Thylacoleo

Thylacoleo ("pouch lion") is an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the late Pleistocene (2 million to 46 thousand years ago). Some of these marsupial lions were the largest mammalian predators in Australia of their time, with Thylacoleo carnifex approaching the weight of a lioness. The estimated average weight for the species ranges from 101 to 130 kg (223 to 287 lb).[1]

| Thylacoleo Temporal range: late Pliocene—late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

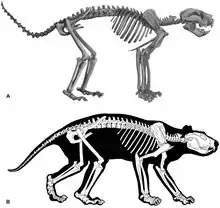

| Skeletal diagram of T. carnifex (top) and restored musculature based on living marsupials (bottom) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | †Thylacoleonidae |

| Genus: | †Thylacoleo Owen, 1859 |

| Type species | |

| †Thylacoleo carnifex | |

| Species | |

| |

Taxonomy

The genus was first published in 1859, erected to describe the type species Thylacoleo carnifex. The new taxon was established in examination of fossil specimens provided to Richard Owen. The familial alliance takes its name from this description, the so-called marsupial lions of Thylacoleonidae.

The colloquial name "marsupial lion" alludes to the superficial resemblance to the placental lion and its ecological niche as a large predator. Contrary to its common name, Thylacoleo is not closely related to the modern lion (Panthera leo).

Genus: Thylacoleo (Thylacopardus) – Australia's marsupial lions, that lived from about 2 million years ago, during the Late Pliocene Epoch and became extinct about 30,000 years ago, during the Late Pleistocene Epoch. Three species are known:

- Thylacoleo carnifex The holotype cranium was collected from Lake Colongulac in 1843 by pastoralist William Adeney. A partial rostrum collected by Adeney in 1876 from the same locality would later be found to belong to the same individual.[2]

- Thylacoleo crassidentatus lived during the Pliocene, around 5 million years ago, and was about the size of a large dog. Its fossils have been found in southeastern Queensland.[3][4]

- Thylacoleo hilli lived during the Pliocene and was half the size of T. crassidentatus. It is the oldest member of the genus.[5]

Fossils of other representatives of Thylacoleonidae, such as Microleo and Wakaleo, date back to the Late Oligocene Epoch, some 24 million years ago.[6]

T. hilli was described by Neville Pledge in a study published in the records of the South Australia Museum in 1977. The holotype is a third premolar, discovered at a cave in Curramulka in South Australia, exhibiting the carnivorous characteristics of the genus and around half the size of T. carnifex. This tooth was collected by Alan Hill, a speleologist and founding member of the Cave Exploration Group of South Australia, while examining a site known as the "Town Cave" in 1956; the specific epithet hilli honours the collector of the first specimen.[5] Material found amidst the fauna at Bow River in New South Wales, dated to the early Pliocene, was also referred to the species in 1982. [7] A fragment of an incisor, unworn and only diagnosable to the genus, was located at a site in Curramulka, close to the Town Cave site, and referred to the species for the apparent correlation in size when compared to the better known T. carnifex.[8]

The marsupial lion is classified in the order Diprotodontia along with many other well-known marsupials such as kangaroos, possums, and the koala. It is further classified in its own family, the Thylacoleonidae, of which three genera and 11 species are recognised, all extinct. The term marsupial lion (lower case) is often applied to other members of this family. Distinct possum-like characteristics led Thylacoleo to be regarded as members of Phalangeroidea for a few decades. Though a few authors continued to hint at phalangeroid affinities for thylacoleonids as recently as the 1990s, cranial and other characters have generally led to their inclusion within vombatiformes, and as stem-members of the wombat lineage.[9] Marsupial lions and other ecologically and morphologically diverse vombatiforms were once represented by over 60 species of carnivorous, herbivorous, terrestrial and arboreal forms ranging in size from 3 kg to 2.5 tonnes. Only two families represented by four herbivorous species (koalas and three species of wombat) have survived into modern times and are considered the marsupial lion's closest living relatives.[10]

