Blind men and an elephant

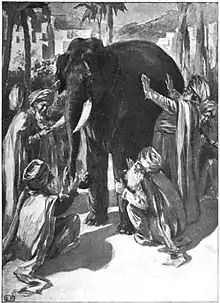

The parable of the blind men and an elephant is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn and imagine what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant's body, but only one part, such as the side or the tusk. They then describe the elephant based on their limited experience and their descriptions of the elephant are different from each other. In some versions, they come to suspect that the other person is dishonest and they come to blows. The moral of the parable is that humans have a tendency to claim absolute truth based on their limited, subjective experience as they ignore other people's limited, subjective experiences which may be equally true.[1][2] The parable originated in the ancient Indian subcontinent, from where it has been widely diffused.

The Buddhist text Tittha Sutta, Udāna 6.4, Khuddaka Nikaya,[3] contains one of the earliest versions of the story. The Tittha Sutta is dated to around c. 500 BCE, during the lifetime of the Buddha.[4] Other versions of the parable describes sighted men encountering a large statue on a dark night, or some other large object while blindfolded.

In its various versions, it is a parable that has crossed between many religious traditions and is part of Jain, Hindu and Buddhist texts of 1st millennium CE or before.[5][4] The story also appears in 2nd millennium Sufi and Baháʼí Faith lore. The tale later became well known in Europe, with 19th-century American poet John Godfrey Saxe creating his own version as a poem, with a final verse that explains that the elephant is a metaphor for God, and the various blind men represent religions that disagree on something no one has fully experienced.[6] The story has been published in many books for adults and children, and interpreted in a variety of ways.

The parable

The earliest versions of the parable of blind men and elephant is found in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain texts, as they discuss the limits of perception and the importance of complete context. The parable has several Indian variations, but broadly goes as follows:[7][2]

A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form. Out of curiosity, they said: "We must inspect and know it by touch, of which we are capable". So, they sought it out, and when they found it they groped about it. The first person, whose hand landed on the trunk, said, "This being is like a thick snake". For another one whose hand reached its ear, it seemed like a kind of fan. As for another person, whose hand was upon its leg, said, the elephant is a pillar like a tree-trunk. The blind man who placed his hand upon its side said the elephant, "is a wall". Another who felt its tail, described it as a rope. The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth and like a spear.

In some versions, the blind men then discover their disagreements, suspect the others to be not telling the truth and come to blows. The stories also differ primarily in how the elephant's body parts are described, how violent the conflict becomes and how (or if) the conflict among the men and their perspectives is resolved. In some versions, they stop talking, start listening and collaborate to "see" the full elephant. In another, a sighted man enters the parable and describes the entire elephant from various perspectives, the blind men then learn that they were all partially correct and partially wrong. While one's subjective experience is true, it may not be the totality of truth.[4][7]

The parable has been used to illustrate a range of truths and fallacies; broadly, the parable implies that one's subjective experience can be true, but that such experience is inherently limited by its failure to account for other truths or a totality of truth. At various times the parable has provided insight into the relativism, opaqueness or inexpressible nature of truth, the behavior of experts in fields of contradicting theories, the need for deeper understanding, and respect for different perspectives on the same object of observation. In this respect, it provides an easily understood and practical example that illustrates ontologic reasoning. That is, simply put, what things exist, what is their true nature, and how can their relations to each other be accurately categorized? For example, is the elephant's trunk a snake, or its legs trees, just because they share some similarities with those? Or is that just a misapprehension that differs from an underlying reality? And how should human beings treat each other as they strive to understand better (anger, respect, tolerance or intolerance)?

Hinduism

(wall relief in Northeast Thailand)

The Rigveda, dated to have been written down (from earlier oral traditions) between 1500 and 1200 BCE, states "Reality is one, though wise men speak of it variously." According to Paul J. Griffiths, this premise is the foundation of universalist perspective behind the parable of the blind men and an elephant. The hymn asserts that the same reality is subject to interpretations and described in various ways by the wise.[5] In the oldest version, four blind men walk into a forest where they meet an elephant. In this version, they do not fight with each other, but conclude that they each must have perceived a different beast although they experienced the same elephant.[5] The expanded version of the parable occurs in various ancient and Hindu texts. Many scholars refer to it as a Hindu parable.[7][2][8]

The parable or references appear in bhasya (commentaries, secondary literature) in the Hindu traditions. For example, Adi Shankara mentions it in his bhasya on verse 5.18.1 of the Chandogya Upanishad as follows:

etaddhasti darshana iva jatyandhah

Translation: That is like people blind by birth in/when viewing an elephant.

