Thyroid neoplasm

Thyroid neoplasm is a neoplasm or tumor of the thyroid. It can be a benign tumor such as thyroid adenoma,[1] or it can be a malignant neoplasm (thyroid cancer), such as papillary, follicular, medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.[2] Most patients are 25 to 65 years of age when first diagnosed; women are more affected than men.[2][3] The estimated number of new cases of thyroid cancer in the United States in 2010 is 44,670 compared to only 1,690 deaths.[4] Of all thyroid nodules discovered, only about 5 percent are cancerous, and under 3 percent of those result in fatalities.

| Thyroid neoplasm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Thyroid anatomy | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing a thyroid neoplasm is a physical exam of the neck area. If any abnormalities exist, a doctor needs to be consulted. A family doctor may conduct blood tests, an ultrasound, and nuclear scan as steps to a diagnosis. The results from these tests are then read by an endocrinologist who will determine what problems the thyroid has. Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism are two conditions that often arise from an abnormally functioning thyroid gland. These occur when the thyroid is producing too much or too little thyroid hormone respectively.[4]

Thyroid nodules are a major presentation of thyroid neoplasms, and are diagnosed by ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (USG/FNA) or frequently by thyroidectomy (surgical removal and subsequent histological examination). FNA is the most cost-effective and accurate method of obtaining a biopsy sample.[5] As thyroid cancer can take up iodine, radioactive iodine is commonly used to treat thyroid carcinomas, followed by TSH suppression by high-dose thyroxine therapy.

Nodules are of particular concern when they are found in those under the age of 20. The presentation of benign nodules at this age is less likely, and thus the potential for malignancy is far greater.

Classification

Thyroid neoplasm might be classified as benign or malignant.

Benign neoplasms

Thyroid adenoma is a benign neoplasm of the thyroid. Thyroid nodules are very common and around 80 percent of adults will have at least one by the time they reach 70 years of age. Approximately 90 to 95 percent of all nodules are found to be benign.[4]

Malignant neoplasms

Thyroid cancers are mainly papillary, follicular, medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.[2] Most patients are 25 to 65 years of age when first diagnosed; women are more affected than men.[2][3] Nearly 80 percent of thyroid cancer is papillary and about 15 percent is follicular; both types grow slowly and can be cured if caught early. Medullary thyroid cancer makes up about 3 percent of this cancer. It grows slowly and can be controlled if caught early. Anaplastic is the most deadly and makes up around 2 percent. This type grows quickly and is hard to control.[4] The classification is determined by looking at the sample of cells under a microscope and determining the type of thyroid cell that is present. Other thyroid malignancies include thyroid lymphoma, various types of thyroid sarcoma, smooth muscle tumors, teratoma, squamous cell thyroid carcinoma and other rare types of tumors.[6]

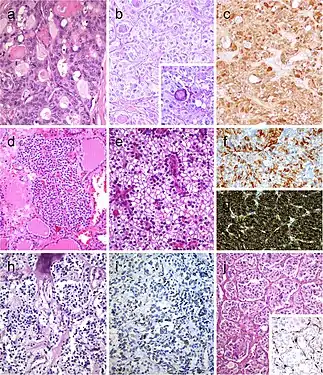

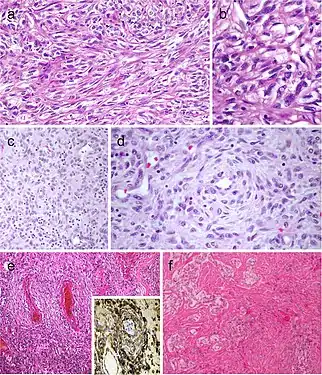

Carcinoma of the thyroid with Ewing family tumor elements (CEFTE) disclosing solid nests of small cells with regular, round nuclei, and nests of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (a). This case is from a 17-year-old female patient with bilateral involvement of the thyroid by a malignant thyroid teratoma (b); the tumor discloses nests of small cells, rich stroma with chondroid appearance and an epithelial-tubular component. Mixed medullary and papillary thyroid carcinoma (c); the medullary thyroid carcinoma component stained positively for calcitonin mRNA while the PTC (follicular variant) component was negative (d). Intrathyroid thymic carcinoma (ITC) also known by the acronym (CASTLE) showing positivity for CD5 (inset) (e). Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE) is a lobulated tumor composed of spindle cells and epithelioid cell component with glands, mucinous cysts, and/or squamous nests (f and g)[7]

