3rd Tipperary Brigade

The 3rd Tipperary Brigade (Irish: Tríú Briogáid Thiobraid Árainn[1]) was one of the most active of approximately 80 such units that constituted the IRA during the Irish War of Independence. The brigade was based in southern Tipperary and conducted its activities mainly in mid-Munster.

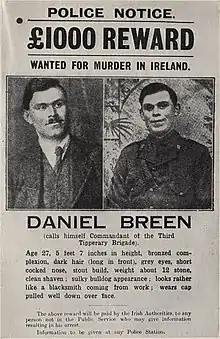

In December 1918 and January 1919, in a tin hut on a dairy farm in Greenane, Tipperary, members of the brigade planned what was to be the first act of the Irish War of Independence, the Soloheadbeg Ambush. In the early part of the war, four members of the brigade were the most wanted men in Ireland. The 'Big Four', as they were referred to in Ireland in 1919, were Seán Treacy, Dan Breen, Séumas Robinson and Seán Hogan. Raids, ambushes and ongoing military activities by the brigade battalions and flying columns made South Tipperary ungovernable for the British in 1920 and 1921, with the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) confined to what barracks remained occupied and the British Army only venturing out in large convoys.

Background

The period between the Easter Rising of 1916 and the start of the Irish War of Independence in January 1919, was one of growing tensions between the nationalist element of the Irish population and those in authority, particularly the RIC and British authorities. These tensions were set against the backdrop of increased membership of nationalist volunteer organizations across the country and meetings and open drilling of volunteer companies coupled with the jailing of a large number of political prisoners, raids on houses of political activists by the RIC and incidents such as the death of hunger striker Thomas Ashe.[2] 1918 saw the political stakes raised with the Military Service Bill coming into effect making conscription in Ireland legal and the proclamation issued banning nationalist organizations such as Sinn Féin, the Irish Volunteers, the Gaelic League and Cumann na mBan.The response to these measures was a significant upswing in anti British sentiment, emphasized by the overwhelming victory by Sinn Féin in the 1918 General Election and the anti-conscription rallies.[3] While some in the nationalist movement were satisfied with political victories there was an element that argued that the only way Ireland would ever obtain freedom was through a military confrontation with the British and particularly those who served British interests in Ireland.

By 1917 in South Tipperary, the volunteers were being formed into companies with regular drilling and instructions on the use of firearms. Raids for arms were undertaken during 1917 and 1918 as the Volunteer companies were arming themselves in the anticipation of future conflict.[4] Seán Treacy was the driving force behind a lot of this activity and he regularly visited the local companies often accompanied by Dan Breen. The visit of de Valera to Tipperary Town in August 1917 generated great interest and enthusiasm. Treacy was Éamon de Valera's body guard when he came to Tipperary in 1917 to speak at political rallies. Treacy was arrested a short time later and sentenced to 6 months jail.[5] The jails were full of activists who were arrested for drilling, singing banned nationalistic songs, parading in uniform etc. and they became a school for revolutionaries with men from all over Ireland discussing the plight of their country and what needed to be done to progress their cause. In the 1918 General Election, Sinn Féin candidates were overwhelmingly returned in County Tipperary. The relationship between the RIC and the Volunteers was increasingly hostile with clashes at political rallies or while the Volunteers were drilling. Séumas Robinson, a veteran of the 1916 Easter Rising, arrived in Tipperary in 1917 at the request of Eamon Uí Dubhir who he had met while they were both imprisoned.[6] Eamon Uí Dubhir and Maurice Crowe along with Treacy, Breen and Robinson were prominent in leading the activity of the Volunteers in South Tipperary in 1917 and 1918.

