Loose coupling

In computing and systems design, a loosely coupled system is one

- in which components are weakly associated (have breakable relationships) with each other, and thus changes in one component least affect existence or performance of another component.

- in which each of its components has, or makes use of, little or no knowledge of the definitions of other separate components. Subareas include the coupling of classes, interfaces, data, and services.[1] Loose coupling is the opposite of tight coupling.

Advantages and disadvantages

Components in a loosely coupled system can be replaced with alternative implementations that provide the same services. Components in a loosely coupled system are less constrained to the same platform, language, operating system, or build environment.

If systems are decoupled in time, it is difficult to also provide transactional integrity; additional coordination protocols are required. Data replication across different systems provides loose coupling (in availability), but creates issues in maintaining consistency (data synchronization).

In integration

Loose coupling in broader distributed system design is achieved by the use of transactions, queues provided by message-oriented middleware, and interoperability standards.[2]

Four types of autonomy, which promote loose coupling, are: reference autonomy, time autonomy, format autonomy, and platform autonomy.[3]

Loose coupling is an architectural principle and design goal in service-oriented architectures; eleven forms of loose coupling and their tight coupling counterparts are listed in:[4]

- physical connections via mediator,

- asynchronous communication style,

- simple common types only in data model,

- weak type system,

- data-centric and self-contained messages,

- distributed control of process logic,

- dynamic binding (of service consumers and providers),

- platform independence,

- business-level compensation rather than system-level transactions,

- deployment at different times,

- implicit upgrades in versioning.

Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) middleware was invented to achieve loose coupling in multiple dimensions;[5] however, overengineered and mispositioned ESBs can also have the contrary effect and create undesired tight coupling and a central architectural hotspot.

Event-driven architecture also aims at promoting loose coupling.[6]

Methods for decreasing coupling

Loose coupling of interfaces can be enhanced by publishing data in a standard format (such as XML or JSON).

Loose coupling between program components can be enhanced by using standard data types in parameters. Passing customized data types or objects requires both components to have knowledge of the custom data definition.

Loose coupling of services can be enhanced by reducing the information passed into a service to the key data. For example, a service that sends a letter is most reusable when just the customer identifier is passed and the customer address is obtained within the service. This decouples services because services do not need to be called in a specific order (e.g. GetCustomerAddress, SendLetter).

In programming

Coupling refers to the degree of direct knowledge that one component has of another. Loose coupling in computing is interpreted as encapsulation vs. non-encapsulation.

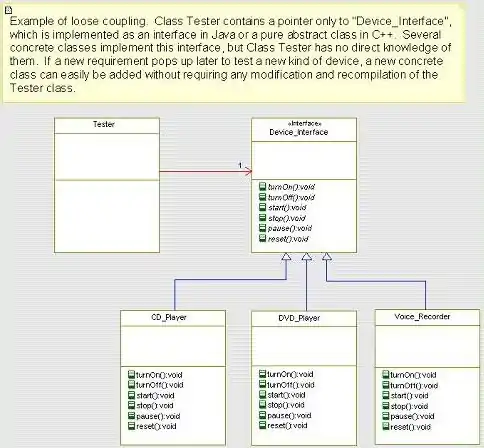

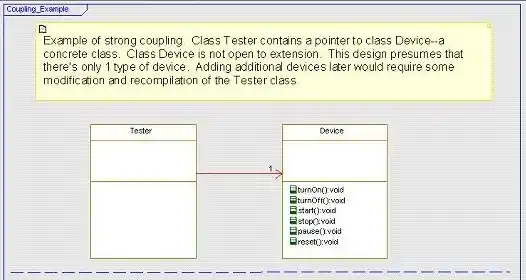

An example of tight coupling occurs when a dependent class contains a pointer directly to a concrete class which provides the required behavior. The dependency cannot be substituted, or its "signature" changed, without requiring a change to the dependent class. Loose coupling occurs when the dependent class contains a pointer only to an interface, which can then be implemented by one or many concrete classes. This is known as dependency inversion. The dependent class's dependency is to a "contract" specified by the interface; a defined list of methods and/or properties that implementing classes must provide. Any class that implements the interface can thus satisfy the dependency of a dependent class without having to change the class. This allows for extensibility in software design; a new class implementing an interface can be written to replace a current dependency in some or all situations, without requiring a change to the dependent class; the new and old classes can be interchanged freely. Strong coupling does not allow this.

