Thomas Embling

Thomas Embling (26 August 1814 – 17 January 1893) was a doctor from the United Kingdom who took an interest in the humane treatment of inmates in asylums before emigrating to Melbourne, Australia where he set about reforming the Yarra Bend Asylum. Later on Thomas Embling took up the cause of the gold miners in Eureka and had a successful career in the early parliament of Victoria.

Thomas Embling | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 August 1814 Oxford, England |

| Died | 17 January 1893 (aged 78) Hawthorn, Melbourne, Australia |

| Years active | 1837–1893 |

| Known for | Pioneer in ethical treatment of the mentally ill |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Medical Officer, General Practitioner, politician |

| Institutions | Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum |

| Sub-specialties | Treatment of mental illness |

Early life

Thomas Embling was born 26 August 1814 in Oxford, United Kingdom.[1] At 16 he was apprenticed to an apothecary.[2] He then studied medicine, becoming a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1837 and a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries in 1838.[3]

After his graduation in 1829 he went into partnership in practice with his brother. It was during this time he held a position as a Visiting Medical Officer at Hanwell Asylum,[4] where he became familiar with the latest treatment methods in lunatic asylums.[5] Embling married Jane Webb Chinnock on 1 August 1839[1] and by 1841 they were living with their son, William on Brompton Row, South Kensington, London.[6] Both Embling and his wife suffered from 'pulmonary affections' which influenced their decision to emigrate to Australia.[3] In 1850 Embling, his wife and seven children[7] sailed from England to South Australia; they then travelled across to Melbourne. The journey to Melbourne was not without incident and Embling was caught up in the bush fires of Black Thursday in February 1851.[8]

Yarra Bend Asylum

Embling's first appointment in Australia was to be as an assistant to the Colonial Surgeon of Victoria. However parliament members James Johnston and Charles Ebden put forward the proposition that Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum required a Resident Medical Officer and Embling was highly suitable.[5] Although not a psychiatrist, Embling had a pioneering interest in the 'moral treatment' of mental illness[7][9]

Embling's early days at Yarra Bend were not easy. Superintendent George Watson was not pleased with the appointment of a Resident Medical Officer. With the assistance of displaced Visiting Medical Officer Dr Cussen,[4] Watson attempted to thwart Embling's efforts to become involved in the care of inmates. He was refused a pass key and denied access to many of the asylum buildings, including the accommodation that he was to have been provided on the asylum grounds. Efforts to hinder Embling however, only served to strengthen his resolve to become actively involved in the clinical management of his patients.[7] What he saw at Yarra Bend shocked him, his first impressions "were those of great astonishment not unmixed with pain … I saw much that was incomprehensible, and much disreputable."[3]

Despite the obstacles he encountered, Embling implemented significant reforms in a short space of time. He ordered the removal of manacles, camisoles and restraining gloves and rejected the then popular psychiatric practice of punitive "treatment".[7] These reforms were not popular with the Superintendent, nor with the colonial surgeon.[3] He was subsequently charged and brought before a disciplinary hearing, on the grounds that he was "too heroic to be a medical officer".[7]

Parliamentary enquiry

Aware that his accusers were highly regarded by the government, Embling briefed supportive parliamentarian James Johnston on the activities and corruption he had witnessed at Yarra Bend.[10] The story was picked up by the press, and in April 1852, only four months after Embling's appointment, The Argus newspaper called for a reorganisation of the asylum. Public support for an enquiry grew,[7] and following a motion put by Johnston in July 1852, a Select Committee was appointed "To Enquire into the Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum and to take Evidence".[10]

The committee sat from August to December 1852,[7] with the final report[11] citing evidence of mismanagement and human rights abuses including

- Evidence of physical and sexual abuse;

- Corruption;

- Poor treatment of inmates, including forcing 28 people to share the same bath water,

- Illegal use of asylum resources, including using resources supposedly earmarked for patients being funnelled into a private poultry farm run by the Superintendent;

- Patients being frequently drunk.[12]

The Committee found that patients had been severely maltreated and that the Superintendent was "grossly negligent as well as highly culpable". Praise was heaped upon Embling by the Committee, declaring "it is with extreme regret we observe the efforts of this gentleman to promote the efficiency of a valuable institution, and to check the abuses that so seriously affected its usefulness…"[13]

Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe dismissed the entire staff of Yarra Bend, including Embling. Superintendent Watson was given another post which led to The Argus launching a bitter attack on La Trobe, stating that Embling had been "turned adrift".[14] Embling wrote a comprehensive account of his experiences at Yarra Bend Asylum which The Argus published.[2] Despite the outcry against Embling's dismissal, Dr Robert Bowie was appointed as the first Medical Superintendent at Yarra Bend[15] and Embling set up a private practice in Gore Street, Fitzroy, Melbourne.[3][16]

Politician

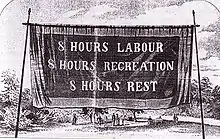

Embling publicly supported the popular movement at the Eureka Stockade near Ballarat in December 1854 and took over the chair at a public meeting which passed resolutions in favour of the gold miner's cause.[3] In 1855, he supported the eight-hours labour movement and is credited with coining the slogan, 'Eight hours labour, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest'.[3]

Embling was elected to the old unicameral Victorian Legislative Council for North Bourke in September 1855, holding this seat until the Council ceased in March 1856.[1] It was during this time that Embling was able to use his experience in the workings of lunatic asylums as he sat on an Asylum Board of Enquiry.[14] Embling later was elected as a member of the newly created Victorian Legislative Assembly for the seat of Collingwood in November 1856, becoming a founding member of the Assembly. He served in the seat until July 1861 and again from February 1866 to December 1867.[1] Following disagreements with his fellow politicians[3] and poor health[7] Embling withdrew from politics in 1869 and resumed his general medical practice.

Zoological Society and the acclimatisation of animals

Embling was a strong advocate of the introduction of exotic animals into Victoria. In 1856 he lobbied parliament for the introduction of alpacas. In 1858 he proposed importing camels for use in desert exploration and he spoke at length in Parliament and in the Melbourne press on the subject. He supported the establishment of the Zoological Society and proposed that George James Landells be sent to India to purchase camels.[17] The camels Landells returned with were used on the Burke and Wills expedition in 1860.[18]

Death and commemoration

Thomas Embling died of "Senile Debility" on 17 January 1893 survived by his wife and four children.[3]

In April 2000 'Thomas Embling Hospital' was opened. Built adjacent to the site of the original Yarra Bend Asylum, Thomas Embling Hospital is operated by the Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health and is a secure hospital for patients from the criminal justice system who are in need of psychiatric assessment, care and treatment.[19]

Notes

- Parliament of Victoria, Re-Member Database "Embling, Thomas". Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Evans, Alicia (1998), The case for "The Embling Hospital"

- Kennedy, Richard (1972). "Embling, Thomas (1814–1893)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Bonwick, p.31

- Brothers, p.21

- 1841 UK Census

- Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health (May 2009). Forensicare Orientation Handbook. VIFMH. p. 31.

- Mennell, Philip (1892). The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. Hutchinson & Co. p. 149.

- "moral treatment" was supposed to be the foundation of treatment at Yarra Bend, as specified in the "Regulations for the Guidance of Officers, Attendants and Servants of the Lunatic Asylum at Port Phillip" (later known as Yarra Bend), published in the Government Gazette of 1849.(Brothers, p.19)

- Brothers, p.22

- Johnston, James; et al. (1852). Report from the Select committee of the Legislative Council on the Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum: together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendix. Melbourne: Government Printer.

- "Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum (1848 - 1925)". Darebin Historical Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Bonwick, p.33

- Brothers, p.26

- Brothers, p.27

- Australian Electoral Rolls 1856, Victoria

- Bonyhady, Tim (1991). Burke and Wills: From Melbourne to Myth. David Ell Press. ISBN 0-908197-91-8.

- Phoenix, Dave. "Burke & Wills Web; Camels & Sepoys for the Expedition". Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- VIFMH. "Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health – general brochure" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

References

- Bonwick, Richard (1995). "The History of Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum, Melbourne".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Brothers, C.R.D (c. 1959). Early Victorian Psychiatry: 1835 - 1905. A.C. Brooks.