— Adi Shankara, Translator: Hans Henrich Hock[9]

Jainism

The medieval era Jain texts explain the concepts of anekāntavāda (or "many-sidedness") and syādvāda ("conditioned viewpoints") with the parable of the blind men and an elephant (Andhgajanyāyah), which addresses the manifold nature of truth. This parable is found in the most ancient Jain agams before 5th century BCE. Its popularity remained till late. For example, this parable is found in Tattvarthaslokavatika of Vidyanandi (9th century) and Syādvādamanjari of Ācārya Mallisena (13th century). Mallisena uses the parable to argue that immature people deny various aspects of truth; deluded by the aspects they do understand, they deny the aspects they don't understand. "Due to extreme delusion produced on account of a partial viewpoint, the immature deny one aspect and try to establish another. This is the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant."[10] Mallisena also cites the parable when noting the importance of considering all viewpoints in obtaining a full picture of reality. "It is impossible to properly understand an entity consisting of infinite properties without the method of modal description consisting of all viewpoints, since it will otherwise lead to a situation of seizing mere sprouts (i.e., a superficial, inadequate cognition), on the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant."[11]

Buddhism

The Buddha twice uses the simile of blind men led astray. The earliest known version was recorded in the one of Buddhist scriptures, known as Tittha Sutta.[3]

In another scripture known as Canki Sutta, the Buddha describes a row of blind men holding on to each other as an example of those who follow an old text that has passed down from generation to generation.[12] In the Udana (68–69)[13] he uses the elephant parable to describe sectarian quarrels. A king invited a group of blind men in the capital to be brought to the palace, where an elephant is brought in and they are asked to describe it.

When the blind men had each felt a part of the elephant, the king went to each of them and said to each: "Well, blind man, have you seen the elephant? Tell me, what sort of thing is an elephant?"

The men assert the elephant is either like a pot (the blind man who felt the elephant's head), a winnowing basket (ear), a plowshare (tusk), a plow (trunk), a granary (body), a pillar (foot), a mortar (back), a pestle (tail) or a brush (tip of the tail).

The men cannot agree with one another and come to blows over the question of what it is like and their dispute delights the king. The Buddha ends the story by comparing the blind men to preachers and scholars who are blind and ignorant and hold to their own views: "Just so are these preachers and scholars holding various views blind and unseeing.... In their ignorance they are by nature quarrelsome, wrangling, and disputatious, each maintaining reality is thus and thus." The Buddha then speaks the following verse:

O how they cling and wrangle, some who claim

For preacher and monk the honored name!

For, quarreling, each to his view they cling.

Such folk see only one side of a thing.[14]

Sufism

The Persian Sufi poet Sanai (1080–1131/1141 CE) of Ghazni (currently, Afghanistan) presented this teaching story in his The Walled Garden of Truth.[15]

Rumi, the 13th Century Persian poet and teacher of Sufism, included it in his Masnavi. In his retelling, "The Elephant in the Dark", some Hindus bring an elephant to be exhibited in a dark room. A number of men touch and feel the elephant in the dark and, depending upon where they touch it, they believe the elephant to be like a water spout (trunk), a fan (ear), a pillar (leg) and a throne (back). Rumi uses this story as an example of the limits of individual perception:

The sensual eye is just like the palm of the hand. The palm has not the means of covering the whole of the beast.[16]

Rumi does not present a resolution to the conflict in his version, but states:

The eye of the Sea is one thing and the foam another. Let the foam go, and gaze with the eye of the Sea. Day and night foam-flecks are flung from the sea: oh amazing! You behold the foam but not the Sea. We are like boats dashing together; our eyes are darkened, yet we are in clear water.[16]

Rumi ends his poem by stating "If each had a candle and they went in together the differences would disappear."[17]

John Godfrey Saxe

One of the most famous versions of the 19th century was the poem "The Blind Men and the Elephant" by John Godfrey Saxe (1816–1887).

The poem begins:

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind[18]

Each in his own opinion concludes that the elephant is like a wall, snake, spear, tree, fan or rope, depending upon where they had touched. Their heated debate comes short of physical violence, but the conflict is never resolved.

