Cod Wars

The Cod Wars (Icelandic: Þorskastríðin; also known as Landhelgisstríðin, lit. 'The Coastal Wars'; German: Kabeljaukriege) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Each of the disputes ended with an Icelandic victory.[1][2]

Some Icelandic historians view the history of Iceland's struggle for control of its maritime resources in ten episodes, or ten cod wars.[3] Fishing boats from Britain have been sailing to waters near Iceland in search of their catch since the 14th century. Agreements struck during the 15th century started a centuries-long series of intermittent disputes between the two countries. Demand for seafood and consequent competition for fish stocks grew rapidly in the 19th century.

The modern disputes or wars began in 1952 after Iceland expanded its territorial waters from 3 to 4 nautical miles (7 kilometres) based on a decision by the International Court of Justice. The United Kingdom responded by banning Icelandic ships landing their fish in British ports.[4] In 1958, after a United Nations conference at which several countries sought to extend the limits of their territorial waters to 12 nmi (22 km) at which no agreement was reached, Iceland unilaterally expanded its territorial waters to this limit and banned foreign fleets from fishing in these waters. Britain refused to accept this decision.[5] This led to a modern series of confrontations with the United Kingdom and other western European countries that took place in three stages over 20 years: 1958–1961, 1972–73 and 1975–76. A threat of damage and danger to life was present, with British fishing boats escorted to the fishing grounds by the Royal Navy while the Icelandic Coast Guard attempted to chase them away and use long hawsers to cut nets from the British boats; ships from both sides suffered damage from ramming attacks.

Each confrontation concluded with an agreement favourable for Iceland. Iceland made threats it would withdraw from NATO, which would have forfeited NATO's access to most of the GIUK gap, a critical anti-submarine warfare chokepoint during the Cold War. In a NATO-brokered agreement in 1976, the United Kingdom accepted Iceland's establishment of a 12-nautical-mile (22 km) exclusive zone around its shores where only its own ships could fish and a 200-nautical-mile (370-kilometre) Icelandic fishery zone where other nations' fishing fleets needed Iceland's permission. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters. As a result, British fishing communities lost access to rich areas and were devastated, with thousands of jobs lost.[6][7] The UK abandoned its "open seas" international fisheries policy and declared a similar 200-nautical-mile zone around its own waters. Since 1982, a 200-nautical-mile (370-kilometre) exclusive economic zone has been the international standard under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The term "cod war" was coined by a British journalist in early September 1958.[8] None of the Cod Wars meet any of the common thresholds for a conventional war,[lower-alpha 1] and they may more accurately be described as militarised interstate disputes.[10][11][12][13] There is only one confirmed death during the Cod Wars: an Icelandic engineer, who was accidentally killed in the Second Cod War while he was repairing damage on the Icelandic patrol boat Ægir after a collision with the British frigate Apollo. They collided on 29 August 1973.[14] A trawlerman from Grimsby was seriously wounded on 19 February 1976, hit by the loose cordage after an Icelandic gunboat cut his vessel's net.[15]

Several explanations for the Cod Wars have been put forward.[1][10] Recent studies have focused on the underlying economic, legal and strategic drivers for Iceland and the United Kingdom, as well as the domestic and international factors that contributed to the escalation of the dispute.[10][16] Lessons drawn from the Cod Wars have been applied to international relations theory.[10][16][17]

Background

Seafood has for centuries been a staple in the diet of inhabitants of the British Isles, Iceland and other Nordic countries, which are surrounded by some of the world's richest fisheries.[18] Danish and Norse raiders came to Britain in the ninth century bringing one fish species in particular, the North Sea cod, into the national diet. Other whitefish like halibut, hake and pollock also became popular.[19]

Until 1949

By the end of the 14th century, fishing boats from the east coast of England, then as now home to most of the English fishing fleet, were sailing to Icelandic waters in search of these catches; their landings grew so abundant as to cause political friction between England and Denmark, who ruled Iceland at the time. The Danish King Eric banned all Icelandic trade with England in 1414 and complained to his English counterpart, Henry V, about the depletion of fishing stocks off the island. Restrictions on British fishing passed by Parliament were generally ignored and unenforced, leading to violence and the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1469–1474). Diplomats resolved these disputes through agreements that allowed British ships to fish Icelandic waters with seven-year licences, a provision that was struck from the Treaty of Utrecht when it was presented to the Icelandic Althing for ratification in 1474.[20] This started a centuries-long series of intermittent disputes between the two countries.[21] From the early 16th century onward, English sailors and fishermen were a major presence in the waters off Iceland.[3][22]

With the increases in range of fishing that were enabled by steam power in the late 19th century, boat owners and skippers felt pressure to exploit new grounds. Their large catches in Icelandic waters attracted more regular voyages across the North Atlantic. In 1893, the Danish government, which then governed Iceland and the Faroe Islands, claimed a fishing limit of 50 nmi (93 km) around their shores. British trawler owners disputed the claim and continued to send their ships to the waters near Iceland. The British government did not recognise the Danish claim on the grounds that setting such a precedent would lead to similar claims by the nations around the North Sea, which would damage the British fishing industry.

In 1896, the United Kingdom made an agreement with Denmark for British vessels to use any Icelandic port for shelter if they stowed their gear and trawl nets. In return, British vessels were not to fish in Faxa Bay east of a line from Ílunýpa, a promontory near Keflavík to Þormóðssker (43.43° N, 22.30° W).

With many British trawlers being charged and fined by Danish gunboats for fishing illegally within the 13 nmi (24 km) limit, which the British government refused to recognise, the British press began to enquire why the Danish action against British interests was allowed to continue without intervention by the Royal Navy. The British made a show of naval force (gunboat diplomacy) in 1896 and 1897.[23]

In April 1899, the steam trawler Caspian was fishing off the Faroe Islands when a Danish gunboat tried to arrest her for allegedly fishing illegally inside the limits. The trawler refused to stop and was fired upon first with blank shells and then with live ammunition. Eventually, the trawler was caught, but before the skipper, Charles Henry Johnson, left his ship to go aboard the Danish gunboat, he ordered the mate to make a dash for it after he went on to the Danish ship. The Caspian set off at full speed. The gunboat fired several shots at the unarmed boat but could not catch up with the trawler, which returned, heavily damaged, to Grimsby, England. On board the Danish gunboat, the skipper of the Caspian was lashed to the mast. A court held at Thorshavn convicted him on several counts including illegal fishing and attempted assault, and he was jailed for 30 days.[24]

The 'Anglo-Danish Territorial Waters Agreement' of 1901 set a 3 nmi (6 km) territorial waters limit, measured narrowly, around each party's coastlines: this applied to Iceland as (at the time) part of Denmark and had a term of 50 years.[23][5]

The Icelandic fisheries grew in importance for the British fishing industry around the end of the 19th century.[23] The reduction in fishing activity brought about by the hostilities of the First World War effectively ended the dispute for a time.

