Pier Head

The Pier Head (properly, George's Pier Head[1][2]) is a riverside location in the city centre of Liverpool, England. It was part of the former Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City UNESCO World Heritage Site, which was inscribed in 2004, but revoked in 2021.[3][4] As well as a collection of landmark buildings, recreational open space, and a number of memorials, the Pier Head was (and for some traffic still is) the landing site for passenger ships travelling to and from the city.

History

By the 1890s, the George's Dock, where the Pier Head now is, was essentially redundant. Built in 1771, it was the third dock built in Liverpool, and was too small and too shallow in depth for the commercial ships of the late 19th century.[5] Most of the site was owned by the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board, set up by Parliament in 1857; a small part of the site still was still held by the Corporation of the City of Liverpool.[5] The board and the corporation had differing priorities, and the former were not inclined to forgo any commercial advantage for the benefit of the latter.[5]

In January 1896, the two bodies began discussions, with the corporation's team headed by Frederick, Lord Derby (who was then the city's Lord Mayor), and the Board's representatives led by Robert Gladstone, a member of the Liverpool family of which W.E. Gladstone was the best-known.[5] The Corporation sought to persuade the Board to accept its offer to buy the site, reserving a portion of it for new Board offices. After two years of negotiation this was agreed, and Parliamentary authority was obtained for the deal. The Corporation paid £277,399 for the site, from which the Board reserved about 13,500 square yards for its own building.[5]

The board pressed ahead with its new headquarters, and announced a competition, restricted to local architects, to be adjudicated by Alfred Waterhouse.[5] Despite some protests in national architectural journals about the exclusion of architects from beyond Liverpool, the local firm of Briggs, Wolstenholme, Hobbs and Thornley was appointed. A neo-baroque design was approved, with a central dome added at the last minute before the final plans were adopted in time for the start of building work in March 1903.[5] The building was opened in the summer of 1907.[5]

When it acquired the site, the corporation had been confident of finding tenants for the two remaining plots suitable for large-scale buildings, but no such prospective tenants came forward, and it was decided to offer the freehold of the sites for sale. However, at an auction of the sites in 1905 there were no bidders. The following year, the Royal Liver Friendly Society made an approach through Walter Aubrey Thomas, a local architect, successfully offering considerably less for a site than the corporation had hoped for: £70,000 instead of £95,000.[5] Gladstone and the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board expressed consternation at the height of the Royal Liver Society's proposed new headquarters, sometimes described as "England's first skyscraper",[5] but after much debate the corporation approved the plans.[5]

The last of the three Pier Head sites between the Liver Building and the Docks and Harbour Board offices was for some time intended to be developed on behalf of the corporation, partly to replace a nearby public baths and partly as offices for the city's new tram network.[5] This scheme fell through, and in the early years of the 20th century a combined public baths and customs house was proposed. After several years that scheme, too, came to nothing, and in 1913 the Cunard shipping line announced its intention to build a new headquarters in Liverpool. The Cunard Building was built of reinforced concrete, clad in Portland Stone, in a style intended to recall grand Italian palaces, described by the architectural historian Peter De Figueiredo as "a match for its more ostentatious neighbours in expressive power but greatly superior in refinement of detail and proportion."[5]

In 2002, the Pier Head, and the adjacent Mann Island, were subjected to an ill-fated development scheme known as the "Fourth Grace" project. This, with the winning entry, designed by Will Alsop and known as "the Cloud", was abandoned in 2004 after "fundamental changes" to the original waterfront plan left it unworkable.[6]

In 2007, work began on a new scheme, to re-house the Museum of Liverpool Life. The new museum, known as the Museum of Liverpool opened in 2011.[7] Work also started in 2007 to build a canal link between the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the South Docks. The £22 million pound, 1.6-mile extension to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was officially opened on 25 March 2009 and opened to boaters at the end of April 2009. It links the 127 mi (204 km) of the existing canal to the city's South Docks, passing the Pier Head and its landmark buildings.

Landmark buildings

The site encompasses a trio of landmarks, built on the site of the former George's Dock and referred to since at least 1998[8] as "The Three Graces":

- Royal Liver Building, built between 1908 and 1911 and designed by Walter Aubrey Thomas. It is a grade I listed building consisting of two clock towers, both crowned by mythical Liver Birds. The building is the headquarters of the Royal Liver Friendly Society.

- Cunard Building, constructed between 1914 and 1916 and a grade II* listed building. It is the former headquarters of the Cunard Line shipping company.

- Port of Liverpool Building, built from 1903 to 1907 and also grade II* listed. It is the former home of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board.

Also on the site is the Grade II listed George's Dock Building, to the east of the Port of Liverpool building. It was built in the 1930s and contains offices and ventilator equipment for the Queensway Tunnel.

