, usually tapping and working with a single one, with High Mages accessing two or three. Two notable exceptions to this are the High Mage Quick Ben who can access seven at any single time out of his repertoire of twelve (due to his killing of and subsequent merging with the souls of eleven other sorcerers), and Beak who can access all the warrens (although he seems to have a cognitive disability). Certain Elder races have access to warrens specific to their race which seem to be significantly more powerful and cannot be blocked by the magic-deadening ore otataral. Examples of this phenomenon are Tellann, representing fire, for the T'lan Imass, and Omtose Phellack, representing ice, for the Jaghut. Further, three aspects of Kurald for each of the Tiste races: Kurald Galain, representing Dark, for the Tiste Andii; Kurald Emurlahn, representing Shadow, for the Tiste Edur; and Kurald Thyrllan, representing Light, for the Tiste Liosan.

Alternatively, a more basic form of magic can be harnessed by using or capturing natural spirits of the land, elements, people, or animals. A form of this method is also utilized when the power of an ascendant or god is called upon or channeled, although in most cases this is also linked with the warren of that being.

Soletaken and D'ivers

Some characters within the Malazan series are able to veer into animal form (shapeshifting). Characters which veer into a single animal are called Soletaken. Examples of Soletaken include Anomander Rake, the Son of Darkness (dragon) and Treach/Trake, a god of war (tiger). D'ivers can veer into a pack of animals. Prominent examples of D'ivers include Gryllen (rats, also known as the Tide of Madness) and Mogora (spiders).

Cards and Tiles

Cards are from the Deck of Dragons while the elder Tiles belong to the Tiles of the Hold. They are similar in that they are used to get information about present and future events. They are used separately on two different continents and both are not known about contiguously except by very rare people such as Bottle, a squad mage in Tavore's 14th Army. Houses (Deck of Dragons) and Holds (Tiles of the Hold) usually relate to Warrens (Deck) and Holds (Tiles). The difference between these two is marked by the progressive evolution of magic. As magic evolves, Tiles and Cards become active or inactive. Usually the two do not overlap, except in a few instances where elder realms have become active (the Beast Hold, mentioned in Memories of Ice and Midnight Tides).

Deck of Dragons

The Deck of Dragons resembles a Tarot card deck in that it consists of cards that divine the future. The difference is that a real Deck of Dragons adjusts itself to the changing circumstances of the pantheon. If an entity ascends or dies, the deck will change to reflect this fact. The pictures on the cards reflect the gods/ascendants that each is made to represent. Not all cards are active on all continents; for example, Obelisk is referred to as inactive on Seven Cities until partway through Deadhouse Gates.

Tiles of the Hold

As an alternative and older version of the Deck of Dragons, the Tiles of the Holds are also used for divination. Their use is restricted to the continent of Lether, where the influence of the Jaghut warren Omtose Phellack halted the evolution of magic in a less developed state. The Tiles of the Hold are cast rather than read.

Critical reception

The series was positively received by critics, who praised the epic scope, plot complexity and the introspective nature of the characterization, which serve as social commentary. Fellow author Glen Cook has called the series a masterwork of the imagination that may be the high water mark of the epic fantasy genre. In his treatise written for The New York Review of Science Fiction, fellow author Stephen R. Donaldson has also praised Erikson for his approach to the fantasy genre, the subversion of classical tropes, the complex characterizations, the social commentary — pointing explicitly to parallels between the fictional Letheras Economy and the US Economy — and has compared him to the likes of Joseph Conrad, Henry James, William Faulkner, and Fyodor Dostoevsky.[44][45][46]

Reviewing for SF Site, Dominic Cilli says, The Malazan Book of the Fallen raises "the bar for fantasy literature", that the world building and the writing are exceptional.[47] Cilli claims the series is written for the "most advanced readers out there.", going on to state that "Even they will have to make two passes through all ten books to fully comprehend the myriad of plotlines, characters and various settings that Erickson presents to us." Reading Erikson's "The Malazan Book of the Fallen" might be "the most challenging literary trial" a reader has ever tried, yet "the payoff is too enormous to ignore and well worth taking on the endeavor. Steven Erikson doesn't spoon feed his readers. He forces you to question and think on a level that very few authors would even dare for fear of finding and perhaps losing an audience."[47]

Footnotes

- Malazan is an adjective meaning "of Malaz" /məˈlæz/. For the pronunciation: Erikson, Steven (28 October 2020). "Steven Erikson Talks Building Malazan, Facebook Post, & MORE!" (Interview). Interviewed by Daniel Greene. YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Bangs, Arthur (14 May 2006). "The Bonehunters by Steven Erikson". SFFWorld.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "What I'm Reading #22 - GARDENS OF THE MOON by Steven Erikson". The Alexandrian. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Steven Erikson's TOLL THE HOUNDS cover art". Pat's Fantasy Hotlist. 16 January 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Floresiensis. "Reviews - Memories of Ice by Steven Erikson". Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Erikson, Steven (2007). "Preface to the Gardens of the Moon redux". Gardens of the Moon. Bantam Books. pp. xii–xiv. ISBN 978-0-553-81957-1.

- "Stephen R. Donaldson: Epic Fantasy: Necessary Literature". The New York Review of Science Fiction. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Episode 264: Glen Cook and Steven Erikson". The Coode Podcast, Discussion and digression on science fiction and fantasy with Gary Wolfe and Jonathan Strahan. 14 January 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Gardens of the Moon by Steven Erikson". macmillan.com. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Q and A with malazanempire No 1 (2003)

- Midnight Tides, Chapter 10, US SFBC p.312

- http://caballerodelarbolsonriente.blogspot.co.uk/2017/12/steven-erikson-no-hay-nada-para.html Interview with El Caballero del Arbol Sonriente, December 2017

- Midnight Tides, Chapter 10, US SFBC p.313

- The Bonehunters, Chapter 3

- Deadhouse Gates, Chapter 17

- Midnight Tides, Chapter 15, US SFBC p.474

- Return of the Crimson Guard, Book 2 Chapter 2

- Return of the Crimson Guard, Book 1 Chapter 4

- "New Malazan Novel Fall of Light Coming April 26". Tor.com. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Dancer's Lament | Ian C. Esslemont | Macmillan". Macmillan. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Erikson, Steven. "Steven Erikson's Reddit AMA reveals New Trilogy titles". Reddit. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Esslemont, Ian (14 April 2016). "Esslemont interview". Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Esslemont, Ian. "Esslemont interview". Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Malazan Book of the Fallen by Steven Erikson". macmillan.com. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Wordcount of popular (and hefty) epics". 27 October 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Malazan Book of the Fallen Series by Steven Erikson". Goodreads. Goodreads, Inc. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- "Malazan Book of the Fallen (10 book series) Paperback Edition". Amazon.com. Amazon.com, Inc. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- . ASIN 1787632865.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Barman, Marc (19 December 2021). "Steven Erikson starts work on sequel to THE GOD IS NOT WILLING".

- "Steven Erikson on the reading order". Reddit.com. 5 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- "The Malazan Authors' Suggested Reading Order for the Series Is Not What You Would Expect". Tor.com. 21 November 2017. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017.

- Introduction to Gardens of the Moon, Special Edition

- Moss, Stephen (14 October 1999). "Malazans and megabucks". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Interview with Steven Erikson in SFX Magazine issue #99, Christmas 2002.

- "An Introduction to Forge of Darkness For Readers Old and New Alike". Tor.com. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Interview: Malazan Book of the Fallen author Steven Erikson | The Void Magazine". the-void.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "Steven Erikson Answers Your Dust of Dreams Questions!". Tor.com. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Erikson, Steven (May 2012). "Not Your Grandmother's Epic Fantasy: A Fantasy Author's Thoughts Upon Reading The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature". The New York Review of Science Fiction. Pleasantville, NY: Dragon Press. 24 (9): 1, 4–5.

- James, Edward (26 January 2012). "Tolkien, Lewis and the explosion of genre fantasy". The Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature. Cambridge Collections Online. ISBN 9780521728737.

- Bandstra, Matt (22 October 2018). "Diversity and Equality Are Foundational Concepts in Malazan Book of the Fallen". Tor.com. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Galaxy, Geek's Guide to the (28 November 2012). "Steven Erikson: I'm Not Competing With George R. R. Martin". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- Canavan, A.P. "Steven Erikson: More Than Meets the Eye". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 29 (1).

- Malazan: A Postmodern Critique of the Fantasy Genre, retrieved 18 March 2021. Archive - "I've waited over twenty years for a postmodern/poststructural analytical discussion of my series. In fact, I'd just about given up hope that these elements would ever be noticed (how many students of philosophy read Epic Fantasy? Well, at least one!). I was lucky in that my initial foray into fiction writing (a Creative Writing program at the University of Victoria) was in the midst of the Magic Realist movement in literature, which as you know is explicitly deconstructed in terms of narrative reliability, while also openly challenging notions of objective reality. Magic Realism of course is deeply connected, philosophically, with Existentialism (made metamorphic beneath tyrannical polities), and all of this led, in a roundabout way, to metafiction. Alas, most metafiction struck me as too obvious, and I remembered wondering, way back then, if there was a way to make metafiction subtle. Then I began to wonder if one could make metafiction a hidden meta-narrative embracing a postmodern, poststructural story. Turns out, the answer is yes, as epitomized in the Malazan Book of the Fallen (the cipher unlocking the metafictional element to the series is found in Toll the Hounds). But for me, all of that was just me grappling with a growing uncertainty regarding almost everything, making the process of writing the series a kind of dialectic, not only between me and myself, but also between realities: ours here on Earth, and that other one being a made-up Malazan world."

- "Stephen R. Donaldson: Epic Fantasy: Necessary Literature". The New York Review of Science Fiction. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Episode 264: Glen Cook and Steven Erikson". The Coode Podcast, Discussion and digression on science fiction and fantasy with Gary Wolfe and Jonathan Strahan. 14 January 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Gardens of the Moon by Steven Erikson". macmillan.com. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Cilli, Dominic (2011). "The Malazan Book of the Fallen". SF Site. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

References

- Moss, Stephen (14 October 1999). "Malazans and megabucks". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Leonard, Andrew (21 June 2004). "Archaeologist of lost worlds". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- Thompson, William (2004). "The SF Site Featured Review: Midnight Tides". The SF Site. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

External links

- Malazan Book of the Fallen series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Malazan Book of the Fallen at the Internet Book List