The Metropolitan Theatre

The Metropolitan Theatre was a London music hall and theatre in Edgware Road, Paddington. Its origins were in an old inn on the site where entertainments became increasingly prominent by the early 19th century. A new theatre was built there in 1836, replaced in 1897 by a new building designed by the theatre architect Frank Matcham. The Metropolitan was a leading theatre for music hall and variety, but with the decline of the latter in the mid-20th century it struggled to survive, and was demolished in 1964 to make way for a road-widening scheme.

1836 Turnham's Grand Concert Hall 1864 Metropolitan Music-Hall 1875 The Metropolitan 1920s Metropolitan Theatre of Varieties 1950s Metropolitan Music-Hall[1] | |

| Address | 267 Edgware Road, Paddington[2] Westminster, London |

|---|---|

| Designation | Demolished |

| Type | Music hall and variety theatre |

| Capacity | 2,000 (1836); 2,800 (1897) 1,542 (1963) |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1836 |

| Closed | 1963 |

| Rebuilt | 1897 (Frank Matcham) |

Early years

From the 16th century the village of Padynton, about a mile north-west along the road to Edgware from Tyburn had contained a well known inn, the White Lion, whose licence was believed to date back to 1524. It was rebuilt in 1836, when a hall or concert room was added to the premises. Performances there began to take the form later recognised as early music-hall; the rooms became known as Turnham's after the owner and licensee John Tumham.[1]

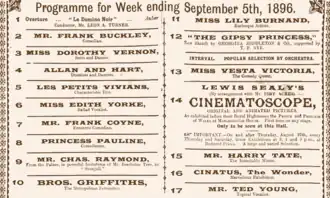

Under Turnham's management the hall was rebuilt on a large scale, with a capacity of 2,000, opening on 8 December 1862 as Turnham's Grand Concert Hall.[1] The hall benefited from the opening of a new Metropolitan line station at Edgware Road the following year, which made it easily accessible to Londoners from other districts.[1] After changes of management the building was renamed the Metropolitan Music-Hall, opening under that name on 28 March 1864. It prospered over the following three decades, but by the 1890s it was recognised that the building was, as The Era put it, "out of date and old-fashioned".[3]

In 1897 it was decided to rebuild completely from designs by Frank Matcham. Part of the old White Lion inn was retained between the two entrances to the new building. The Era of 25 December 1897 reported:

Of the auditorium, The Era commented:

The new theatre opened on 22 December 1897 with a variety programme that included the singer and comedian Tom Costello, the "Coster Comedienne" Kate Carney, the ventriloquist Fred Russell, the yodelling Alexandra Dagmar, the Villion Troupe of acrobatic bicyclists and "Mr Fred Leslie's leaping dogs".[3]

20th century

Further alterations were made in 1905 when the old inn was demolished to make way for a central entrance.[4] The theatre historians Mander and Mitchenson commented in 1963 that during the first half of the twentieth century "the pattern of entertainment at the 'Met' follows the rise and fall of variety, the era of touring revue, through to its complete decline in recent years".[4] During the 20th century the capacity of the theatre was reduced to 1,542,[1] but even after this it remained one of the ten largest London theatres.[5]

By the late 1950s the Metropolitan was nearing the end of its existence. The London County Council earmarked the building for compulsory acquisition and demolition to make way for the widening of the Edgware Road and the construction of the Westway fly-over.[6] Among the highlights of the Metropolitan's last years was a 1957 performance by Max Miller, of which an audio recording survives,[7] described in a 2013 study as "the classic recording of comedy in performance".[8]

The television presenter, writer and Music Hall enthusiast Daniel Farson writes about the final days of "The Met" in his 1973 book Marie Lloyd and Music Hall. He also produced an L.P album, Daniel Farson Presents... Music Hall, recorded live at the theatre in 1961 in an attempt to capture the atmosphere of the theatre. The album features performances from Hetty King, Albert Whelan, Ida Barr, G.H. Elliot, Billy Danvers and Marie Lloyd Jr.

In the last three years of the theatre's existence, various managements presented a range of shows, including Old Time Music-Hall, opera, an Irish Variety season, visits from touring companies, including one from Dublin, presenting Posterity be Damned, a play by Dominic Behan, in a short-lived attempt to establish an Irish Theatre in London.[4][9] The theatre closed except for occasional shows, and wrestling matches on Saturdays. For a time it was used as a television studio.[9] The last performance given at the Metropolitan was a packed all-star farewell bill on Good Friday, 12 April 1963, compered by Tommy Trinder with stars from earlier times including Hetty King, Issy Bonn and Ida Barr and new ones including Mrs Shufflewick, Dickie Valentine and Ted Ray.[10] The building was demolished in September 1963.[11]

References and sources

References

- Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 232–233

- Howard, p. 151

- "The New Metropolitan", The Era, 25 December 1897, p. 16

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 234

- Gaye, pp. 1553–1554

- "New Life for the Old Metropolitan", The Sphere, 11 April 1959, p. 33

- "Max at the Met", Pye LP OCLC 755912483

- Fisher, p. 103

- Hartnoll, Phyllis, and Peter Found. "Metropolitan Music-Hall.", The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre, Oxford University Press, 1996. Retrieved 6 July 2020. (subscription required)

- "The Metropolitan Theatre of Varieties", Illustrated London News, 27 April 1963, p. 629; and "The Days When Music Played at the Metropolitan", w9w2. Retrieved 6 July 2020

- "Flowers, Jewels and Floodlight", Illustrated London News, 28 September 1963, p. 460

Sources

- Fisher, John (2013). Funny Way to Be a Hero. London: Preface Books. ISBN 978-1-84809-313-3.

- Gaye, Freda, ed. (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.

- Howard, Diana (1986). London Theatres and Music Halls: 1850-1950. Library Association. ISBN 978-0-85365-471-1.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (1963). The Theatres of London (second ed.). London: Rupert Hart-Davis. OCLC 1077976337.