While data is incomplete for the prewar period, one historian argues that the Icelandic fishing grounds were 'very important' to the British fishing industry as a whole.[25] Data from 1919 to 1938 showed a significant increase in the British total catches in Icelandic waters.[26] The British catches in Iceland were more than twice the combined catches of all other grounds of the British distant water fleet.[27] Icelanders grew increasingly dismayed at the British presence.[28]

1949–1958

In October 1949, Iceland initiated the two-year abrogation process of the agreement made between Denmark and the United Kingdom in 1901. The fishery limits to the north of Iceland were extended to 4 nmi (7 km). However, since the British trawling fleet did not use those grounds, the northern extension was not a source of significant contention between the two states. Initially planning to extend the rest of its fishery limits by the end of the two-year abrogation period, Iceland chose to postpone its extension to wait for the outcome of the UK–Norway fisheries case in the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which was decided in December 1951.

Icelanders were satisfied with the ICJ ruling, as they believed that Iceland's preferred extensions were similar to those afforded to Norway in the ICJ ruling. The UK and Iceland tried to negotiate a solution but were unable to reach agreement. The Icelandic government declared, on 19 March 1952, its intention to extend its fishery limits on 15 May 1952.[29]

Iceland and the United Kingdom were involved in a dispute from May 1952 to November 1956 over Iceland's unilateral extension of its fishery limits from 3 to 4 nmi (6 to 7 km). Unlike in the Cod Wars, the Royal Navy was never sent into Icelandic waters. The British trawling industry, however, implemented costly sanctions on Iceland by imposing a landing ban on Icelandic fish in British ports.[29][6] The landing ban was a major blow to the Icelandic fishing industry (the UK was Iceland's largest export market for fish) and caused consternation among Icelandic statesmen.[30][31] The two sides decided to refer one part of the Icelandic extension to the ICJ in early 1953: the controversial Faxa Bay delimitation.[29]

In May 1953, businessman George Dawson signed an agreement with the Icelandic trawler owners to buy fish landed in Britain. Seven landings were made but the merchants who bought from Dawson were blacklisted and he was unable to distribute the fish effectively himself.[32]

Cold War politics proved favourable for Iceland, as the Soviet Union, seeking influence in Iceland, stepped in to purchase Icelandic fish. The United States, fearing greater Soviet influence in Iceland, also did so and persuaded Spain and Italy to do likewise.[33][23]

Soviet and American involvement resulted in weakening the punitive effects of the British landing ban. Some scholars refer to the dispute of 1952 to 1956 as one of the Cod Wars, as the object of the dispute and its costs and risks were all similar to those in the other three Cod Wars.[34][35][36]

Just as the other Cod Wars, the dispute ended with Iceland achieving its aims, as the Icelandic 4 nmi (7 km) fishery limits were recognized by the United Kingdom, following a decision by the Organisation of European Economic Co-operation in 1956.[29]

Two years later, in 1958, the United Nations convened the first International Conference on the Law of the Sea, which was attended by 86 states.[37] Several countries sought to extend the limits of their territorial waters to 12 nmi (22 km), but the conference did not reach any firm conclusions.[38][39]

First Cod War (1958–1961)

| First Cod War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

Coventry City and ICGV Albert off the Westfjords | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| States involved | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| None | |||||||||

| a 3 by February 1960. | |||||||||

The First Cod War lasted from 1 September 1958 to 11 March 1961.[40][23] It began as soon as a new Icelandic law came into force and expanded the Icelandic fishery zone from 4 to 12 nautical miles (7.4 to 22.2 km) at midnight on 1 September 1958.

All members of NATO opposed the unilateral Icelandic extension.[45] The British declared that their trawlers would fish under protection from their warships in three areas: out of the Westfjords, north of Horn and southeast of Iceland. In all, twenty British trawlers, four warships and a supply vessel were inside the newly declared zones. The deployment was expensive; in February 1960, Lord Carrington, the First Lord of the Admiralty, responsible for the Royal Navy, stated that the ships near Iceland had expended half a million pounds sterling worth of oil since the new year and that a total of 53 British warships had taken part in the operations.[46] Against that, Iceland could deploy seven patrol vessels[47] and a single PBY-6A Catalina flying boat.[48]

The deployment of the Royal Navy to contested waters led to protests in Iceland. Demonstrations against the British embassy were met with taunts by the British ambassador, Andrew Gilchrist, as he played bagpipe music and military marches on his gramophone.[49] Many incidents followed. The Icelanders were, however, at a disadvantage in patrolling the contested waters because of the size of the area and the limited number of patrol ships. According to one historian, "only the flagship Þór (Thor) could effectively arrest and, if necessary, tow a trawler to harbour".[23][50]

On 4 September, ICGV Ægir, an Icelandic patrol vessel built in 1929,[51] attempted to take a British trawler off the Westfjords, but was thwarted when HMS Russell intervened, and the two vessels collided. On 6 October, V/s María Júlía fired three shots at the trawler Kingston Emerald, forcing the trawler to escape to sea. On 12 November, V/s Þór encountered the trawler Hackness, which had not stowed its nets legally. Hackness did not stop until Þór had fired two blanks and one live shell off its bow. Once again, HMS Russell came to the rescue, and its shipmaster ordered the Icelandic captain to leave the trawler alone, as it was not within the 4 nmi (7.4 km) limit recognised by the British government. The captain of Þór, Eiríkur Kristófersson, said that he would not do so and ordered his men to approach the trawler with the gun manned. In response, the Russell threatened to sink the Icelandic boat if it fired a shot at the Hackness. More British ships then arrived, and the Þór retreated.

