The Old Vic

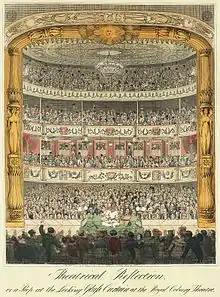

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, not-for-profit producing theatre in Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Theatre. In 1871 it was rebuilt and reopened as the Royal Victoria Palace. It was taken over by Emma Cons in 1880 and formally named the Royal Victoria Hall, although by that time it was already known as the "Old Vic". In 1898, a niece of Cons, Lilian Baylis, assumed management and began a series of Shakespeare productions in 1914. The building was damaged in 1940 during air raids and it became a Grade II* listed building in 1951 after it reopened.[3]

Royal Coburg Theatre Royal Victoria Theatre Royal Victoria Palace Royal Victoria Hall and Coffee Tavern | |

The exterior of the Old Vic from the corner of Baylis Road and Waterloo Road | |

| Address | The Cut London, SE1 England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.5022°N 0.1096°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Old Vic Theatre Trust 2000 |

| Designation | Grade II* listed |

| Type | Non-commercial theatre |

| Capacity | 1,067 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1818 |

| Rebuilt | 1871: J. T. Robinson 1880/1902: Elijah Hoole 1922/1927: Matcham & Co.,(under F. G. M. Chancellor)[1] 1933–38: F. Green & Co 1950: Pierre Sonrel 1960: Sean Kenny[2] 1983: Renton, Howard, Wood & Levine |

| Years active | 1818–present |

| Architect | Rudolphe Cabanel of Aachen |

| Website | |

| oldvictheatre.com | |

The Old Vic is the crucible of many of the performing arts companies and theatres in London today. It was the name of a repertory company that was based at the theatre and formed (along with the Chichester Festival Theatre) the core of the National Theatre of Great Britain on its formation in 1963, under Laurence Olivier. The National Theatre remained at the Old Vic until new premises were constructed on the South Bank, opening in 1976. The Old Vic then became the home of Prospect Theatre Company, at that time a highly successful touring company which staged such acclaimed productions as Derek Jacobi's Hamlet. However, with the withdrawal of funding for the company by the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1980 for breaching its touring obligations, Prospect disbanded in 1981. The theatre underwent complete refurbishment in 1985. In 2003, Kevin Spacey was appointed artistic director, which received considerable media attention.[4] Spacey served as artistic director until 2015; two years after he stepped down, he was accused of sexually harassing and assaulting several people.[5] In 2015, Matthew Warchus succeeded Spacey as artistic director.[6]

History

Origins

The theatre was founded in 1818 by James King and Daniel Dunn (formerly managers of the Surrey Theatre in Bermondsey), and John Thomas Serres, then the marine painter to the King. Serres managed to secure the formal patronage of Princess Charlotte and her husband Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, and named the theatre the Royal Coburg Theatre. The theatre was a "minor" theatre (as opposed to one of the two patent theatres) and was thus technically forbidden to show serious drama. Nevertheless, when the theatre passed to George Bolwell Davidge in 1824 he succeeded in bringing legendary actor Edmund Kean south of the river to play six Shakespeare plays in six nights. The theatre's role in bringing high art to the masses was confirmed when Kean addressed the audience during his curtain call saying "I have never acted to such a set of ignorant, unmitigated brutes as I see before me." More popular staples in the repertoire were "sensational and violent" melodramas demonstrating the evils of drink, "churned out by the house dramatist", confirmed teetotaller Douglas Jerrold.[7]

When Davidge left to take over the Surrey Theatre in 1833, the theatre was bought by Daniel Egerton and William Abbot, who tried to capitalise on the abolition of the legal distinction between patent and minor theatres, enacted in Parliament earlier that year.[8] On 1 July 1833,[9] the theatre was renamed the Royal Victoria Theatre, under the "protection and patronage" of Victoria, Duchess of Kent, mother to Princess Victoria, the 14-year-old heir presumptive to the British throne. The duchess and the princess visited only once, on 28 November of that year, but enjoyed the performance, of light opera and dance, in the "pretty...clean and comfortable" theatre. The single visit scarcely justified the "Old Vic" its later billing as "Queen Victoria's Own Theayter".[8][10][11]

In 1841, David Osbaldiston took over as lessee, and was succeeded on his death in 1850 by his lover and the theatre's leading lady, Eliza Vincent, until her death in 1856. Under their management, the theatre remained devoted to melodrama. In 1858, sixteen people were crushed to death inside the theatre after mass panic caused while an actor's clothing caught fire.[12]

