The Misadventures of Merlin Jones

The Misadventures of Merlin Jones is a 1964 American science-fiction comedy film directed by Robert Stevenson and produced by Walt Disney Productions. The film stars Tommy Kirk as a college student who experiments with mind-reading and hypnotism, leading to run-ins with a local judge. Annette Funicello plays his girlfriend (and sings the film's title song, accompanied by Disneyland's very own harmony quartet, The Yachtsmen, written by the Sherman Brothers),[3] with Leon Ames, Stuart Erwin, Alan Hewitt, Connie Gilchrist, and Dallas McKennon rounding out the film's supporting cast. This film was followed up by a sequel called The Monkey's Uncle the following year.[4]

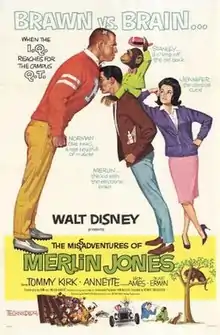

| The Misadventures of Merlin Jones | |

|---|---|

Official theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Stevenson |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | Bill Walsh |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Edward Colman |

| Edited by | Cotton Warburton |

| Music by | Buddy Baker |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $4,000,000 (US/ Canada)[2] |

Plot

Midvale College student Merlin Jones (Tommy Kirk), who is always involved with mind experiments, designs a helmet that connects to an electroencephalographic tape that records mental activity. He is brought before Judge Holmsby (Leon Ames) for wearing the helmet while driving and his license is suspended. Merlin returns to the lab and discovers accidentally that his new invention enables him to read minds.

Judge Holmsby visits the diner where Merlin works part-time, and Merlin, through his newly found powers, learns that the judge is planning a crime. After informing the police, he is disregarded as a crackpot. Merlin and Jennifer (Annette Funicello), his girlfriend, break into Judge Holmsby's house looking for something to prove Holmsby's criminal intent, but are arrested by the police. Holmsby then confesses that he is the crime book author "Lex Fortis", and asks that this identity be kept confidential.

Merlin's next experiment uses hypnotism. After hypnotizing Stanley, Midvale's lab chimp, into standing up for himself against Norman (Norm Grabowski), the bully student in charge of caring for Stanley, Merlin gets into a fight with Norman, and is brought before Judge Holmsby again. Intrigued by Merlin's experiments, the judge asks for Merlin's help in constructing a mystery plot for his next book.

Working on the premise that no honest person can be made to do anything they would not do otherwise – especially commit a crime – Merlin hypnotizes Holmsby, and instructs him to kidnap Stanley. Shocked when the judge actually commits the crime, Merlin and Jennifer return the chimp, but are charged for the theft themselves. The judge sentences Merlin to jail, completely unaware of his own role in the crime. Livid at the injustice, Jennifer persuades Holmsby of his own guilt, and the good judge admits that a little dishonesty might exist in everybody.

Cast

- Tommy Kirk as Merlin Jones

- Annette Funicello as Jennifer

- Leon Ames as Judge Holmsby/Lex Fortas

- Stuart Erwin as Police Captain Loomis

- Alan Hewitt as Professor Shattuck

- Connie Gilchrist as Mrs. Gossett

- Dallas McKennon as Detective Hutchins

- Norm Grabowski as Norman

- Kelly Thordsen as Motorcycle Cop (uncredited)

Production

Though the film credits story credits to "Tom and Helen August", the names are pseudonyms for Alfred Lewis Levitt and Helen Levitt, who were blacklisted in Hollywood.[5]

Tommy Kirk and Annette Funicello had previously starred in two films for Disney made for US television, but released theatrically in other markets, The Horsemasters and Escapade in Florence. This was originally made for television, but Disney decided to release it theatrically.[6] However, Disney has never officially stated whether this film was initially two episodes of a planned television series,[7] but at least one critic, Eugene Archer, of The New York Times, wrote upon its release:

Movies made for television are commonplace these days, but the idea of screening television shows in movie theaters is still farfetched. Who is expected to spend the $2? Strange as it sounds, this seems to be the explanation behind Walt Disney's latest hit, The Misadventures of Merlin Jones. It is a pastiche of two separate stories with the same set of characters, each running less than an hour (leaving time for commercials), stitched together in the middle and released yesterday in neighborhood theaters.[8]

Filming took place in January 1963.[9]

In March 1963, NBC was pleased with Annette Funicello that they wanted Disney to make two more films with the same character.[10] It appears that Disney then decided to release the film theatrically.

Reception

Critical

Eugene Archer of The New York Times panned the film as "cheap situation comedy" and "the kind of picture usually dismissed by shrugging, 'Well, at least the kids will like it'. Unless that is, your children happen to be bright".

Box office

Although critics were not impressed, audiences seemed to love it, as the film grossed over $4 million in North America, surprising even Disney.[11] E. Carton Walker, Disney's vice president in charge of advertising commented that "nobody knows what a picture will do. Merlin Jones grossed $4 million... and surprised everybody".[12]

It made enough money to encourage a sequel in 1965.[13]

References

- "The Misadventures of Merlin Jones – Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- "Updated All-time Film Champs", Variety, 9 January 1974 p 60. Please note figure is rentals accruing to distributors.

- "The Misadventures of Merlin Jones". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 31 (368): 136. September 1964.

- Funicello, Annette; Bashe, Patricia Romanowski (1994). A dream is a wish your heart makes: my story. Hyperion. p. 135.

- Variety, April 3, 1997

- Scheuer, Philip K. (Mar 27, 1966). "TV at Bottom of Movie Barrel, Makes Own". Los Angeles Times. p. b5.

- SciFilm.org Archived 2010-12-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Archer, Eugene (March 26, 1964). "'Misadventures of Merlin Jones' Opens". The New York Times p. 40.

- "Filmland Events: Miss Pickford, Lloyd Will Receive Honor". Los Angeles Times. Jan 3, 1963. p. C7.

- "ABC Planning the Shocker of All Time". Chicago Tribune. Mar 16, 1963. p. d19.

- Vagg, Stephen (9 September 2019). "The Cinema of Tommy Kirk". Diabolique Magazine.

- VanderVeld, Richard L. (July 18, 1965). "Disney: Self-Perpetuating Money Machine: 'Mary Poppins' Works Her Magic for Happy Shareowners". Los Angeles Times. p. h1.

- Scheuer, Philip K. (Jan 4, 1965). "Disney Announces Diverse Schedule: Doris Day Winner (Again); Ill Wind a Boon to Actors". Los Angeles Times. p. B7.