Icelandic officials threatened to withdraw Iceland's membership of NATO and to expel US forces from Iceland unless a satisfactory conclusion could be reached to the dispute.[52] Even the cabinet members who were pro-Western (proponents of NATO and the US Defence Agreement) were forced to resort to the threats, as that was Iceland's chief leverage, and it would have been political suicide not to use it.[53] Thus, NATO engaged in formal and informal mediations to bring an end to the dispute.[54]

Following the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea between 1960 and 1961,[38][39][55] the UK and Iceland came to a settlement in late February 1961, which stipulated 12 nmi (22 km) Icelandic fishery limits but that Britain would have fishing rights in allocated zones and under certain seasons in the outer 6 nmi (11 km) for three years.[23] The Icelandic Althing approved the agreement on 11 March 1961.[40]

The deal was very similar to one that Iceland had offered in the weeks and days leading up to its unilateral extension in 1958.[23] As part of the agreement, it was stipulated that any future disagreement between Iceland and Britain in the matter of fishery zones would be sent to the International Court of Justice, in the Hague.

Second Cod War (1972–1973)

| Second Cod War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

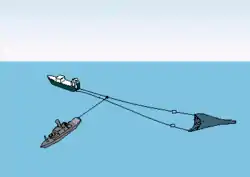

A net cutter, first used in the Second Cod War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| States involved | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1 engineer killed[59] | 1 German trawlerman wounded | ||||||||

The Second Cod War between the United Kingdom and Iceland lasted from September 1972 until the signing of a temporary agreement, in November 1973.

The Icelandic government again extended its fishing limits, now to 50 nmi (93 km). It had two goals in extending the limits: (1) to conserve fish stocks and (2) to increase its share of total catches.[60] The reasons that Iceland pursued 50 nmi fishery limits, rather than the 200 nmi limits that they had also considered, were that the most fruitful fishing grounds were within the 50 nmi and that patrolling a 200 nmi limit would have been more difficult.[61]

The British contested the Icelandic extension with two goals in mind: (1) to achieve the greatest possible catch quota for British fishermen in the contested waters and (2) to prevent a de facto recognition of a unilateral extension of a fishery jurisdiction, which would set a precedent for other extensions.[60][62]

All Western European states and the Warsaw Pact opposed Iceland's unilateral extension.[63] African states declared support for Iceland's extension after a meeting in 1971 where the Icelandic prime minister argued that the Icelandic cause was a part of a broader battle against colonialism and imperialism.[64]

On 1 September 1972, the enforcement of the law that expanded the Icelandic fishery limits to 50 nmi (93 km) began. Numerous British and West German trawlers continued fishing within the new zone on the first day. The Icelandic leftist coalition then governing ignored the treaty that stipulated the involvement of the International Court of Justice. It said that it was not bound by agreements made by the previous centre-right government, with Lúdvik Jósepsson, the fisheries minister, stating that "the basis for our independence is economic independence".[65] The next day, the brand-new patrol ship ICGV Ægir, built in 1968,[66] chased 16 trawlers, in waters east of the country, out of the 50 nmi zone. The Icelandic Coast Guard started to use net cutters to cut the trawling lines of non-Icelandic vessels fishing within the new exclusion zone.

On 5 September 1972, at 10:25,[67] ICGV Ægir, under Guðmundur Kjærnested's command, encountered an unmarked trawler fishing northeast of Hornbanki. The master of the black-hulled trawler refused to divulge the trawler's name and number and, after being warned to follow the Coast Guard's orders, played Rule, Britannia! over the radio.[6] At 10:40, the net cutter was deployed into the water for the first time, and Ægir sailed along the trawler's port side. The fishermen tossed a thick nylon rope into the water as the patrol ship closed in, attempting to disable its propeller. After passing the trawler, Ægir veered to the trawler's starboard side. The net cutter, 160 fathoms (290 m) behind the patrol vessel, sliced one of the trawling wires. As ICGV Ægir came about to circle the unidentified trawler, its angry crew threw coal as well as waste and a large fire axe at the Coast Guard vessel.[67] A considerable amount of swearing and shouting came through the radio, which resulted in the trawler being identified as Peter Scott (H103).[67]

On 25 November 1972, a crewman on the German trawler Erlangen suffered a head injury as an Icelandic patrol ship cut the trawler's trawling wire, which struck the crewman.[68] On 18 January 1973, the nets of 18 trawlers were cut. That forced the British seamen to leave the Icelandic fishery zone unless they had the protection of the Royal Navy. The next day large, fast tugboats were sent to their defence, the first being the Statesman. The British considered that to be insufficient and formed a special group to defend the trawlers.

On 23 January 1973, the volcano Eldfell on Heimaey erupted, forcing the Coast Guard to divert its attention to rescuing the inhabitants of the small island.

On 17 May 1973, the British trawlers left the Icelandic waters, only to return two days later when they were escorted by British frigates.[6] The naval deployment was codenamed Operation Dewey.[69] Hawker Siddeley Nimrod jets flew over the contested waters and notified British frigates and trawlers of the whereabouts of Icelandic patrol ships.[70] Icelandic statesmen were infuriated by the entry of the Royal Navy and considered to appeal to the UN Security Council or call for Article 5 of the NATO Charter to be implemented. According to Frederick Irving, US ambassador to Iceland at the time, Icelandic prime minister Ólafur Jóhannesson demanded that the US send jets to bomb the British frigates.[70] There were major protests in Reykjavík on 24 May 1973. All the windows of the British embassy in Reykjavík were broken.[71]

On 26 May, ICGV Ægir ordered the Grimsby trawler Everton to stop, but the captain of the fishing vessel refused to submit. The incident was followed by a protracted pursuit during which Ægir fired first blank warning shots, later live rounds in order to disable the trawler. Everton was hit on her bow by four 57 mm shells and water began to rush in, but managed to limp to the protection zone, where she was assisted by the frigate HMS Jupiter.[72] Emergency repairs were carried out by a naval team from Jupiter. Prime minister Ólafur Jóhannesson said about the incident that this was "a natural and inevitable law‐enforcement action".[73]

The Icelandic lighthouse tender V/s Árvakur collided with four British vessels on 1 June, and six days later, on 7 June, ICGV Ægir collided with HMS Scylla, when the former was reconnoitring for icebergs off the Westfjords, near the edge of the Greenland ice sheet. The Icelandic Coast Guard reported that Scylla had been "shadowing and harassing" the Icelandic patrol boat. The British Ministry of Defense claimed that the gunboat intentionally rammed the British frigate.[74]

On 29 August[75] the Icelandic Coast Guard suffered the only confirmed fatality of the conflict, when ICGV Ægir collided with HMS Apollo. Halldór Hallfreðsson, an engineer on board the Icelandic vessel, died by electrocution from his welding equipment after sea water flooded the compartment in which he was making hull repairs.[59][76][77]

On 16 September 1973, Joseph Luns, Secretary-General of NATO, arrived in Reykjavík to talk with Icelandic ministers, who had been pressed to leave NATO, as it had been of no help to Iceland in the conflict.[54] Britain and Iceland were both NATO members. The Royal Navy made use of bases in Iceland during the Cold War to fulfill its primary NATO duty, guarding the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap.

