The Man-Eating Myth

The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy is an influential anthropological study of socially sanctioned "cultural" cannibalism across the world, which casts a critical perspective on the existence of such practices. It was authored by the American anthropologist William Arens of Stony Brook University, New York, and first published by Oxford University Press in 1979.

The first English-language edition of the book | |

| Author | W. Arens |

|---|---|

| Country | United States and United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Cultural anthropology, cannibalism |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

Publication date | 1979 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 206 pp. |

| ISBN | 978-0-19-502793-8 |

Arens' primary hypothesis is that despite claims made by western explorers and anthropologists since the 15th century, there is no firm, substantiable evidence for the socially accepted practice of cannibalism anywhere in the world, at any time in history. Dismissing claims of cultural cannibalism made against the Carib and Aztec peoples by invading Spanish colonialists, he tackles 19th and 20th century claims regarding socially acceptable cannibalism in Sub-Saharan Africa and New Guinea. Turning to prehistory, he critiques archaeological claims to have discovered evidence for such practices in Europe and North America. In the second half of the work, Arens puts forward his argument that an erroneous belief in "others" who commit socially sanctioned cannibalism is a global phenomenon. He proceeds to chastise the anthropological community for perpetuating the "Man-Eating Myth", suggesting reasons as to why they have done so.

The Man-Eating Myth was widely reviewed in academic journals and also attracted attention from mainstream press. Views were mixed, with most reviewers highlighting the intentionally provocative nature of the work. Critics charged Arens with constructing straw man arguments and for exaggerating the methodological problems within anthropology. Though the book was influential and caused a critical re-evaluation of much prior work, its main hypothesis was largely rejected by the academic community.[1][2][3] Increasing archaeological evidence for cannibalism in the decades after the book's publication has made it even less plausible.

Background

William Arens undertook the research for his PhD in Tanzania, Eastern Africa. After beginning his fieldwork in a rural community there in 1968, he discovered that the locals referred to him as mchinja-chinja, a Swahili term meaning "blood-sucker". This was due to a widespread belief in the community that Europeans would collect the blood of Africans whom they killed, convert it into red pills, and consume it. He would note that by the time he left the community a year-and-a-half later, most of the locals still continued to believe this myth.[4]

In the preface to The Man-Eating Myth, Arens notes that he was first inspired to begin a fuller investigation of cannibalism while teaching an introductory course on anthropology at Stony Brook University, New York. One student asked him why he focused his teaching on such topics as kinship, politics and economics rather than the more "exotic" subjects of witchcraft, fieldwork experiences and cannibalism. Arens concurred that these latter topics would interest his students to a greater extent than those which he was then lecturing on, and so undertook an investigation into the prior accounts of cannibalism in the anthropological record.[5]

As he began to read up on the written accounts of cultural cannibalism, he was struck by inconsistencies and other problems in these tales. In search of reliable accounts from anthropologists who had witnessed the practice of cultural cannibalism first-hand, he placed an advertisement in the newsletter of the American Anthropological Association, but again failed to come up with any first-hand documented cases.[6] Prior to its publication, rumors had circulated in the anthropological community that Arens was putting together a book that would challenge the concept of cultural cannibalism.[7]

Synopsis

[T]his essay has a dual purpose. First, to assess critically the instances of and documentation for cannibalism, and second, by examining this material and the theoretical explanations offered, to arrive at some broader understanding of the nature and function of anthropology over the past century. In other words, the question of whether or not people eat each other is taken as interesting but moot. But if the idea that they do is commonly accepted without adequate documentation, then the reason for this state of affairs is an even more intriguing problem.

– William Arens, 1979.[8]

In chapter one, "The Nature of Anthropology and Anthropophagy", Arens discusses the study of anthropophagy, or cannibalism, within the anthropological discipline. Noting that anthropologists have widely taken it for granted that there are societies who socially sanction cannibalism, he nevertheless states that there is no "adequate documentation" for such practices anywhere in the world. In the second part of the chapter, he explores several first-hand accounts of cannibalism and highlights their implausible and inaccurate nature. Beginning with the German Hans Staden's claims to have encountered socially sanctioned cannibalism among the Tupinambá people of South America in the 1550s, Arens illustrates a number of logical contradictions in Staden's account, and highlights the dubious nature of the text. The anthropologist then moved on to the 19th-century accounts of widespread socially approved cannibalism among the Polynesian people of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands provided by Ta'unga, a Polynesian native who had been converted to Christianity and wrote for the London Missionary Society; Arens again highlights a number of inconsistencies and logical impossibilities in Ta'unga's claims.[9]

