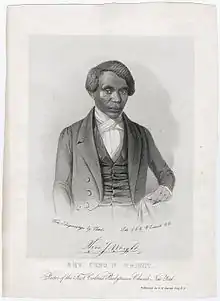

Theodore S. Wright

Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1797–1847), sometimes Theodore Sedgewick Wright, was an African-American abolitionist and minister who was active in New York City, where he led the First Colored Presbyterian Church as its second pastor. He was the first African American to attend Princeton Theological Seminary (and any United States theological seminary), from which he graduated in 1828 or 1829.[1] In 1833 he became a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial group that included Samuel Cornish, a Black Presbyterian, and many Congregationalists, and served on its executive committee until 1840.

Theodore S. Wright | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1797 |

| Died | 1847 |

Wright founded and helped develop the American Anti-slavery Society, the Union Missionary Society, and the American Missionary Association. Wright was a prominent activist, and in contributing to these organizations gave frequent speeches and was successful in his endeavors, contributing greatly to the anti-slave movement. At age 50, Wright died from possible exhaustion. He was an influential person who was passionate about the development of youth, first-rate education, spreading the gospel, and abolishing slavery.

Early life and education

Theodore Sedgwick Wright was born about 1797 to free parents in Providence, Rhode Island. He is believed to have moved into New York City with his family, where he attended the African Free School.[2] At the age of 28, he was admitted to American Institute of higher learning, becoming the second man of color ever to be admitted to the institute.

With the aid of Governor DeWitt Clinton and Arthur Tappan of the New York Manumission Society, and men from Princeton Theological Seminary, Wright was aided in his studies at the graduate seminary.[2] He described his time at the seminary as a "dark and gloomy period"[3] for race relations, in which the white faculty and students were united behind the American Colonization Society's efforts to remove free Black and enslaved Black Americans to Liberia. When John Brown Russwurm in Freedom's Journal combatted Wright's professor Archibald Alexander's support of colonization, Wright said the "united views and intentions of the people of color were made known, and the nation awoke as from slumber".[3] In 1829, Wright was the first African American to graduate from the seminary, and the first to complete theological studies at any seminary in the United States.[2]

Career

Before 1833, Wright was called as the second minister of New York's First Colored Presbyterian Church and served there the rest of his life. (It was later known as Shiloh Presbyterian Church and the successor congregation is now St. James Presbyterian Church in Harlem.[4]) He followed the founder, Samuel Cornish.

In 1833 Wright was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which had an interracial membership and leadership. He served on the executive committee until 1840. That year he left with other moderate members, including Arthur and Lewis Tappan, and helped found the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. They disagreed with some of William Lloyd Garrison's proposals, including his insistence on having women in leadership positions.[2]

In 1837, at a national Colored Convention, Wright opposed a resolution advocating black self-defense as "un-Christian." Wright supported activities of other black communities in the state; for instance, in 1837 he spoke at the dedication of the First Free Church of Schenectady, the first black church in the city, and praised its founding a school for its children.[5]

For years Wright acted as a conductor for the Underground Railroad in New York City and used his house at 235 W. Broadway as a station.[6] He served on New York's Committee of Vigilance, established to try to help fugitive slaves evade slave catchers and resist their being returned to the South.[6]

Later years

By 1843 Wright had changed his views on violent rebellion to end slavery. At that year's National Negro Convention in Buffalo, he supported Henry Highland Garnet's call for a slave uprising. His proposal was opposed by Frederick Douglass and narrowly defeated by the members of the convention.[2]

Marriage and family

In 1837 Wright married Adaline T. Turpin from New Rochelle, New York. On March 25, 1847, Theodore Sedgwick Wright died in New York City.

Wright at Princeton Theological Seminary in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The only book-length work on Wright is the 2005 Princeton Theological Seminary master's thesis by Daniel Paul Morrison. Titled, Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1794-1847): Early Princeton Theological Seminary Abolitionist, the theses reconstructs the biography of the man and offers insight into Wright struggle with the faculty of Princeton Seminary and the American Colonization Society which all of the faculty supported.[7] Morrison's work was cited in James H. Moorhead's 2012 Princeton Theological Seminary in American Religion and Culture.

In October 2021, as part of a "multi-year action plan to repent for [its] historical ties to slavery," Princeton Theological Seminary renamed its library the Theodore Sedgwick Wright Library.[8]

References

- Year with American Saints. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9780898697988.

- "Theodore Sedgwick Wright", Black Past, accessed May 31, 2012

- James, Winston (2010). The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-0-8147-4289-1.

- "Shiloh Presbyterian Church", Mapping African-American Places (MAAP), Columbia University, accessed May 31, 2012

- Theodore Sedgwick Wright, "Speech given during the dedication of the First Free Church of Schenectady, 28 December 1837", Emancipator, at University of Detroit Mercy, accessed May 31, 2012

- “Theodore Wright House”, Mapping African-American Places (MAAP), Columbia University, accessed May 31, 2012

- "Summon 2.0".

- "Princeton Seminary Names Library After Theodore Sedgwick Wright". October 13, 2021.

Further reading

- Rayford W. Logan and Michael R. Winston, eds., Dictionary of American Negro Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982)

- Bertram Wyatt-Brown, “American Abolitionism and Religion”, National Humanities Center.

External links

- "Theodore S. Wright", Black Abolitionist Archive, at University of Detroit Mercy; contains texts of numerous published speeches