[13] In 1867, Joseph Arnold Cave took over as lessee. In 1871 he transferred the lease to Romaine Delatorre, who raised funds for the theatre to be rebuilt in the style of the Alhambra Music Hall. Jethro Thomas Robinson was engaged as the architect. In September 1871 the old theatre closed, and the new building opened as the Royal Victoria Palace in December of the same year, with Cave staying on as manager. By 1873, however, Cave had left and Delatorre's venture failed.[14]

In 1880, under the ownership of Emma Cons (for whose memory there are plaques outside and inside the theatre) it became the Royal Victoria Hall and Coffee Tavern and was run on "strict temperance lines"; by this time it was already known as the "Old Vic".[15] The "penny lectures" given in the hall led to the foundation of Morley College. An endowment from the estate of Samuel Morley led to the creation of the Morley Memorial College for Working Men and Women on the premises, which were shared; lectures were given back stage, and in the theatre dressing rooms. The adult education college moved to its own premises nearby in the 1920s.

On 24 November 1923, the theatre participated in a pioneering radio event, when the first set of the opera La Traviata was broadcast live by the BBC, using transmitters in London, Manchester and Glasgow, via a specially installed relay transmitter on the roof of the adjacent Royal Victoria Tavern.[16][17]

Old Vic company

With Emma Cons's death in 1912 the theatre passed to her niece Lilian Baylis, who emphasised the Shakespearean repertoire. The first radio broadcasts from the theatre were made as early as October 1923, by the British Broadcasting Company.[18] The Old Vic Company was established in 1929, led by Sir John Gielgud. Between 1925 and 1931, Lilian Baylis championed the re-building of the then-derelict Sadler's Wells Theatre, and established a ballet company under the direction of Dame Ninette de Valois. For a few years the drama and ballet companies rotated between the two theatres, with the ballet becoming permanently based at Sadler's Wells in 1935. Baylis died in November 1937.[19]

Wartime exile

The Old Vic was damaged badly during the Blitz, and the war-depleted company spent all its time touring, based in Burnley, Lancashire at the Victoria Theatre during the years 1940 to 1943. In 1944, the company was re-established in London with Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier as its stars, performing mainly at the New Theatre (now the Noël Coward Theatre) until the Old Vic was ready to reopen in 1950. In 1946, an offshoot of the company was established in Bristol as the Bristol Old Vic.

The Five Year plan

In 1953, Michael Benthall became the Artistic Director. Michael devised the Five Year plan during his tenure. The plan was to produce Shakespeare's First Folio in five years, starting the plan with Hamlet, starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom as Hamlet and Ophelia respectively, and ending the plan with Hamlet, starring John Neville and Judi Dench in the leading roles. Michael remained at the Old Vic company until 1962.

National Theatre company

In 1963, the Old Vic company was dissolved and the new National Theatre Company, under the artistic direction of Sir Laurence Olivier, was based at the Old Vic until its own building was opened on the South Bank near Waterloo Bridge in 1976.

In July 1974 the Old Vic presented a rock concert for the first time. National Theatre director Peter Hall arranged for the progressive folk-rock band Gryphon to première Midnight Mushrumps, the fantasia inspired by Hall's own 1974 Old Vic production of The Tempest starring John Gielgud for which Gryphon had supplied the music.

Prospect Theatre Company

For two years prior to the departure of the National Theatre Company, Toby Robertson, director of the Prospect Theatre Company, sustained a campaign that the Old Vic should make Prospect its resident company.[20] For the Old Vic, Robertson's overtures proved increasingly hard to resist in the face of poor box office returns achieved by productions staged by other visiting companies; against this, Prospect staged a highly successful season which opened in May 1977, including Hamlet with Derek Jacobi, Antony and Cleopatra with Alec McCowen and Dorothy Tutin; and Saint Joan with Eileen Atkins.[21][22] In July the Governors of the Old Vic announced "a marriage that was all but a merger" between the Vic and Prospect. In September Toby Robertson, director of Prospect, was asked to take artistic control of the Old Vic, and Christopher Richards, general manager of the Old Vic, became general manager of Prospect.[23]

