Thorntoun house and estate

Thorntoun School was opened by Barnardo's in September 1971 for children with emotional difficulties aged 11 to 16 years. The school closed in 1990 and Thorntoun is now a nursing home. The complex lies between the villages of Springside (North Ayrshire) and Crosshouse, Kilmarnock in East Ayrshire, Scotland. The old Thorntoun mansion house was demolished in the late 1960s, leaving the West Lodge, some of the home farm outbuildings, the stables and the walled garden as 'memorials' to the ancient history of the site. Many fine trees remain from the estate policies and the surviving gardens are very well maintained (2007). An entrance with a slight deviation from the old course has been created to serve the large modern buildings which house the nursing home.

The History of Thorntoun house and estate

In 1823 the historian Robertson[1] describes "Thornton" as being "situated about half way betwixt Irvine and Kilmarnock: the manor or place (palace) is an elegant modern mansion, set down on the brow of a considerable height, overlooking, from amid its fine old timber and more recent plantings, a great expanse of rich country."

In 1866 James Paterson, another historian, brought up locally, gives 'Thorntoun' as "This property, situated to the west of Busbie (Knockentiber), is about 300 acres (1.2 km2) in extent. It belonged, of old, according to Wood, to one of the branches of the Montgomerie family."[2]

The Montgomerie, Mure and Ross families

| Etymology |

| Near Thorntoun in 1604[3] was a Thornhill. This fact, combined with the consistent spelling over the years suggests that the name relates to 'Thorns' i.e., either Blackthorn (Sloe) or Hawthorn. Both species are still common in the area today. A 'Toun' or 'Ton' was a farm and its outbuildings, originally an area fenced or walled off, with a dwelling within.[4] |

Thorntoun was at first part of the Barony of Kilmaurs and then later it was placed within the Barony of Robertoun, Parish of Kilmaurs. The estate is first recorded as belonging to Murthhaw or Murchaw de Montgomery, who is mentioned in the Ragman Rolls (a list of those loyal to Edward I of England) of 1296. A Johne of Montgomery of Thornetoun is mentioned in a legal document of 1482, forfeiting the estate to Lord Home by order of King James V. By the beginning of the seventeenth century Thorntoun had passed into the ownership of another ancient and renowned Ayrshire family, the Mures (or Muirs), a branch of the Mures of Rowallan Castle near Kilmaurs. James Mure, Burgess of Glasgow, had married Margaret, a daughter of Robert Ross of Thorntoun on 27 June 1607 and inherited the property through his spouse. Nothing is known of how and when the Ross's, another ancient Ayrshire family, had come to possess Thorntoun. Hew (Hugh) was one son, a merchant in Edinburgh, his will is dated 4 Nov 1679 and another son, James succeeded to the property of Thorntoun, and married a Janet Naper, who died in 1626. Robert Muir, son of James & Janet, is mentioned in a document of 1634.[2]

The Cuninghame Family

Archibald Muir of Thorntoun was knighted by King William III in 1698 and his only daughter, Margaret, married John Cuninghame of Caddel, in the Parish of Ardrossan, in 1699. They inherited Thorntoun and Caddel and had two sons and three daughters. Archibald succeeded his father and John became a successful merchant in Lisbon (Portugal), eventually retiring to live at Carmelbank (previously called Mote), adjacent to Thorntoun. Their father was married a second time to a daughter of Mr. Stevenson of Montgreenan, by whom they had another sixteen children. This John Cuninghame died in 1753.