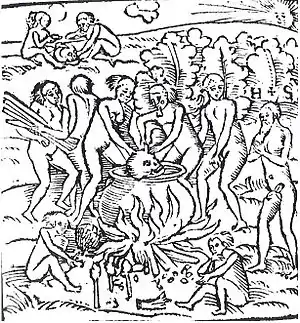

The second chapter, entitled "The Classic Man-Eaters", explores the accounts of cannibalism produced by European colonialists and travellers in the Americas during the Early Modern era. It begins by documenting the Spanish interaction with the Carib people of the Lesser Antilles, first begun by Christopher Columbus and his men in the 1490s. Columbus noted that the Caribs had been described as cannibals by the neighbouring Arawak people of the West Indies, but was initially sceptical about such claims himself. Arens highlights that it was only later, when Columbus began to oversee largescale colonization and pacification of Carib lands, that he began to assert that they were cannibals, in order to legitimize his cause. Arens then proceeds to note that the Spanish government only permitted the enslavement of cannibals in the Caribbean, leading European colonists to increasingly label the indigenous peoples as cannibalistic in order to increase their economic power. Following on from this, Arens goes on to critique the longstanding claims that the Aztec people of Mexico were cannibals; noting that while the early Spanish accounts of the Aztecs include first-hand descriptions of human sacrifice, he highlights that none of these Spanish observers actually witnessed cannibalism, despite the claims that were later made asserting the cannibalistic nature of Aztec religion. In contrast, Arens argues that the Aztecs found the idea of cannibalism – even in survival conditions – socially reprehensible, and believed that some of their neighbouring peoples were guilty of it.[10]

Chapter three, "The Contemporary Man-Eaters" explores the claims made for socially sanctioned cannibalism in the 20th century, with a particular focus on Sub-Saharan Africa and New Guinea. Regarding the former, Arens discusses E. E. Evans-Pritchard's work in disproving that the Azande people were cannibalistic, before arguing that the stories of socially accepted cannibalism in the "Dark Continent" were based largely on misunderstandings and the sensationalist claims of European travellers like Henry Morton Stanley, and that there was no reputable first-hand accounts of such a practice anywhere in Africa. Instead, he notes that many African societies found cannibalism to be a reprehensible anti-social activity that was associated with witchcraft, drawing comparisons with the Early Modern European witch hunt. Moving on to look at claims for cannibalism in New Guinea made by anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Ronald Berndt, he notes that none of them ever actually came across any evidence of the practice themselves, before going on to critique claims that cannibalism was the cause of the kuru outbreak among the New Guinean Fore people in the mid 20th century.[11]

In the fourth chapter, entitled "The Prehistoric World of Anthropophagy", Arens deals with archaeological arguments for socially approved cannibalism in European and North American prehistory. He argues that many early archaeologists, in viewing prehistoric societies as "primitive" and "savage", expected to find widespread evidence of cannibalism within the archaeological record, just as social anthropologists were claiming that the practice was widespread in recently documented "primitive", "savage" societies. He critiques various claims that broken bones represent evidence of cannibalism, both in Iron Age Yorkshire and in the case of Peking Man, maintaining that these breakages could represent many different things rather than cannibalism. He then moves on to look at North American examples, including those from the Pueblo period in the Southwestern United States and among the Iroquois in the country's northeast, in both instances critiquing an interpretation of socially sanctioned cannibalism.[12]

The penultimate chapter, "The Mythical World of Anthropophagy", consists of Arens' argument that all human groups have been accused of socially accepted cannibalism at one point in time, and that these cannibals are often usually thought of as "others", being outside of the accuser's society, and are associated with certain animals because of their "non-human" behaviour. From this, he deduces that the belief in cannibalism is a "universal phenomenon", and questions why this should be so. He suggests that societies gain a sense of self-meaning by conjuring the image of an opposite culture that breaks societal taboos. He also describes the manner in which many societies hold origin myths that involve them once being incestuous cannibals before they became civilised, in this way referencing the ideas expressed by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud in his Totem and Taboo. He then proceeds to discuss a variety of other related issues, such as the connection between cannibalism and witchcraft, the role of gender and class in cannibal claims, and the role of the Eucharist.[13]

