Thomas Birch (English Parliamentarian)

Thomas Birch, c. 5 June 1608 to 5 August 1678, was an English landowner, soldier and radical Puritan who fought for Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1649 and 1658.

Colonel Thomas Birch | |

|---|---|

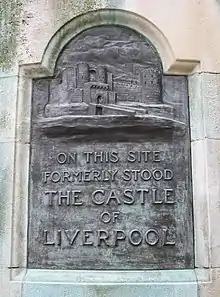

Plaque marking Liverpool Castle; Birch was Governor 1644 to 1655 | |

| MP for Liverpool | |

| In office September 1656 (not allowed to take his seat) – February 1658 | |

| Governor of Liverpool | |

| In office 1644–1655 | |

| Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire | |

| In office June 1642 – July 1650 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 June 1608 Birch Hall, Rusholme |

| Died | 5 August 1678 (aged 70) Liverpool |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse | Alice Brooke (died 1697) |

| Relations | Colonel John Birch (1615–1691) |

| Children | Five sons, five daughters |

| Parent(s) | George and Ann Birch |

| Occupation | Puritan radical, soldier, landowner |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1642 to 1660 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars |

|

Part of a large Puritan family, many of whom also served in the Parliamentarian army, Birch helped secure Lancashire for Parliament during the First English Civil War. He was appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire in 1642 and Governor of Liverpool in 1644. Unlike many of his colleagues, who were moderate Presbyterians, Birch was associated with the religious Independents who included Oliver Cromwell.

As a result, when the Commonwealth of England was established after the Execution of Charles I in January 1649, Birch became the leading political figure in Lancashire. However, he gradually came to oppose Cromwell, and was removed as Governor in 1655, as well as being excluded from the Second Protectorate Parliament. Following the 1660 Stuart Restoration, he retired from public life and lived quietly in Liverpool, where he died on 5 August 1678.

Personal details

Thomas Birch was born around 5 June 1608 in Birch Hall, Rusholme, now part of Manchester, eldest son of John Birch (1581–1611) and Anne Hey. He also had a sister, Anne.[1] His father died in 1611 when he was three years old; in 1641, his property was assessed as bringing in £250 per year, a substantial sum for the period.[2]

In 1623, he married Alice Brooke (died 1697); their ten children included five sons, Thomas (1629–1700), George (died after 1697), Matthew, Andrew (1652–?) and his twin Peter (1652–1710), who later became a Tory and Church of England priest.[3] Their five daughters were Anne, Alice, Mary, Elena, and Deborah (died after 1710).[4]

Career

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Little is known of his career prior to the outbreak of the First English Civil War in 1642; he had numerous relatives in the Manchester area, mostly Presbyterians who supported the Parliamentarian cause, including Colonel John Birch. Although North-West England was largely Royalist, Manchester was a Parliamentarian stronghold; in June 1642, Birch was named Deputy Lieutenant of Lancashire and raised a regiment of infantry.[2]

One of the first clashes of the war took place on 15 July when the Earl of Derby, Royalist leader in the North-West, tried to capture the arms store at Manchester. He was repulsed by Birch, beginning a rivalry which lasted until the Earl's death in 1651.[5] When Derby besieged Manchester on 26 September, Birch was part of the garrison that held out until the Royalists retreated on 1 October, a victory that boosted Parliamentary morale in the area.[6]

In December, he was promoted major in a regiment commanded by Colonel Ralph Assheton, MP for Liverpool in the Long Parliament. He was present at the capture of Preston in February 1643, a significant victory that isolated Royalist forces in North-East Lancashire. One of his colleagues was George Booth, who later led Booth's Uprising in 1659.[7]

In 1643, Birch was appointed to the Lancashire Sequestration Committee, responsible for imposing fines on Royalists, and also colonel of a regiment of infantry in the Northern Association.[8] He was made governor of Liverpool in June 1644, shortly before it was taken by Prince Rupert on his march north. Defeat at the Battle of Marston Moor in July cost the Royalists the North-West; Liverpool was retaken in November and Birch was given a garrison of 600 to hold the port.[9] His regiment took part in the June 1646 siege of Goodrich Castle, one of the last actions of the First Civil War.[8]

Victory exacerbated divisions within Parliament; most of the leadership in Lancashire were moderate Presbyterians, among them Ralph Assheton, Alexander Rigby, Richard Standish and Sir Richard Hoghton. They were concerned by the radicalism of the religious Independents who dominated the New Model Army, such as Congregationalists like Oliver Cromwell and Thomas Birch.[2] However, when the Second English Civil War began in 1648, the Lancashire leaders remained loyal to Parliament and fought at Preston in August. The Earl of Derby still held the Isle of Man for Charles I; Birch arrested his two daughters and held them in Liverpool Castle as a guarantee for his good behaviour.[2]

