The Rockpile

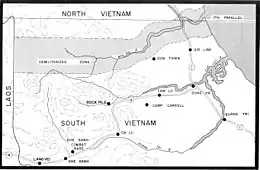

The Rockpile (also known as Elliot Combat Base) and known in Vietnamese as Núi Một, is a solitary karst rock outcropping north of Route 9 and south of the former Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Its relatively inaccessible location, reached only by helicopter, made it an important United States Army and US Marine Corps observation post and artillery base from 1966 to 1969.

| The Rockpile | |

|---|---|

| Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam | |

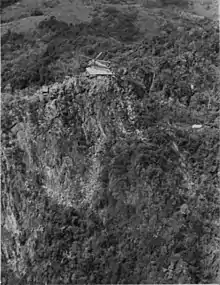

Photograph of the Rockpile and surrounding terrain from 2010 | |

| Coordinates | 16°46′49.82″N 106°51′7.37″E |

| Type | Marines |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1966 |

| In use | 1966–1973 |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | 3rd Marine Division, 1st Marine Division |

Geography

The Rockpile is located in Vietnam approximately 10 miles (16 km) from the southernmost boundary of the DMZ and 16 miles (26 km) west of Dong Ha. A Marine reconnaissance team described the cone shaped as a "toothpick-type mountain stuck out in the middle of an open area with a sheer cliff straight up and down".[1] The mountain rises almost 790 feet (240 m) from the Cam Lo River bottom and sits astride several major infiltration routes from North Vietnam and Laos. The visually dominating figure, which would come to be a familiar landmark for soldiers fighting the war for the DMZ, sits just one kilometer from the vital Route 9. Impressive as it was within the immediate vicinity, the Rockpile is overshadowed by other, much higher hills in nearly every direction. To the Rockpile's northwest is Dong Ke Soc mountain that stands at over 2,200 feet (670 m), to the direct north is Nui Cay Tri (later known as Mutter's Ridge after the radio call sign of the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines who would defend it), and to the northeast is Dong Ha Mountain.[2] Atop the Rockpile is a plateau-like summit that is 40 feet (12 m) long by 17 feet (5.2 m) across at its widest point.[3]

Strategic importance

The Rockpile was first observed and made note of by a small Marine reconnaissance team on 4 July 1966. The area later became a key outpost from which American and South Vietnamese forces could observe movements by the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and Viet Cong (VC) troops near the DMZ and in the central and west sectors of northern I Corps.[4]

The Rockpile is located at the junction of five major valleys less than 10 miles away from the hotly contested DMZ and held a commanding view over the surrounding area including several key infiltration routes.[5] The mountain's height made it ideal for observation as it was possible to see ships in the South China Sea approximately 20 miles (32 km) to the east, while what was called "Ghost Mountain" in Laos was visible to the west on a clear day.[6]

The hill's relative location to Route 9 gave the Rockpile an added significance. Route 9 runs parallel to the DMZ from Dong Ha, past the Rockpile, and on through Khe Sanh before becoming a dirt track that crosses the border into Laos.[7] In addition, its location gave the American forces an upper hand in the defense and supply of Khe Sanh Combat Base, Ca Lu Combat Base and Camp Carroll as it was possible to interdict potential ambushes along Route 9. Mountains positioned on either side of Route 9 near the Rockpile provided the PAVN/VC with excellent cover to mount any ambushes against allied convoys travelling through the area. For these reasons the United States high command decided to keep the Rockpile and the surrounding area as secure as possible for several years during the height of the conflict.[8] Ultimately, the United States' occupation of the Rockpile forced the PAVN/VC to use higher and more dangerous infiltration routes to the west closer to Laos because the normal routes through the Cam Lo and Dong Ha areas were essentially closed off.[9]

Operations

.jpg.webp)