Moral:

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!

Natalie Merchant sang this poem in full on her Leave Your Sleep album.

The meaning as proverb by language or domain

Japanese

In Japanese, the proverb is used as a simile of circumstance that ordinary men often fail to understand a great man or his great work.[19]

Chinese

In Chinese, the proverb means failure to see the whole picture e.g. due to improper generalization. [20]

Modern treatments

The story is seen as a metaphor in many disciplines, being pressed into service as an analogy in fields well beyond the traditional. In physics, it has been seen as an analogy for the wave–particle duality.[21] In biology, the way the blind men hold onto different parts of the elephant has been seen as a good analogy for the polyclonal B cell response.[22]

The fable is one of a number of tales that cast light on the response of hearers or readers to the story itself. Idries Shah has commented on this element of self-reference in the many interpretations of the story, and its function as a teaching story:

...people address themselves to this story in one or more [...] interpretations. They then accept or reject them. Now they can feel happy; they have arrived at an opinion about the matter. According to their conditioning they produce the answer. Now look at their answers. Some will say that this is a fascinating and touching allegory of the presence of God. Others will say that it is showing people how stupid mankind can be. Some say it is anti-scholastic. Others that it is just a tale copied by Rumi from Sanai – and so on.[24]

Shah adapted the tale in his book The Dermis Probe. This version begins with a conference of scientists, from different fields of expertise, presenting their conflicting conclusions on the material upon which a camera is focused. As the camera slowly zooms out it gradually becomes clear that the material under examination is the hide of an African elephant. The words 'The Parts Are Greater Than The Whole' then appear on the screen. This retelling formed the script for a short four-minute film by the animator Richard Williams. The film was chosen as an Outstanding Film of the Year and was exhibited at the London and New York film festivals.[25][26]

The Russian preface to a collection of Lewis Carroll's works (including such books as A Tangled Tale) includes the story as an analogy to the impression one gets from reading a few articles about Carroll, with him only being seen as a writer and poet by some, and a mediocre mathematician by others. The full picture, however, is that "Carroll only resembles Carroll the way an elephant only resembles an elephant".[27]

The story enjoys a continuing appeal, as shown by the number of illustrated children's books of the fable; there is one for instance by Paul Galdone and another, Seven Blind Mice, by Ed Young (1992).

In the title cartoon of one of his books, cartoonist Sam Gross postulated that one of the blind men, encountering a pile of the elephant feces, concluded that "An elephant is soft and mushy."

An elephant joke inverts the story in the following way, with the act of observation severely and fatally altering the subject of investigation:

Six blind elephants were discussing what men were like. After arguing they decided to find one and determine what it was like by direct experience. The first blind elephant felt the man and declared, 'Men are flat.' After the other blind elephants felt the man, they agreed.

Moral:

We have to remember that what we observe is not nature in itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.

Touching the Elephant was a 1997 BBC Radio 4 documentary in which four people of varying ages, all blind from birth, were brought to London Zoo to touch an elephant and describe their response.[29][30][31][32]

Ship of Theseus, a 2012 Indian philosophical drama named after the eponymous thought experiment, also references the parable.

See also

- Allegory of the cave, a rough equivalent in Western philosophy

- Anekantavada

- Black cat analogy

- Dispersed knowledge

- Duck test

- Elephant in the room

- Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, an 1884 satirical novella

- Hasty generalization

- Naïve realism (psychology)

- Rashomon effect – Unreliability of eyewitnesses

- Seeing pink elephants – Euphemism for drunken hallucination caused by alcoholic hallucinosis or delirium tremens

- Seeing the elephant – American figure of speech

- Syncretism – Assimilation of two or more originally discrete religious traditions

- The blind leading the blind

- The Country of the Blind

- Tittha Sutta (From Udāna)

- Unreliable narrator

References

- E. Bruce Goldstein (2010). Encyclopedia of Perception. SAGE Publications. p. 492. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8., Quote: The ancient Hindu parable of the six blind men and the elephant...."

- C.R. Snyder; Carol E. Ford (2013). Coping with Negative Life Events: Clinical and Social Psychological Perspectives. Springer Science. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4757-9865-4.

- "Ud 6:4 Sectarians (1) (Tittha Sutta)". suttacentral.net. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

This site offers a non-sectarian correspondence index of early Buddhist texts in all available language recensions, with multiple translations.