In "The Mythical World of Anthropology", Arens looks at the manner in which anthropologists have approached the idea of cultural cannibalism. Noting the widespread western idea that cannibals exist "beyond the pale of civilization", in the land of savagery and primitivism, he argues that anthropologists have taken it upon themselves to explain and rationalize the cannibalism of such "primitives" without first proving that they were cannibalistic to start with. He connects this to the attitude held by many westerners both past and present that they are the bearers of civilization who have helped to put a stop to cannibalism. Challenging and criticizing the anthropological community's long-term advocacy of what he considers the "Man-Eating Myth", he draws comparisons with the belief in demonic witchcraft and cannibalism in Europe that led to the witch trials of the Early Modern period, ending his work on a quote from the historian Norman Cohn's book Europe's Inner Demons.[14]

Main arguments

The existence of cultural cannibalism

In The Man-Eating Myth, Arens notes that he was unable to find any form of "adequate documentation" for the existence of socially sanctioned cannibalism in any recorded society.[15] As such, he remained "dubious" that cannibalism has ever existed as an approved social activity.[8] He nevertheless refused to rule out the possibility that it had ever occurred, maintaining that the correct methodological stance was to hold an open mind on the issue, and that it would be impossible to conclusively state that no society throughout human history has ever culturally sanctioned cannibalism.[16] From this definition of "cultural cannibalism" he excludes those instances where people have resorted to cannibalism under survival conditions, or where individuals have committed cannibalism as an anti-social activity that is condemned by the rest of their community.[8]

The universal belief in cultural cannibalism

Arens considers the belief in cannibalism to be a "universal phenomenon" that has been exhibited in all inhabited regions of the world.[17] He expresses his view that "all cultures, subcultures, religions, sects, secret societies and every other possible human association have been labeled anthropophagic by someone".[17] He notes that accusations of socially sanctioned cannibalism in a society typically arise from an alternative society with whom they are often in conflict. As evidence, he notes that pagan Romans labelled the early Christians as cannibals, despite the lack of any evidence for this, and subsequently Christians in Medieval Europe labelled Jews as cannibals, again without any corroborating evidence.[18]

He argues that across the world, cannibals are viewed as non-human entities, committing acts that no human would ordinarily perpetrate. In this way they were akin to various non-human species of animal, and Arens notes that in some societies, cannibals are believed to physically transform into different species in order to kill and consume humans.[19]

Arens proceeds to ponder the question as to why societies across the world believe that other, exotic societies exhibit cannibalism. He notes that the development of a "collective prejudice" against a foreign entity provides meaning for the group by conjuring up an opposite who commit social taboos.[20] He also suggests that one society's belief that a foreign society is cannibalistic might arise from an inability to differentiate between the latter's conceptions of the natural and the supernatural. As evidence, he asserts that rumors that the Indigenous Americans of Northeastern Canada were cannibals arose when foreign societies learned of their folkloric beliefs in man-eating giants who lived in the wilderness and conflated this fantasy with reality.[21]

The anthropological approach to cultural cannibalism

Arens' third primary argument is that ever since the development of the discipline, the anthropological community have continually perpetuated the "Man-Eating Myth" that cultural cannibalism was widespread across the world. In this way, he sees anthropologists as following in the path of Christian friars from the Early Modern period who asserted the existence of cannibalism "beyond the pale of civilization", in societies that are either historically or geographically distinct to western culture.[22] He furthermore argues that both Christian proselytizers and academic anthropologists have sought to accuse non-western, non-Christian peoples of cultural cannibalism in order to then explain and rationalize their "savage" ways; in doing so, he argues, they continue to portray the Christian west as a civilizing influence on the world that suits their own socio-political agendas. In this way, Arens feels that the "Man-Eating Myth" furthers the "we–they" dichotomy between westerners and non-westerners,[23] and has indirectly lent some justification for the western exploitation of "savage" non-western peoples.[24]

He does not believe that there was any conscious academic conspiracy to spread the claims of cultural cannibalism, instead believing that they have arisen as a result of poor methodologies that have been used in this area, namely a lack of properly scrutinizing sources.[25] He furthermore suggests that anthropologists have failed to tackle this issue because – while novel ideas are certainly welcomed – they feared that by criticising long-held core assumptions, they would be upsetting the established status quo within the discipline, and would ultimately tarnish the reputation of anthropology itself by suggesting that it had made major errors.[26]