Evolution

The ancestors of thylacoleonids are believed to have been herbivores, something unusual for carnivores. They are members of the Vombatiformes, an almost entirely herbivorous order of marsupials, the only extant representatives of which are koalas and wombats, as well as extinct members such as the diprotodontids and palorchestids.[11] The group first appeared in the Late Oligocene. The earliest thylacoleonids like Microleo were small possum-like animals,[12] with the group increasing in size during the Miocene, with representatives like the leopoard sized Wakaleo. The genus Thylacoleo first appeared during the Pliocene, and represented the only extant genus of the family from that time until the end of the Pleistocene. The youngest representative of Thylacoleo and the thylacoleonids, T. carnifex, is the largest known member of the family.[11]

Description

T. carnifex is the largest carnivorous mammal known to have ever existed in Australia, and one of the larger metatherian carnivores of the world (comparable to Thylacosmilus and Borhyaena species, but smaller than Proborhyaena gigantea). Individuals ranged up to around 75 cm (30 in) high at the shoulder and about 150 cm (59 in) from head to tail. Measurements taken from a number of specimens show they averaged 101 to 130 kg (223 to 287 lb) in weight, although individuals as large as 124–160 kg (273–353 lb) might not have been uncommon, and the largest weight was of 128–164 kg (282–362 lb).[13] This would make it comparable to female lions and female tigers in general size.

Bite

Pound for pound, T. carnifex had the strongest bite of any mammal species, living or extinct; a T. carnifex weighing 101 kg (223 lb) had a bite comparable to that of a 250 kg African lion, and research suggests that Thylacoleo could hunt and take prey much larger than itself.[14] Larger animals that were likely prey include Diprotodon spp. and giant kangaroos. It seems improbable that Thylacoleo could achieve as high a bite force as a modern-day lion; however, this might have been possible when taking into consideration the size of its brain and skull. Carnivores usually have rather large brains when compared to herbivorous marsupials, which lessens the amount of bone that can be devoted to enhancing bite force. Thylacoleo however, is thought to have had substantially stronger muscle attachments and therefore a smaller brain.[15]

Using 3D modeling based on X-ray computed tomography scans, marsupial lions were found to be unable to use the prolonged, suffocating bite typical of living big cats. They instead had an extremely efficient and unique bite; the incisors would have been used to stab at and pierce the flesh of their prey while the more specialised carnassials crushed the windpipe, severed the spinal cord, and lacerated the major blood vessels such as the carotid artery and jugular vein. Compared to an African lion which may take 15 minutes to kill a large catch, the marsupial lion could kill a large animal in less than a minute. The skull was so specialized for big game that it was very inefficient at catching smaller animals, which possibly contributed to its extinction.[16][17]

Postcranium

.jpg.webp)

Thylacoleo had extremely strong forelimbs, with retractable, cat-like claws, a trait previously unseen in marsupials. Thylacoleo also possessed enormous hooked claws set on large semi-opposable thumbs, which were used to capture and disembowel prey. The long muscular tail was similar to that of a kangaroo. Specialised tail bones called chevrons allowed the animal to balance on its back legs, and freed the front legs for slashing and grasping.[18]

Retractable claws would remain sharp by protecting them from being worn down on hard surfaces. The first digits ("thumbs") on each hand were semi-opposable and bore an enlarged claw. Palaeontologists believe this would have been used to grapple its intended prey, as well as providing it with a sure footing on tree trunks and branches. The hind feet had four functional toes, the first digit being much reduced in size, but possessing a roughened pad similar to that of possums, which may have assisted with climbing. The discovery in 2005 of a specimen which included complete hind feet provided evidence that the marsupial lion exhibited syndactyly (fused second and third toes) like other diprotodonts.[19]

Its strong forelimbs and retracting claws mean that Thylacoleo possibly climbed trees and perhaps carried carcasses to keep the kill for itself (similar to the leopard today).[20] The climbing ability would have also helped them climb out of caves, which could therefore have been used as dens to rear their young.[21]

Due to its unique predatory morphology, some scientists have claimed Thylacoleo to be the most specialised mammalian carnivore of all time.[22] Thylacoleo had vertical shearing 'carnassial' cheek teeth that are relatively larger than in any other mammalian carnivore.[14] Thylacoleo was clearly derived from the diprotodontian ancestry due to its incisor morphology and is distinguished by the pronounced development of upper and lower third premolars which functioned as extreme carnassials with complementary reduction in the molar teeth row.[23] They also had canines but they served little purpose as they were stubby and not very sharp.[24]