- John D. Ireland (2007). Udana and the Itivuttaka: Two Classics from the Pali Canon. Buddhist Publication Society. pp. 9, 81–84. ISBN 978-955-24-0164-0.

- Paul J. Griffiths (2007). An Apology for Apologetics: A Study in the Logic of Interreligious Dialogue. Wipf and Stock. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1-55635-731-2.

- Martin Gardner (1 September 1995). Famous Poems from Bygone Days. Courier Dover Publications. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-486-28623-5. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- E. Bruce Goldstein (2010). Encyclopedia of Perception. SAGE Publications. p. 492. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8.

- [a] Chad Meister (2016). Philosophy of Religion. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-137-31475-8.;

[b] Jeremy P. Shapiro; Robert D. Friedberg; Karen K. Bardenstein (2006). Child and Adolescent Therapy: Science and Art. Wiley. pp. 269, 314. ISBN 978-0-471-38637-7.;

[c] Peter B. Clarke; Peter Beyer (2009). The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. pp. 470–471. ISBN 978-1-135-21100-4. - Hans H Hock (2005). Edwin Francis Bryant; Laurie L. Patton (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Routledge. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-7007-1463-6.

- Mallisena, Syādvādamanjari, 14:103–104. Dhruva, A.B. (1933) pp. 9–10.

- Mallisena, Syādvādamanjari, 19:75–77. Dhruva, A.B. (1933) pp. 23–25.

- Accesstoinsight.org Archived 28 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Katinkahesselink.net

- Wang, Randy. "The Blind Men and the Elephant". Archived from the original on 2006-08-25. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

- Included in Idries Shah, Tales of the Dervishes ISBN 0-900860-47-2 Octagon Press 1993.

- Arberry, A.J. (2004-05-09). "71 – The Elephant in the dark, on the reconciliation of contrarieties". Rumi – Tales from Masnavi. Retrieved 2006-08-29.

- For an adaptation of Rumi's poem, see this song version by David Wilcox here Archived 9 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- Saxe, John Godfrey. . The poems of John Godfrey Saxe. p. – via Wikisource. [scan

]

] - "群盲象を評す". 日本国語大辞典. 20 April 2001. p. 1188. ISBN 4-09-521004-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "瞎子摸象 [修訂本參考資料] - 成語檢視 - 教育部《成語典》2020 [基礎版]". dict.idioms.moe.edu.tw (in Chinese). National Academy for Educational Research. Ministry of Education, Taiwan. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- For example, Quantum theory by David Bohm, p. 26. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- See for instance The lymph node in HIV pathogenesis by Michael M. Lederman and Leonid Margolis, Seminars in Immunology, Volume 20, Issue 3, June 2008, pp. 187–195.

- Holton, Martha Adelaide; Curry, Charles Madison (1914). Holton-Curry readers. University of California. Rand McNally & Co.

- Shah, Idries. "The Teaching Story: Observations on the Folklore of Our "Modern" Thought". Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- Octagon Press page for The Dermis Probe Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, with preview of story

- "touching the elephant". The Rockethouse. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Кэрролл, Льюис (15 January 2021). История с узелками, или Все не так, как кажется (сборник) [The Story with Knots, or Everything Is Not As It seems (compilation)] (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 9785040691340.

- Heisenberg, Werner (1958). Physics and philosophy: the revolution in modern science. Harper. p. 58. ISBN 9780140228595.

- "BBC Radio 4 Extra - 90 by 90 The Full Set, 1998: Touching The Elephant". BBC Online. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Elmes, Simon (10 November 2009). And Now on Radio 4: A Celebration of the World's Best Radio Station. Random House. p. 143. ISBN 9781407005287. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Hanks, Robert (3 January 1998). "Radio Review". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Gaisford, Sue (19 April 1997). "Radio: Tony, John and Paddy: get thee to a nunnery". The Independent. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

External links

- Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi. . Masnavi I Ma'navi. Translated by Edward Henry Whinfield – via Wikisource.

- Story of the Blind Men and the Elephant from www.spiritual-education.org

- All of Saxe's Poems including original printing of The Blindman and the Elephant Free to read and full text search.

- Buddhist Version as found in Jainism and Buddhism. Udana hosted by the University of Princeton

- Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi's version as translated by A.J. Arberry

- Jainist Version hosted by Jainworld

- John Godfrey Saxe's version hosted at Rice University