Carcinoma of the thyroid with Ewing family tumor elements (CEFTE) disclosing solid nests of small cells with regular, round nuclei, and nests of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (a). This case is from a 17-year-old female patient with bilateral involvement of the thyroid by a malignant thyroid teratoma (b); the tumor discloses nests of small cells, rich stroma with chondroid appearance and an epithelial-tubular component. Mixed medullary and papillary thyroid carcinoma (c); the medullary thyroid carcinoma component stained positively for calcitonin mRNA while the PTC (follicular variant) component was negative (d). Intrathyroid thymic carcinoma (ITC) also known by the acronym (CASTLE) showing positivity for CD5 (inset) (e). Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE) is a lobulated tumor composed of spindle cells and epithelioid cell component with glands, mucinous cysts, and/or squamous nests (f and g)[7] Follicular patterned medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) (a). In this other follicular patterned MTC (b), there are several calcifications simulating psammoma bodies (inset) and positivity for calcitonin (c). Intrathyroidal parathyroid tissue (d). The microscopic aspect of an intrathyroidal parathyroid adenoma is similar to eutopic parathyroid adenomas (e). Intrathyroidal parathyroid adenoma expressing chromogranin A (f) and PTH (g). Calcitonin-negative medullary thyroid carcinoma (h) showing positivity for CGRP (i). Paraganglioma (j) typically shows negativity for calcitonin and S100-positive sustentacular cells (inset)[7]

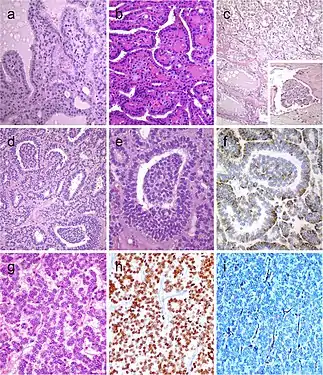

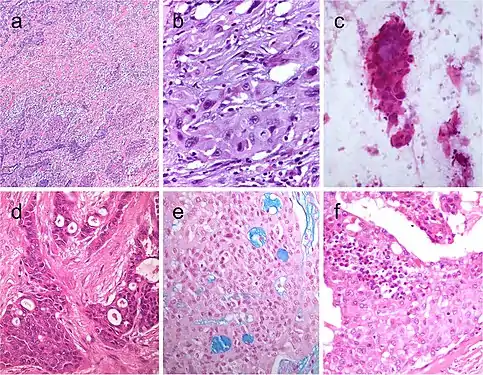

Follicular patterned medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) (a). In this other follicular patterned MTC (b), there are several calcifications simulating psammoma bodies (inset) and positivity for calcitonin (c). Intrathyroidal parathyroid tissue (d). The microscopic aspect of an intrathyroidal parathyroid adenoma is similar to eutopic parathyroid adenomas (e). Intrathyroidal parathyroid adenoma expressing chromogranin A (f) and PTH (g). Calcitonin-negative medullary thyroid carcinoma (h) showing positivity for CGRP (i). Paraganglioma (j) typically shows negativity for calcitonin and S100-positive sustentacular cells (inset)[7] Hyperfunctioning follicular adenoma typically shows follicles with papillary infoldings and bubbly, pale colloid with peripheral scalloping (a). Non-hyperfunctioning adenomas with papillary hyperplasia usually show a more predominantly papillary pattern without vacuolated cytoplasm and scalloping colloid (b). Rare hyperfunctioning follicular tumors (c) can show capsular and/or venous invasion (inset); the nuclei are very clear which may be associated to hyperfunctioning. The glomeruloid pattern in this follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) included follicles with round to oval tufts growing within, at times supported by a fibrovascular core mimicking the renal glomerulus (d and e); empty follicles were lined by columnar cells with marked pseudostratification, and positivity for CK18 was detected (f). FTC (g) with TTF1 expression (h) and very focal expression of thyroglobulin i[7]