Reception

Academic reviews

Even if one could concede that cannibalism exists primarily as a cultural construct whose expression only involves actual physical consumption of human flesh on rare occasions, which I am prepared to do, Arens still leaves little room for fleshing out the culture of cannibalism because he has buried the bones in a tomb of overly constrained empiricism. The cant from Arens seems to be that if cannibalism can be shown to be anchored in the murky world of mythic thought, metaphoric equations, and symbolic actions, then it has a chance of being reduced to that existence alone.

– Ivan Brady, 1982.[27]

The Man-Eating Myth was reviewed by Ivan Brady for the American Anthropologist journal. He noted that the framework for Arens' scepticism was not coherent and was never spelled out explicitly in the text, even if it could be deduced from reading the entirety of the work. Brady sees this framework as an "unsophisticated" version of positivism and naturalism, an approach that he laments was becoming increasingly popular in anthropology. Casting a critical eye over Arens' scepticism, he admits to being perplexed as to why only "direct observation" will do as evidence, pondering whether Arens would accept anything short of affidavits by practicing cannibals as evidence for the practice. Brady notes that there are other activities in the world that surely go on – such as masturbation in monasteries and homosexual activity in the armed forces – but that these would be hidden by a veil of secrecy and therefore difficult to observe directly, suggesting that the same may be true for cannibalism. Moving on, Brady attacks Arens' criticism of anthropology, believing that he has constructed a straw man argument by comparing the early accounts of travellers to the later, 20th-century accounts of anthropologists, and lambasts him for portraying himself as an objective figure in the debate. He argues that in cases such as that of the Carib people, the evidence for cannibalism is "indeterminate", rather than negative, as Arens believes. Concluding his review, Brady admits that he agrees with Arens' premise that socially accepted cannibalism is not as globally widespread as some anthropologists have suggested, but disagreed that anthropologists have been as "reckless" in their claims as Arens charges, and furthermore disagrees with Arens' suggestion that the cause can be blamed on poor observation standards.[28]

The journal Man published a highly negative review by P. G. Rivière of the University of Oxford. Criticizing what he saw as the "chatty 'Holier-than-Thou' tone" of the book, Rivière asserted that at only 160 pages of text, Arens had failed to give sufficient attention to the subject and evidence, instead devoting much of the space to constructing and demolishing straw men arguments. Coming to the defence of those who believe the account of Staden regarding cannibalism among the Tupinambá by arguing that it could indeed reflect the German explorer's genuine experiences, Rivière notes that Arens has not tackled all of the claims which assert that this South American people committed anthropophagy. Furthermore, he expresses his opinion that Arens' work has made him reassess the evidence for Tupinambá cannibalism, of whose existence he is now even more thoroughly convinced. Proclaiming it to be both a "bad" and a "dangerous" book, he finally expresses his fear that it might prove to be "the origin of a myth".[7] Similarly, Shirley Lindenbaum of the New School for Social Research published her highly negative review of Arens' work in the journal Ethnohistory. Casting a critical eye on his claims, she notes that his use of source material was "selective and strangely blinkered", which detracted from his ideas of "collective prejudice" which she considers valuable. Critiquing his discussion of the Fore people of New Guinea as being littered with inaccuracies, she draws comparisons between cannibalism and sexual activity, noting the latter is also not directly observed by anthropologists but nonetheless undoubtedly goes on. She furthermore expresses surprise that the work was ever designed for a scholarly audience because of its poor levels of accuracy.[29]

James W. Springer of Northern Illinois University reviewed Arens' book for Anthropological Quarterly. He hoped that the book would in part have a positive legacy, in that it might make anthropologists look more closely and critically at their source material, and praised its criticism of the claims regarding Aztec cannibalism. He nevertheless proclaimed that Arens was "almost certainly wrong", making use of faulty evaluation methods and being excessively critical of any and all claims for cultural cannibalism, failing to prove dishonesty or prejudice on the behalf of Europeans who have claimed evidence for cultural cannibalism. He criticises both Arens' treatment of Staden's claims and his discussion of Iroquois cannibalism, claiming that Arens has neglected to mention many Native American first-hand testaments as to the cannibalistic nature of these people. Ultimately, he dismissively asserted that The Man-Eating Myth "does not advance our knowledge of cannibalism".[30] More favourably, R.E. Downs of the University of New Hampshire reviewed the work for American Ethnologist. Noting that the book was "provocative" in its thesis, he felt that it was bound to raise many "hackles", and that it would lead future anthropologists to challenge other long-standing beliefs about non-western "primitive" societies, such as that of widespread incest and promiscuity. Ultimately, he remarked that while many anthropologists might dispute Arens' ideas, never again could they claim that the existence of cultural cannibalism was an undisputed fact.[31]