Establishment

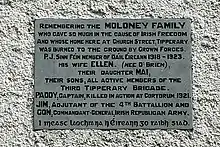

The Third Tipperary Brigade, also known as the South Tipperary Brigade, was established in 1918. In October 1918 a Brigade meeting was held to elect officers, at P.J. Moloney's house in Church Street, Tipperary Town. Moloney was later in the year elected as a Sinn Féin MP. The house was burnt down during the war by British forces. Moloney's three sons were all members of the brigade. Richard Mulcahy from GHQ presided over the meeting.[7] Séumas Robinson was elected O/C (in absentia as he was imprisoned at the time and did not rejoin the Brigade until late December), Seán Treacy vice O/C, Dan Breen Quarter Master and Maurice Crowe Adjuntant. The Brigade originally had 6 Battalions with this later being extended to 8. These were Rosegreen, Cashel, Dundrum, Tipperary, Clonmel, Cahir, Drangan and Carrick-on-Suir.[8]

After Seán Treacy was released from Dundalk prison in mid 1918, Treacy and Breen along with Seán Hogan set up their headquarters in the 'Tin Hut' in Greenane. Here they tested explosives and planned activities. The 'Tin Hut' was a frequent haunt for many who would later play an important part in the Brigade's activities in the war, including Maurice Crowe, Dinny Lacey, Tadhg Crowe and Patrick O'Dwyer.[9]

Soloheadbeg

The ambush led by Seamus Robinson, Sean Treacy, Daniel Breen and Seán Hogan at Soloheadbeg is generally acknowledged as the opening engagement of the war. Two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary were killed in the attack - Constable Patrick O'Connell and Constable James McDonnell.

The planning for Soloheadbeg took place in the 'Tin Hut' on a dairy farm in Greenane. Treacy, Breen and Hogan had been undertaking experiments with explosives there and considering ways to attack the RIC. Treacy was keen to commence hostilities and believed a military confrontation with the RIC and the British authorities was the only way to establish the Republic that Ireland had proclaimed in 1916 and voted for in 1918. In December 1918, they received information that there were plans to move a consignment of gelignite from the Tipperary Town military barracks to the Soloheadbeg quarry.

Treacy consulted his commanding officer, Seamus Robinson, who gave the go-ahead without consulting General Headquarters in Dublin, on the basis that what the eye does not see the heart will not grieve over.[10]

They commenced plans to intercept the consignment and Dan Breen's brother Lars, who worked at the quarry, received information that the consignment was to be moved around 16 January 1919. They anticipated that there would be between 2-6 armed escorts and they discussed different contingencies, such as where they would guard the RIC if they surrendered and that they would fire on the escort if they did not immediately surrender.[11] Robinson, who had returned to the Brigade area after his release from jail, was briefed by Treacy about the plans to seize the gelignite. Robinson supported the plan and confirmed with Treacy that they would not request permission from GHQ, if they did they would be obliged to wait for a response and even if the response was affirmative it might come back after the gelignite was moved.[12]

'Those involved on the day of the operation were four officers of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade IRA; Seán Treacy, Dan Breen, Seán Hogan (then only 17) and Séumas Robinson. They were joined by five other Volunteers: Tadhg Crowe, Patrick McCormack, Paddy O'Dwyer, Michael Ryan (Donohill) and Seán O'Meara (Tipperary) - the latter two being cycle scouts.[13]

On each day from January 16 to January 21, the men selected for the ambush took up their positions from early in the morning to late afternoon and then retired and spent the night at the 'Tin Hut'. On 21 January around noon, Patrick O'Dwyer noticed the convoy leaving the barracks. The consignment was on a horse-drawn cart, led by two council men with two armed RIC constables guarding the consignment. O'Dwyer cycled quickly to where the ambush party was waiting and informed them of the details of the convoy.[14]

Robinson and O'Dwyer hid about 30 metres in front of the main ambush party of six, in case they rushed through the main ambush position. After the convoy reached the position where the main ambush party was hiding, they called on the RIC officers to surrender as masked men appeared in front of them with their guns drawn. The two constables took up firing positions and the volunteers fired upon them. Both RIC constables, Patrick O'Connell and James McDonnell, were killed.[15] As planned, Hogan, Breen and Treacy took the horse and cart with the explosives and sped off. They hid the explosives in a field in Greenane and threw a few sticks out on the roadside a few miles further on as a decoy. The explosives were moved several times and later divided up between the battalions of the brigade.[16] Tadhg Crowe and Patrick O'Dwyer took the guns and ammunition from the dead constables, while Robinson, McCormack and Ryan guarded the two council workers before releasing them once the gelignite was far enough away.[17]

Breen has left apparently conflicting accounts of their intentions that day. One implies that the purpose of the confrontation was merely to capture explosives and detonators being escorted to a nearby quarry.[18] The other, that the group intended killing the police escort to provoke a military response.

