Thomas Hoo, Baron Hoo and Hastings

Thomas Hoo (died 1455), was an English landowner, courtier, soldier, administrator and diplomat who was created a Knight of the Garter in 1446 and Baron Hoo and Hastings in 1448 but left no son to inherit his title.[1]

Having served in military command in Normandy, he assisted in the negotiations for peace with the King of France in 1442–1444, and was in personal attendance on Margaret of Anjou in France during the months preceding her marriage. A servant of the Lancastrian throne, by the death of his friend the Earl of Suffolk in 1450 he lost a distinguished patron.

Origins

Parents

He was the son of Sir Thomas Hoo (c. 1370-1420) of Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire (son of Sir William Hoo (1335–1410) and his first wife, Alice de St Omer), by his first wife, Eleanor de Felton (c. 1361 - 8 August 1400), whom he married in about 1395. Eleanor was the widow of Sir Robert de Ufford, de jure Lord Clavering (died c. 1393)),[2] and the youngest of the three daughters of Sir Thomas de Felton (died 1381), of Litcham, Norfolk,[3] Seneschal of Aquitaine, by his wife, Joan Walkefare. Baron Hoo had three Ufford half-sisters, from his mother's first marriage. Sir Thomas Hoo (born c. 1370) remarried to Elizabeth Echyngham (a daughter of Sir William Echingham (died 1413/14) of Etchingham, Sussex),[4] by whom he had a further son, Thomas Hoo (born 1416), "the younger", half-brother to Baron Hoo.[5][6]

Sir Thomas Hoo (c. 1370-1420), the father, distinguished himself at the Battle of Agincourt as a knight to Thomas de Camoys, 1st Baron Camoys, commander of the left wing of the English army.[7] In June 1420, Sir Thomas Hoo (c. 1370-1420), the father, and two others were entrusted to ensure the safe passage of the Duke of Bourbon to France, and in the August following, Sir Thomas died at his seat Luton Hoo. His widow, Elizabeth, remarried to Sir Thomas Lewknor (c. 1392–1452) of Horsted Keynes, as his second wife, and bore him further children.[8]

Baron Hoo succeeded his father, inheriting family estates including Luton Hoo, the St. Omer manor of Mulbarton in Norfolk, and that of Offley St Legers, Hertfordshire, which had been inherited by the Legers from the De la Mare family at about the end of the 12th century.[9]

Ancestry

The Hoo family was seated at Luton Hoo, Bedfordshire, by 1245.[10] The descent was as follows:

- Robert Hoo "The Elder". By the 1290s the marriage of Robert Hoo "The Elder" to Beatrix Andevill brought him the nearby manor of Knebworth in Hertfordshire[11] and other lands of the Andevill family:[12][13]

- Robert Hoo "The Younger", son, married Hawise FitzWarin,[14] a daughter of Fulk FitzWarin, 1st Baron FitzWarin (Fulk FitzWarin V) and widow of Ralph de Goushull,[15]

- Thomas Hoo, son of Robert Hoo "The Younger", was the great-grandfather of Baron Hoo and Hastings. In 1335 he married Isabel St Leger, a daughter of John St Leger. By this union, the manor of Offley St Legers, Hertfordshire, came to the Hoo family.[16] Thomas Hoo and Isabel St Leger were buried in St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire, to which they gave an altar-frontal cloth embroidered with the arms of Hoo and St Leger.[17][18]

- Sir William Hoo (1335–1410), son of Thomas Hoo and Isabel St Leger, married firstly Alice de St Omer (d.1375), a daughter and co-heiress of Thomas de St Omer (d.1364) of Mulbarton, near Norwich, in Norfolk, a Justice and Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk,[19] by his first wife Petronilla (or Pernell) Malemayns, a daughter of Sir Nicholas de Malemayns (d.1349), of Ockley in Surrey.[20][21] Alice de St Omer's share of her paternal inheritance included the manor of Mulbarton, which thus came to the Hoo family[22] Petronilla's sister Beatrice Malemayns married Otho II de Grandison, and has a monument in Ottery St Mary Church in Devon. Sir William de St Omer (father of Thomas) and his wife Elizabeth earned the lifelong gratitude of King Edward III for their part in safeguarding the Black Prince and his sisters at a time of danger in their childhood.[23] They were seated both at Mulbarton, and at Britford near Salisbury, Wiltshire (where Alice was born[24]), adjacent to Clarendon Palace. They were most likely the patrons of the "St Omer Psalter", a sumptuous but unfinished illuminated book made circa 1330s-1340s. Images of the patron, wearing a tabard displaying the St Omer arms, and his wife, appear in the embellishments to the grand initial of Psalm 1.[25]