Behaviour and diet

Diet

When Thylacoleo was first described by Richard Owen, he considered it to be a carnivore, based on the morphology of its skull and teeth.[25] However other anatomists, such as William Henry Flower disagreed. Flower was the first to place Thylacoleo with the Diprotodonts, noting its skull and teeth to be laid out more like those of the koala and the wombat, and suggested that it was more likely a herbivore. Owen did not disagree with Flower's placement of Thylacoleo with the Diprotodonts, but still maintained that it was a carnivore, despite its herbivorous ancestry.[26] Owen found little support in his lifetime, despite the pointing out of Thylacoleo's retractable claws, something only found in mammalian carnivores,[27] and its lack of any ability to chew plant material.[26] In 1911, a study by Spencer and Walcott claimed that certain marks on the bones of megafauna had been made by Thylacoleo, but according to Horton (1979) they were not sufficiently rigorous, resulting in their arguments being strongly challenged by later scholars, such as Anderson (1929), and later Gill (1951, 1952, 1954), thereby leaving the issue unresolved.[28] In 1981, another paper was published arguing that certain cuts to bones of large marsupials had been caused by Thylacoleo. This paper by Horton and Wright was able to counter earlier arguments that such marks were the result of humans, largely by pointing out the presence of similar marks on the opposite side of many bones. They concluded that humans were extremely unlikely to have made the marks in question, but that if so "they had set out to produce only marks consistent with what Thylacoleo would produce".[28] Since then, the academic consensus has emerged that Thylacoleo was a predator and a hypercarnivore.[29]

Besides the most common hypothesis that it was an active predator, a variety of other theories existed in the late 19th to early 20th centuries as to the diet and feeding of Thylacoleo, with hypotheses of it being a scavenger filling the ecological niche of hyenas,[30] being a specialist of crocodile eggs,[20] or even a melon-eater.[31] As late as 1954, doubts were still being raised as to whether it was actually a hypercarnivore.[29]

The marsupial lion's limb proportions and muscle mass distribution indicate that, although it was a powerful animal, it was not a particularly fast runner. Paleontologists conjecture that it was an ambush predator, either sneaking up and then leaping upon its prey, or dropping down on it from overhanging tree branches. This is consistent with the depictions of the animal as striped: camouflage of that kind is needed for stalking and hiding in a largely forested habitat (like tigers) rather than chasing across open spaces (like lions).[32] Trace fossils in the form of claw marks and bones from caves in Western Australia analyzed by Gavin Prideaux et al. indicate marsupial lions could also climb rock faces, and likely reared their young in such caves as a way of protecting them from potential predators.[33] It is thought to have hunted large animals such as the enormous Diprotodon and giant browsing kangaroos like Sthenurus and Procoptodon, and competed with other predatory animals such as the giant monitor lizard, Megalania, and terrestrial crocodiles such as Quinkana. The marsupial lion may have cached kills in trees in a manner similar to the modern leopard.[34] Like many predators, it was probably also an opportunistic scavenger, feeding on carrion and driving off less powerful predators from their kills. It also may have shared behaviours exhibited by recent diprotodont marsupials such as kangaroos, like digging shallow holes under trees to reduce body temperature during the day.[35]

Senses

CT scans of a well-preserved skull have allowed scientists to study internal structures and create a brain endocast showing the surface features of the animal's brain. The parietal lobes, visual cortex, and olfactory bulbs of the cerebrum were enlarged, indicating the marsupial lion had good senses of hearing, sight, and smell, as might be expected of an active predator. Also, a pair of blind canals within the nasal cavity were probably associated with detecting pheromones as in the Tasmanian devil. This indicates it most likely had seasonal mating habits and would "sniff out" a mate when in season.[36]