One major problem, though, was the terms of Prospect's funding by the Arts Council of Great Britain: this was on the basis of it being a touring company, and the council – already funding the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company in London – could not accept a case for another theatre company in the capital and repeatedly refused requests to fund any London seasons staged by Prospect. Therefore, any London-based productions would have to succeed financially without Arts Council support. Prospect's first season at the Old Vic recouped its costs but left no surplus to fund future productions. Further stagings by visiting companies were box office failures and stretched the theatre's finances to breaking point.[24] Yet Prospect continued to draw audiences to the Old Vic where other companies failed. In December 1978, the governors of the Old Vic agreed to a five-year contract with Prospect, announcing to the press on 23 April that henceforth they would be styled "Prospect Productions Ltd., trading as the Old Vic Company".[25] Unfortunately Prospect's touring commitments kept the company out of the theatre for the first half of 1979, leaving the theatre to sink further into debt. The company returned in July with Jacobi's Hamlet (toured afterwards to Denmark, Australia and China, the first English theatre company to tour that country),[26] followed by Romeo and Juliet, and The Government Inspector with Ian Richardson.[25] The following season, however, proved controversial: the proposed programming, including the double bill of The Padlock and Miss in Her Teens, to mark the bicentenary of David Garrick's death, and a revival of What the Butler Saw, were deemed by the Arts Council unsuitable for touring repertory.[25] An internal report by Prospect now questioned "whether Prospect can any longer satisfy the triple task of filling the Vic, of satisfying the Arts Council Director of Touring's requirements for product of a certain familiar sort, and of realising the vision of Toby Robertson".[27]

Robertson was in effect fired as artistic director in 1980 while he was abroad with the company in China, Timothy West replacing him.[28] The following season, West's first as Robertson's successor, saw Macbeth with Peter O'Toole, The Merchant of Venice with West as Shylock, and a gala performance presented to the Queen Mother to celebrate her eightieth birthday.[29] On 22 December 1980, four days after the gala performance, the Arts Council withdrew its funding from the company, sealing its inevitable demise.[26][29] The company gave a final season at the Old Vic in 1981, staging The Merchant of Venice, then gave a final tour of Europe, giving its last performance in Rome on 14 June before disbanding.[29]

Youth Theatre

The 'Old Vic Youth Theatre’ was an acting company for young people between the ages of 12 and 20 mainly from the London Borough of Southwark. The group was founded by Tom Vaughan of the Old Vic Theatre, Raymond Rivers of Morley College and Barry Anderson of the Southbank Education Institute. The Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) was the enterprise's main funding body.

During the early spring term of 1977 auditions consisting of improvisational scenes run by the Youth Theatre's first professional directors Lucy Parker and Frederick Proud took place and around 40 applicants were chosen to form the company.

By the middle of the summer in 1977 the 'Old Vic Youth Theatre’ had performed two plays for the paying public. First was ‘The Kitchen’ by Arnold Wesker which also incorporated improvised scenes alongside the actual script and was staged in the Emma Cons Hall at Morley College. The Youth Theatre's second production, ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ by William Shakespeare was first performed at the George Inn Courtyard as part of the Southwark Shakespeare Festival the same year and was the company's debut production at the Old Vic Theatre itself.

In the autumn of 1977 a new round of auditions took place and the existing group expanded into two. One group concentrated on a famous scripted play whilst the other would devise a play through improvisation from which the material was scripted into a play by a professional playwright.

The Youth groups continued to produce plays with new members auditioning each September until the mid 1980s.

Reopening

The Old Vic was significantly restored under the ownership of Toronto department-store entrepreneur 'Honest Ed' Mirvish in 1985. In 1987, his son David Mirvish installed Jonathan Miller as artistic director of the Old Vic and the theatre enjoyed several critical successes – including an Olivier Award for a production of the musical Candide, but suffered three straight years of financial loss. In 1990, Mirvish terminated Miller's contract over budgetary issues, earning much negative criticism in the British press.

In 1997, Mirvish appointed Sir Peter Hall as artistic director and, again, enjoyed critical acclaim with such productions as The Master Builder with Alan Bates and Waiting for Godot with Ben Kingsley, but continuing financial loss. Within a year of the appointment, Mirvish terminated Hall's contract – again to much negative comment in the press – and put the Old Vic up for sale. In 1998, the building was bought by a new charitable trust, the Old Vic Theatre Trust 2000. In 2000, the production company Criterion Productions was renamed Old Vic Productions plc, although relatively few of its productions are at the Old Vic theatre.

Kevin Spacey

In 2003, actor Kevin Spacey was appointed as new artistic director of the Old Vic Theatre Company. Spacey said he wanted to inject new life into the British theatre industry, and bring British and American theatrical talent to the stage. Spacey served as artistic director until 2015.