"Treacy had stated to me that the only way of starting a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a war, so we intended to kill some of the police whom we looked upon as the foremost and most important branch of the enemy forces ... The only regret that we had following the ambush was that there were only two policemen in it, instead of the six we had expected."[19]

However, Robinson said that the plan was to call on the RIC men to surrender if there were only two, but to attack if there were six, as the eight IRA men armed only with one rifle (Treacy) and revolvers would be outgunned by eight.

"The reason for the difference was that there would be so little danger to us if only two appeared that it would be inhuman not to give them an opportunity of surrendering, but if six police turned up they, with their rifles, would be too great a danger to the eight of us to take any such risk as to challenge them and thus hand over our initiative. We had only one Winchester Repeater rifle and an agglomeration of small-arms.

On the run

As a result of the Soloheadbeg ambush, martial law was declared in County Tipperary.

Treacy, Breen and Hogan met again with Robinson a few weeks later and the "big four" as they were locally called, remained in hiding over the coming months, moving from house to house of sympathisers or sleeping in the rough in the countryside. Treacy and Robinson traveled to Dublin to consult Michael Collins who offered to arrange for them and Breen and Hogan to escape to America. They rejected the offer and told Collins they would remain in Ireland and continue the fight.

Hogan, who was only eighteen years old, was arrested by the RIC in May 1919. His capture would lead to one of the dramatic events of the war. Robinson, Treacy and Breen, supported by men from the East Limerick Brigade rescued a handcuffed Hogan from a train under the guard of four RIC officers at Knocklong station in Limerick. Hogan would almost certainly have been executed if he was not rescued. Two of the RIC were killed in the fight and Breen and Treacy seriously injured. The four men regrouped at the home of the Foley family, who lived nearby. Two years later Edmond Foley, a son of that house, was executed on suspicion of being involved in Hogan's rescue. [21]

Robinson, Treacy, Hogan and Breen relocated to Dublin and undertook a range of missions under the direction of the Dublin leadership, some of these missions were in association with a unit known as The Squad. Robinson initially and Hogan later returned to Tipperary to continue the fight against the British and the RIC in Tipperary and surrounding counties. Treacy was eventually killed in an exchange of fire with a British secret service agent in Talbot Street, while Breen alternated between Tipperary and Dublin as the conflict continued.

Raids on RIC barracks

Aside from the RIC hunt for 'the big four' the remainder of 1919 was reasonably quiet in South Tipperary. This changed in early to mid 1920 as the battalions of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade mounted a series of raids on RIC barracks, including attacks on the barracks at Hollyford, Drangan, Cappawhite, Rear Cross and Clerihan.[22]

Robinson continued to command the brigade through the rest of the war of independence. In September 1920 he appointed Dinny Lacey as O/C of the brigade's first flying column and later that year a second flying column was established with Seán Hogan as O/C.[23]

Civil War

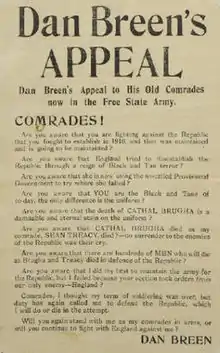

Reservations about the Treaty caused division within the Brigade. Some members sided with the Provisional Government, (later the Irish Free State), while others remained neutral during the ensuing Civil War. The majority, including Brigade Officers Séumas Robinson, Dan Breen, Seán Hogan and Dinny Lacey, took the Republican side. Lacey was killed in action against Free State troops in 1923 in the Glen of Aherlow while Robinson was a General throughout the civil war, Breen and Hogan were both interned by the Free State Army during the Civil War.

Third Tipperary Brigade Commemorations

A memorial at St Michael's Cemetery, Tipperary Town lists the names of those brigade members who were killed in the War of Independence and the Civil War. There are numerous memorials, plaques and statues in Tipperary and surrounding areas that commemorate members of the brigade or actions of the brigade, including those at Soloheadbeg, Knocklong, Talbot Street, Dublin, Annacarthy, Drangan and Ballingarry. The Sean Treacy Memorial swimming pool in Tipperary Town displays information about and a number of artefacts of the brigade.

A number of songs recall events and members of the brigade including:

- The Galtee Mountain Boy – three of the four named historical figures in the song "The Galtee Mountain Boy" were members of the Third Tipperary Brigade, Flying Column leaders Dinny Lacey & Seán Hogan and the Brigade's Quartermaster, Dan Breen.