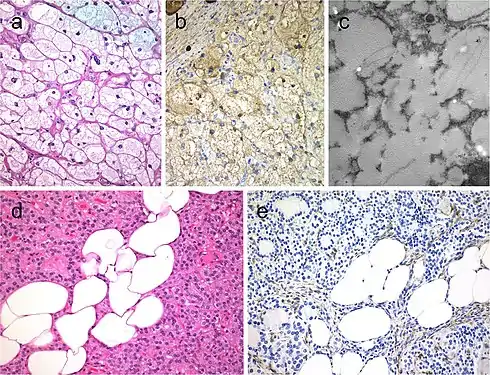

Hyperfunctioning follicular adenoma typically shows follicles with papillary infoldings and bubbly, pale colloid with peripheral scalloping (a). Non-hyperfunctioning adenomas with papillary hyperplasia usually show a more predominantly papillary pattern without vacuolated cytoplasm and scalloping colloid (b). Rare hyperfunctioning follicular tumors (c) can show capsular and/or venous invasion (inset); the nuclei are very clear which may be associated to hyperfunctioning. The glomeruloid pattern in this follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) included follicles with round to oval tufts growing within, at times supported by a fibrovascular core mimicking the renal glomerulus (d and e); empty follicles were lined by columnar cells with marked pseudostratification, and positivity for CK18 was detected (f). FTC (g) with TTF1 expression (h) and very focal expression of thyroglobulin i[7] Lipid-rich follicular thyroid carcinoma (a) immunoreactive for thyroglobulin (b); the ultrastructural study evidenced numerous lipid vacuoles in the cytoplasm (ultrastructure) (c). Adenolipoma (lipoadenoma) in a patient with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (d); there is negativity for PTEN protein in tumor cells while stromal cells (internal positive control) are positive (e)[7]

Lipid-rich follicular thyroid carcinoma (a) immunoreactive for thyroglobulin (b); the ultrastructural study evidenced numerous lipid vacuoles in the cytoplasm (ultrastructure) (c). Adenolipoma (lipoadenoma) in a patient with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (d); there is negativity for PTEN protein in tumor cells while stromal cells (internal positive control) are positive (e)[7] Medullary thyroid carcinoma with papillary pattern (a). Solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (b) with focal expression of thyroglobulin (c) and expression of T4 (d); in this case, TTF1 was diffusely expressed. Biphasic Hürthle cell (oncocytic) clear carcinoma in which the basal half of the cytoplasm is oncocytic, whereas the upper half is clear (e), due to the swelling of the mitochondria (ultrastructure) (f)[7]

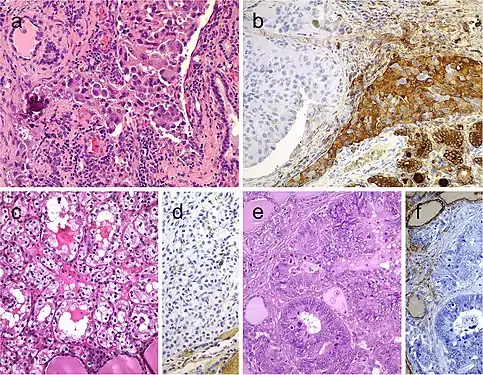

Medullary thyroid carcinoma with papillary pattern (a). Solid variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (b) with focal expression of thyroglobulin (c) and expression of T4 (d); in this case, TTF1 was diffusely expressed. Biphasic Hürthle cell (oncocytic) clear carcinoma in which the basal half of the cytoplasm is oncocytic, whereas the upper half is clear (e), due to the swelling of the mitochondria (ultrastructure) (f)[7] Metastatic carcinomas in the thyroid gland. Thyroid metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma (a, b). Some metastatic tumor cells (right) are positive for thyroglobulin due to diffusion artifact and should not be overinterpreted as positive (b). Metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma (c), metastatic renal cells are negative for thyroglobulin (d). Colonic adenocarcinoma metastatic to the thyroid gland (e); the thyroid tissue is positive for thyroglobulin while the metastatic adenocarcinoma is negative (f)[7]

Metastatic carcinomas in the thyroid gland. Thyroid metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma (a, b). Some metastatic tumor cells (right) are positive for thyroglobulin due to diffusion artifact and should not be overinterpreted as positive (b). Metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma (c), metastatic renal cells are negative for thyroglobulin (d). Colonic adenocarcinoma metastatic to the thyroid gland (e); the thyroid tissue is positive for thyroglobulin while the metastatic adenocarcinoma is negative (f)[7] Mucinous thyroid carcinoma (a) showing abundant mucoid material mucicarmine positive (b); most tumor cells were positive for thyroglobulin (c). In this mucinous variant of follicular thyroid carcinoma (d), the follicles were distended and full of Alcian blue–positive mucinous material (e). Mucinous variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (f), the tumor showed ribbon, trabecular and/or follicular pattern, classic nuclear features of PTC and abundant mucoid stroma positively stained with Alcian blue (g)[7]