The breaking point for many moderates was the decision to put Charles I on trial for treason, followed by his execution on 30 January 1649. Along with his cousin John, Sir Richard Wynn, MP for Liverpool, was excluded by Pride's Purge in December 1648; Assheton, Rigby, Sir Richard Hoghton, and others were dismissed from the army following the 1650 Militia Act. Birch was one of the few who retained their positions, replacing Wynn as MP for Liverpool in October 1649, and being appointed colonel of the Lancashire militia; for the next few years, he was the senior government officer in the region.[2]

When a Scottish army invaded England in 1651 during the Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652), the Earl of Derby landed in Lancashire planning to link up with Charles II at Worcester. Supported by Birch, a detachment of the New Model under Colonel Robert Lilburne scattered Derby's troops at Wigan Lane on 25 August. Although the Earl escaped, he was taken prisoner after the Battle of Worcester in September, and executed; Birch and Robert Duckenfield were sent to secure the Isle of Man, which they completed by early November.[10]

Post-1651

Although Liverpool was not represented in the 1653 Barebones Parliament, Birch was re-elected as MP in the First and Second Protectorate Parliaments. The latter was reluctantly called by Cromwell, largely to approve taxation for the army; along with Shuttleworth and Sir Richard Hoghton, both purged in 1648, Birch was one of the Lancashire MPs excluded from Parliament under Article VII of the 1653 Instrument of Government for opposing these measures.[11]

This indicated Birch was now aligning with his former colleagues, and he was not elected to the 1659 Third Protectorate Parliament. Commitment to the Commonwealth was partially the product of his religious radicalism, but it became clear he was moderating his views in this area as well. In 1649, he confiscated a building previously occupied by the Collegiate church of Manchester; in 1653, Humphrey Chetham, a wealthy Presbyterian merchant, left money in his will for this to be turned into a charity school, now Chetham's School of Music. In 1656, Birch ensured the appointment of Presbyterian Henry Newcome as minister of what is now Manchester Cathedral.[12]

In 1658, Cromwell died and was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell, who resigned in May 1659. Increasing political instability led to Booth's Uprising in August, an attempt to restore Charles II led by Sir George Booth, who fought with Birch during the First English Civil War. Mainly confined to Cheshire, the revolt was quickly defeated by General Lambert, although its leaders escaped punishment. Birch remained neutral, although Henry Newcome urged his congregation to join the rising, while Liverpool declared its support for Booth.[13]

Birch was clearly seen as sympathetic since shortly before The Restoration in May 1660, the new commander-in-chief, George Monck, made him colonel of Lambert's former regiment.[14] After Charles returned, Birch retired into private life; his past radicalism meant he was suspected of involvement in a 1663 republican conspiracy, but there was no evidence to support the claim.[2]

He may have been protected by his cousin John and other acquaintances who were MPs in the Cavalier Parliament. He complied with the 1662 Act of Uniformity requiring membership of the Church of England, although he continued to support Non-conformist priests at Birch Chapel. One of these was Henry Finch (1633–1704), a celebrated Presbyterian preacher. He died at home in Liverpool on 5 August 1678.[2]

References

- Booker 1859, p. 87.

- Whitehead 2004.

- Cornwall 2004.

- Booker 1859, p. 102.

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 106–107.

- Irving 2009.

- Broxap 1910, p. 65.

- Colonel Thomas Birch’s Regiment of Foot.

- Broxap 1910, p. 137.

- Broxap 1910, p. 210.

- Gaunt 1997, p. 192.

- Blackwood 1979, p. 75.

- Blackwood 1979, p. 76.

- Colonel John Bright’s Regiment of Foot.

Sources

- Blackwood, B.G. (1979). The Lancashire Gentry and the Great Rebellion, 1640–60. Manchester University Press.

- Booker, John (1859). A History of the Ancient Chapel of Birch, in Manchester Parish; Volume XLVII. Chetham House.

- Broxap, Ernest (1910). The Great Civil War in Lancashire. Manchester University Press.

- Colonel John Bright’s Regiment of Foot. "Colonel John Bright's Regiment of Foot". BCW Project. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Colonel Thomas Birch’s Regiment of Foot. "Colonel Thomas Birch's Regiment of Foot". BCW Project. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Cornwall, Robert (2004). "Birch, Peter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2432. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gaunt, Peter (1997). Oliver Cromwell: Historical Association studies. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631204800.

- Irving, Sarah (5 October 2009). "The Siege of Manchester, 1642". Radical Manchester. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1958). The King's War, 1641–1647 (1983 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140069914.

- Whitehead, David (2004). "Birch, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66520. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)