Feeding

The feeding behaviour of Thylacoleo remains a topic of academic debate, largely due the lack of any living analogue.[29] While considered a powerful hunter, and a fierce predator, it has been theorized that due to its physiology Thylacoleo was, in fact, a slow runner, limiting its ability to chase prey. Analysis of its scapula suggests "walking and trotting, rather than climbing ... the pelvis similarly agrees with that of ambulators and cursors [walkers and runners]". These bones indicate that Thylacoleo was a slow to medium-paced runner, which is likely to mean it was an ambush predator. That fits with the stripes: camouflage of the kind one would need for stalking and hiding in a largely forested habitat (like tigers or leopards) rather than chasing across open spaces (like lions)."[37] It may have functioned generally much like a larger analog of the Tasmanian devil.[21] New evidence also suggests that it may have been arboreal, and was at the very least capable of climbing trees.[20]

Incisions on bones of Macropus titan, and the general morphology of Thylacoleo suggests that it fed in a similar manner to modern cheetahs, by using their sharp teeth to slice open the ribcage of their prey, thereby accessing the internal organs. They may have killed by using their front claws as either stabbing weapons or as a way to grab their prey with strangulation or suffocation.[28]

Palaeoecology

.jpg.webp)

Numerous fossil discoveries indicate the marsupial lion was distributed across much of the Australian continent. A large proportion of its environment would have been similar to the southern third of Australia today, semiarid, open scrub and woodland punctuated by waterholes and water courses.

It would have coexisted with many of the so-called Australian megafauna such as Diprotodon, giant kangaroos, and Megalania, as well as giant wallabies like Protemnodon, the giant wombat Phascolonus, the giant snake Wonambi, and the thunderbird Genyornis.[36] T. hilli was a similar size to a contemporaneous thylacoleonid species, Wakaleo alcootaensis, and may have occupied habitat to the exclusion of that carnivore.[38]

Australia's Pleistocene megafauna would have been the prey for the agile T. carnifex, who was especially adapted for hunting large animals, but was not particularly suited to catching smaller prey. The relatively quick reduction in the numbers of its primary food source around 40,000 to 50,000 years ago probably led to the decline and eventual extinction of the marsupial lion. The arrival of humans in Australia and the use of fire-stick farming precipitated their decline.[39] The extinction of T. carnifex makes Australia unique from the other continents because no substantial, apex mammalian predators have replaced the marsupial lions after their disappearance.[40]

Extinction

It was believed that the extinction was due to the climate changes, but human activities as an extinction driver of the most recent species is possible yet unproven. There is a growing consensus that the extinction of the megafauna was caused by progressive drying starting about 700,000 years ago (700 ka). It is revealed recently that there was a major change in glacial-interglacial cycles after ~450 ka. As for human involvement's contribution to the extinction, one argument is that the arrival of humans was coincident with the disappearance of all the extinct megafauna. This is supported by the claims that during MIS3, climatic conditions are relatively stable and no major climate change would cause the mass extinction of megafauna including Thylacoleo.[41]

Although believed to have been a victim of climate change, some scientists now believe Thylacoleo to have been exterminated by humans altering the ecosystem with fire in addition to hunting its prey. "They found Sporormiella spores, which grow in herbivore dung, virtually disappeared around 41,000 years ago, a time when no known climate transformation was taking place. At the same time, the incidence of fire increased, as shown by a steep rise in charcoal fragments. It appears that humans, who arrived in Australia around this time, hunted the megafauna to extinction".[42] Following the extinction of T. carnifex, no other apex mammalian predators have taken its place.[43]

Discoveries

The first specimens of Thylacoleo were collected in the early 1830s from the Wellington Valley region of New South Wales by Major (later Sir) Thomas Mitchell, however they were not recognised as Thylacoleo at the time.[24]

The species was first described by Richard Owen in 1859,[24] from a fragmentary specimen discovered by William Adeney near Lake Colungolac, near Camperdown in Victoria[25]

In 2002, eight remarkably complete skeletons of T. carnifex were discovered in a limestone cave under Nullarbor Plain, where the animals fell through a narrow opening in the plain above. Based on the placement of their skeletons, at least some survived the fall, only to die of thirst and starvation.[44][45]