- Blomefield (1807) stated that Sir William Hoo (1335–1410) was responsible for rebuilding the tower and nave of Mulbarton church and mentions that stained glass in a north window of the chancel showed, on one side, Sir Thomas de St Omer with his wife and daughter Alice de St Omer, kneeling, with the arms of St Omer and Malemayns: and, on the opposing side, Sir William Hoo and his wife Alice de St Omer, beneath the arms of Malemayns and St Omer. The Hoo arms appeared at the top of the window, and below was a prayer in Norman French: Priez pur lez almez Monsieur Thomas Sentomieris et Dame Perinelle sa femme qui fit faire ceste fenestre ("Pray for the souls of Thomas de St Omer and Dame Petronilla his wife, who had this window made").[26] Alice de St Omer died in 1375[27] and was buried at Mulbarton: the window, therefore, embodied the transition from St Omer to Hoo patronage. No recognizable parts of this window survive among the fragments of medieval glass now re-set at Mulbarton.[28]

- Sir William Hoo (1335–1410) married secondly Eleanor Wingfield, a daughter of Sir John Wingfield of Letheringham in Suffolk.[29] He later served as Captain of the Castle of Oye in the Marches of Picardy,[30] and at his death in 1410, aged 75, was buried at Mulbarton beside his first wife Alice de St Omer. He was survived by his widow Eleanor Wingfield.

Service

The first marriage of Thomas Hoo belonged to the first years of his majority as heir of Hoo, before he received the honours and titles associated with Hastings. He married Elizabeth, daughter of Nicholas Wychingham, Esquire (died 1433), of Witchingham in Norfolk,[31] and had by her one daughter, Anne, who was born circa 1424.

Thomas Hoo was Esquire of the Chamber to Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, and he probably went into France in 1419 as part of the Duke's retinue. In his master's will of 1426, he was left one of the Duke's coursers.[32] He was High Sheriff of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire in 1430.[33] In 1431 he was one of the feoffees to the estates of William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk.[34]

In 1435 he was deployed by Lord Talbot in suppressing a popular revolt in Normandy. The Normans of the Pays de Caux, heartened by the death of the Duke of Bedford (Regent of France), rose up, robbed many towns under English control, and captured Harfleur by assault, and other towns. Lord Talbot sent for Lord Hoo, Lord Scales and Sir Thomas Kyriell, who visited severe reprisals on that country, slaying more than five thousand people, burning the unfortified towns and villages, rounding up all the livestock and driving the rebellious inhabitants into Brittany.[35] In October 1435 Henry VI appointed Hoo to the office of Keeper of the Seals of France.[36] Hoo became Chancellor of France in 1443 after the death of Louis de Luxembourg, Bishop of Thérouanne[37]

In 1439 Hoo was in Lord Talbot's forces in the large expedition into France under Richard Duke of York, and was sent by his commander to the Captain at Mantes and to the Lieutenant at Pontoise, to strengthen the garrison of Vernon. He himself succeeded as Bailiff and Captain of Mantes in 1440 and 1441, until in November of the latter year replacing Neville, Lord Falconbridge as Captain of Verneuil and serving also as Master of Ostel. In January 1442 he went with François de Surienne to propose a scheme to capture the town and fortress of Gallardon: they were to pay for the men-at-arms and archers, and to provide 250 men each to the King's service, but if successful were to have command of the place and the division of the spoils, and Sir Thomas was to be reimbursed his expenses. By July 1442 the scheme had a successful outcome.[38]

In September 1442 he was appointed to the Embassy to negotiate peace with the French king, led by Richard Duke of York and Cardinal Louis (who was then in the capacity as Chancellor of France).[39] He was in a renewed commission under the Earl of Suffolk, appointed in February 1444, which concluded a truce at Tours which lasted until 1450.[40][41] In the course of these negotiations the marriage between Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou was arranged by the Earl of Suffolk, and in July 1444 Thomas Hoo was appointed, and in August sent with Sir Robert Roos and the Garter King at Arms, to be in attendance upon Margaret[42] until her landing in England in April 1445, when the marriage was solemnized. During the intervening period she was espoused to the king by proxy in the person of the Duke of Suffolk.[43]

Second marriage

The second marriage of Sir Thomas Hoo belonged to the period of his service in Hastings and Normandy, when he became titled. He married Eleanor Welles (one of the four daughters of Lionel de Welles, 6th Baron Welles and Joan Waterton, daughter and heiress of Robert Waterton (c. 1360–1425)), and they had three daughters, Anne, Eleanor and Elizabeth. These daughters were born between 1447 and 1451, as their ages are given in their father's inquisition post mortem.[44]

In November 1445, Leo Welles made a covenant with Sir Thomas and Eleanor, by which Thomas acknowledged Welles's right of gift, and Welles granted to them, and to their male heirs forever, the manors of Hoo, Mulbarton, Offley and Cokernho, and the advowsons of Mulbarton and Offley, with remainders (successively) to the male heirs of the body of Sir Thomas, or to Thomas Hoo his brother and to the male heirs of his body, or to the heirs of the body of Sir Thomas, or to the heirs of the body of Thomas Hoo, or (failing all these) finally to the right heirs of Sir Thomas. The lands brought by Sir Thomas to the marriage were thereby secured to the Hoo descent through either brother.[45] In 1447, Welles also remarried, to Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso.