In November 2017, amid a series of rape and sexual misconduct allegations against Spacey, 20 people contacted the Old Vic with claims that he had sexually harassed or assaulted them at the theatre during his tenure as artistic director.[5][30] In the wake of the scandal, The Old Vic released a statement apologising for "not creating an environment or culture where people felt able to speak freely", and announced a "commitment to a new way forward".[31]

In 2018, the Old Vic announced that it had established the Guardians Programme, a group of trained staff who offer a confidential outlet for colleagues to share concerns about behaviour or the culture at work. Additionally, a Guardians Network has been formed to bring together the group of organisations from all sectors (not just the arts) who have implemented the principles of a Guardian Programme.[32]

Matthew Warchus

Since 2015, Matthew Warchus has been Artistic Director of The Old Vic.[33] His debut season opened in September 2015 with Warchus's production of a new play about education, Future Conditional by Tamsin Oglesby.

Bicentenary

On 24 October 2017, The Old Vic announced its bicentenary season.[34] The theatre celebrated its 200th birthday on 11 May 2018 with a free performance of Joe Penhall's Mood Music, featuring Ben Chaplin.[35]

Recent and current productions

2011 season

- Cause Célèbre by Terence Rattigan, directed by Thea Sharrock, starring Anne-Marie Duff

- Richard III by William Shakespeare, directed by Sam Mendes, starring Kevin Spacey

- The Playboy of the Western World by J M Synge, directed by John Crowley, starring Niamh Cusack, Ruth Negga and Robert Sheehan

- Noises Off by Michael Frayn, directed by Lindsay Posner

2012 season

- The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster, directed by Jamie Lloyd, starring Eve Best

- Democracy by Michael Frayn, directed by Paul Miller

- Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen in a new version by Brian Friel, directed by Anna Mackmin, starring Sheridan Smith

- Kiss Me, Kate music and lyrics by Cole Porter book by Sam and Bella Spewack, directed by Trevor Nunn, choreography by Stephen Mear, starring Alex Bourne, David Burt, Adam Garcia, Clive Rowe and Hannah Waddingham

2013 season

- The Winslow Boy by Terence Rattigan, directed by Lindsay Posner, starring Henry Goodman

- Sweet Bird of Youth by Tennessee Williams, directed by Marianne Elliott, starring Kim Cattrall and Seth Numrich

- Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare, directed by Mark Rylance, starring James Earl Jones and Vanessa Redgrave

- Fortune's Fool by Ivan Turgenev in a version by Mike Poulton, directed by Lucy Bailey, starring Richard McCabe

2014 season

- Other Desert Cities by Jon Robin Baitz, directed by Lindsay Posner

- Clarence Darrow by David W. Rintels, directed by Thea Sharrock, starring Kevin Spacey

- The Crucible by Arthur Miller, directed by Yaël Farber, starring Richard Armitage

- Electra by Sophocles in a version by Frank McGuinness, directed by Ian Rickson, starring Kristin Scott Thomas

2015 season

- Tree, a play for two people written and directed by Daniel Kitson, starring Tim Key and Daniel Kitson

- Clarence Darrow by David W. Rintels, directed by Thea Sharrock, starring Kevin Spacey

- High Society music and lyrics by Cole Porter book by Arthur Kopit, directed by Maria Friedman

2015–16 season

- Future Conditional by Tamsin Oglesby, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Rob Brydon

- The Hairy Ape by Eugene O'Neill, directed by Richard Jones, starring Bertie Carvel

- Dr. Seuss's The Lorax adapted for the stage by David Greig, music and lyrics by Charlie Fink, directed by Max Webster

- The Master Builder by Henrik Ibsen in a new adaptation by David Hare, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Ralph Fiennes

- The Caretaker by Harold Pinter, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Timothy Spall, Daniel Mays and George Mackay

- Jekyll & Hyde by The McOnie Company, devised directed and choreographed by Drew McOnie

- Groundhog Day book by Danny Rubin music and lyrics by Tim Minchin, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Andy Karl

2016–17 season

- No's Knife by Samuel Beckett, co-directed and performed by Lisa Dwan, co-directed by Joe Murphy

- King Lear by William Shakespeare, directed by Deborah Warner, starring Glenda Jackson (25 October-03 December 2016)

- Art by Yasmina Reza translated by Christopher Hampton, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Rufus Sewell, Tim Key and Paul Ritter (10 December 2016-18 February 2017)

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard, directed by David Leveaux, starring Daniel Radcliffe and Joshua McGuire (25 February-06 May 2017)