In sum, this book is only partially successful. Arens succeeds in demonstrating that the evidence for cannibalism is often weak, even for the best documented examples. He also presents interesting hypotheses on the subject of why people in general, and anthropologists in particular, are so willing to accept its existence despite this lack of evidence. The ideas in this book should serve to stimulate further investigations of these topics. Unfortunately, however, Arens fails to support satisfactorily his main thesis that no adequate documentation for cannibalism exists for any culture, an argument that seems too much the result of the author's personal convictions and too little the product of careful research.

– Thomas Krabacher, 1980.[32]

The geographer Thomas Krabacher of the University of California undertook a review of The Man-Eating Myth for the journal Human Ecology. Believing that a critical study of cannibal claims has been long needed, he was nevertheless perturbed that Arens' work failed to be either comprehensive or objective. Although concurring that reports of cannibalism have been all too readily accepted without being properly scrutinized, Krabacher nonetheless argues that he has used a "careless and selective" approach to the literary sources. He also sees problems in Arens' approach to the nature of the evidence, stating that the anthropologist has not given sufficient thought to what would constitute reliable testimony in the case of cannibalism. Drawing comparisons with sexual behaviour, he notes that it would not always be possible for a western anthropologist to directly view cannibalism, which would likely be hidden from their view by many practitioners, and that as such, second-hand accounts would have to do. He then critiques Arens' writing style, believing it to be "contentious and possibly offensive", and highlighting a number of typological errors.[32]

Khalid Hasan's review of The Man-Eating Myth appeared in the Third World Quarterly journal. Considering it to be a "brilliant and well documented" tome, he praised Arens' "admirable" work and expressed his hope that others would expand on his initial thesis.[33] The German journal Anthropos published a largely positive review of Arens' work by John W. Burton, in which he described it as an "extensive and meticulous" study which was the model of a "fair and reasoned argument". Supporting Arens' arguments, he proclaimed that the final chapter should be essential reading for all anthropologists.[34] P. Van de Velve reviewed the book for the Dutch journal Anthropologica. Van de Velve felt that the book contained several weaknesses, for instance Arens did not, he notes, explain how the claim for cultural cannibalism can be successfully refuted. The Dutch scholar also noted that the argument that anthropology focused on examining "non-bourgeoisie" cultures was not new. Ultimately however, Van de Velve considered it to be a well written book that offered "good reading", particularly for students.[35]

Subsequent academic reception

Archaeologist Paola Villa, one of the primary excavators of Fontbrégoua Cave, a Neolithic site in Southeastern France where the team argued for the existence of cannibalism, made reference to Arens' work in a 1992 paper of his published in the Evolutionary Anthropology journal. Villa noted that following the book's publication, prehistorians always dealt with suspicions of cannibalism with "extreme reluctance and scepticism".[36]

The English archaeologist Timothy Taylor critically discussed Arens' work in his book The Buried Soul: How Humans Invented Death (2002). Proclaiming that "there is now overwhelming biological, anthropological and archaeological evidence that cannibalism was once all around us", he attacked Arens for his blanket and "bizarre" accusations against the concept of cultural anthropophagy. He argued that The Man-Eating Myth had become so influential upon publication because it was what a generation of anthropological and archaeological students wanted to hear, not because it represented a coherent argument, citing P.G. Rivière's negative review in Man. Commenting on the situation in archaeology, he felt that following the publication of Arens' work, archaeologists had ceased to cite cannibalism as an explanation, to the detriment of the discipline itself. Presenting evidence to counter Arens' claims, Taylor cites the accounts of cannibalism among Pom and Passon, two chimpanzees of Gombe National Park whose anti-social activities were recorded by Jane Goodall, and from this discusses the evolutionary benefits of cannibalism. Proceeding to defend various ethnographic accounts of cultural cannibalism, he argues that this thoroughly disproves the beliefs which "Arensite" anthropologists find it "comfortable or fashionable" to believe.[37] Later in The Buried Soul, he proclaims that Arens' book is pervaded by a "hollow certainty of viscerally insulated inexperience", and he claims that such a flawed methodology has echoes in the anthropologist Jean La Fontaine's Speak of the Devil: Tales of Satanic Abuse in Contemporary England (1998); Taylor himself suggests that multiple claims of the Satanic ritual abuse have been incorrectly dismissed for being considered "improbable".[38]