In 2008, rock art depicting what some speculate to be Thylacoleo was discovered on the northwestern coast of the Kimberley. However, the thylacine, a marsupial that had a striped coat like depicted in the rock art, has been argued to be the more likely subject of the work.[46] The drawing represented only the second example of megafauna depicted by the indigenous inhabitants of Australia. The image contains details that would otherwise have remained only conjecture; the tail is depicted with a tufted tip, it has pointed ears rather than rounded, and the coat is striped. The prominence of the eye, a feature rarely shown in other animal images of the region, raises the possibility that the creature may have been a nocturnal hunter.[47] In 2009, a second image was found that depicts a Thylacoleo interacting with a hunter who is in the act of spearing or fending the animal off with a multiple-barbed spear. Much smaller and less detailed than the 2008 find, it may depict a thylacine, but the comparative size indicates a Thylacoleo is more likely, meaning that it is possible that Thylacoleo was extant until more recently than previously thought.[48]

In 2016, trace fossils in Tight Entrance Cave were identified as being the scratch marks of a Thylacoleo.[20]

Fossils

The first Thylacoleo fossil findings, discovered by Thomas Mitchell were found in the 1830s in the Wellington Valley of New South Wales, though not recognised as such at the time. The generic holotype, consisting of broken teeth, jaws, and a skull was discovered by a pastoralist, William Avery, near Lake Colungolac from which the species Thylacoleo carnifex was described by Richard Owen.[25] It was not until 1966 that the first nearly-complete skeleton was found. The only pieces missing were a foot and the tail. Currently, the Nullarbor Plain of West Australia remains to be the greatest finding site. These fossils now reside at the Australian Museum.[49][27]

It was reported that in 2012, an accumulation of vertebrate trace and body fossils were found in the Victorian Volcanic Plains in southeastern Australia. It was determined that Thylacoleo was the only taxon that represented three divergent fossil records: skeletal, footprints, and bite marks. What this suggests is that these large carnivores had behavioral characteristics that could have increased their likelihood of their presence being detected within a fossil fauna.[50]

A characteristic seen in the remains of skull fragments is a set of carnassial teeth, suggesting the carnivorous habits of Thylacoleo. Tooth fossils of the Thylacoleo exhibit specific degrees of erosion that are credited to the utility of the carnassial teeth remains as they were used for hunting and consuming prey in a prehistoric Australia teeming with other megafauna. The specialisation found in the dental history of the marsupial indicates its status in the predatory hierarchy in which it existed.[51]

References

- Alloing-Séguier, Léanie; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R.; Lee, Michael S. Y.; Lebrun, Renaud (2013). "The Bony Labyrinth in Diprotodontian Marsupial Mammals: Diversity in Extant and Extinct Forms and Relationships with Size and Phylogeny". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 20 (3): 191–198. doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9228-3. S2CID 16385939.

- Gill, E.D. (25 February 1973). "Antipodal distribution of the holotype bones of Thylacoleo carnifex Owen (Marsupialia)". Science Reports of the Tohoku University. Second Series, Geology. 6: 497–499. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Woods, J. T. (1956). "The skull of Thylacoleo carnifex". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 13: 125–140.

- Bartholomai, Alan (1962). "A new species of Thylacoleo and notes on some caudal vertebrae of Palorchestes azael". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 14: 33–40.

- Pledge, N.S. (1977). "A new species of Thylacoleo (Marsupialia: Thylacoleonidae) with notes on the occurrences and distribution of Thylacoleonidae in South Australia". Records of the South Australian Museum. 17: 277–283.

- Long, J.A., Archer, M., Flannery, T. & Hand, S. (2002). Prehistoric Mammals of Australia and New Guinea - 100 million Years of Evolution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 224pp.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Flannery, T.F.; Archer, M. (1984). "The macropodoids (Marsupialia) of the Early Pliocene Bow local fauna, central eastern New South Wales". The Australian Zoologist. 21: 357–383.

- Pledge, Neville S. (1992). "The Curramulka local fauna: A new late Tertiary fossil assemblage from Yorke Peninsula, South Australia". The Beagle: Occasional Papers of the Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences. 9: 115–142.