Mucinous thyroid carcinoma (a) showing abundant mucoid material mucicarmine positive (b); most tumor cells were positive for thyroglobulin (c). In this mucinous variant of follicular thyroid carcinoma (d), the follicles were distended and full of Alcian blue–positive mucinous material (e). Mucinous variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (f), the tumor showed ribbon, trabecular and/or follicular pattern, classic nuclear features of PTC and abundant mucoid stroma positively stained with Alcian blue (g)[7] Spindle cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) showing spindle cells with typical PTC nuclei (a and b). Meningioma-like follicular adenoma (c and d), the typical arrangement of spindle to ovoid cells in a whorled pattern may give the impression one is dealing with a vascular tumor. Pericytic-like follicular adenoma (e) is characterized by a proliferation of spindle follicular cells concentrically arranged around vessels; the follicular nature of the tumor cells could be confirmed by the positivity for thyroglobulin (inset), thyroperoxidase, TTF1 and cytokeratins but negativity for calcitonin and CD31. PTC with fibromatosis/fasciitis-like stroma with both stromal and PTC component (f)[7]

Spindle cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) showing spindle cells with typical PTC nuclei (a and b). Meningioma-like follicular adenoma (c and d), the typical arrangement of spindle to ovoid cells in a whorled pattern may give the impression one is dealing with a vascular tumor. Pericytic-like follicular adenoma (e) is characterized by a proliferation of spindle follicular cells concentrically arranged around vessels; the follicular nature of the tumor cells could be confirmed by the positivity for thyroglobulin (inset), thyroperoxidase, TTF1 and cytokeratins but negativity for calcitonin and CD31. PTC with fibromatosis/fasciitis-like stroma with both stromal and PTC component (f)[7] Squamous cell tumor examples that include extensive squamous metaplasia in PTC after fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) (a), squamous cell carcinoma in the thyroid of putative secondary origin (b), and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus metastatic in the thyroid and diagnosed by FNAB (c). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (d) composed by solid sheets of epithelial cells showing epidermoid cells and glandular spaces containing mucinous material positively stained with Alcian blue (e). Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia showing epithelial cells richly infiltrated by eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (f)[7]

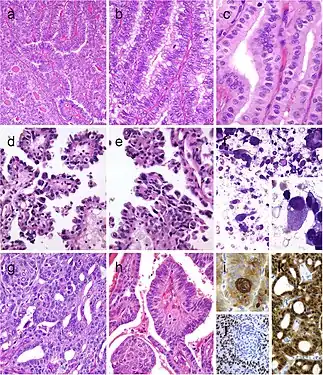

Squamous cell tumor examples that include extensive squamous metaplasia in PTC after fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) (a), squamous cell carcinoma in the thyroid of putative secondary origin (b), and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus metastatic in the thyroid and diagnosed by FNAB (c). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (d) composed by solid sheets of epithelial cells showing epidermoid cells and glandular spaces containing mucinous material positively stained with Alcian blue (e). Sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with eosinophilia showing epithelial cells richly infiltrated by eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (f)[7] Columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) showing a combination of papillary and glandular-like patterns (a), marked nuclear pseudostratification, and less nuclear features of classic PTC (b). In the tall cell variant of PTC, the cytoplasm is deeply eosinophilic, and nuclear features of PTC are very prominent with irregular contours and common pseudoinclusions (c). Hobnail variant of PTC combining papillary (d), and micropapillary (e) structures lined by hobnail cells. “Teardrop” cells (f) and comet-like cells (inset). The cribriform-morular thyroid carcinoma exhibits a blending of cribriform, papillary, trabecular, and solid pattern with morules (g) and (h). Morules are strongly positive for CD10 (i). Tumor cells are reactive for estrogen receptors (j), and there is strong nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity for β-catenin (k)[7]