Reviewing the state of cannibalism research more than 20 years after her initial review of the book, Lindenbaum noted that, while after "Arens['s] ... provocative suggestion ... many anthropologists ... reevaluated their data", the outcome was not a confirmation of his claims, but rather an improved and "more nuanced" understanding of where, why and under which circumstances cannibalism took place: "Anthropologists working in the Americas, Africa, and Melanesia now acknowledge that institutionalized cannibalism occurred in some places at some times. Archaeologists and evolutionary biologists are taking cannibalism seriously."[2]

Arens' book was also briefly mentioned by the Scottish archaeologist Ian Armit in his book, Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (2012). Armit noted that though the book was influential, most anthropologists would "probably" argue that Arens' wholesale dismissals had gone "too far". He also saw Arens' work as symptomatic of a trend within anthropology to neglect the "undesirable" cultural practices of non-western societies.[39]

Claude Lévi-Strauss summarily dismissed Arens's work, calling it "a brilliant but superficial book that enjoyed great success with an ill-informed readership", but failed to convince the academic community: "No serious ethnologist disputes the reality of cannibalism".[1]

Several researchers have evaluated Arens's statements regarding specific regions, generally finding them incomplete and misleading. Thomas Abler investigated Arens's dismissal of Iroquois cannibalism, concluding that his summary rejection of many detailed accounts cannot be justified and that he totally overlooked important other sources.[40] He finished by calling Arens's book an example of "sloppy scholarship" and "ignorance" that failed to shed new light on Iroquois customs.[41] Donald Forsyth critically examined Arens's dismissal of Hans Staden's travel report, concluding that, despite Arens's attempts to show the opposite, "the basic reliability of [Staden's] story is beyond reasonable doubt."[42] Christian Siefkes analyzed Arens's discussion of the Congo Basin, showing that Arens misleadingly quoted several sources – claiming, for example, that David Livingstone had found no evidence of cannibalism in the Maniema region, while Livingstone's diary shows in fact the opposite – and totally overlooked many others.[43]

Criticism of ethnocentrism in Arens's work

Lindenbaum[44] and others have pointed out that Arens displays a "strong ethnocentrism". His refusal to admit that cultural (or institutionalized) cannibalism ever existed seems to be motivated by the implied idea "that cannibalism is the worst thing of all" – worse than any other behavior people engaged in, and therefore uniquely suited to vilify others. Kajsa Ekholm Friedman called this "a remarkable opinion in a culture [the European/American one] that has been capable of the most extreme cruelty and destructive behavior, both at home and in other parts of the world."[45]

She observed that "[i]n many parts of the Congo region there was no negative evaluation of cannibalism", in contrast to Arens's claim that it was universally despised. In the Congo, however, many "expressed their strong appreciation of this very special meat and could not understand the hysterical reactions from the white man's side."[46] Why indeed, she goes on to ask, should they have had the same negative reactions to cannibalism as Arens and his contemporaries? His argument is based on the implicit idea that everybody throughout human history must have shared the strong taboo placed by his own culture on cannibalism, but he never even attempts to explain why this should be so, and "neither logic nor historical evidence justifies" this viewpoint, as Siefkes commented.[47]

Press attention

Arens' book gained attention from the popular press soon after its publication.[48]

References

Footnotes

- Lévi-Strauss 2016, p. 87.

- Lindenbaum 2004, pp. 475–76, 491.

- Scott & McMurry 2011, p. 216.

- Arens 1979. pp. 10–13.

- Arens 1979. p. v.

- Arens 1979. pp. 172–173.

- Rivière 1980.

- Arens 1979. p. 9.

- Arens 1979. pp. 5–40.

- Arens 1979. pp. 41–80.