- Naish, Darren (2004). "Of koalas and marsupial lions: the vombatiform radiation, part I". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 33 (1): 240–250. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.004. PMID 15324852. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Black, Karen; Price, Gilbert J; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J (2014). "Bearing up well? Understanding the past, present and future of Australia's koalas". Gondwana Research. 25 (3): 1186–201. Bibcode:2014GondR..25.1186B. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.12.008.

- Black, K. H.; Archer, M.; Hand, S. J.; Godthelp, H. (2012). "The Rise of Australian Marsupials: A Synopsis of Biostratigraphic, Phylogenetic, Palaeoecologic and Palaeobiogeographic Understanding". In Talent, J. A. (ed.). Earth and Life. Springer Verlag. pp. 1040, 1047. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3428-1_35. ISBN 978-90-481-3427-4.

- Gillespie, Anna K; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J (2016). "A tiny new marsupial lion (Marsupialia, Thylacoleonidae) from the early Miocene of Australia". Palaeontologia Electronica. 19 (2). doi:10.26879/632.

- Wroe, S; Myers, T. J; Wells, R. T; Gillespie, A (1999). "Estimating the weight of the Pleistocene marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex (Thylacoleonidae:Marsupialia): Implications for the ecomorphology of a marsupial super-predator and hypotheses of impoverishment of Australian marsupial carnivore faunas". Australian Journal of Zoology. 47 (5): 489–98. doi:10.1071/ZO99006.

- Wroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2005). "Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1563): 619–625. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMC 1564077. PMID 15817436.

- Switek, Brian (31 August 2007). "Thylacoleo carnifex, ancient Australia's marsupial lion". Laelaps. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Extinct Marsupial Lion Tops African Lion In Fight To Death", Science Daily, 17 January 2008.

- Dayton, Leigh (18 January 2008). "Marsupial lion was fast killer". The Australian. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009.

- "NOVA | Bone Diggers | Anatomy of Thylacoleo | PBS". www.pbs.org.

- Wells, R.T.; Murray, P.F.; Bourne, S.J. (2009). "Pedal morphology of the marsupial lion Thylacoleo carnifex (Diprotodontia: Thylacoleonidae) from the Pleistocene of Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1335–1340. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1335W. doi:10.1671/039.029.0424. S2CID 86460654.

- Arman, Samuel D.; Prideaux, Gavin J. (15 February 2016). "Behaviour of the Pleistocene marsupial lion deduced from claw marks in a southwestern Australian cave". Scientific Reports. 6: 21372. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621372A. doi:10.1038/srep21372. PMC 4753435. PMID 26876952. S2CID 3548956.

- Evans, A. R.; Wells, R. T.; Camens, A. B. (2018). "New skeletal material sheds light on the palaeobiology of the Pleistocene marsupial carnivore, Thylacoleo carnifex". PLOS ONE. 13 (12): e0208020. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1308020W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208020. PMC 6291118. PMID 30540785.

- "Extinct Australian "Lion" Was Big Biter, Expert Says".

- Wells, Roderick T.; Murray, Peter F.; Bourne, Steven J. (2009). "Pedal morphology of the marsupial lion Thylacoleo carnifex (Diprotodontia: Thylacoleonidae) from the Pleistocene of Australia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1335–1340. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29.1335W. doi:10.1671/039.029.0424. S2CID 86460654.

- "Discovery and Interpretation". Natural Worlds. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- "XVI. On the fossil mammals of Australia.— Part I. Description of a mutilated skull of a large marsupial carnivore (Thylacoleo carnifex, Owen), from a calcareous conglomerate stratum, eighty miles S. W. Of Melbourne, Victoria". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 149: 309–322. 1859. doi:10.1098/rstl.1859.0016. S2CID 110651400.

- Switek, Brian. "Thylacoleo: Herbivore or Carnivore?". Wired.

- "XV. On the affinities of thylacoleo". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 174: 575–582. 1883. doi:10.1098/rstl.1883.0015. ISSN 0261-0523. S2CID 111347165.

- Horton, D. R.; Wright, R. V. S. (1981). "Cuts on Lancefield Bones: Carnivorous Thylacoleo, Not Humans, the Cause". Archaeology in Oceania. 16 (2): 73–80. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1981.tb00009.x. JSTOR 40386545.