- "Tipperary So Far Away" (Ballad of Sean Treacy). This song recounts the death of Sean Treacy. A line from the song was quoted by Ronald Reagan when he visited Ballyporeen in 1984: "And I'll never more roam, from my own native home, in Tipperary so far away.".[24]

- Ballad of Dan Breen[25]

- Station of Knocklong, about Sean Hogan's rescue.[26]

Online sources

Tipperary Historical Society : The Third Tipperary Brigade a Photographic Record - Neil Sharkey 1994

Bureau of Irish Military History - Séumas Robinson's witness statement https://web.archive.org/web/20171123144125/http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1721.pdf#page=113

List of Brigade members who were killed in the conflict

Tipperary Brigade

Ó Duibhir : The Tipperary Volunteers in 1916: A Personal Account 75 Years On

Aengus O Snodaigh (21 January 1999). "Gearing up for war: Soloheadbeg 1919". An Phoblacht.

Brendan A. Creaner : The Rescue at Knocklong (8 December 2003)

Colmcille : (a) : The Third Tipperary Brigade (1921–1923); Part I- From Truce to Civil War : THJ : 1990

Colmcille : (b) : The Third Tipperary Brigade (1921–1923); Part II- From Ambushes to Executions : THJ : 1991

Colmcille : (c) : The Third Tipperary Brigade (1921–1923); Part III- The End of the Civil War: THJ : 1992

All preceding accessed on or after 2 Nov 2008

Bibliography

- Breen, Dan (1926). My Fight for Irish Freedom. Talbot Press.

- Ryan, Desmond (1945). Sean Treacy and the Third Tipperary Brigade I.R.A. Kerryman Limited.

- Augusteijn, Joost (1996). From public defiance to guerrilla warfare the experience of ordinary volunteers in the Irish war of independence, 1916-1921. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-2607-0.

- Shelley, John R. A Short History of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade Published by (Phoenix) : 1996

- Irish Republican Army. South Tipperary Brigade (1923). Poblacht Na H-Eireann Proclamation [explaining the Reasons why the Brigade Feel Impelled to Take Up Arms Against the Government].

- Peter Berresford Ellis (2007). Eyewitness to Irish History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-05312-6.

- All preceding accessed 2 Nov 2008

References

- "Coimisiún na Scrúduithe Stáit". Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- The IRB: The Irish Republican Brotherhood from The Land League to Sinn Féin, Owen McGee, Four Courts Press, 2005,

- Wikipedia page - 1918 in Ireland

- Aengus O Snodaigh (21 January 1999). "Gearing up for war: Soloheadbeg 1919". An Phoblacht.

- Ryan, Desmond (1945). Seán Treacy and the Third Tipperary Brigade I.R.A. Kerryman Limited.

- Bureau of Military History - Witness Statement 1348 Michael Davern

- Irish Burea of Military History- witness statement 1658, Tadhg Crowe

- Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1433, Michael Fitzpatrick

- Irish Bureau of Military History - Witness Statement 1432, Patrick O'Dwyer

- Bureau of Military History witness statement of Seamus Robinson https://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1721.pdf#page=113

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1432 Patrick O'Dwyer

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1721, Séumas Robinson

- Aengus O Snodaigh (21 January 1999)'. "Gearing up for war: Soloheadbeg 1919

- Aengus O Snodaigh (21 January 1999)'. "Gearing up for war: Soloheadbeg 1919

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1432 Patrick O'Dwyer

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1450, John Ryan

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1432 Patrick O'Dwyer

- Peter Berresford Ellis (2007). Eyewitness to Irish History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-470-05312-6.

- History Ireland, May 2007, p.56.

- Irish Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement 1721, Séumas Robinson

- Seamus Robinson witness statement, Bureau of Military History

- A short History of the Third Tipperary Brigade - John R Shelley - Phoenix Publishing 1996

- Irish Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 1433, Michael Fitzpatrick

- Speech at Ballyporeen Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Tipperay by US President Ronald Reagan, June 3, 1984

- "The Ballad of Dan Breen". YouTube.

- "The Station of Knocklong - Clover Limerick Ireland (Official Video)". YouTube.