After a series of talks within NATO, British warships were recalled on 3 October.[78] Trawlermen played Rule Britannia! over their radios, as they had done when the Royal Navy entered the waters. They also played "The Party's Over".[78] An agreement was signed on 8 November to limit British fishing activities to certain areas inside the 50 nmi limit. The agreement, resolving the dispute, was approved by the Althing on 13 November 1973.[79] The agreement was based on the premise that British trawlers would limit their annual catch to no more than 130,000 tons. The Icelanders were reportedly prepared to settle for 156,000 tons in July 1972 but had increased their demands by spring of 1973 and coffered 117,000 tons (the British demanded 145,000 tons in spring 1973).[80] The agreement expired in November 1975, and the third "Cod War" began.

The Second Cod War threatened Iceland's membership in NATO and the US military presence in Iceland. It was the closest that Iceland has come to canceling its bilateral Defence Agreement with the US.[81]

Icelandic NATO membership and hosting of US military had considerable importance to Cold War strategy because of Iceland's location in the middle of the GIUK gap.

After the entry of the Royal Navy into the contested waters, at any given time, four frigates and an assortment of tugboats would generally protect the British trawling fleet.[82] Over the course of this Cod War, a total of 32 British frigates had entered the contested waters.[83]

C. S. Forester incident

On 19 July 1974,[84] more than nine months after the signing of the agreement, one of the largest wet fish stern trawlers in the British fleet, C. S. Forester,[85] which had been fishing inside the 12 nmi (22 km) limit, was shelled and captured by the Icelandic gunboat V/s Þór ("Thor") after a 100 nmi (185 km) pursuit.[86] C. S. Forester was shelled with non-explosive ammunition after repeated warnings. The trawler was hit by at least two rounds, which damaged the engine room and a water tank.[87] She was later boarded and towed to Iceland.[88] Skipper Richard Taylor was sentenced to 30 days imprisonment and fined £5,000.[lower-alpha 2] He was released on bail after the owners paid £2,232. Her owners additionally paid a total of £26,300 for the release of the ship. The trawler was allowed to depart with a catch of 200 tons of fish.[86][lower-alpha 3]

Third Cod War (1975–1976)

| Third Cod War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cod Wars | |||||||||

Icelandic patrol ship ICGV Óðinn and British frigate HMS Scylla clash in the North Atlantic. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| States involved | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| |||||||||

At the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1973, several countries supported a 100 nmi (185 km) limit to territorial waters.[38][39][92] On 15 July 1975, the Icelandic government announced its intention to extend its fishery limits.[93] The Third Cod War (November 1975 – June 1976) began after Iceland again extended its fishing limits, now to 200 nmi (370 km) from its coast. The British government did not recognise the large increase to the exclusion zone and so an issue occurred with British fishermen and their activity in the disputed zone. The conflict, which was the most hard-fought of the Cod Wars, saw British fishing trawlers have their nets cut by the Icelandic Coast Guard, and there were several incidents of ramming by Icelandic ships and British trawlers, frigates and tugboats.

One of the most serious incidents occurred on 11 December 1975. As reported by Iceland, V/s Þór, under the command of Helgi Hallvarðsson, was leaving port at Seyðisfjörður, where it had been minesweeping, when orders were received to investigate the presence of unidentified foreign vessels at the mouth of the fjord. The vessels were identified as three British ships: Lloydsman, an oceangoing tug three times bigger than V/s Þór; Star Aquarius, an oil rig supply vessel of British Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; and the latter's sister ship, Star Polaris. They were sheltering from a force nine gale within Iceland's 12-nautical-mile (22 km) territorial waters.[94] In the Icelandic account, when ordered to leave Icelandic territorial waters by the commander of Þór, the three tugboats initially complied. However, around 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) from the coast, Star Aquarius allegedly veered to starboard and hit Þór's port side as the Coast Guards attempted to overtake her. Even as Þór increased speed, Lloydsman again collided with its port side. Þór had suffered considerable damage by these hits and so when Star Aquarius came about, a blank round was fired from Þór. That did not deter Star Aquarius, as it hit Þór a second time. Another shot was fired from Þór as a result, this time a live round that hit the bow of Star Aquarius. Then, the tugboats retreated. V/s Þór, which was close to sinking after the confrontation, sailed to Loðmundarfjörður for temporary repairs.[95]

The British reports of the incident differ considerably and maintain that Þór attempted to board one of the tugboats, and as Þór broke away, Lloydsman surged forward to protect Star Aquarius. Captain Albert MacKenzie of Star Aquarius said that Þór approached from the stern and hit the support vessel before it veered off and fired a shot from a range of about 100 yards (90 m). Niels Sigurdsson, the Icelandic Ambassador in London, said that Þór had been firing in self-defence after it had been rammed by British vessels. Iceland consulted the UN Security Council over the incident, which declined to intervene.[96]

The immediate Royal Navy response was to dispatch a large frigate force, which was already well on the way to Icelandic waters, before the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, or the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Crosland, were informed.[97] The Royal Navy saw the opportunity to demonstrate the capabilities of its older Type 12 and Type 81 frigates for sustained deployment in the area of the Denmark Strait, where they were expected to deter the passage of Soviet submarines while the Royal Navy was threatened by further serious defence and naval cuts by the Royal Navy's chief bête noire, the Chancellor of Exchequer and former Minister of Defence, Denis Healey.[98] The Royal Navy saw its strategic aim at the time to be as much fighting Healey as the Soviet Navy.[98] The Second and Third Cod Wars were seen as necessary conflicts by the Royal Navy, like the Falklands War, six years later.[99] To Crosland, also MP for the trawler port of Grimsby, the third war was a more serious threat to the Western Alliance than was the Middle East.[100]

Another incident occurred in January 1976, when HMS Andromeda collided with Þór, which sustained a hole in its hull; the hull of Andromeda was dented. The British Ministry of Defence said that the collision represented a "deliberate attack" on the British warship "without regard for life". The Icelandic Coast Guard, on the other hand, insisted that Andromeda had rammed Þór by "overtaking the boat and then swiftly changing course". After the incident and facing a growing number of ships enduring dockyard repairs, the Royal Navy ordered a "more cautious approach" in dealing with "the enemy cutting the trawlers' warps".[101]

On 19 February 1976, the British Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Fred Preat, announced that a fisherman from Grimsby had become the first British casualty of the Third Cod War, when a hawser hit and seriously injured him after Icelandic vessels cut a trawl.[15] While a British parliamentary source reported in a 1993 debate that a British trawlerman was accidentally killed by a solid shot fired by an Icelandic patrol boat,[102] this suggestion has not been corroborated by any other historical source.

Britain deployed a total of 22 frigates and ordered the reactivation from reserve of the Type 41 frigate HMS Jaguar and Type 61 HMS Lincoln, refitting them as specialist ramming craft with reinforced wooden bows. In addition to the frigates, the British also deployed a total of seven supply ships, nine tugboats and three support ships to protect its fishing trawlers, but only six to nine of the vessels were on deployment at any one time.[103] The Royal Navy was prepared to accept serious damage to its Cold War frigate fleet, costing millions and disabling part of its North Atlantic capacity for more than a year. HMS Yarmouth had its bow torn off, HMS Diomede had a 40 ft gash ripped through her hull, and HMS Eastbourne suffered such structural damage from ramming by Icelandic gunboats that it had to be reduced to a moored operational training frigate. Iceland deployed four patrol vessels (V/s Óðinn, V/s Þór, V/s Týr, and V/s Ægir) and two armed trawlers (V/s Baldur and V/s Ver).[103][104] The Icelandic government tried to acquire US Asheville-class gunboats and when it was denied by Henry Kissinger, it tried to acquire Soviet Mirka-class frigates instead.

A more serious turn of events came when Iceland threatened closure of the NATO base at Keflavík, which would have severely impaired NATO's ability to deny access to the Atlantic Ocean to the Soviet Union. As a result, the British government agreed to have its fishermen stay outside Iceland's 200 nmi (370 km) exclusion zone without a specific agreement.

On the evening of 6 May 1976, after the outcome of the Third Cod War had already been decided, V/s Týr was trying to cut the nets of the trawler Carlisle when Captain Gerald Plumer of HMS Falmouth ordered it rammed. Falmouth, at a speed of more than 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), rammed Týr, almost capsizing her. Týr did not sink and managed to cut the nets of Carlisle, and Falmouth rammed it again. Týr was heavily damaged and found herself propelled by only a single screw and pursued by the tugboat Statesman. In the dire situation, Captain Guðmundur Kjærnested gave orders to man the guns, in spite of the overwhelming superiority of firepower HMS Falmouth enjoyed, to deter any further ramming.[105] In return, Falmouth suffered heavy bow damage.[106][107] The Third Cod War saw 55 ramming incidents altogether.[108]

In NATO-mediated sessions,[54] an agreement was reached between Iceland and the UK on 1 June 1976. The British were allowed to keep 24 trawlers within the 200 nmi limit and fish a total of 30,000 tons.[109]

While Iceland came closest to withdrawing from NATO and expelling US forces in the Second Cod War, Iceland actually took the most serious action in all of the Cod Wars in the Third Cod War by ending diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 19 February 1976.[6] Although the Icelandic government was firmly pro-Western, the government linked Iceland's NATO membership with the outcomes of the fishery dispute. If a favourable outcome could not be reached, Iceland implied that it would withdraw from NATO. However, the government never explicitly linked the US Defence Agreement to the outcome of the dispute.[6]

Results

Iceland achieved its overall aims. As a result, the already-declining British fisheries were hit hard by being excluded from historical prime fishing grounds[110] and the economies of the large northern fishing ports in the United Kingdom, such as Grimsby, Hull, and Fleetwood, were severely affected, with thousands of skilled fishermen and people in related trades being put out of work.[111] The cost for repairing the damaged Royal Navy frigates was probably over £1 million at the time.[lower-alpha 4][112]

In 2012, the British government offered a multimillion-pound compensation deal and apology to fishermen who lost their livelihoods in the 1970s. More than 35 years after the workers lost their jobs, the £1,000 compensation offered to 2,500 fishermen was criticised for being insufficient and excessively delayed.[113]

Scholarship

A 2016 review article finds that the underlying drivers behind the desire to extend fishery limits were economic and legal for Iceland, but they were economic and strategic for the United Kingdom.[10] It, however, argues that "these underlying causes account for the tensions but are not enough to explain why bargaining failure occurred".[10] After all, the outbreak of each Cod War was costly and risky for both sides.

Several factors are mentioned to explain why bargaining failure occurred.[10] The nature of nationalism and party competition for Iceland and pressure from the trawling industry for Britain are reasons that both sides took actions that were of noticeable risk to their broader security interests. Interdepartmental competition and unilateral behaviour by individual diplomats were also factors, with the British Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries influencing the British government's decision "more than the Foreign Office".[10]

A 2017 study argues that both a combination of powerful domestic pressures on statesmen to escalate and miscalculation by those statesmen contributed to the outbreak of the Cod Wars.[16] The study argues that Iceland won each of the Cod Wars because Icelandic statesmen were too greatly constrained by domestic politics to offer compromises to the British, but British statesmen were not as constrained by public opinion at home.[16]

Lessons drawn for international relations

International relations scholars such as Robert Keohane, Joseph Nye, Hans Morgenthau, Henry Kissinger and Ned Lebow have written on the Cod Wars.[10]

The 2016 review article finds that lessons from the Cod Wars have most commonly been applied to liberal and realist schools of international relations theory and theories on asymmetric bargaining.[10] It claims that the Cod Wars are widely seen as inconsistent with the precepts of the liberal peace, since democracy, trade and institutions are supposed to pacify interstate behaviour.[10] A 2017 study argues that the "supposedly pacifying factors of the liberal peace – democracy, trade and institutional ties – effectively made the disputes more contentious".[17] The Cod Wars are also held up as an example of the decreasing salience of hard power in international relations, with implications for realist theory which emphasizes the importance of hard power.[10] Theorists on asymmetric bargaining have emphasized how Iceland, lacking structural power, can still have an issue power advantage, with its greater commitment to the cause.[10]

Legacy

The 1976 agreement at the end of the Third Cod War forced the UK to abandon the "open seas" international fisheries policy it had previously promoted.[21][114] The British Parliament passed the Fishery Limits Act 1976, declaring a similar 200-nautical-mile zone around its own shores,[115][lower-alpha 5] a practice later codified into the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which provided similar rights to every sovereign nation.[21][39]

The victories in the Cod Wars may have strengthened Icelandic nationalism and boosted the perception that Iceland can succeed through unilateral or bilateral means rather than compromise in multilateral frameworks, such as membership of the European Union.[116][lower-alpha 6]

The Cod Wars are often mentioned in Icelandic and British news reporting when either state is involved in a fishery dispute or when there are disputes of some sort between the two countries. The Cod Wars were extensively covered by media during the Icesave dispute between Iceland and the UK,[121][122][123] and in preparation for the Iceland–England match at the round of 16 in Euro 2016.[124][125][126]

In February 2017, the crews of two ships involved in the Cod Wars, the Hull trawler Arctic Corsair and the Icelandic patrol ship ICGV Óðinn, exchanged bells in a gesture of goodwill and sign of friendship between the cities of Hull and Reykjavík. The event was part of a project by Hull Museums on the history between Iceland and the United Kingdom during and after the Cod Wars.[127]

See also

Notes

- Iceland has never participated in a full-scale war.[9]

- About £53,000 as of 2020.[89]

- About £280,000 as of 2020.[89]

- About £11 million as of 2020.[89]

- In practice, the UK's EEZ can only reach its full 200-mile limit off the west coast of Scotland; everywhere else, it is shorter due to the proximity of neighbouring states, such as France, with which the UK has agreed on a boundary.[115] Having joined the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other member states in return.[21] In 1983, the EEC adopted the Common Fisheries Policy. The issue of fishing rights played a role in Brexit in 2016 and the subsequent trade negotiation between the UK and the EU (see Fish for finance).[21]

- The European Union's Common Fisheries Policy is also cited by academics as one of the reasons discouraging Iceland from joining the European Union.[117][116][118] The 2010 Mackerel War played a role in Iceland's withdrawal of its EU membership application the following year.[119][120]

References

- Habeeb, William (1988). "6". Power and Tactics in International Negotiations: How Weak Nations Bargain with Strong Nations. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Cook, Bernard A. (27 January 2014). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 605. ISBN 978-1-135-17932-8. Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Þorsteinsson, Björn (1976). Tíu þorskastríð 1415–1976.

- How Iceland Beat the British in the Four Cod Wars Archived 19 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Gastro Obscura, 21June 2018

- "Cabinet Papers: The Cod Wars". National Archives (UK). Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Guðmundsson, Guðmundur J. (2006). "The Cod and the Cold War". Scandinavian Journal of History. 31 (2): 97–118. doi:10.1080/03468750600604184. S2CID 143956818.

- Ledger, John (21 December 2015). "How the Cod War of 40 years ago left a Yorkshire community devastated". The Yorkshire Post. Archived from the original on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British Trawlers and Iceland 1919–1976. University of Gothenburg. p. 182.

- "From Iceland – Ask A Historian: Has Iceland Ever Been Involved in Any Wars Or Conflicts". The Reykjavik Grapevine. 14 July 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- Steinsson, Sverrir (22 March 2016). "The Cod Wars: a re-analysis". European Security. 25 (2): 256–275. doi:10.1080/09662839.2016.1160376. ISSN 0966-2839. S2CID 155242560.

- Hellmann, Gunther; Herborth, Benjamin (1 July 2008). "Fishing in the mild West: democratic peace and militarised interstate disputes in the transatlantic community". Review of International Studies. 34 (3): 481–506. doi:10.1017/S0260210508008139. ISSN 1469-9044. S2CID 144997884.

- Ireland, Michael J.; Gartner, Scott Sigmund (1 October 2001). "Time to Fight: Government Type and Conflict Initiation in Parliamentary Systems". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 45 (5): 547–568. doi:10.1177/0022002701045005001. JSTOR 3176313. S2CID 154973439.

- Prins, Brandon C.; Sprecher, Christopher (1 May 1999). "Institutional Constraints, Political Opposition, And Interstate Dispute Escalation: Evidence from Parliamentary Systems, 1946–89". Journal of Peace Research. 36 (3): 271–287. doi:10.1177/0022343399036003002. ISSN 0022-3433. S2CID 110394899.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 100.

- "Hansard debates – 19 February 1976". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 19 February 1976. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Steinsson, Sverrir (2017). "Neoclassical Realism in the North Atlantic: Explaining Behaviors and Outcomes in the Cod Wars". Foreign Policy Analysis. 13 (3): 599–617. doi:10.1093/fpa/orw062. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Steinsson, Sverrir (6 June 2017). "Do liberal ties pacify? A study of the Cod Wars". Cooperation and Conflict. 53 (3): 339–355. doi:10.1177/0010836717712293. ISSN 0010-8367. S2CID 157673952.

- Forse, Andy; Drakeford, Ben; Potts, Jonathan (25 March 2019). "Fish fights: Britain has a long history of trading away access to coastal waters". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Chaffin, Joshua (18 July 2017). "North Sea cod completes long journey back to sustainability". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Gardiner, Mark (2016). "8: The character of commercial fishing in Icelandic waters in the fifteenth century". In Barrett, James Harold; Orton, David C. (eds.). Cod and Herring: The Archaeology and History of Medieval Sea Fishing (PDF). Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 80–90. ISBN 9781785702396. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Forse, Andy; Drakeford, Ben; Potts, Jonathan (26 March 2019). "Fish fights: Britain has a long history of trading away access to coastal waters". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British trawlers and Iceland: 1919–1976. p. 9.

- Jóhannesson, Gudni Thorlacius (1 November 2004). "How 'cod war' came: the origins of the Anglo-Icelandic fisheries dispute, 1958–61*". Historical Research. 77 (198): 543–574. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2004.00222.x. ISSN 1468-2281.

- Bale, B. (2010), Memories of the: Lincolnshire Fishing Industry Berkshire: Countryside Books pg. 35

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British trawlers and Iceland: 1919–1976. pp. 48–50.

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British trawlers and Iceland: 1919–1976. pp. 68, 79.

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British trawlers and Iceland: 1919–1976. p. 87.

- Thór, Jón Th. (1995). British trawlers and Iceland: 1919–1976. pp. 91–107.

- Jóhannnesson, Guðni Th. (2007). Troubled Waters. NAFHA.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2007). Troubled Waters. p. 104.

- Thorsteinsson, Pétur (1992). Utanríkisþjónusta Íslands og utanríkismál: Sögulegt Yfirlit 1. p. 440.

- Jóhannesson, Gudni Thorlacius (2004). "Any Port in a Storm. The Failure of Economic Coercion, 1953–54". Troubled Waters. Cod War, Fishing Disputes, and Britain's Fight for the Freedom of the High Seas, 1948–1964 (PhD). Queen Mary, University of London. pp. 91–92. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (1996). Í eldlínu kalda stríðsins. p. 288.

- Þorsteinsson, Björn (1983). "Þorskastríð og fjöldi þeirra". Saga.

- Jónsson, Björn (1981). "Tíunda þorskastríðið 1975–1976". Saga.

- Steinsson, Sverrir (June 2015). Why Did the Cod Wars Occur and Why Did Iceland Win Them? A Test of Four Theories (Master's) (published 4 May 2015). hdl:1946/20916. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- "United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1958". United Nations. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

-

- "The Cod Wars". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2015

- "Icy fishing: UK and Iceland fish stock disputes" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 19 December 2012. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- "The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (A historical perspective)". United Nations. 1998. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. Hafréttarstofnun Íslands. pp. 61–62.

- Associated people and organisations for "HMS Eastbourne on fishery protection duties" Archived 6 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine (August 1958). Imperial War Museum. Accessed 20 January 2014.

- Jóhannesson, Gudni Thorlacius (2004). Troubled Waters: Cod War, Fishing Disputes, and Britain's Fight for the Freedom of the High Seas, 1948–1964 (PDF) (PhD thesis). Queen Mary, University of London. p. 161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

... Barry Anderson, Captain of the Fishery Protection Squadron ...

- Tyrone Daily Herald Archived 7 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, 2 September 1958, p. 1 (OCR text; accessed 20 January 2014).

- Magnússon, Gunnar (1959). Landhelgisbókin. Bókaútgáfan Setberg SF. p. 157.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (1996). Í eldlínu kalda stríðsins. p. 377.

- Sveinn Sæmundsson, Guðmundur skipherra Kjærnested, Örn og Örlygur. Reykjavík. 1984. p. 151.

- Jón Björnsson, Íslensk skip. vol. III. Reykjavik. 1990 p. 8-142 ISBN 9979-1-0375-2

- Svipmyndir úr 70 ára sögu. Landhelgisgæsla Íslands. Reykjavík. 1996. pp. 30–31, 37–38. ISBN 9979-60-277-5

- Jóhannesson, Gudni Thorlacius (1 November 2004). "How 'cod war' came: the origins of the Anglo-Icelandic fisheries dispute, 1958–61". Historical Research. 77 (198): 567–568. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.2004.00222.x. ISSN 1468-2281.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2003). "Did He Matter? The Colourful Andrew Gilchrist and the First Cod War". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Háskólabókasafn, Landsbókasafn Íslands-. "Tímarit.is". timarit.is (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (1996). Í eldlínu kalda stríðsins. pp. 33–34.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (2002). Uppgjör við umheiminn. pp. 33, 36.

- Bakaki, Zorzeta (1 January 2016). "Deconstructing Mediation: A Case Study of the Cod Wars". Negotiation Journal. 32 (1): 63–78. doi:10.1111/nejo.12147. ISSN 1571-9979.

- "Second United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1960". United Nations. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- An agreement was not reached with West Germany until 26 November 1975.Hart, Jeffrey A. The Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1972–1973. 1976. P. 48.

- Hart, p. 28

- "Landhelgisgæslan á flugi" (in Icelandic). Icelandic Coast Guard. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- Guðmundsson, Guðmundur Hörður. 15. Annað þorskastríðið. Tímabilið 19. maí 1973 til nóvember 1973 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hart, Jeffrey A. (1976). The Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1972–1973. Berkeley: University of California. pp. 19, 24.

- Guðmundsson, Guðmundur J. (2000). "Þorskar í köldu stríði". Ný Saga: 67–68. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "Icelandic Fisheries". Commons and Lords Hansard, the Official Report of debates in Parliament. UK Parliament. 22 March 1973. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Inimundarson, Valur (2002). Uppgjör við umheiminn. pp. 146, 162–163.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (2002). Uppgjör við umheiminn. p. 147.

- "History of the Cod Wars Part 3". BBC Four. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2013 – via YouTube. Archived at Ghostarchive.

- Couhat, Jean Labayle (1988). Combat Fleets of the World 1988/89: Their Ships, Aircraft, and Armament. Naval Institute Press. p. 265. ISBN 0870211943. Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Sæmundsson, Sveinn (1984). Guðmundur skipherra Kjærnested. Örn og Örlygur

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 82.

- Flintham, Vic (2008). High Stakes: Britain's Air Arms in Action 1945–1990. Pen and Sword. p. 347. ISBN 978-1844158157.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 90.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 91.

- "Icelandic Ship Shells British Trawler After Chase". The New York Times. 27 May 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- "A Shelled Trawler Repaired by British". The New York Times. 28 May 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- "Iceland Patrol Boat And British Frigate Are in a Collision". The New York Times. 8 June 1973. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- "1973". The Napier Chronicles. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- Hart, Jeffrey A. (1976). The Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1972–1973. p. 44.

- "Dauðsfall um borð i Ægi: Var það alda frá Statesman, sem grandaði manninum?" [Death on board the Ægi: Was it the wake of the Statesman that killed the man?]. Tíminn (in Icelandic). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016 – via National and University Library of Iceland.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 101.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 102.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. pp. 88, 94, 101.

- Ingimundarson, Valur (1 December 2003). "A western cold war: the crisis in Iceland's relations with Britain, the United States, and NATO, 1971–74". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 14 (4): 94–136. doi:10.1080/09592290312331295694. ISSN 0959-2296. S2CID 154735668.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 89.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 103.

- Jessup, John E. (1998).An encyclopedic dictionary of conflict and conflict resolution, 1945–1996. Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 130. ISBN 0-313-28112-2

- Fishing News international, vol. 14, no. 7–12. A. J. Heighway Publications, 1975

- "C S Forester H86". Hulltrawler.net. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- "Commons debate, 29 July 1974". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 29 July 1974. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- The Illustrated London News, vol. 262, no. 2. The Illustrated London News & Sketch Ltd., 1974

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Kassebaum, David (10 April 1997). "Cod Dispute Between Iceland and the United Kingdom". Inventory of Conflict and Environment. American University. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Jones, Robert (2009) Safeguarding the Nation: The Story of the Modern Royal Navy. Seaforth Publishing, p. 119. ISBN 1848320434

- "Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1973–1982". United Nations. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 112.

- Storey, Norman, What price cod? A tugmaster's view of the cod wars. Beverley, North Humberside: Hutton Press. c. 1992. ISBN 1-872167-44-6

- Atli Magnússon, Í kröppum sjó : Helgi Hallvarðsson skipherra segir frá sægörpum og svaðilförum. Örn og Örlygur. [Reykjavík]. 1992. p. 204–206 ISBN 9979-55-035-X.

- Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson, Þorskastríðin þrjú: saga landhelgismálsins 1948–1976, Hafréttarstofnun Íslands. Reykjavík. 2006. ISBN 9979-70-141-2.

- S. Crosland. Tony Crosland. Cape. London (1982)

- Admiral Sandy Woodward (1992). One Hundred Days: Memoirs of a Falklands Battlegroup Commander. Naval Institute Press. RI

- Chris Parry (2013). Down South: A Falklands War Diary. London: Penguin.

- K. Threakston. British Foreign Secretaries since 1974.

- Ships Monthly, Vol. 39, p. 35. Endlebury, 2004

- "Tuesday 30 March 1993". hansardarchiv.es. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Jane's fighting ships: the standard reference of the world's navies. London.

- Atli Magnússon, Í kröppum sjó : Helgi Hallvarðsson skipherra segir frá sægörpum og svaðilförum. Reykjavik: Örn og Örlygur. 1992. pp. 201–202

- Óttar Sveinsson, Útkall: Týr er að sökkva. Reykjavik: Útkall. 2004. ISBN 9979-9569-6-8.

- Roberts, John (2010). Safeguarding the Nation: The Story of the Modern Royal Navy. Seaforth Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-1848320437.

- "Conflict at sea during furious 1970's Cod Wars". The News. Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Cod Wars". britishseafishing.co.uk. 19 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Jóhannesson, Guðni Th. (2006). Þorskastríðin þrjú. p. 145.

- Georg H. Engelhard (2008). "One hundred and twenty years of change in fishing power of English North Sea trawlers". In Andy Payne, John Cotter, and Ted Potter (eds.). Advances in fisheries science: 50 years on from Beverton and Holt, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 1-4051-7083-2, p. 1 doi:10.1002/9781444302653.ch1, mirror Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Teed, Peter (1992). The Dictionary of Twentieth Century History, 1914–1990. Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-19-211676-2

- Robinson, Robb (1996). Trawling: the rise and fall of the British trawl fishery. University of Exeter Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0859894807.

- Nick Drainey (6 April 2012). "Cod Wars payment is 'too little, too late'". The Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Privatising the seas: how the UK turned fishing rights into a commodity". Unearthed. 7 March 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Churchill, Robin (November 2016). "Possible EU Fishery Rights in UK Waters And Possible UK Fishery Rights in EU Waters Post-Brexit: An Opinion Prepared for the Scottish Fishermen's Federation" (PDF). Scottish Fishermen's Federation. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Thorhallsson, Baldur (2004). Iceland and European Integration: On the Edge. Routledge.

- Ingebritsen, Christine (1998). The Nordic States and European Unity. Cornell University Press.

- Bergmann, Eirikur (1 January 2017). "Iceland: Ever-Lasting Independence Struggle". Nordic Nationalism and Right-Wing Populist Politics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 93–124. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-56703-1_4. ISBN 9781137567024.

- Kaufman, Alexander C. (18 August 2019). "Brexit Could Spark The Next Big Fishing War". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Davies, Caroline (22 August 2010). "Britain prepares for mackerel war with Iceland and Faroe Islands". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Loftsdóttir, Kristín (14 March 2016). "Building on Iceland's 'Good Reputation': Icesave, Crisis and Affective National Identities". Ethnos. 81 (2): 338–363. doi:10.1080/00141844.2014.931327. ISSN 0014-1844. S2CID 144668345.

- Bergmann, E. (30 January 2014). Iceland and the International Financial Crisis: Boom, Bust and Recovery. Springer. ISBN 9781137332004. Archived from the original on 23 July 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "Iceland holds referendum on Icesave repayment plan". BBC News. 6 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "When tiny Iceland did beat England: It's time to brush up on the Cod Wars". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Celebrate Icelandic victory in the Cod Wars at a Coast Guard open house on Sunday". Icelandmag. Archived from the original on 18 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Iceland invoke the spirit of the Cod Wars in bid to beat England". The Independent. 26 June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- "Cod Wars fishing vessels to exchange bells in cooperation gesture". BBC News. 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

Further reading

- Frost, Natasha (21 June 2018). "How Iceland Beat the British in the Four Cod Wars". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Ingo Heidbrink: "Deutschlands einzige Kolonie ist das Meer" Die deutsche Hochseefischerei und die Fischereikonflikte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg (Convent Vlg) 2004.

- Kurlansky, Mark. Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. New York: Walker & Company, 1997 (reprint edition: Penguin, 1998). ISBN 0-8027-1326-2, ISBN 0-14-027501-0.

- Glantz, Michael H. (2005). Climate variability, climate change, and fisheries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 264–283. ISBN 9780521017824.

- Jónsson, Hannes (1982). Friends in conflict: the Anglo-Icelandic cod wars and the Law of the Sea. C. Hurst. ISBN 0-208-02000-4

- Why Did the Cod Wars Occur and Why Did Iceland Win Them? A Test of Four Theories (PDF). Faculty of Political Science – School of Social Sciences – University of Iceland. 2015. p. 31.

External links

- Case Study – The Cod War

- MV Miranda Site Website of the MV Miranda, a Trawler support vessel

- Britain's Small Wars – The Cod War

- BBC Archived 20 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine Video footage from the BBC

- Fiskveiðideilur Íslendinga við erlendar þjóðir, by Guðni Jóhannesson (in Icelandic)

- BBC 'On this Day' 1973: Royal Navy moves to protect trawlers

- BBC 'On this Day' 1975: "Attack on British vessels heightens Cod War"

- Henry Kissinger talking about cod war between Iceland and the United Kingdom, AP Archive, 2 February 1973