Thomas Cheney

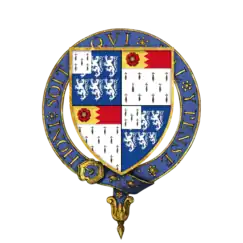

Sir Thomas Cheney (or Cheyne) KG (c. 1485 – 16 December 1558) of the Blackfriars, City of London and Shurland, Isle of Sheppey, Kent,[1] was an English administrator and diplomat, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in south-east England from 1536 until his death.

Early life

Thomas Cheney, born about 1485, was the son of William Cheney (d.1487) of Shurland Hall near Eastchurch, in the Isle of Sheppey, Kent, Constable of Queenborough Castle and Sheriff of Kent in 1477, by his second wife, Margaret Young.[2]

Thomas Cheney's father, William, was the eldest surviving of eight sons and a daughter, and at his death in 1487 his property in Kent was inherited by Francis Cheney (d.1512), his son and heir by his first marriage, but was in the possession of Francis Cheney's uncle, John Cheyne, Baron Cheyne until the latter's death without issue in 1499. Baron Cheyne's heir, his brother, Robert Cheney, died without issue in 1503, at which time Francis Cheney 'wrongfully took possession of their lands in Berkshire and Kent which should by an earlier settlement have passed to John, the son of a younger brother Roger'. Francis Cheney died without issue in January 1512, and Thomas Cheney succeeded to his father William's lands; however the other properties wrongfully acquired by Francis Cheney were awarded in 1515 to his cousin, John son of Roger Cheyne (d. 1499) of West Woodhay, Berkshire.[3]

Career

Cheney was appointed Sheriff of Kent in 1515,[3] and was Justice of the Peace for Kent from 1526 until his death.

He was a favourite of Henry VIII's mistress, Anne Boleyn, and she fought Cardinal Wolsey for his promotion in 1528 and 1529, although he later participated in bringing her down. However, it was not until 1535–40 that Cheney consolidated his authority as one of the most powerful men in the south-east of England. From Henry VIII's coming to the throne of England in 1509, Cheney served as Lord Warden, spanning the reigns of all five of the Tudor monarchs. Cheney was present at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, and served three times as an ambassador to France, under the authority of Henry VIII and Charles V of France, between 1549 and 1553. He was Treasurer of the Household from early 1530, and he is recorded as being present at over half of the Privy Council meetings held between 1540 and 1543.

He represented Kent as a knight of the shire in every parliament from 1539 to 1558 with the single exception of the election in 1555.

Cheney was among those councillors entrusted with the government of the realm during Somerset's Scottish campaign of 1547. He was among those who sanctioned Gardiner's imprisonment in June 1548, and he was involved in the interrogation of Sir Thomas Seymour in 1549.

In 1550, he became a privy counsellor and owner of the Manor of Ospringe (in the parish of Faversham).[4]

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

As the Constable of Saltwood Castle (near Hythe), Queenborough Castle (in Sheppey), Rochester Castle and Dover Castle, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Lord Lieutenant of Kent (1551–3), Thomas Cheney was much 'involved with musters and coastal defence'. Sir Thomas Cheyne was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports on 17 May 1536 and appears to have been deprived of the office soon after Edward VI's accession, but was granted it back to him the following April.

In April 1545 Cheney suffered a bout of illness, and was temporarily replaced in his duties as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports by Sir Thomas Seymour, Hertford's brother. For the next four months Cheney delegated his responsibilities in the Cinque Ports and Kent to Seymour.

Reign of Mary I

Cheney opposed the plan to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne, and although he acquiesced with Northumberland's policy, he pledged his support for Mary I as soon as he felt it safe so to do. Mary sent him as ambassador to Charles V at Brussels in August 1553 to announce her accession to the throne. He was known by the title of his office as "Lord Warden".[5]

In January 1554, Cheney gathered a force in Kent to resist Wyatt's rebellion.[6] In London, there was a rumour that he held Dover Castle for the rebels.[7] So fickle a courtier was he that the Marian Court privately distrusted his loyalty during the outbreak of the rebellion by his friend and neighbour Sir Thomas Wyatt, but the very fact that he sent men against Northumberland indicates something of his position.[8] Cheney was initially distrusted by Mary, as she confessed to the imperial ambassador Simon Renard. His early show of support proved shrewd as Cheney retained his position as Treasurer of the Household whilst other household officers were replaced.[9]

Death

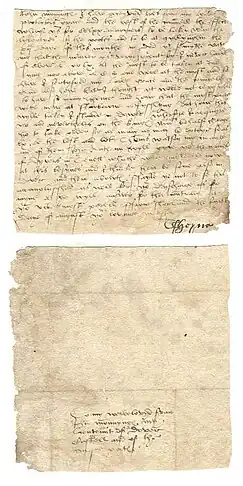

Cheney died on 16 December 1558 at the Tower of London,[2] and was buried on 3 January 1559 in St Katherine's chapel of Minster Abbey on the Isle of Sheppey.[10] He was survived by his son, Henry, and three daughters, Anne, Frances and Katherine.[2] His will and the elaborate proceedings at his funeral were entirely consistent with the orthodox Catholicism of the period, showing him to have been conservative. In his will dated 6 December 1558,[11] Cheney mentioned various properties which together gave him an annual rent of over £950, and after his death it was estimated that he maintained between 200 and 300 servants and retainers.