- Woyzeck by Georg Büchner in a new version by Jack Thorne, directed by Joe Murphy, starring John Boyega (15 May-24 June 2017)

- Girl from the North Country written and directed by Conor McPherson, music and lyrics by Bob Dylan

- Dr. Seuss's The Lorax adapted for the stage by David Greig, music and lyrics by Charlie Fink, directed by Max Webster

2017–18 season

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Rhys Ifans

- The Divide, a new play by Alan Ayckbourn, directed by Annabel Bolton

- Fanny and Alexander adapted for the stage by Stephen Beresford and starring Penelope Wilton[38]

- Mood Music by Joe Penhall and directed by Roger Michell[39] starring Ben Chaplin

- Bicentenary Variety Night

- Sea Wall by Simon Stephens, starring Andrew Scott (18 June-30 June 2018)

- A Monster Calls, based on the novel by Patrick Ness and inspired by an idea from Siobhan Dowd, devised by the company[40] (7 July-25 August 2018)

2018–19 season

- Sylvia written by Kate Prince and Priya Parma, with Prince providing choreography and direction as well[41] (03 September-22 September 2018)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Stephen Tompkinson

- The American Clock by Arthur Miller, directed by Rachel Chavkin (04 February-30 March 2019)

- All My Sons by Arthur Miller, directed by Jeremy Herrin, starring Sally Field, Bill Pullman, Jenna Coleman and Colin Morgan (13 April-08 June 2019)

- Present Laughter by Noël Coward, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Andrew Scott (17 June-10 August 2019)

2019–20 season

- A Very Expensive Poison by Lucy Prebble, based on the book by Luke Harding (20 August-05 October 2019)

- Lungs by Duncan Macmillan, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Matt Smith and Claire Foy (14 October-09 November 2019)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Paterson Joseph (23 November 2019-18 January 2020)

- Endgame (in double bill with Rough for Theatre II) by Samuel Beckett, directed by Richard Jones, starring Alan Cumming and Daniel Radcliffe (closed early due to the COVID-19 pandemic)

Old Vic: In Camera series (during COVID-19 pandemic)

- Lungs by Duncan Macmillan, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Matt Smith and Claire Foy (26 June-4 July 2020, Playback 27 January-29 January 2021)

- Three Kings by Stephen Beresford, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Andrew Scott (29 July-1 August 2020, Playback 2 December-4 December 2020)

- Faith Healer by Brian Friel, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Michael Sheen, David Threlfall and Indira Varma (16 September-19 September 2020, Playback 20 January-22 January 2021)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Andrew Lincoln (12 December-24 December 2020)

- Dr. Seuss's The Lorax adapted for the stage by David Greig, music and lyrics by Charlie Fink, directed by Max Webster, starring Jamael Westman and Audrey Brisson (14 April-17 April 2021, Playback 01 November-02 November 2021)

- The Dumb Waiter by Harold Pinter, directed by Jeremy Herrin, starring David Thewlis and Daniel Mays (07 July-10 July 2021, also with studio audience)

- Bagdad Cafe, adapted and directed by Emma Rice (25 August-28 August 2021, also with studio audience)

2021–22 season

- The Dumb Waiter by Harold Pinter, directed by Jeremy Herrin, starring David Thewlis and Daniel Mays

- Bagdad Cafe, adapted and directed by Emma Rice (17 July-21 August 2021)

- Camp Siegfried by Bess Wohl, directed by Katy Rudd, starring Patsy Ferran and Luke Thallon (07 September-30 October 2021)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Stephen Mangan (13 November 2021-08 January 2022)

- A Number by Caryl Churchill, directed by Lyndsey Turner, starring Paapa Essiedu and Lennie James (24 January-19 March 2022)

- The 47th by Mike Bartlett, directed by Rupert Goold, starring Bertie Carvel, Tamarie Tunie and Lydia Wilson (29 March-28 May 2022)

- Jitney by August Wilson, directed by Tinuke Craig, starring Will Johnson and Solomon Israel (09 June-09 July 2022)

2022–23 season

- Eureka Day by Jonathan Spector, directed by Katy Rudd, starring Helen Hunt (06 September-31 October 2022)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Owen Teale (12 November 2022-07 January 2023)

- Sylvia, by Kate Prince and Priya Parma, with music by Josh Cohen and DJ Walde, directed by Kate Prince, starring Beverley Knight (27 January-08 April 2023)