- "The Hours of Thomas, Lord Hoo"

Important insights into the life and character of Lord Hoo are preserved in a Book of Hours which was made for him around 1444, probably as a gift for his wife Eleanor. It is a French production of 293 folios on vellum, made in Rouen, includes 28 colourful miniatures of religious subjects, and the text, which is of the Sarum Use and employs English, French and Latin, is decorated throughout with ornamental margins. All but one of the miniatures are by one artist, known (from this book) as the "Hoo Master", of which about half are devotional scenes and half narrative subjects. They include patron images (identifiable by heraldry): Lord Hoo prays to the Holy Trinity, a little preceding a scene of the disembowelling of St Erasmus, suggesting that he may have suffered from intestinal troubles. Dame Eleanor prays to the Virgin and Child, and wears a high butterfly headdress, and the arms of Hoo impaling Welles upon her kirtle: just after this, images of St Leonard and St Hildevert (Bishop of Meaux, died c. 680) are inserted, suggesting that she may have been afflicted by mental weakness or epilepsy.[46]

The volume's extensive texts include a unique collection of prayers of an anxious and penitent nature, possibly exemplifying episodes or responsibilities in Lord Hoo's own life. The inserted image of St Hildevert is the odd one out, being the work of the "Talbot Master" who illustrated the great "Shrewsbury Book" given by Lord Talbot to Margaret of Anjou as a wedding gift, a book which (conversely) includes one miniature by the "Hoo Master". Both artists (of whom the "Hoo Master" was notably more sophisticated in technique) were probably miniaturists of the Parisian school who had moved to work at Rouen. Other books illustrated by these artists exist, but the involvement of Lord Talbot and Lord Hoo in the wooing of Margaret d'Anjou reflects the context in which these two commissions were placed.[47]

Title

In June 1443, Hoo, "the King's knight", was awarded £40 a year for life, out of the revenues of Norfolk, "for many great and toilsome services in the wars in France, no small time".[48] On July 19, 1445[49] he was granted the castle, lordship, barony and honour of Hastings,[50] and in that year was elected and, in 1446, installed as Knight of the Order of the Garter.[51] He forthwith released Sir Roger Fiennes personally, and his manor of Herstmonceux in manorial duty, from feudal services due to the honour of Hastings (excepting fealty), renewing the awards made by his ancestor Sir John Pelham.[52]

In June 1448, he was created Lord Hoo and Hastings:

"Grant to Thomas Hoo in tail male, for good service in England, France and Normandy, of the title of Baron of Hoo and Hastynges, which lordship of Hoo is in the county of Bedford and the lordship of Hastynges is in the county of Sussex, and grant that he and his heirs enjoy all such rights as other barons of the realm."[53][54]

The Receiver-General's accounts for that year show a payment to him of one thousand livres tournois, as Chancellor of Normandy, for a journey which he made into England in November.[55]

In 1449, his term as Chancellor of the Duchy of Normandy concluded, and he returned to England, where he was regularly summoned to Parliament until the time of his death. In 1450 his friend and patron the Duke of Suffolk was killed by a hostile mob. Hoo himself faced a commission of inquiry in 1450–51 upon complaints that he had failed to pay the soldiery of France and Normandy under his authority.[56]

Legacy

The Lordship of Hoo and Hastings became extinct at the death of Lord Hoo, which occurred on 13 February 1454/5. He dated his will 12 February 33 Henry VI, making provision of £20 per annum for a chantry of two monks singing perpetually for himself and his ancestors at the altar of St Benignus (a Burgundian saint) at Battle Abbey.

The reversion of his manors of Wartling, Bucksteep (in Warbleton) and Broksmele (Burwash) was held by his stepmother Lady Lewkenor for life, but his feoffees were to make up a parcel of lands worth £20 a year for his brother Thomas Hoo (1416–1486), and the overplus, after the deduction of his funeral and testamentary charges, was to revert to his widow Dame Eleanor for life. Lord Hoo looked to her father Lord Welles to make an estate of lands and manors worth £100 per annum for Dame Eleanor: or, if he refused, brother Thomas was to sue Lord Welles by Statute Staple for £1000.[57]

The Rape of Hastings was to be sold, his brother having first refusal to buy it. From the proceeds the daughters of his second marriage, Anne,[58] Elizabeth and Alianor, were to have 1000 marks for their marriage portions in equal shares if they were ruled in their choice of spouse by Dame Eleanor and brother Thomas, whom he appointed his executors. Various annuities were made out of his manors of Offley (Hertfordshire), Mulberton (Norfolk) and Hoo (Bedfordshire).[59]