Marriages and issue

Cheney married firstly, by 1515, Frideswide Frowyk (died c. 1528), the daughter of Sir Thomas Frowyk,[12][13][14][15] by whom he had a son and three daughters:[2]

- John Cheney, who predeceased his father

- Anne Cheney (d. 1553), who married Sir John Perrot, Lord Deputy of Ireland

- Frances Cheney (d. 1561), who married Nicholas Crispe (d. 1564)[16][17]

- Katherine Cheney (d. before 1550), who married Sir Thomas Kempe (d. 7 March 1591) of Olantigh in Wye, Kent, by whom she had three daughters, Margaret Kempe, who married William Cromer (d. 12 May 1598); Anne Kempe, who married Sir Thomas Shirley, and Alice Kempe, who married firstly Sir James Hales (d. 1589), grandson of Sir James Hales (d. 1554), and secondly Sir Richard Lee (d.1608), illegitimate half-brother of Queen Elizabeth's champion, Sir Henry Lee[18][19][20]

According to Lennard, Anne, Frances and Katherine were all daughters of Cheney's first marriage:[21]

Sir Henry Cheyne, knight, summoned in 1572 as Lord Cheyne of Toddington, died s.p. in 1587, having wasted his estate. His three half-sisters, daughters of the first marriage of his father Sir Thomas Cheyne of Sheppey, K.G., were his coheirs. Anne Cheyne, the third of these, was the first wife of Sir John Perrot, the lord deputy of Ireland, and mother of Sir Thomas Perrot his heir. Sir John Perrot, who was reckoned a bastard son of Henry VIII., died in 1592.

Cheney married secondly, by dispensation dated 24 May 1539, Anne Broughton (d. 16 May 1562), stepdaughter and ward of John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, and daughter of Sir John Broughton (d. 24 January 1518).[22][23] of Toddington, Bedfordshire, by Anne Sapcote (d. 14 March 1559), and granddaughter of Sir Robert Broughton by his first wife, Katherine de Vere, said to have been the illegitimate daughter of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford,[24][3] by whom he had a son, Henry Cheyne, 1st Baron Cheyne of Toddington, and a daughter.[2] There is a monument to Cheyney's second wife at Toddington.[25][26]

References

- "CHEYNE, Sir Thomas (1482/87-1558), of the Blackfriars, London and Shurland, Isle of Sheppey, Kent. | History of Parliament Online".

- Lehmberg 2004.

- Cheyne, Sir Thomas (1482/87-1558), of the Blackfriars, London and Shurland, Isle of Sheppey, Kent, History of Parliament Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Hasted, Edward (1798). "Parishes". The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent. Institute of Historical Research. 6: 499–531. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, 'Vita Mariae Reginae of Robert Wingfield', Camden Miscellany, XXVIII (London, 1987): Royall Tyler, Calendar State Papers, Spain, 1553 (London, 1916), pp. 181-2: Charles Cooper, Appendices to a Report on Thomas Rymer's Foedera (London, 1869), p. 338.

- David Loades, Two Tudor Conspiracies (Cambridge: CUP, 1965), pp. 63–44.

- John Gough Nichols, Chronicle of Queen Jane (London: Camden Society, 1850), p. 36.

- David Loades, Two Tudor Conspiracies (Cambridge: CUP, 1965), pp. 83–84.

- David Loades, The Reign of Mary Tudor: Politics, Government and Religion in England 1553-58 (Longman, 1979), p. 42.

- "Abbey - Minster Abbey". www.minsterabbey.org.uk.

- Mayer 2008, p. 132.

- Doe 2004.

- Blaydes 1884, p. 14.

- "Inquisitions: Henry VII", Abstracts of Inquisitiones Post Mortem for the City of London: Part 1 (1896), pp. 5–27 Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- 'Parishes: Shalbourne', A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 4 (1924), pp. 228–234 Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Crispe, Nicholas (by 1530–64), of Whitstable, Kent, History of Parliament Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Parishes: Shalbourne', A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 4 (1924), pp. 228–234 Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Richardson I 2011, p. 327.

- Richardson III 2011, p. 276.

- Chambers 1936, p. 23.

- Lennard 1904, p. 200.

- Copinger 1910, pp. 156, 319.

- Anne Sapcote (d. March 1558/9), A Who’s Who of Tudor Women: Sa–Sn compiled by Kathy Lynn Emerson to update and correct Wives and Daughters: The Women of Sixteenth-Century England (1984) Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Blaydes 1886, p. 187.

- Pollard 1901, p. 422.

- Nichols 1846, p. 156.

- 'Willesden: Manors', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7: Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden (1982), pp. 208–216. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

Sources

- Blaydes, Frederic Augustus, ed. (1886). "Loring Family of Chalgrave". Bedfordshire Notes and Queries. Bedford: Arthur Ransom. I: 187. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Blaydes, Frederic Augustus (1884). The Visitations of Bedfordshire. Vol. XIX. London: Harleian Society. p. 14. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Chambers, E.K. (1936). Sir Henry Lee; An Elizabethan Portrait. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Copinger, W.A. (1910). The Manors of Suffolk. Vol. 6. Manchester: Taylor, Garnett, Evans and Co. Ltd. pp. 156, 319. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Doe, Norman (2004). "Frowyk, Sir Thomas (c.1460–1506)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10206. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lehmberg, Stanford (2004). "Cheyne, Sir Thomas (c.1485–1558)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5263. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lennard, T. Barrett (1904). Barron, Oswald (ed.). "Sir Francis Barnham". The Ancestor. Westminster: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. (IX): 191–209. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Mayer, Thomas F. and Courtney B. Walters (2008). The Correspondence of Reginald Pole. Vol. IV. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 132–3. ISBN 9780754603290. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Nichols, John Gough, ed. (1846). "A Summary Catalogue of Monumental Art Existing in Parish Churches: Bedfordshire". The Topographer and Genealogist. London: John Bowyer Nichols and Son. I: 154–60. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1901). "Cheyne, Thomas". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1901 supplement. pp. 421–3. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City, Utah. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. p. 276. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. p. 276. ISBN 978-1449966393.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)