- Groundhog Day, by Danny Rubin and Tim Minchin, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Andy Karl (20 May-19 August 2023)

- Mog the Forgetful Cat, by The Wardrobe Ensemble, adapted from the novel by Judith Kerr, directed by Helena Middleton and Jesse Jones (11 July-29 July 2023)

2023–24 season

- Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw, directed by Richard Jones, starring Bertie Carvel and Patsy Ferran (26 September-28 October 2023)

- A Christmas Carol, a version by Jack Thorne, directed by Matthew Warchus, starring Christopher Eccleston (11 November 2023-06 January 2024)

- Just For One Day by John O'Farrell, directed by Luke Sheppard (26 January-30 March 2024)

References

- Historic England, "Old Vic Theatre (1068710)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 2 September 2020

- "Kenny, Sean, 1932–1973". National Art Library Catalogue. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - English Heritage listing details 28 April 2007

- "Spacey 'to run Old Vic'". BBC News. 3 February 2003. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Clarke, Stewart (16 November 2017). "Old Vic Theater Logs 20 Complaints About Kevin Spacey, Pledges to Improve Accountability". Variety. Los Angeles, California: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Brown, Mark (22 May 2014). "Matthew Warchus to take [Kevin Spacey's role running the Old Vic". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Frick, John W. (2003). Theatre, culture and temperance reform in nineteenth-century America. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-521-81778-3.

- Rowell, George Presbury (1993). The Old Vic Theatre: a history. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–29. ISBN 0-521-34625-8.

- "Royal Victoria Theatre". Standard. London. 2 July 1833.

- "Court Circular". The Times. London. 30 November 1833.

- Newton, Henry Chance (1923). The Old Vic. and its associations; being my own extraordinary experiences of "Queen Victoria's own theayter". London: Fleetway Press. OCLC 150444870.

- "7 things you never knew about the Old Vic Theatre". 10 May 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Coleman (2014), pp. 22–36.

- Coleman (2014), pp. 43–57.

- 'The Royal Victoria Hall –The Old Vic' Archived 20 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Survey of London: Vol. 23. Lambeth: South Bank and Vauxhall (1951), pp. 37–9. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- "Broadcasting the "Old Vic."". The Radio Times. No. 12. 14 December 1923. p. 410. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- "Wireless Programme - Saturday (Nov. 24th.)". The Radio Times. No. 8. 16 November 1923. p. 267. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Baylis, Lilian (12 October 1923). "The Romance of the 'Old Vic.'". The Radio Times. No. 3. p. 70. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- "Search Results for England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007". Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Rowell, p. 157

- Rowell, p. 158

- "History of the Old Vic, 1950–1999". The Old Vic. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Prospect Theatre Company". Ian McKellen Stage. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Rowell, p. 159

- Rowell, p. 160

- Hunter, Adriana (2006). "Prospect Theatre Company" in Continuum Companion to Twentieth Century Theatre. A&C Black. p. 623. ISBN 9781847140012. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Quoted in Rowell, p. 160

- Coveney, Michael (8 July 2012). "Toby Robertson obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- Rowell, p. 161

- "Kevin Spacey: Old Vic reveals 20 staff allegations against him". BBC. London, England. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Garrido, Duarte (16 November 2017). "Old Vic theatre apologises after Kevin Spacey investigation reveals 20 allegations". Sky News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- {{cite website=The Guardians Programme|date=21 May 2019|url=https://www.oldvictheatre.com/about-us/guardians-programme%7Ctitle=Guardian Programme}}

- "Matthew Warchus to take Kevin Spacey's role running the Old Vic". The Guardian. 22 May 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Old Vic announces bicentennial season | WhatsOnStage". Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "The Old Vic is giving out free tickets (And cake) for its birthday". 22 March 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Fiennes and Spall lead Old Vic season". www.officiallondontheatre.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Matthew Warchus unveils 2016/17 Old Vic Season". Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Fanny & Alexander Cast | The Old Vic". The Old Vic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Mood Music Cast | The Old Vic". The Old Vic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "A Monster Calls Cast | The Old Vic". The Old Vic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Sylvia Cast | The Old Vic". The Old Vic. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

Sources

- Coleman, Terry (2014). The Old Vic: The Story of a Great Theatre from Kean to Olivier to Spacey. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-31125-5.

- Rowell, George (1993). The Old Vic Theatre: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521346252.

Further reading

- Guide to British Theatres 1750–1950, John Earl and Michael Sell pp. 128–9 (Theatres Trust, 2000) ISBN 0-7136-5688-3