The Things that Live on Mars

"The Things that Live on Mars" is a 1908 non-fiction essay by English writer H. G. Wells, with four illustrations by American artist William Robinson Leigh, about the habitability and possibility of life on Mars, ideas that Wells had previously explored a decade earlier in his science fiction work The War of the Worlds (1898). "The Things that Live on Mars" was originally published in Cosmopolitan, in the same issue as "Story of the Mars Expedition", an essay by American astronomer David Peck Todd describing the 1907 Lowell expedition to Chile, an attempt to capture images of the purported Martian canals. Lowell's canals were later discredited and explained as an optical illusion in the early 20th century.[1][2]

| "The Things that Live on Mars" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by H. G. Wells | |

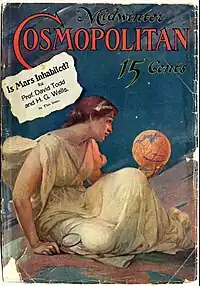

1908 cover by Frederick Lincoln Stoddard | |

| Original title | The Things that Live on Mars |

| Country | United States |

| Genre(s) | Essay |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Cosmopolitan |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Media type | Print (Magazine) |

| Publication date | March 1908 |

Development

Wells originally pursued his initial line of inquiry into the types of possible life that might be found on Mars while developing a science fiction story in the mid-1890s that would later become the novel The War of the Worlds (1898).[3] The work of astronomer Percival Lowell, founder of the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, captured the imagination of Wells, particularly his book Mars and Its Canals (1906), which promoted the idea of artificial Martian canals created by an advanced civilization on Mars, an idea that Wells found compelling, but was dismissed by the astronomical community as a fantasy.[1] Lowell's claims convinced Wells of not just the habitability of Mars, but also for the idea that "it is inhabited by creatures of sufficient energy and engineering science to make canals beside which our greatest human achievements pale into insignificance."[4] The many unanswered questions about these purported Martians led Wells to compose an essay to explore and take an "imaginative flight" into the speculative natural history of Mars, with descriptions of all its flora and fauna, and depictions of the Martians themselves.[5]

Synopsis

Wells tackles the speculative theory of life on Mars in a nine page essay, with four pages devoted to illustrations by William Robinson Leigh and five pages of prose split into a brief introduction and background to the subject, followed by eight sections: "Does life exist on Mars?", "Probable Appearance of the Martian Flora", "The Animal Kingdom", "No Fish on the Planet", "Climatic Conditions", "The Ruling Inhabitants", "How Like Terrestrial Humanity?", and "Martian Civilizations".

Illustrations

American artist William Robinson Leigh, known for his art depicting the American west and Southwestern United States, grew up reading natural history and honed his artistic skills drawing wildlife in West Virginia. When the essay was written, Leigh was a contract artist for popular magazines. Unlike his previous work with writers, Leigh collaborated with Wells in coming up with the design of the Martian landscape, civilization, and creatures which could conceivably inhabit the planet.[6] Historian Jennifer Tucker notes that Leigh's illustrations reflect a "sophisticated and innovative use of line and space, associated with new graphic design concepts in the early 1900s" with a "nod to modern symbols big and small", from the "iconography of world's fairs, monuments, and exhibitions to the fashionable dress and headband of the 'flapper' Martian girl". Leigh's images, Tucker writes, belong to the then nascent "visual genre of scientific realism", which was intended to express the current state of scientific knowledge, rather than as mere cartoons or as fine arts.[7]

"There are certain features in which they are likely to resemble us. And as likely as not they will be covered with feathers or fur. It is no less reasonable to suppose, instead of a hand, a group of tentacles or proboscis-like organs"[8]

"There are certain features in which they are likely to resemble us. And as likely as not they will be covered with feathers or fur. It is no less reasonable to suppose, instead of a hand, a group of tentacles or proboscis-like organs"[8] "A jungle of big, slender, stalky, lax-textured, flood-fed plants with a sort of insect life fluttering amidst the vegetation"[9]

"A jungle of big, slender, stalky, lax-textured, flood-fed plants with a sort of insect life fluttering amidst the vegetation"[9] "The same reason that will make the vegetation laxer and flimsier will make the forms of the Martian animal kingdom laxer and flimsier and either larger or else slenderer than Earthly types"[10]

"The same reason that will make the vegetation laxer and flimsier will make the forms of the Martian animal kingdom laxer and flimsier and either larger or else slenderer than Earthly types"[10] "Conditions on Mars are such that the inhabitants could utilize the direct energy of the sun's rays to drive machinery for filling the canals"[11]

"Conditions on Mars are such that the inhabitants could utilize the direct energy of the sun's rays to drive machinery for filling the canals"[11]

See also

- Edison's Conquest of Mars (1898)

- Is Mars Habitable? (1907)

- Star-Begotten (1937)

References

- Tucker 2013, pp. 211, 227-228.

- Crossley 2011 pp. 126-128; Brown 2005, pp. 315-326; Poulos 2018.

- Wells 1908, p. 335.

- Tucker 2013, p. 228; Wells 1908, p. 335.

- Wells 1908, p. 335-336.

- Tucker 2023, pp. 228-229.

- Tucker 2023, pp. 229-230.

- Wells 1908, p. 334.

- Wells 1908, p. 337.

- Wells 1908, p. 339.

- Wells 1908, p. 341.

Bibliography

- Brown, Michael (2005). "Phenomenology and Historical Research". In Ken Smith, Sandra Moriarty, Gretchen Barbatsis,and Keith Kenney (ed.) Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media (2011). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 9781410611581. OCLC 57249728.

- Crossley, Robert (2011). Imagining Mars: A Literary History. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 9780819569271. OCLC 767498449.

- Poulos, James (2018). "For the Love of Mars: Why settling the red planet can lift us from our antihuman malaise". In Stuart Clark (ed.) The Book of Mars: An Anthology of Fact and Fiction (2022). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781801109291. OCLC 1356622862.

- Tucker, Jennifer (2013). Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421413211. OCLC 855524855.

- Wells, H. G. & Leigh, W. R. (March 1908). "The Things that Live on Mars". Cosmopolitan. 44 (4): 334-342. OCLC 555452225.