Landing stages

Trans-Atlantic shipping

Cunard Line, 1875

Cunard Line, 1875 Dominion Line, 1890s

Dominion Line, 1890s.jpg.webp) Inman Line, 1870

Inman Line, 1870 Inman Line, 1876

Inman Line, 1876 Inman Line, 1877

Inman Line, 1877

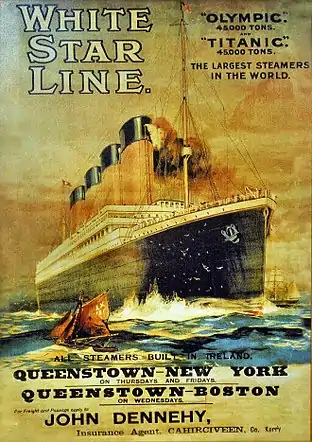

White Star Line and White-Star Dominion Line, routes 1923

White Star Line and White-Star Dominion Line, routes 1923 White Star Line 1910s

White Star Line 1910s

.jpg.webp)

Originally, the Prince's Landing Stage was situated at the Pier Head to serve the trans-Atlantic liner service. There were a number of these stages built during Liverpool's history, the most recent opened in the 1890s and was joined to the neighbouring George's Landing Stage, situated to the south. After further lengthening took place in the early twentieth century, the combined structure originally measured 2,478 feet, almost half a mile. Both were scrapped in 1973, following the termination of trans-Atlantic services from Liverpool.[9]

Mersey Ferries

The Mersey Ferries operate from George's Landing Stage, owned by the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company. Ferries travel to Woodside in Birkenhead and Seacombe in Wallasey.

Only a few months after a new stage (to replace the previous combined structure) was opened on 13 July 1975, it had to be refloated, after sinking in freak weather.[9] Similar conditions, and an extremely low tide on 2 March 2006, caused it to sink again, probably because one of its girder's air pockets ruptured, and it could not be refloated.[10] A temporary landing stage was installed until early 2010, when work began on a new Mersey Ferries landing stage. Mersey Ferries services switched to the Cruise Terminal. Services to Liverpool had to be suspended on 14 occasions during the year when large cruise ships were visiting.[11]

A brand new dedicated landing stage for the ferry was towed into place in November 2011, with the linkspan bridge being craned into place shortly after.[12] The new landing stage was officially opened in January 2012, with services resuming on 9 January.[13]

Isle of Man Ferry

The Isle of Man Steam Packet ferry service also operates from Princes Landing Stage, at a berth adjacent to those used by the Mersey Ferries.

Land transport

In addition to the Mersey Ferries, the Pier Head previously served as a major tram and later bus interchange.

Merseyrail's James Street station is a short walk away. The station was formerly part of the Mersey Railway. The Pier Head was also originally served by Liverpool Riverside station, connecting to main line services via the Victoria tunnel, and Pier Head station, on the Liverpool Overhead Railway. Both have since been demolished.

Open space

The open space at the Pier Head has also seen several developments. In the 1960s the area was given over to a bus terminal; in 1963 the terminal building for the Mersey Ferry was refurbished to include an adjoining restaurant. In 1991 the ferry terminal itself was reconfigured to its present style.

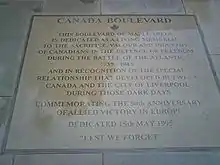

Running the length of the plaza is the Canada Boulevard, a walkway containing memorial plaques in memory of Canadians who gave their life in the Battle of the Atlantic.

In the centre of the space is an equestrian statue of Edward VII, dating from 1921.

Memorials

The space also contains a number of memorials; Clockwise from the north are:-

- The Titanic Memorial, to the engineers who remained at their posts during the sinking of the RMS Titanic,

- the Cunard War Memorial.

- the Memorial of Sir Alfred Lewis Jones

- the Merchant Navy war memorial.

There are several recent additions to the memorials at the Pier Head. In 2013, memorials were unveiled to the Second World War convoy escort group commander Captain Johnnie Walker and to the RMS Lancastria.[14][15] The Chinese Merchant Seamen's Memorial, remembering the Chinese merchant seamen who served and died for Britain in both World Wars, was unveiled on 23 January 2006.[16][17]

References

- "Great Britain: OS Six Inch, 1888-1913". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Sharples & Pollard 2004, p. 67

- "Liverpool – Maritime Mercantile City". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- "Liverpool World Heritage City". Liverpool City Council. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- De Figueiredo Peter. "Symbols of Empire: The Buildings of the Liverpool Waterfront", Architectural History, Vol. 46 (2003), pp. 229–254 (subscription required)

- "Fourth Grace plans 'unworkable'". BBC News. 19 July 2004.

- "Museum of Liverpool opens to the public".

- Books Magazine, Volumes 12-17, 1998, p.18

- Maund 1991

- "18-month wait for new landing stage". Trinity Mirror North West & North Wales Ltd. 13 April 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2006.

- "Changes to Mersey ferry services". BBC. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "New Mersey Ferry landing stage towed in place". BBC. 6 November 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "Mersey ferry terminal opens to passengers at Pier Head". BBC. 9 January 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Lancastria plaque unveiled". Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Lancastria victims remembered

- "Liverpool Pier Head Memorials". John H. Luxton. 2006. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Castle, Jody-Lan (25 August 2015). "Looking for my Shanghai father". BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2020.