- Figueirido, Borja; Martín-Serra, Alberto; Janis, Christine M. (2016). "Ecomorphological determinations in the absence of living analogues: The predatory behavior of the marsupial lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) as revealed by elbow joint morphology" (PDF). Paleobiology. 42 (3): 508–531. Bibcode:2016Pbio...42..508F. doi:10.1017/pab.2015.55. S2CID 87168573.

- De Vis, C. W. (1883). "On tooth-marked bones of extinct marsupials". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 8: 187–190. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.28646.

- Anderson, C. (1929). "Palaeontological notes no. 1. Macropus titan Owen and Thylacoleo carnifex Owen". Records of the Australian Museum. 17: 35–49. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.17.1929.752.

- Monbiot, George (2014-04-03). "'Like a demon in a medieval book': is this how the marsupial lion killed prey?". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- "Marsupial lion 'could climb trees'". BBC News. 2016-02-15.

- Western Australian Museum Thylacoleo (panel 3) Archived 2008-07-27 at the Wayback Machine at Western Australian Museum

- Tyndale-Biscoe, Hugh (2005). Life of marsupials. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-643-09220-4.

- Thylacoleo "The Beast of the Nullarbor", Catalyst, Western Australian Museum, Storyteller Media Group and ABC TV, 17 August 2006.

- Monbiot, George (2014-04-03). "'Like a demon in a medieval book': Is this how the marsupial lion killed prey?". The Guardian.

- Murray, P.; Megirian, D. (1990). "Further observations on the morphology of Wakaleo vanderleueri (Marsupialia:Thylacoleonidae) from the mid-Miocene Camfield beds, Northern Territory". The Beagle: Occasional Papers of the Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences. 7 (1): 91–102.

- "'Humans killed off Australia's giant beasts'". BBC News. 24 March 2012.

- Ritchie, Euan G; Johnson, Christopher N (2009). "Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation". Ecology Letters. 12 (9): 982–98. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01347.x. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30039763. PMID 19614756.

- "Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea)" (PDF).

- "Humans killed off Australia's giant beasts". BBC. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Ritchie, Euan G.; Johnson, Christopher N. (2009-09-01). "Predator interactions, mesopredator release and biodiversity conservation". Ecology Letters. 12 (9): 982–998. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01347.x. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30039763. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 19614756.

- "Caverns give up huge fossil haul". BBC News. 25 January 2007.

- "Australian Cave Yields Giant Animal Fossils". Archived from the original on 2009-05-24. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- Welch, David M. (June 2015). "Thy Thylacoleo is a thylacine". Australian Archaeology. 80 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1080/03122417.2015.11682043. ISSN 0312-2417. S2CID 146358676.

- Akerman, Kim; Willing, Tim (March 2009). "An ancient rock painting of a marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, from the Kimberley, Western Australia". Antiquity. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Akerman, Kim (December 2009). "Interaction between humans and megafauna depicted in Australian rock art?". Antiquity. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Musser, Anne (29 November 2018). "Thylacoleo carnifex". Australian Museum. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Camens, Aaron Bruce; Carey, Stephen Paul (2013-01-02). "Contemporaneous Trace and Body Fossils from a Late Pleistocene Lakebed in Victoria, Australia, Allow Assessment of Bias in the Fossil Record". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e52957. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...852957C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052957. PMC 3534647. PMID 23301008.

- "IV. On the fossil mammals of Australia. - Part II. Description of an almost entire skull of the thylacoleo carnifex, Owen, from a freshwater deposit, Darling Downs, Queensland". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 156: 73–82. 1866. doi:10.1098/rstl.1866.0004. S2CID 110169146.

External links

- New study finds no evidence for theory humans wiped out megafauna

- Thylacoleo - Australia's Marsupial Lion

- Thylacoleo in Pleistocene Australia

- Steve Wroe's Web Page: Australian Megafauna

- Western Australian Museum: Thylacoleo - a voracious hunter

- PLEDGE. N 1977, A NEW SPECIES OF THYLACOLEO (MARSUPIALIA: THYLACOLEONIDAE) WITH NOTES ON THE OCCURRENCES AND DISTRIBUTION OF THYLACOLEONIDAE IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA