Thomas G. Jones

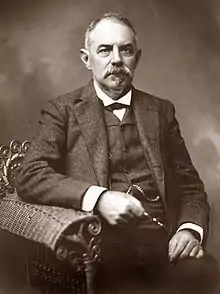

Thomas Goode Jones (November 26, 1844 – April 28, 1914) was an Alabama lawyer, politician, and military officer. He served in the Alabama legislature and as Governor of Alabama. He later became United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama and the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama.[1]

Thomas Goode Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama | |

| In office December 17, 1901 – April 28, 1914 | |

| Appointed by | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | John Bruce |

| Succeeded by | Henry De Lamar Clayton Jr. |

| 28th Governor of Alabama | |

| In office December 1, 1890 – December 1, 1894 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Seay |

| Succeeded by | William C. Oates |

| Member of the Alabama House of Representatives | |

| In office 1884-1888 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thomas Goode Jones November 26, 1844 Macon, Georgia |

| Died | April 28, 1914 (aged 69) Montgomery, Alabama |

| Education | Virginia Military Institute read law |

| Signature | |

Family and early life

He was born on November 26, 1844, in Vineville (now Macon, Georgia) to Martha Goode (1821–1861) and her husband, railroad builder Samuel Jones (1815–1886), who had moved to Georgia in 1839 to become an assistant engineer on the Monroe Railroad, which soon declared bankruptcy. Despite financial problems around Thomas's birth, Samuel Goode would become an engineer on various other railroads in Alabama and Florida, one of Alabama's early industrialists, and briefly, an Alabama legislator representing Lee County, Alabama.

He also remarried during the Civil War to Aurora Serena Elmore, who was descended from Representative Joseph Brevard of South Carolina and would bear seven boys (Thomas's step-brothers) during their marriage.

Shortly before the war began, Samuel Jones completed the Alabama and Florida Railroad, which supplied the Confederate Navy Yard in Pennsacola. He also helped establish the Chewacla Lime Works, the Montgomery and Talladega Sulphur Mines, and the Muscogee Lumber Company and completed a railroad line connecting Montgomery and Selma, Alabama, shortly before the Civil War ended, and then the Savannah and Memphis Railroad.[2]

Even more than the Jones family, the Goodes were among the First Families of Virginia. John Goode had arrived in Virginia via Barbados before 1661 and established a tobacco plantation in Henrico County. His descendant Samuel Goode, of Chesterfield County, served as a lieutenant during the American Revolutionary War and as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and the US House of Representatives. His son Thomas Goode (1787–1858), Martha's father, helped establish the Homestead European-style spa in Wythe County, Virginia.[3]

The Jones traced their descent from Captain Roger Jones, who commanded a British naval vessel in Chesapeake Bay in 1680 and whose youngest son, Thomas, settled near Fortress Monroe in what became Brunswick County, Virginia. Thomas's descendant John Jones represented Brunswick County in the Virginia House of Burgesses and became a captain in a Virginia regiment during the American Revolutionary War. His son Dr. Thomas Williamson Jones (1788–1824), graduated from the University of North Carolina before he married Mary Armistead Goode. Their eldest son, Samuel Goode Jones, studied at Williams College in Massachusetts and at Newark College (now the University of Delaware) before he married Martha Goode. In 1849, Samuel Jones moved his young family to Montgomery, Alabama, while he was the Montgomery and West Point Railroad engineer.[4]

Thomas had a sister, Mary, who had been born in Atlanta in 1847 and would have five more siblings who survived infancy before the Civil War began and seven half-brothers from his father's second marriage. In any event, he was not educated at home but was sent to Charlottesville, Virginia, to study at a preparatory academy by Charles Minor and Gessner Harrison. In the summer of 1860, he began to attend the Virginia Military Institute, and fellow cadets elected him as a sergeant.[5]

During the Civil War, in winter quarters in Petersburg, Virginia, Jones had begun studying William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. After the war, he failed as a planter. He clerked for the Alabama and Florida Railroad, and thanks to his father, Jones read law with John A. Elmore and then in a night class with Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Abram J. Walker.[6]

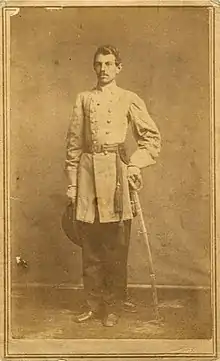

Military career

South Carolina declared secession from the United States before Jones's first semester ended. On May 1, 1861, after Virginia's secession vote, about 200 cadets (including Jones) joined Professor and Major General Stonewall Jackson in fighting for the Confederate States Army. Jones later recalled that his first duty was burying the dead after the Battle of McDowell. The cadets marched with Jackson's men until May 16, 1861, when the school summoned them back and later awarded them honorary degrees. Meanwhile, Jones returned to Montgomery and enlisted as a private in the Partisan Rangers, Company K of the 53rd Alabama Regiment, but he was soon promoted to sergeant. The unit fought at the Battle of Thompson's Station, in Tennessee, and Jones received a lieutenant's commission after he had led the unit despite his battle wound; both the company's captain and lieutenant had been wounded and abandoned the field.

Jones was appointed aide de camp to General John Brown Gordon and accompanied the Army of Northern Virginia during the Gettysburg Campaign, including as a messenger when Gordon requested permission to attack Cemetery Ridge but was denied during the Battle of Gettysburg. Jones also fought in the Siege of Petersburg, the Battle of the Wilderness, and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Jones also fought with Gordon during Jubal Early's campaign that reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C., and at the defeats during the Third Battle of Winchester and the Battle of Cedar Creek in late 1864. During the Battle of Cedar Creek, both sides respected Jones's courage in rescuing a girl caught in the crossfire between armies. He also received praise for rescuing a wounded Ohio soldier. Thus, Jones fought in the Confederate States Army from 1862 to 1865, rising to major. On April 9, 1865, he physically carried the truce flag on his sword while under fire, delivering Lee's surrender, and he witnessed the final ceremony at Appomattox Court House.[7]

Postwar career and politics

Returning from the Civil War, Goode claimed an inheritance from his mother and purchased 750 acres in southern Montgomery County, Alabama in 1865. Still, he failed as a farmer and moved in with his mother-in-law in Montgomery by 1869. Crushing debts, low cotton prices, and Black Friday would cause him to lose the farm in 1870.

Meanwhile, Jones became editor of the Montgomery Daily Picayune and read law in 1868, which helped his transition to his later career. Admitted to the Alabama bar in 1868, Jones began a private legal practice in Montgomery. Until November 1868, Jones worked as a lawyer and editor with Judge Walker's brother, Hal Walker. The Daily Picayune allied with the Democratic Party, decried "Negro rule," and proposed racial segregation although, unlike more radical newspapers, it also advocated educating black children. Jones also became children in the local Democratic Party, initially opposing groups allegedly trying to prevent the counting of votes for Democrat Robert B. Lindsay for governor. However, others characterize such efforts as intimidating black voters. Democrats ended Republican rule in Alabama in 1874, after an election in which Jones led about 100 armed Democrats who patrolled Montgomery on Election Day to intimidate Republican voters.[8] Jones' appointment as the reporter of decisions for the Supreme Court of Alabama by Chief Justice Elisha Peck also helped sustain his legal practice from 1870 to 1880.[9]

By 1874, Jones joined a law firm with former Alabama Chief Justice Samuel F. Rice, despite Rice's alliance with the Republican Party during Reconstruction. However, he resigned during a depot dispute between Montgomery and Rice's client, the South and North Alabama Railroad. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad later became one of Jones' major clients, including the Capitol City Water Works Company, Western Union Telegraph Company, Southern Express Company, and the Standard Oil Company.[10] By 1898, Jones partnered with his half-brother Charles Pollard Jones.[11]

Jones also wrote one of the earliest codes of legal ethics in 1887, adopted by the Alabama Bar Association and incorporated into the American Bar Association Code of Professional Ethics in 1907.[6][12]

After the war, Jones helped organize the Alabama National Guard. However, his initial efforts to reorganize the Montgomery True Blues as the Governor's Guards ended up being disbanded by federal authorities in 1868.[6]

Jones often spoke for reconciliation between the United States and the formerly Confederate states, first at a Memorial Day address in 1874 that became widely republished nationwide, and newly elected Governor George S. Houston named Jones his aide-de-camp for military affairs by year's end. In 1877, the Grand Army of the Republic presented Jones with a gold medal for his peace efforts. He also spoke at Jefferson Davis's last visit to Montgomery in 1886 and gave Memorial Day addresses in Atlanta in 1887 and at the tomb of Ulysses Grant in New York City in 1902. In 1874, the Governor's Guards offered their services to Governor Houston, and in 1881, they were officially organized as Alabama state troops. In 1876, Jones resigned as aide de camp and became a captain of the Montgomery Greys. Four years later, the Second Regiment elected Jones as their commander. He oversaw their use, including saving a black man from lynching during the Posey Riot of December 1883 and a white man in Birmingham in December 1888.[13]

Jones ultimately sought political office as a Democrat. First, he served on the Montgomery City Council, representing Ward 4 from 1874 to 1884, when he won an election as a member of the Alabama House of Representatives, where he served from 1884 to 1888 when he declined to seek re-election. During his second term, he became its speaker (1886 to 1888) and advocated funding the state militia and creating the state capital complex to house state government records. To the surprise of some, given his railroad clientele, Jones also cast a tie-breaking vote making railroads liable for work-related injuries and opposed Governor Edward A. O'Neal's efforts to control the Alabama Railroad Commission. Instead of running for re-election to the legislature, Jones returned to private practice to raise funds to campaign for governor, which was successful. He defeated the farmer Reuben Kolb and several others in the Democratic convention after several ballots and Republican candidate Benjamin M. Long handily in the general election. Jones was the Governor of Alabama from 1890 to 1894.[14]

In his first two-year term as governor, Jones proposed a constitutional amendment to allow long legislative sessions and local communities to levy taxes to finance education and internal improvements. He also opposed contrivances to disenfranchise blacks, such as educational and property requirements, and he denounced proposals to limit tax revenues from white taxpayers for white schools as unconstitutional. Although by no means a racial-egalitarian, Jones also opposed Alabama's convict leasing system despite the propaganda that it helped establish white supremacy as well as a frugal state government[15] Ironically, Jones both assumed office during a strike by coal miners who opposed unfair competition from leased convicts, which he initially resolved with the United Mine Workers by appointing a health and safety commissioner, and ended his second term dealing with a strike by Birmingham miners against the Tennessee Coal Iron and Railroad Company in which he called out state troops after hiring of black scabs provoked violence; the strike was widened by Eugene V. Debs to join the Pullman Strike.[16]

Despite Seay's boasts after cutting state taxes, the state was also nearly bankrupt, and the legislature, during his second term, refused to increase corporate taxes, as Jones had suggested.

Politics proved tumultuous, and Jones's attempts at replacing his former political rival Reuben Kolb as agricultural commissioner in his first term nearly proved pyrrhic. The Alabama Supreme Court approved the governor's new agricultural commissioner appointee when Kolb refused to vacate at the end of his term, and Kolb ran as an independent for governor in the next general election and narrowly lost to Jones, just like in the Democratic primary, which Kolb attributed to Jones's over-representation in the state's Black Belt.[17]

Jones would continue to dispute Kolb's contention that the 1892 election had been stolen until his death. Alabama House Speaker Frank L. Pettus and Senate President John C Compton were also from the Black Belt and ignored Kolb's investigation request. Ironically, given his overt white supremacist language, Kolb's attempts to link his Farmers' Alliance with the Populist candidate for president, former U.S. Army General James B. Weaver, may also have doomed his candidacy, many Alabamians supporting neither the Republican presidential candidate, Benjamin Harrison nor Weaver.[18]

Two weeks after Jones announced that state troops would remain in Birmingham until the miners' strike ended, on August 8, 1894, Kolb again lost his bid to become Alabama's governor, this time to Democrat William Calvin Oates, who, unlike Jones, supported the convict leasing system.[19] Expenses incurred during his gubernatorial term would haunt Jones for the rest of his life.

Jones's life insurance went to pay off the mortgage incurred during his governorship. Thus, he did not challenge John Tyler Morgan for the US Senate seat but remained politically active in supporting US President Grover Cleveland. Jones became a Gold Democrat rather than supporting William Jennings Bryan, despite continued criticism from Kolb. However, the Gold Democrats got only 6,453 votes in Alabama, compared to Bryan's 107,137, and so Jones's political capital in the state also seemed to be finished.

Jones rehabilitated his political fortunes in 1897 by remaining in Montgomery, despite a yellow fever epidemic in the coastal South, his policies being fumigation, prompt burials, and a quarantine supported by armed guards. The 11 people who died in Montgomery were part of at least 71 in the whole state.

Federal judicial service

Jones received a recess appointment from President Theodore Roosevelt on October 7, 1901, to a joint seat on the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama and the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama vacated by Judge John Bruce. President Roosevelt nominated him to the same position on December 5, 1901. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on December 17, 1901, and received his commission the same day. His service terminated on April 28, 1914, because he died in Montgomery.[14]

Jones was considered a moderate during his time on the bench. He opposed labor unions but supported the 14th Amendment and was a friend of black leader Booker T. Washington, to whom Jones owed his appointment as a federal judge. Roosevelt, also a friend of Washington, asked him to name a Southern Democrat he thought would qualify as a federal judge. Washington endorsed Jones for that position.[20]

During his tenure, Judge Jones heard civil rights cases, took stands against lynching and refused to allow the state's convict lease system to become de facto slavery. Those stands became unpopular in the white community for holding that federal law permitted the protection of black people.[21]

Death and legacy

His health deteriorated during the seven years while he oversaw a case in which railroads contested new rates set by the Alabama legislature. It was twice addressed by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and had certiorari denied by the United States Supreme Court. In the winter of 1912–13, Jones contracted pneumonia and recovered in Florida.

Although he returned to his duties in Alabama by November 1913, he again soon took a leave of absence for health reasons. He had been bedridden for weeks before he lost consciousness on April 26, 1914, and died two days later.

Hundreds attended his funeral in Oakwood Cemetery, including many African Americans.[22]

References

- Aucoin, Brent J. (Brent Jude). Thomas Goode Jones : race, politics, and justice in the new South. Tuscaloosa. ISBN 978-0-8173-8988-8. OCLC 950884950.

- Aucoin pp. 12–13

- Aucoin p. 12

- Aucoin pp. 6–7.

- Aucoin p.7.

- "Thomas Goode Jones". Alabama Mens Hall of Fame.

- Aucoin pp. 8–11

- Aucoin pp. 13–15

- Aucoin pp. 51–52

- Aucoin p. 18

- Aucoin p. 96

- Aucoin pp. 19–20

- Aucoin pp. 15–17, 22

- Thomas Goode Jones at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Aucoin pp. 22–32

- Aucoin pp. 85–89

- Aucoin pp. 46–63

- Aucoin pp. 67–69

- Aucoin pp. 88, 92–93

- Named Judiciary, October 8, 1901. The Courier-Journal, page. 8

- Aucoin, Brent (2007). A Rift in the Clouds: Race and the Southern Federal Judiciary, 1900-1910. University of Arkansas Press.

- Aucoin pp. 166–168

Sources

- Thomas Goode Jones at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- "Thomas Goode Jones (1890-94)". Encyclopedia of Alabama.

- Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex, Random House, 2002, location 21341, Kindle Edition