Dame Eleanor and brother Thomas renounced administration, which was granted instead to Richard Lewknor in December 1455.[60] Lewknor complained that Sir John Pelham's feoffees for the Rape of Hastings, Sir John Wenlock (of Someries, adjacent to Luton Hoo), Sir Thomas Tuddenham, Thomas Hoo 'squier' and John Haydon, were refusing to sell it and so impeding the performance of the will.[61] Thomas Hoo objected that he had attempted to purchase the Rape of Hastings (as appointed in the will) for £1,400 but was unable to obtain a sure estate in it, but had himself freely paid the marriage portions of Lord Hoo's three daughters.[62] By inquests held in 1455[63] and 1458[64] it was found that the Rape of Hastings was held not of the Crown but of the gift of Sir John Pelham, and in 1461 it was sold by the feoffees to William, Lord Hastings,[65] and was confirmed to him by patent of 1462.[66]

Tomb

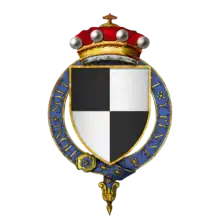

The brothers Thomas Hoo, Baron Hoo and Hastings (c. 1396–13 Feb 1455) and his half-brother Thomas Hoo are believed to be represented by the two recumbent effigies now on the Dacre Tomb at All Saints Church, Herstmonceux, Sussex.[67] In its final form the tomb ostensibly commemorated Thomas Fiennes, 8th Baron Dacre (d. 1534) and his son Sir Thomas Fiennes (d. 1528), but the figures themselves were apparently brought from Battle Abbey (?following its sale in 1539), where they had formed part of an older monument to the brothers Hoo.[68] During the restoration of the monument this was confirmed by underlying evidence of the heraldry of the tabards, and by the presence of a knightly Garter (mostly removed) appropriate to Lord Hoo but not to these Fiennes. The evidence for this are expertly described by the restorer.[69] The heraldry of the Hoo family and its antecedents is understood from surviving seals and from manuscript sources formerly in the custody of Sir Francis Carew of Beddington, Surrey and of Jonathan Keate, Bart.[70][71]

The heraldry worn by the figures of the tomb was interpreted lastly by Wilfrid Scott-Giles, Fitzalan Pursuivant Extraordinary. The tabard of Lord Hoo and Hastings shows quarterly sable and argent (for Hoo), quartered with azure, a fess between six cross-crosslets or (for St Omer), with, on an escutcheon of pretence, azure, fretty argent, a chief gules (for St Ledger). (This is the same as in the patron image in the "Hours of Lord Hoo".)

The tabard of the younger Thomas Hoo shows the arms of Hoo quartered with a bearing depicting a lion rampant, with a chief, with the arms of St Omer on the escutcheon of pretence. This lion was formerly taken to be the arms of Welles (or a lion rampant double queued sable):[72] which, however, if so, should have lions with two tails, and would allude to the marriage of the elder brother, not relevant to the younger Thomas Hoo.

The learned Herald suggests instead, that Lord Hoo may have quartered his arms with those of an extinct family of Hastange or Hastings (azure, a chief gules, over all a lion rampant or) when becoming Lord Hoo and Hastings, and that this coat, with an escutcheon of pretence for St Omer, was depicted for the younger Thomas Hoo on this monument to denote his association with the Lordship of Hastings. The monument has been repainted to represent this interpretation.[73]

However, this problem is older than the riddle of the tomb figures. The lion rampant, with a single tail but without the chief, is quartered with Hoo, with escutcheon of pretence for St Omer, in the original seal of Thomas Hoo the younger attached to his feoffment of 1481, and also recorded as having been appended to his own testification of his pedigree.[74] In the same way, the armorial roll seen by Sir Henry Chauncy before 1700, which had descended in the Carew family, concluded in its third membrane with the arms of Hoo impaled with Welles, "but" (wrote Sir Henry), "the Coat is mistaken, for the Lyon should be with a double Tayl".[75]

A canopied tomb at Horsham is also claimed to represent a member of the Hoo family.

Marriages and issue

Thomas Hoo married (1st) before 1 July 1428, Elizabeth Wychingham, daughter of Nicholas Wychingham, esquire, of Witchingham, Norfolk, by whom he had a daughter:

- Anne Hoo (born c.1424), who married Sir Geoffrey Boleyn, mercer and Lord Mayor of London:[76] they were the great-grandparents of Anne Boleyn.[77][78]

He married (2nd) before 1445 Eleanor Welles (daughter of Lionel de Welles, 6th Baron Welles and his first wife, Joan Waterton), by whom he had three daughters.[79] The first marriage of each was arranged and approved by their mother Eleanor and uncle Thomas.[80]

- Anne Hoo the younger (born c.1447). Owing to a misreading of Hoo's testament (which survives as incomplete extracts in manuscript at the College of Arms[81]), she is mistaken by some authors (following Thomas Fuller,[82] Sir William Dugdale[83] and Sir Henry Chauncy[84]) for a legatee called Jane or Joan, who receives £20 towards her marriage. However, original sources consistently show the three daughters of Eleanor as Anne, Alianore and Elizabeth, and show that they shared equally in the intended marriage portions.[85] Anne married:

- (1) Roger Copley, Esquire (died 1482[86]/1488), Citizen and mercer of London, of Roughey (Roffey) in Horsham, Sussex,[87] by whom she had three sons and six daughters;[88]

- (2) William Greystoke, Gentleman (living 1498), of London and St. Olave, Southwark, Surrey,[89] and

- ?(3) Sir Thomas Fiennes.[90][91]

- Eleanor Hoo, who married

- (1) Thomas Echingham, son and heir of Sir Thomas Echingham,[92] and

- (2) Sir James Carew of Beddington, Surrey.[93]

- Elizabeth Hoo, who married

After the death of Lord Hoo, his widow Eleanor remarried Sir James Laurence[96] (eldest son and heir of Sir Robert Laurence, fourth Squire of Ashton Hall in Lancashire, and perhaps his second wife Agnes Croft), by whom she had two further daughters and three sons. After his death in 1490, she is reputed to have made a third marriage to Hugh Hastings. She died before 1504.[97]

References

- G.E. Cokayne (ed.), The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, extant, extinct, or dormant, 2nd edition (London 1926), VI, pp. 561-67 (Family search viewer - registration required) (site accessed 10 May 2023).

- D. Richardson, ed. K.G. Everingham, Magna Carta Ancestry, 2nd Edn (2011), I, p. 498 (Ufford).

- 'Inquisitions post mortem: Richard II, File 14, nos. 339-343 – Thomas de Felton', in M.C.B. Dawes, A.C. Wood and D.H. Gifford, Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem: Volume 15, Richard II (HMSO, London 1970), pp. 134-49 (British History Online).

- H. Chauncy, The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire (B. Griffin, S. Keble, D. Browne, D. Midwinter and T. Leigh, London 1700), 'The Mannor of Hoo', pp. 510-11 (Google), in confusion accords a Felton marriage to both Sir Thomases, father and son: Blomefield (1769), thus misled, misses out a generation between Sir William Hoo and Lord Hoo and Hastings, making the two Sir Thomases into one person, and making Baron Hoo first to marry his own mother. The mistake goes back to Dugdale's Baronage.

- That Elizabeth Echyngham was the second wife of Sir Thomas Hoo the father (who died 1420), see D. Richardson ed. K. Everingham, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2nd Edition (2011), III, p. 18 item 9; Thomas the younger son is named explicitly in various sources as the brother of Sir Thomas Baron Hoo, e.g. in the 1445 concord with Lionel Welles, cf. Feet of Fines, CP 25/1/293/71, no. 308. View original at AALT; at which time his mother Elizabeth was still living.

- The relationship is shown thus in the Hoo pedigree given by G. Elliott, 'A monumental palimpsest: the Dacre tomb in Herstmonceux church', Sussex Archaeological Collections 148 (2010), at p. 141. (Read at thekeep.info pdf). By a typographer's error, Elizabeth's surname "Etchingham" is mistakenly printed beneath the name of Sir Thomas de Hoo (died 1420).

- Cooper, 'The families of Braose and Hoo', at pp. 109-10 (Internet Archive), citing Sussex retinue, Pipe Series, Carlton House Ride MSS.

- D. Richardson ed. K. Everingham, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2nd Edition (2011), III, p. 18 item 9. (Lewknor).

- 'Parishes: Offley', in W. Page (ed.), A History of the County of Hertford, Vol. 3 (VCH, London 1912), pp. 39-44 (British History Online).

- 'Luton' (manors of Luton Hoo and Stopsley), in W. Page (ed.), A History of the County of Bedford, Vol. 2 (V.C.H., London 1908), pp. 348-75 (British History Online).

- 'Parishes: Knebworth', in W. Page (ed.), A History of the County of Hertford, Vol. 3 (V.C.H., London 1912), pp. 111-18 (British History Online).

- Calendar of the Charter Rolls II: 1257–1300 (HMSO, London 1906), 20 Edward I, m. 5 no. 3, p. 421 (Internet Archive).

- Illingworth and J. Caley (eds), Placita de Quo Warranto temporibus Edw. I, II & III (Commissioners, Westminster 1818), p. 103 (Hathi Trust), Rot. 29.

- 'Margaret, daughter and heir of Ralph de Goushull', Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem, VIII: 1336–1347 (HMSO 1913), p. 511: Addenda to vol. V, no 692 (Internet Archive).

- Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem, III: 1291–1300 (HMSO 1912), pp. 135-38 no. 209-210 (Internet Archive). 'Lands of Peter de Goushill and of Ralph his son', in W. Brown (ed.), Yorkshire Inquisitions of the Reigns of Henry III and Edward I, III, Yorkshire Archaeological Society Records XXXI (1902), pp. 49-50 (Internet Archive).

- 'Parishes: Offley', W. Page (ed.), A History of the County of Hertford, Vol. 3, ed. William Page (London, 1912), pp. 39-44 (British History Online).

- A. Goodman, 'Sir Thomas Hoo and the Parliament of 1376', Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research XLI (1968), pp. 139-49 (open pdf available at oxfordacademic).

- Sir Thomas, who lived down to c. 1380, and his son William received letters of protection to serve beyond the sea with the Prince of Wales in autumn 1359, see C.P. Cooper (ed.), Chronological Catalogue of the Materials Transcribed for a New Edition of Rymer's Foedera (Commissioners/Record Office, 1869), pp. 47-48 (Google).

- Petition, Norwich 1365, in Liber Introit Civium, Lib.I, fol. 13; translation printed in J. Kirkpatrick, History of the Religious Orders and Communities, and of the Hospitals and Castles of Norwich (Edwards and Hughes, London 1845), pp. 14-16 (Internet Archive).

- Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem: '420: Nicholas Malemayns', Vol. IX: 1347–1352 (HMSO 1916), pp. 318-19; '79: Thomas de Sancto Omero', Vol. XII: Edward III, 1365–1370 (HMSO 1938), pp. 58-59 (Internet Archive).

- For this branch of Malmaynes see 'Parishes: Pagham, Manor of Aldwick' in L.F. Salzman (ed.), A History of the County of Sussex, Vol. IV: The Rape of Chichester (V.C.H., London 1953), pp. 227-33 (British History Online). This account avoids unsupported inferences found elsewhere.

- W.D. Cooper, 'The families of Braose of Chesworth, and Hoo', Sussex Archaeological Collections VIII (London 1856), pp. 97-131, pedigree at pp. 130-31 (Internet Archive). The earlier parts of this pedigree are fictitious: see H. Hall, 'Pedigree of Hoo', Sussex Archaeological Collections XLV (1902), pp. 186-97 (Internet Archive).

- Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III, A.D. 1333–1337 (HMSO 1898), p. 523 (Internet Archive); Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, III: 1334–1338 (HMSO 1895), p. 247 (Hathi Trust).

- '336. Inquisition to find the ages of Elizabeth and Alice, daughters of Thomas de Sancto Omero, two of the heirs of Nicholas de Malemayns', Calendar of Inquisitions post mortem X: 1352–1361 (HMSO 1921), pp. 289-90 (Hathi Trust).

- British Library, Yates Thompson MS 14 (British Library Digitised Manuscripts): View at British Library MS Viewer.

- F. Blomefield, ed. C. Parkin, An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk, Revised edition, Vol. VII (William Miller, London 1807), pp. 456-57 (Internet Archive).

- Her will is dated 1375, proved in Archdeaconry Court of Norwich, Haydone Register, fol. 5.

- See 'Stained glass of St Mary Magdalen church, Mulbarton, Norfolk, at Norfolk Stained Glass website.

- F. Blomefield, ed. C. Parkin, An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk, Revised edition, Vol. V (William Miller, London 1806), at pp. 75-79; VII (1807), pp. 219-20, and pp. 456-57 (Hathi Trust).

- H. Nicolas, Proceedings and ordinances of the Privy Council of England, Vol. I: 10 Richard II to 11 Henry IV (Commissioners, Westminster 1834), p. 183 (Google).

- For the Wychingham family, see 'Wychingham's manor, Witchingham' in F. Blomefield, ed. C. Parkin, An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk, Revised edition, Vol. VIII (William Miller, London 1808), at pp. 298-300 (Hathi Trust). Blomefield does not mention the Hoo-Wychyngham marriage here, but does so at Vol. V, p. 77.

- N.H. Nicolas, Testamenta Vetusta, 2 vols (Nichols and Son, London 1826), I, pp. 207-11 (Google).

- Browne Willis, The History and Antiquities of the Town, Hundred, and Deanry of Buckingham (Author, London 1755), p. 11 (Internet Archive).

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', pp. 110-12 (Internet Archive), citing British Library, Cottonian charters, xxix, 32.

- The XIIIJ year of King Henry VI', Hall's Chronicle: Containing the History of England, during the Reign of Henry the Fourth (etc). (J. Johnson et al., London 1809), p. 179 (Internet Archive). T. Carte, A General History of England, II (Author, London 1750), Book XII, pp. 712-13 (Hathi Trust).

- F. Du-Chesne, Histoire des Chanceliers et Gardes des Sceaux de France (L'Autheur, avec privilege du Roy, Paris 1680), pp. 448-49 (BnF Gallica).

- G.E. Cokayne, Complete Peerage, vol. VI, p. 562

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', pp. 112-15, citing British Museum, Additional Charters nos. 445, 1189, 581, 1203, 463 and 467.

- T. Rymer, ed. G. Holmes, Foedera, Conventiones, Literae et cujuscunque Acta Publica (3rd edition) Vol. V Part 1 (John Neaulme, Hagae Comitis 1741), p. 115 (Internet Archive).

- Rymer, Foedera, Vol. V Part 1, pp. 133-36 (Internet Archive); Carte, General History of England, II, Book XII, p. 724 (Hathi Trust).

- See also T. Rymer, Foedera Vol. XI (Apud Joannem Neulme, London 1739–1745), pp. 57-67 and pp. 88-108 (British History Online). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Henry VI, IV: 1441–1447 (HMSO 1937), p. 232-34 (Hathi Trust).

- J. Anstis 'A Supplement to Mr Ashmole's History touching Garter King of Arms', The Register of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, 2 Vols (John Barber, London 1724), I (Introductory volume), pp. 338-39 (Hathi Trust).

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', pp. 115-16, with references there cited.

- The National Archives (UK), C 139/156/11: recited in Cooper, 'Families of de Braose and Hoo', at pp. 118-19 (Internet Archive).

- Feet of Fines, CP 25/1/293/71, no. 308. View original at AALT.

- L.L. Williams, 'A Rouen Book of Hours of the Sarum Use, c. 1444, belonging to Thomas, Lord Hoo, Chancellor of Normandy and France', Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol. LXXV (1975), pp. 189-212 (Jstor – Sign-in required).

- Royal Irish Academy MS 12 R 31. The "Hours of Lord Hoo" were presented to the Royal Irish Academy in 1874: an inscription records that it may once have belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots.

- Calendar of the Close Rolls, Henry VI, IV: 1441–1447 (HMSO 1937), p. 172 (Hathi Trust).

- Many writers give the date 1439, but the patents show 1445.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry VI Vol. IV: 1441–1446 (HMSO 1908), p. 350 (Internet Archive).

- J. Anstis, The Register of the Most Noble Order of the Garter 2 Vols (John Barber, London 1724), I (Introductory volume), p. 38; II (Text volume), pp. 129-31, and see note "n" at p. 145 (Hathi Trust, which reverses the volume numeration).

- E. Venables, 'The Castle of Herstmonceux and its lords', Sussex Archaeological Collections IV, (1851), pp. 125-202, at pp. 150-52 (Internet Archive).

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry VI, Vol. V: 1446–1452 (HMSO 1909), p. 165 (Hathi Trust).

- The Latin text of the Patent is transcribed in full in Report on the Dignity of a Peer of the Realm, Vol. V: Fifth Report, and Appendix (Commissioners, Westminster 1829), p. 266 (Google).

- British Library, Receiver-General's Accounts for Normandy, 1448–1449, Additional MS 11509, see original in Digital viewer (British Library).

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry VI, Vol. V: 1446–1452, pp. 435, 439, 444 (Hathi Trust).

- 'The Testament of the Lord Hoo', in Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', pp. 119-21 (Internet Archive).

- This refers to the second Anne, the elder Anne being already married to Sir Geoffrey Boleyn who died in 1463. A bequest of £20 to the marriage of "Johan" does not refer to any of these daughters. Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', p. 120 note 89, traces this mis-identification to Sir W. Dugdale (see below).

- Cooper's transcript is more complete than 'Abstract of Will of Thomas Lord Hoo and Hastings', in N.H. Nicolas, Testamenta Vetusta (Nichols & Son, London 1826), I, pp. 272-74.

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', p. 121 (Internet Archive).

- The National Archives (UK), Early Chancery Proceedings, C 1/26/118. View original at AALT.

- The National Archives (UK), Early Chancery Proceedings, C 1/44/187. View original at AALT.

- The National Archives (UK), Inquisitions post mortem: Hoo, Thomas, kt. (1454–1455), C 139/156/11.

- Carlton House, Ride MSS.

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', p. 122 (Internet Archive)

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward IV, Vol. I: 1461–1467 (HMSO 1897), pp. 137-38 (Hathi Trust).

- Image at Geograph.org.uk. Another at flickr by poundhopper1.

- J.E. Ray, 'The parish church of All Saints, Herstmonceux, and the Dacre tomb', Sussex Archaeological Collections LVIII (1916), pp. 21-64, at pp. 36-55 (Internet Archive).

- G. Elliott, 'A monumental palimpsest: the Dacre tomb in Herstmonceux church', Sussex Archaeological Collections 148 (2010), pp 129-44. (Read at thekeep.info pdf).

- cf. Harleian MS 381, item 41, at Catalogus Librorum MSS Bibliothecae Harlaianae I, p. 229b (Internet Archive). Described by Chauncy, Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, p. 511. Chauncy's identification of the marriages of Lord Hoo's parents and grandparents is correct, but the punctuation of his original edition, in describing the different coats in the Keate MS, may have given rise to confusion. It is more clearly printed in the 1826 edition, Vol. II, pp. 405-06 (Google).

- Two seals are engraved in Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo': others are shown in the Medieval Genealogy website, including a charter of 1366 with seals of Sir William de Hoo and Dame Alicia (St Omer) de Hoo , and a grant of 1372 Huntington Library, San Marino BA v.48/1464 with seals of Sir Thomas de Hoo and Isabella (St Leger) de Hoo.

- Ray, 'The parish church of All Saints, Herstmonceux, and the Dacre tomb', pp. 36-55. See Chauncy, Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, p. 511.

- Elliott, 'A monumental palimpsest', p. 139.

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', pp. 126-27 (Internet Archive).

- Chauncy, Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, pp. 404-06 (Google).

- A.B. Beavan, The Aldermen of the City of London Temp. Henry III to 1912 (Corporation of the City of London, 1913), II, p. 10.

- J. Hughes, 'Boleyn, Thomas, earl of Wiltshire and earl of Ormond (1476/7–1539), courtier and nobleman', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2007). E.W. Ives, 'Anne (Anne Boleyn) (c.1500–1536), queen of England, second consort of Henry VIII', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography' (2004).

- Richardson IV 2011, pp. 305–11.

- D. Richardson, ed. K.G. Everingham, Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, 2nd edn., 4 vols (Salt Lake City, 2011), IV, at pp. 310 (Google).

- So stated by Thomas Hoo in his Answer to the Bill of James Carrue and Eleanor, The National Archives, Early Chancery Proceedings C 1/44/186 item 2. View original at AALT. Hoo specifies that the elder Eleanor is the mother to the three daughters Eleanor Echingham, Anne Copley and Elizabeth Massyngberd.

- Cooper, 'Families of Braose and Hoo', p. 119 note 83 (Internet Archive), citing College of Arms MS J. vij. fol. 61.

- T. Fuller, The History of the Worthies of England (Thomas Williams, London 1662), 'Bedfordshire: Memorable persons: Sheriffs of Bedford and Buckinghamshire: Henry VI', p. 124 (Umich/eebo).

- W. Dugdale, The Baronage of England (Abel Roper, John Martin and Henry Herringman, London 1675–1676), 'Lord Hoo and Hasting' at pp. 233-34 (Umich/eebo). Dugdale's article, a bold attempt, contains various confusions. Fuller and Dugdale list the same husbands for the daughters, suggesting the shared origin of the mistake.

- Chauncy, The Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, pp. 510-11 (Google).

- The names of the two Annes, Eleanor and Elizabeth are plainly recited with their husbands' names in Boleyn v Hoo, The National Archives, Early Chancery Proceedings, C 1/2/82-85. Full transcripts in J.W. Bayley (ed.), Calenders to the Proceedings in Chancery during the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, to which are prefixed examples of earlier proceedings in that court, Vol. II (Commissioners, Westminster, 1830), 'King Edward IV': pp. li-liii (Google). View originals at AALT. See also the suit Boleyn v Echyngham in De Banco rolls, CP 40/829 (Michaelmas 8 Edward IV), m. 606 front and dorse; originals at AALT, m. 606 front a and b, and 606 dorse.

- He declared his last will on 16 May 1482: The National Archive, ref. C 131/99/8.

- This Roger Copley appears in Mercers' Court records in 1461–63, 1466 and 1489, his name spelt "Couple" or "Cople", see L. Lyell and F.D. Watney (eds), Acts of Court of the Mercers' Company 1453–1527 (Cambridge University Press 1936), pp. 49-59, 191, 281.

- A Pedigree of Hoo and Copley was attempted by E. Cartwright, The Parochial History of the Rape of Bramber in the Western Division of the County of Sussex, Vol. II Part 2 (J.B. Nichols and Son, London 1830), pp. 339-40 (Google). It contains some inaccuracies.

- See Graystok v Goldesburgh, The National Archives, Early Chancery Proceedings C 1/137/14, Summary at Discovery.

- Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry (2011), IV, pp. 310-11. (Welles)

- The Fiennes marriage is said to be evidenced in T.N.A. Early Chancery Proceedings, Fenys v Fayrefax, C 1/254/16 Summary at Discovery.

- Chauncy, Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, p. 510.

- N. Nicolas, Testamenta Vetusta, I, p. 272, note. See The National Archives, Early Chancery Proceedings, C 1/44/186-188, for both husbands.

- Richardson IV 2011, p. 311.

- Chauncy, Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire, p. 511, for both husbands.

- The National Archives (UK), Discovery Catalogue, ref. C 1/41/239 (1467–72).

- Richardson, Magna Carta Ancestry (2011), IV, p. 310.

Sources

- Cokayne, George Edward (1949). The Complete Peerage, edited by Geoffrey H. White. Vol. XI. London: St. Catherine Press. p. 51.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1945). The Complete Peerage, edited by H.A. Doubleday. Vol. X. London: St. Catherine Press. pp. 137–142.

- Richardson, Douglas (2004). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company Inc. pp. 179–180.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. pp. 320–1. ISBN 978-1-4609-9270-8. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)