Archibald Cuninghame, who was a captain in Boscawen's 29th. Regiment of Foot, married Christiana, eldest daughter of Andrew Macredie of Perceton in 1754. They had three sons, John, Andrew and Archibald and five daughters. Their eldest son was Lieut-Col. John Cuninghame, born in 1756 and died in 1836. He entered the army in 1775 and served in America (now the USA) and the West Indies. He was severely wounded whilst fighting the French in the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. John recovered to serve on board the 74 gun, HMS Montague, at the great Caribbean naval victory of the Battle of the Saintes against the French who were commanded by Admiral Count François Joseph Paul de Grasse. He left the army as a lieutenant-colonel in 1802. John's spouse was Sarah Peebles, only daughter of Major John Peebles in Irvine, late of the 42nd regiment, She was born in 1783 and died in 1854. They had nine children, Andrew, John, Archibald, Anna, Christiana, Helen, Margaret, Catherine and Sarah. Many of the family died in childhood or when relatively young. Catherine married Clarence Esme Stuart of Oldenham Abbey, Hertfordshire. Christiana first inherited, followed by Sarah. The colonels' rental value of the property in 1799 was £300 (Scots) per annum, compared with that of the Earl of Eglinton, who had an income of £1,120 (Scots) from his estates.[5] The Lieut-Col and his family are commemorated and / or buried at the family burial plot in the cemetery of St Maurs-Glencairn kirk in Kilmaurs.[1]

The Wrey Family

Sarah Cuninghame's spouse was George Bourchier Wrey from North Devon. They had a son, George Edward Bourchier Wrey who had succeeded to the property by 1912. He appears to have inherited Carmelbank from his great-uncle, John Cuninghame by this date.[5] The combined rental income of Thorntoun and Carmelbank was £2,640 12s 0d., the second highest in the parish, only exceeded by Robert Morris Pollock-Morris of Craig house.[5] This is a reversal for both of the situation in 1799 and may reflect earnings from the establishment of collieries, etc. rather than the straightforward 'traditional' income from farms and the like.

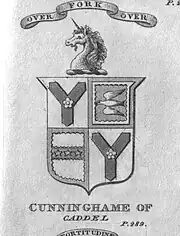

Coat of arms

The coat of arms is a shakefork with a cinquefoil, for Glengarnock: a cross moline within a bordure invected, for Caddel: three stars within a bordure invected, for Muir of Thorntoun; and a crest of a unicorn's head. The motto is "Over fork over" and as such is unchanged from that of the senior branch, the Cunninghames of Kilmaurs, Earls of Glencairn.[1]

The Barony of Robertoun

This barony, once part of the Barony of Kilmaurs, ran from Kilmaurs south to the river Irvine. It had no manor house and belonged to the Eglinton family latterly. The following properties were part of the barony: parts of Kilmaurs, Craig, Gatehead, Woodhills, Greenhill, Altonhill, Plann, Hayside, Thorntoun, Rash-hill Park, Milton, Windyedge, Fardelhill, Muirfields, Corsehouse and Knockentiber.

The Darien Affair

The Darien Company was an attempt by the Scots to set up a trading colony in America in the late 1690s, however the opposition from England and elsewhere was so great that the attempt failed with huge losses and great financial implications for the country and for individuals. Half of the whole circulating capital of Scotland was subscribed and mostly lost. In Cunninghame some examples of losses are Sir Archibald Mure of Thorntoun (£1000), Major James Cunninghame of Aiket (£200), Sir William Cunninghame of Cunninghamhead (£1000), William Watson of Tour (£150) and James Thomson of Hill in Kilmaurs (£100). In modern terms a thousand pounds loss in the 17th century must have been a devastating blow to the family finances.[6]

The journals of Major John Peebles

Located in the Cuninghame of Thorntoun Papers in the National Archives of Scotland is the American Revolution journal of Captain John Peebles (1739–1823), a grenadier officer of the 42nd (Royal Highland Regiment or Black Watch). The journal provides an enlightening insight into the life and activities of the British army during the rebellion. John Peebles was John Cuninghame's father-in-law.

In 1780 Captain John Peebles noted in his journal the "General Rules for Manouvring the Battn. by the Commanding Officer"; appended to these directions are a series of signals for giving orders to the troops.

Signals by drum

The following extracts illustrate the battlefield manoeuvres which drum 'signals' could signal.

Preparative, to begin firing by Companies, which is to go on as fast as each is loaded till the first part of the General when not a shot more is ever to be fired.

Grenadrs. March. to advance in Line.

Point of War. to Charge.

To Arms. to form the Battn. (whether advancing or Retreating in Column) upon the leading division.

Double flam. to halt Upon the word forward, in forming, the Divisions to run up in Order.

