Timeline of women's suffrage in Arizona

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Arizona. The first women's suffrage bill was brought forward in the Arizona Territorial legislature in 1883, but it did not pass. Suffragists work to influence the Territorial Constitutional Convention in 1891 and lose the women's suffrage battle by only three votes. That year, the Arizona Suffrage Association is formed. In 1897, taxpaying women gain the right to vote in school board elections. Suffragists both from Arizona and around the country continue to lobby the territorial legislature and organize women's suffrage groups. In 1903, a women's suffrage bill passes, but is vetoed by the governor. In 1910, suffragists work to influence the Arizona State Constitutional Convention, but are also unsuccessful. When Arizona becomes a state on February 14, 1912, an attempt to legislate a women's suffrage amendment to the Arizona Constitution fails. Frances Munds mounts a successful ballot initiative campaign. On November 5, 1912, women's suffrage passes in Arizona. In 1913, the voter registration books are opened to women. In 1914, women participate in their first primary elections. Arizona ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 12, 1920. However, Native American women and Latinas would wait longer for full voting rights.

.jpg.webp)

19th century

1880s

1883

- Murat Masterson of Prescott introduces a partial women's suffrage bill for women to vote in school board elections, but it fails.[1]

1884

- The first Arizona chapter of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is formed.[2]

1887

1890s

1891

- Josephine Brawley Hughes and Laura M. Johns testify on women's suffrage at the Territorial Constitutional Convention.[4][5]

- Women's suffrage fails at the convention by 3 votes.[5]

- Hughes is part of the founding of the Arizona Suffrage Association.[6][4]

1895

1896

- January: Hughes attends the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) Convention in Washington, D.C.[7]

1897

- Johns addresses the territorial legislature on women's suffrage.[7]

- A bill is passed that allows women taxpayers to vote in school board elections.[8]

1899

- Carrie Chapman Catt visits Phoenix to advocate for women's suffrage.[9]

- A women's suffrage bill passes the lower house of the legislature.[10]

- The school board suffrage law is declared invalid by the Arizona Territorial Supreme Court.[8]

20th century

1900s

1901

- Lida P. Robinson works to promote a women's suffrage bill, but it does not pass.[11]

1902

- A women's suffrage convention is held in Phoenix.[12]

1903

- Governor Alexander Oswald Brodie vetoes the women's suffrage bill.[4][13]

1905

- The women's suffrage movement in Arizona stalls, even as NAWSA sends field worker, Mary C. C. Bradford, to revive interest.[13]

1909

- Laura Clay and Frances Munds lobby the territorial legislature on women's suffrage, but the suffrage bill does not pass.[14][13]

- The territorial legislature passes a literacy test law, which is supported by the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association.[15]

1910s

1910

- Laura Gregg from NAWSA is sent to Arizona to continue organizing suffrage groups around the state.[16]

- October 10: The Arizona Constitutional Convention meets.[16]

- Suffragists lobby the delegates for women's suffrage to be added to the constitution, but are unsuccessful.[17]

1912

- February 14: Arizona becomes a state.[18]

- A women's suffrage amendment bill fails in the Arizona State Legislature by one vote.[19]

- Munds starts a petition campaign to get women's suffrage on the November ballot.[19]

- July 5: Munds gets more than 4,000 signatures, enough to get the women's suffrage initiative on the ballot.[20]

- October: Suffragists have a women's suffrage booth at the Arizona State Fair.[21]

- November 5: Women's equal suffrage becomes part of the Constitution of Arizona.[22]

- Another literacy test law is passed, reducing the number of Mexican American voters.[15]

1913

- January: The Arizona State Legislature hold an emergency session and passes a bill opening the voter registration books to women.[23]

- March 15: Women in Arizona are allowed to register to vote for all elections.[22]

- May: NAWSA holds a celebratory parade in New York City for Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon granting women's suffrage.[23] Madge Udall represents Arizona.[23]

1914

- Women participate in the Arizona primary elections.[24]

- Congressional Union organizers, Josephine Casey and Jane Pincus, come to Arizona.[25]

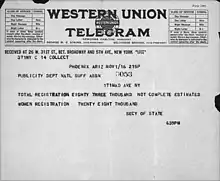

Telegram to NAWSA from Sidney P. Osborn November 1, 1916

Telegram to NAWSA from Sidney P. Osborn November 1, 1916

1916

- April 20: The Suffrage Special stops briefly in Maricopa and then arrives in Tucson.[26][27]

- April 21: The Suffrage Special arrives in Phoenix.[28]

1920s

1920

- February 12: Special legislative session convened to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.[29] It is ratified the same day.[30]

1924

- Native Americans gain United States Citizenship.[29]

1940s

1948

- The ban on Native Americans voting in Arizona is overturned by the Arizona Supreme Court.[31]

See also

- List of Arizona suffragists

- Women's suffrage in Arizona

- Women's suffrage in states of the United States

- Women's suffrage in the United States

References

- Osselaer 2009, p. 1.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 8.

- De Haan 2004, p. 378.

- Cleere, Jan (14 March 2015). "Western Women: Meet crusader Elizabeth Josephine Brawley Hughes". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- Anthony 1902, p. 470.

- "Voting Rights Timeline". Arizona State Library. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- Anthony 1902, p. 471.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 15.

- "A Voice for Giving Women a Voice". Arizona Capitol Times. 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- Harper 1922, p. 10.

- Hu, Joanna. "Biographical Sketch of Lida P. Robinson". Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890-1920 – via Alexander Street.

- Harper 1922, p. 10-11.

- Harper 1922, p. 11.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 24.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 36.

- Harper 1922, p. 12.

- Harper 1922, p. 13.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 42.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 43.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 44.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 45.

- "Arizona Suffrage". Window On Your Past. Retrieved 2020-12-13.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 54.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 52.

- Osselaer 2009, p. 62.

- "Suffragists Ready for Eastern Party". Arizona Daily Star. 1916-04-16. p. 16. Retrieved 2020-12-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Irwin 1921, p. 153.

- "Dr. Williams Will Preside". Arizona Republic. 1916-04-18. p. 7. Retrieved 2020-12-12 – via Newspapers.com.

- Eckstein, Susanna; Jones, Katie (30 June 2020). "How Arizona women won the vote". Arizona PBS. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- "Arizona and the 19th Amendment". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- "Native Vote Arizona". Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

Sources

- Anthony, Susan B. (1902). Anthony, Susan B.; Harper, Ida Husted (eds.). The History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 4. Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press.

- De Haan, Amy (Winter 2004). "Arizona Women Argue for the Vote: The 1912 Initiative Campaign for Women's Suffrage". Journal of Arizona History. 45 (4): 375–394. JSTOR 41690306 – via JSTOR.

- Harper, Ida Husted (1922). The History of Woman Suffrage. New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company.

- Irwin, Inez Haynes (1921). The Story of the Woman's Party. Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc. – via Internet Archive.

- Osselaer, Heidi J. (2009). Winning Their Place: Arizona Women in Politics, 1883-1950. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816534722 – via Project MUSE.