Columnar cell variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) showing a combination of papillary and glandular-like patterns (a), marked nuclear pseudostratification, and less nuclear features of classic PTC (b). In the tall cell variant of PTC, the cytoplasm is deeply eosinophilic, and nuclear features of PTC are very prominent with irregular contours and common pseudoinclusions (c). Hobnail variant of PTC combining papillary (d), and micropapillary (e) structures lined by hobnail cells. “Teardrop” cells (f) and comet-like cells (inset). The cribriform-morular thyroid carcinoma exhibits a blending of cribriform, papillary, trabecular, and solid pattern with morules (g) and (h). Morules are strongly positive for CD10 (i). Tumor cells are reactive for estrogen receptors (j), and there is strong nuclear and cytoplasmic reactivity for β-catenin (k)[7] Tumor of the thyroid with solid cell nest features disclosing small cells of the main cell type (a) that express p63 (b) and cytokeratin 5 (c), in the absence of TTF1, calcitonin, and thyroglobulin expression. Hyalinizing trabecular tumor (d–f) is composed of trabeculae of elongated or polygonal cells admixed with abundant amounts of hyaline material negative for amyloid and positive for type IV collagen (f); Ki-67 is characteristically expressed in the cell membrane but not in the nuclei of the tumor cells (e). Follicular adenoma with signet ring cells (g and h), showing strong positivity for thyroglobulin (i)[7]

Tumor of the thyroid with solid cell nest features disclosing small cells of the main cell type (a) that express p63 (b) and cytokeratin 5 (c), in the absence of TTF1, calcitonin, and thyroglobulin expression. Hyalinizing trabecular tumor (d–f) is composed of trabeculae of elongated or polygonal cells admixed with abundant amounts of hyaline material negative for amyloid and positive for type IV collagen (f); Ki-67 is characteristically expressed in the cell membrane but not in the nuclei of the tumor cells (e). Follicular adenoma with signet ring cells (g and h), showing strong positivity for thyroglobulin (i)[7]

Treatment

Treatment of a thyroid nodule depends on many things including size of the nodule, age of the patient, the type of thyroid cancer, and whether or not it has spread to other tissues in the body. If the nodule is benign, patients may receive thyroxine therapy to suppress thyroid-stimulating hormone and should be reevaluated in six months.[2] However, if the benign nodule is inhibiting the patient's normal functions of life; such as breathing, speaking, or swallowing, the thyroid may need to be removed. Sometimes only part of the thyroid is removed in an attempt to avoid causing hypothyroidism. There is still a risk of hypothyroidism though, as the remaining thyroid tissue may not be able to produce enough hormones in the long-run.

If the nodule is malignant or has indeterminate cytologic features, it may require surgery.[2] A thyroidectomy is a medium-risk surgery that can result in complications if not performed correctly. Problems with the voice, nerve or muscular damage, or bleeding from a lacerated blood vessel are rare but serious complications that may occur. After removing the thyroid, the patient must be supplied with a replacement hormone for the rest of their life. This is commonly a daily oral medication prescribed by their endocrinologist.

Radioactive iodine-131 is used in patients with papillary or follicular thyroid cancer for ablation of residual thyroid tissue after surgery and for the treatment of thyroid cancer. Patients with medullary, anaplastic, and most Hurthle cell cancers do not benefit from this therapy.[2] External irradiation may be used when the cancer is unresectable, when it recurs after resection, or to relieve pain from bone metastasis.[2]

See also

References

- Chapter 20 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1. 8th edition.

- Hu MI, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Lustig R, Lamont JP. "Thyroid and Parathyroid Cancers" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 11 ed. 2008.

- Al-Zaher N, Al-Salam S, El Teraifi H. Thyroid carcinoma in the United Arab Emirates: perspectives and experience of a tertiary care hospital. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2008;1:14-21. "Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy"

- National Cancer Institute. What You Need to Know About Thyroid Cancer National Cancer Institute, 2010.Print

- Schmitt, Fernando. "Thyroid Cytology: Is FNA Still The Best Diagnostic Approach?"International Journal of Surgical Pathology, June 2010, vol 18, p.201-204.

- DeLellis R.A.; Lloyd R.V.; Heitz P.U.; et al., eds. (2004). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press. pp. 94–123. ISBN 978-92-832-2416-7.

- Cameselle-Teijeiro JM, Eloy C, Sobrinho-Simões M (2020). "Pitfalls in Challenging Thyroid Tumors: Emphasis on Differential Diagnosis and Ancillary Biomarkers". Endocr Pathol. 31 (3): 197–217. doi:10.1007/s12022-020-09638-x. PMC 7395918. PMID 32632840.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

"This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License"

External links

- Thyroid Cancer Clinical Trials Page of the American Thyroid Association

- Thyroid Cancer- National Cancer Institute

- Diagnostic patient information