The New Jersey Brigade and the Monmouth Campaign

Here are a few extracts from John's American War of Independence journal:

Monday 22d. June rain in the night The Army... moved on to the Black Horse a small Village about 7 or 8 miles from Mount holly & Encampd in two lines facing NW—Genl. Kniphausens Division on the left—the Queens Rangers on our Right... Maxwells Corps of Rebels left the Black horse this Morng.

Sunday 28 June a fight...

[This was the Battle of Monmouth].

Monday 29th. June … Genl. Knyphausens Division moved on to Middletown, with the Provision & baggage Train - & wounded.

Evidence from Ordnance Survey (OS) and other maps

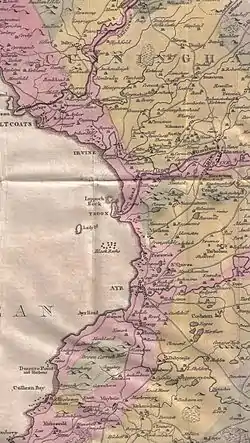

Timothy Pont's map of 1604 as published by Johan Blaeu in 1654 clearly marks Thorntoun[3] so do Ainslie's map of 1821,[7] Armstrong's map[8] of 1775 and Herman Moll's map of The Shire of Renfrew with Cuningham in 1745. General Roy's Military Survey map of Scotland (1745–55) shows the site named as simply 'Thorn'.

Thomson's map of 1828 gives some detail, showing two entrances and driveways, with substantial woodlands and an enclosed park on the Springside boundary, as used for deer or cattle. He also marks the name 'Mains', indicating the home farm, apparently situated to the right of the house on the 'east' driveway on the Crosshouse side.[9] This was later rebuilt above the 'West' Lodge (1898 OS), however buildings remain in the 'old' site up until the time of the 1921-28 OS map. This map also indicates a building roughly in the centre of the walled garden. The walls show no signs of typical conservatory-style greenhouses built against them, so this may be a large 'greenhouse'. The stone is red sandstone with freestone corners and coping stones. The materials were landed at Troon harbour and brought here by cart. A 'trig point' is carved on the corner of the walled garden nearest the old quarry.[10] A well is shown near the walled garden in the vicinity of the modern housing. An old freestone quarry is shown on the 1860 map, close to the trig point on the walled garden. Buildings are indicated on the 1912 OS map as lying fairy close to the northern wall of the walled gardens. Only vague foundations and scattered stones now exist at the site in 2007.

The 1912 map appears to show an enclosed area, partially wooded, in the nearby field, of a similar size and shape to the walled garden. This may be a fox covert or cover for pheasants. No sign of this feature is now extant (2007).

A small cottage used to stand near the entrance to the new driveway into the nursing home.[10] The 1912 map shows a track running into the estate at this point and this building may have served as a lodge house. The name 'West Lodge' itself suggests that a second lodge existed at one time and the 1911 OS clearly marks this lodge situated at what is now the realigned entrance to the main driveway.

A number of local names appear to have been lost, such as Thornhill (1604), Greenside, Hayside, and Laurieslaw from 1828 and Montgomery Holme (1745–1828). A Laurieland Row, Crawfurdhill and Thorntoun Row were present in 1860. A Thornyhill cottage is however present (2007) near Busbiehill.

The Royal Mail re-organised its postal districts in the 1930s and at that point many hamlets and localities ceased to exist officially, such as Sprighill, Corsehill, Bankhead and Kirklands.[11][12] The present Springside was called Bankhead up until at least the 1921 - 1928 OS, the hamlet of Springside being originally clustered around the railway station.

A number of Lime kilns are marked on 1860 OS, the nearest being at Holme and West Gatehead farms.

The turnpike and milestones

In 1776[13] Thorntoun is marked on the toll road to Irvine and the two milestones are shown.

A horse trough was present on the left of the main road facing Springside, in between the West Lodge and the lane up to Thorntoun Mains; the trough has long vanished, but its niche in the bank with its side walls is still there. This was a turnpike or toll road, with the nearest toll house located at Crosshouse. The 1860 OS map show two milestones were near Thorntoun, one close to the junction of the lane down to Hallbarns and Cauldhame farms and the other on the left facing Crosshouse, before the Holm Burn bridge, indicating 4 miles (6.4 km) to Irvine and three to Kilmarnock. Most milestones were buried during the Second World War so as not to provide assistance to invading troops, German spies, etc. This happened all over Scotland, however Fife at least was more fortunate than Ayrshire, for the stones were taken into storage and put back in place after the war had finished.[14]

The name 'turnpike' originated from the original 'gate' used being just a simple wooden bar attached at one end to a hinge on the supporting post. The hinge allowed it to 'open' or 'turn' This bar looked like the 'pike' used as a weapon in the army at that time and therefore we get 'turnpike'. The term was also used by the military for barriers set up on roads specifically to prevent the passage of horses. In addition to providing better surfaces and more direct routes, the turnpikes settled the confusion of the different lengths given to miles,[9] which varied from 4,854 to nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m). Long miles, short miles, Scotch or Scot's miles (5,928 ft), Irish miles (6,720 ft), etc. all existed. 5,280 feet (1,610 m) seems to have been an average! Another important point is that when these new toll roads were constructed the turnpike trusts went to a great deal of trouble to improve the route of the new road and these changes could be quite considerable as the old roads tended to go from farm to farm, hardly the shortest route. The tolls on roads were abolished in 1878 to be replaced by a road 'assessment', which was taken over by the county council in 1889.

Natural history

.JPG.webp)

The woodland policies contain a mixture of mature oak, Norway maple, beech, copper beech, willow, horse chestnut, aspen, rhododendron, Scots pine, alder, ash, elm, monkey puzzle, willow, sycamore, holy, elder, yew, lime, hawthorn, blackthorn and other species. The woodland floor has drifts of snowdrops, bluebells and some primroses, together with ground ivy, bird's-foot trefoil, coltsfoot, three-veined sandwort, vetch, ladys mantle, red campion, bistort, foxgloves, tuberous comfrey, ivy, yellow saxifrage, pendulous sedge, brambles, etc. An area of the woodland is a genuine 'bluebell wood.' The large leaved Persian Ivy (Hedera colchica)[15] grows at the walled garden, a relict of the exotic plantings of yesteryear, as is the very unusual stand of Butcher's Broom. The ground flora of the Thorntoun policies is typical of the semi-natural diversity of many deciduous woodlands in Ayrshire, particularly of those associated with current or previous country estates. The bird fauna is quite diverse, including pigeons, rooks, starlings, blackbirds, kestrels, etc. Hedgehogs are present (2007).

The Collieries and Coal Pits

The 1860, 1898–1904 and, 1911 and 1912 OS maps all show that the extent to which the Thorntoun House was surrounded by collieries, coal pits and freight only railway or 'tram' lines. Collieries were located near Cauldhame farm (Cauldhame and Springhill (Pit No.4), one at Crosshouse, one at Holme farm and at Bankhead (one called West Thorntoun), Springhill (Pit No.1) and Springhill (Pit No.2) at Sprighill, and another between Busbiehill and Warwickhill. These were all served by standard gauge mineral railway lines, criss-crossing the countryside; they all now lifted, with only a few embankments left to indicate their original course. The Thorntoun colliery beside Holme farm had a miner's row and a railway which ran over several wooden bridges down to join the surviving railway through Gatehead at Holm ley, close to the Laigh Milton viaduct. In 1860 numerous old and current coal pits dotted the area. The bing of Springhill (Pit No.3) still lies close to Springside in the field that may have been the Thorntoun deer park.

Miscellaneous and Trivia

Strawhorn [16] states in 1951 that a fair number of inhabitants are of Cornish extraction, having been brought up here to break a coal workers strike in the 1880s.

| Etymology |

| Carmel, the oldest form of which is Caremuall, is thought to be derived, according to McNaught,[5] from the Gaelic 'Car' meaning a 'fort', and 'Meall'. meaning a hill. Therefore, 'The fort on the hill'. |

The road running down to Springside is known as the 'Thorntoun Brae' and on the left, just before Thorntoun bridge over the Garrier Burn was the local curling pond, clearly marked on the 1911 OS map[12]

A mill-wand was the rounded piece of wood acting as an axle with which several people would role a millstone form the quarry to the mill and to permit this the width of some early roads was set at a 'mill-wand breadth'. The nearest mills to Thorntoun were those at Busbie beside Crosshouse and Laigh Milton mill, where the building, weir and part of the wheel still exist (2007).

Margaret Muir, was the spouse of Frederick Cunninghame, a merchant in Kilmarnock. She died on 17 March 1685 and could therefore have been a daughter of James Mure and Janet Naper.

One of the bells in St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh is inscribed "Archibald Mure, Thorntoun, Lord Provost"

In 1902 a Mrs. Margaret Sturrock, née Finnie was living at Thorntoun House.[17]

A Trig point at the walled garden marks a height of 169 feet (52 m) elevation above sea level.

Letters survive in the National Archives of Scotland concerning the imprisonment of Margaret Cuninghame at Lucca in Tuscany, Italy for evangelical teaching, 1853-1854.

The Cuninghames of Thorntoun & Caddel held title to lands in Ayr and tenements in Glasgow, 1573–1836, including, tacks of lands in Stirling.

The estate factors' accounts of Caddell and Thorntoun, survive for the period 1700-1947. Thorntoun house may have been demolished in 1947.

Sir Philip Bourchier Sherard Wrey stood for election to the Southern Rhodesia legislative council in 1920.

Mr Cunningham attended the famous 1839 Eglinton Tournament in what is now Eglinton Country Park and he was allotted a seat in the Grand Stand.[18]

Views in and around Thorntoun - Spring 2007

Inside the old walled garden.

Inside the old walled garden. Outside the old walled garden.

Outside the old walled garden. The 'Thorntoun Sign' made by pupils from the old Dr. Barnardo's school.

The 'Thorntoun Sign' made by pupils from the old Dr. Barnardo's school. The new driveway up to the nursing home.

The new driveway up to the nursing home. The Thorntoun woodlands from near Busbiehill at the 1860s mineral railway crossing.

The Thorntoun woodlands from near Busbiehill at the 1860s mineral railway crossing. The Thorntoun woodlands from near Kirkland farm, Springside.

The Thorntoun woodlands from near Kirkland farm, Springside. The Thorntoun woodlands from near Kirkland farm, Springside.

The Thorntoun woodlands from near Kirkland farm, Springside. Thorntoun Brae and bridge viewed from Springside.

Thorntoun Brae and bridge viewed from Springside.

See also

References

- Robertson, George (1823). A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire. Pub. A. Constable, Irvine.

- Paterson, James (1866). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V.III. – Cunninghame. Pub. J. Stillie. Edinburgh.

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- Warrack, Alexander (1982)."Chambers Scots Dictionary". Chambers. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- McNaught, *McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Parish and Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner.

- Dobie, James (1876). Pont's Cunninghame topographized 1604-1608 with continuations and illustrative notices (1876). Pub. John Tweed.

- Ainslie, John (1821). A Map of the Southern Part of Scotland.

- Armstrong and Son. Engraved by S.Pyle (1775). A New Map of Ayr Shire comprehending Kyle, Cunningham and Carrick.

- Thomson, John (1828). A Map of the Northern Part of Ayrshire.

- Thompson, George, Head Gardener. Thorntoun Nursing Home. 2007. Oral Communication to Griffith, Roger S. Ll.

- Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire. Pub. Edinburgh.

- Springside's Auld Lang Syne (2002). Springside Women's Health Group. P. 2.

- Taylor, G. and Skinner, A. (1776) 'Survey and maps of the roads of North Britain or Scotland'

- Stephen, Walter M. (1967-68). Milestones and Wayside Markers in Fife. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, V.100. P. 184.

- Hessayon, D. G. (1983). The Tree and Shrub Expert. pbi Publications. ISBN 0-903505-17-7. P. 76

- Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire. Pub. P. 475

- Springside's Auld Lang Syne (2002). Springside History Group. P. 13.

- Aikman, J & Gordon, W. (1839) An Account of the Tournament at Eglinton. Pub. Hugh Paton, Carver & Gilder. Edinburgh. M.DCCC.XXXIX. P. 8.