This is a UML diagram illustrating an example of loose coupling between a dependent class and a set of concrete classes, which provide the required behavior:

For comparison, this diagram illustrates the alternative design with strong coupling between the dependent class and a provider:

Other forms

Computer programming languages having notions of either functions as the core module (see Functional programming) or functions as objects provide excellent examples of loosely coupled programming. Functional languages have patterns of Continuations, Closure, or generators. See Clojure and Lisp as examples of function programming languages. Object-oriented languages like Smalltalk and Ruby have code blocks, whereas Eiffel has agents. The basic idea is to objectify (encapsulate as an object) a function independent of any other enclosing concept (e.g. decoupling an object function from any direct knowledge of the enclosing object). See First-class function for further insight into functions as objects, which qualifies as one form of first-class function.

So, for example, in an object-oriented language, when a function of an object is referenced as an object (freeing it from having any knowledge of its enclosing host object) the new function object can be passed, stored, and called at a later time. Recipient objects (to whom these functional objects are given) can safely execute (call) the contained function at their own convenience without any direct knowledge of the enclosing host object. In this way, a program can execute chains or groups of functional objects, while safely decoupled from having any direct reference to the enclosing host object.

Phone numbers are an excellent analog and can easily illustrate the degree of this decoupling.

For example: Some entity provides another with a phone number to call to get a particular job done. When the number is called, the calling entity is effectively saying, "Please do this job for me." The decoupling or loose coupling is immediately apparent. The entity receiving the number to call may have no knowledge of where the number came from (e.g. a reference to the supplier of the number). On the other side, the caller is decoupled from specific knowledge of who they are calling, where they are, and knowing how the receiver of the call operates internally.

Carrying the example a step further, the caller might say to the receiver of the call, "Please do this job for me. Call me back at this number when you are finished." The 'number' being offered to the receiver is referred to as a "Call-back". Again, the loose coupling or decoupled nature of this functional object is apparent. The receiver of the call-back is unaware of what or who is being called. It only knows that it can make the call and decides for itself when to call. In reality, the call-back may not even be to the one who provided the call-back in the first place. This level of indirection is what makes function objects an excellent technology for achieving loosely coupled programs.

Communication between loosely coupled components may be based on a flora of mechanisms, like the mentioned asynchronous communication style or the synchronous message passing style [7]

Measuring data element coupling

The degree of the loose coupling can be measured by noting the number of changes in data elements that could occur in the sending or receiving systems and determining if the computers would still continue communicating correctly. These changes include items such as:

- Adding new data elements to messages

- Changing the order of data elements

- Changing the names of data elements

- Changing the structures of data elements

- Omitting data elements

See also

References

- Loosely Coupled: The Missing Pieces of Web Services by Doug Kaye

- Pautasso C., Wilde E., Why is the Web Loosely Coupled?, Proc. of WWW 2009

- F. Leymann Loose Coupling and Architectural Implications Archived 2016-10-02 at the Wayback Machine, ESOCC 2016 keynote

- N. Josuttis, SOA in Practice. O'Reilly, 2007, ISBN 978-0-596-52955-0.

- M. Keen et al, Patterns: Implementing an SOA using an Enterprise Service Bus, IBM, 2004

- How EDA extends SOA and why it is important Jack van Hoof

- Mielle, Grégoire. "Microservices patterns: synchronous vs asynchronous communication". Microservices patterns: synchronous vs asynchronous communication. greeeg. Retrieved 18 February 2022.