- Arens 1979. pp. 82–116.

- Arens 1979. pp. 119–136.

- Arens 1979. pp. 139–161.

- Arens 1979. pp. 163–185.

- Arens 1979. p. 21.

- Arens 1979. pp. 180–181.

- Arens 1979. p. 139.

- Arens 1979. p. 19.

- Arens 1979. pp. 140–141.

- Arens 1979. p. 145.

- Arens 1979. pp. 150–151.

- Arens 1979. p. 165.

- Arens 1979. pp. 167–169.

- Arens 1979. p. 184.

- Arens 1979. p. 175.

- Arens 1979. pp. 176–177.

- Brady 1982. p. 606.

- Brady 1982.

- Lindenbaum 1982.

- Springer 1980.

- Downs 1980.

- Krabacher 1980.

- Hasan 1980.

- Burton 1980.

- Van de Velve 1982.

- Villa 1992. p. 94.

- Taylor 2002. pp. 57–85.

- Taylor 2002. pp. 280–283.

- Armit 2012. p. 50.

- Abler 1980.

- Abler 1980, p. 314.

- Forsyth 1985, p. 25.

- Siefkes 2022, pp. 292–294.

- Lindenbaum 2004, p. 476.

- Ekholm Friedman 1991, p. 220.

- Ekholm Friedman 1991, p. 221.

- Siefkes 2022, p. 294.

- Brady 1982. p. 595.

Bibliography

- Abler, Thomas S. (1980). "Iroquois Cannibalism: Fact Not Fiction". Ethnohistory. 27 (4): 309–316. doi:10.2307/481728. JSTOR 481728.

- Arens, William (1979). The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502793-8.

- Armit, Ian (2012). Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87756-5.

- Brady, Ivan (1982). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". American Anthropologist. Vol. 84, no. 3. pp. 595–611. JSTOR 677335.

- Burton, John W. (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Anthropos. Vol. Bd. 75, H. 3./4. pp. 644–645. JSTOR 40460213.

- Downs, R. E. (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". American Ethnologist. Vol. 7, no. 4. pp. 785–786. JSTOR 643487.

- Ekholm Friedman, Kajsa (1991). Catastrophe and Creation: The Transformation of an African Culture. Amsterdam: Harwood.

- Forsyth, Donald W. (1985). "Three Cheers for Hans Staden: The Case for Brazilian Cannibalism". Ethnohistory. 32 (1): 17–36. doi:10.2307/482091. JSTOR 482091.

- Harris, Marvin (1986). Good to Eat: Riddles of Food and Culture. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-04-306002-5.

- Hasan, Khalid (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Third World Quarterly. Vol. 2, no. 4. pp. 812–813. JSTOR 3990902.

- Krabacher, Thomas (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Human Ecology. Vol. 8, no. 4. pp. 407–409. JSTOR 4602573.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude (2016). We Are All Cannibals, and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lindenbaum, Shirley (1982). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Ethnohistory. Vol. 29, no. 1. pp. 58–60. JSTOR 481011.

- Lindenbaum, Shirley (2004). "Thinking about Cannibalism". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 475–498. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143758. S2CID 145087449.

- Riviere, P. G. (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Man. Vol. 15, no. 1. pp. 203–205. JSTOR 2802019.

- Scott, Richard; McMurry, Sean (2011). "The Delicate Question: Cannibalism in Prehistoric and Historic Times". In Dixon, Kelly J.; Schablitsky, Julie M.; Novak, Shannon A. (eds.). An Archaeology of Desperation: Exploring the Donner Party's Alder Creek Camp. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 211–244.

- Siefkes, Christian (2022). Edible People: The Historical Consumption of Slaves and Foreigners and the Cannibalistic Trade in Human Flesh. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 9781800736139.

- Springer, James W. (1980). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Anthropological Quarterly. Vol. 53, no. 2. pp. 148–150. JSTOR 3317738.

- Taylor, Timothy (2002). The Buried Soul: How Humans Invented Death. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-4672-2.

- Van de Velde, P. (1982). "Review of The Man-Eating Myth". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde ANTHROPOLOGICA XXIV. Vol. 138, no. 1. pp. 184–185. JSTOR 27863421.

- Villa, Paola (1992). "Cannibalism in Prehistoric Europe". Evolutionary Anthropology. Vol. 1, no. 3. pp. 93–104.