When it was first observed in July 1966, there was still a large enemy force operating at the base and in the shadow of the Rockpile. The fight for the mountain occurred during Operation Hastings and involved 8,000 Marines and 3,000 South Vietnamese soldiers. The base at Dong Ha was used as a staging area to mount an attack on the DMZ and the area around the Rockpile. Brigadier General Lowell English, a commander in charge of Operation Hastings, stated that the Marines sought to take the North Vietnamese by surprise on their crucial infiltration routes and to smash and destroy their force in the DMZ region before they had a chance to regain balance or momentum. By the operation's end on 3 August 1966 the United States had accounted for at least 824 confirmed PAVN soldiers killed and 214 captured weapons compared to the 126 Marines killed and 448 wounded.[10] The Rockpile officially came under the control of American troops by the end of July 1966 when a small observation team landed on the summit. The PAVN immediately attempted to remove the Marines from their defensive position, but several attempts at scaling the Rockpile and striking the top and sides with mortar rounds proved ineffective. Operation Prairie swung the momentum for the mountain's fight after waves of Marines stormed into the area to reinforce the troops around the Rockpile and fortify its defenses.[9] From then on the Rockpile was often manned by at least a squad of United States Marines, who received supply drops by helicopters and would go on to launch numerous operations from the base of the mountain.[4]

The military officially named the camp Elliott Combat Base, but more often than not it was simply known as the Rockpile. The location seemed vulnerable to many of the soldiers that defended it due to its location in the center of an open valley, along a river, with elephant grass growing much closer to the perimeter of the base than most other camps located throughout northern South Vietnam. Once inside the barbed wire boundary, the congested and disorganized layout of the base area was immediately noticeable. Tents, low bunkers, and trenches commingled across the camp in no particular order or arrangement. The three largest tents at the Rockpile all possessed dirt floors with canvas sides and served as a kitchen, a mess hall, and a first-aid station. The dining tent had no chairs or tables, but instead long planks were positioned slightly over waist high so soldiers could stand and eat.[11]

Battalions stationed at the Rockpile also had the responsibility of maintaining an outpost on top of the peak as well. Generally a twenty man contingent, composed mostly of Army technicians, operated at the summit with sophisticated detection and communication equipment that monitored the DMZ. The summit could easily be defended against attack and was well within the capability of such a small group to repel any attempt to overtake the mountain. Typically the provisional Marine team, including an officer, was rotated every thirty days and became one of the most sought after positions in the DMZ as it was considered the safest place in the area due to its fortress-like pinnacle. In fact, many Marines regarded the Rockpile and Elliot Combat Base as the ideal location to be stationed because there was a high likelihood they would make it through their tour, which typically lasted from a week to two months at the base, unscathed. On top of the Rockpile was a large helicopter pad constructed from heavy timbers.[12] Most of the base's supplies were delivered via helicopter due to its relatively inaccessible location; however, pilots often had to abort landing because of heavy fog, intense rain, and winds exceeding fifty miles per hour.[9]

Just as Nui Cay Tri Mountain, or Mutter's Ridge, would be synonymous with the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, the Rockpile was consequently linked with the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines. The battalion was regularly stationed there and in charge of the mountain's defense for a majority of the fight for the DMZ.[7]

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Marine Corps.

- Olson, James S. (2008). In Country: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-4351-1184-4. OCLC 317495523., 495.

- Lehrack, Otto J. (1992). No Shining Armor: The Marines at War in Vietnam. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0533-9. OCLC 24846508., 104.

- Mahon, Ray. "Rockpile Marines don't take many hikes". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Olson, 495

- Mahon, "Rockpile Marines don't take many hikes"

- Brown, Jim (2004). Impact Zone: The Battle of the DMZ in Vietnam. Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1402-4. OCLC 54356555., 48

- Lehrack, 104

- Brown, 34

- Mahon, "Rockpile Marines Don't Take Many Hikes"

- Bartlett, Tom. "In the Shadow of the ROCKPILE". Marine Corps Association and Foundation. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Brown, 29

- Brown, 45-48

Further reading

- "The Rockpile". Time. October 7, 1966. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Jewett, Rus. "Gruntfixer: An accounting of my experiences as a Hospital Corpsman attached to "Ripley's Raiders" Lima Company 3rd Battalion 3rd Marines – 1967".