Timeline of women's suffrage in Missouri

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Missouri. Women's suffrage in Missouri started in earnest after the Civil War. In 1867, one of the first women's suffrage groups in the U.S. was formed, called the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri. Suffragists in Missouri held conventions, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly and challenged the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). The case that went to SCOTUS in 1874, Minor v. Happersett was not ruled in the suffragists' favor. Instead of challenging the courts for suffrage, Missouri suffragists continued to lobby for changes in legislation. In April 1919, they gained the right to vote in presidential elections. On July 3, 1919, Missouri becomes the eleventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

19th century

1860s

1866

- December: Senator B. Gratz Brown of Missouri states publicly that he is for universal suffrage for anyone, regardless of "race, color, or sex."[1]

- Women petition the Missouri General Assembly to remove the word "male" from the description of a voter in the state constitution.[2]

1867

- May: The Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri (WSAM) is formed.[3][4]

- October: A women's rights convention is held in St. Louis with large attendance numbers.[5]

1868

- The Hannibal Courier comes out in favor of women's suffrage.[6]

1869

- February: Members of WSAM petition the Missouri General Assembly for women's suffrage.[7]

- October: Missouri Woman Suffrage Convention is held in St. Louis.[8]

- October: Virginia Minor gives a speech at the convention, introducing the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment already gives women the right to vote.[9]

1870s

1870

- May: The St. Louis County Woman Suffrage Association is formed.[10]

- November: Delegates are chosen to attend the annual American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in Cleveland.[11]

- The St. Louis County Woman Suffrage Association sends a "memorial" to the United States Congress to amend the U.S. Constitution to support women's suffrage.[12]

1871

- Women meet with politicians, including Governor B. Gratz Brown, when the Missouri General Assembly comes back into session.[13]

- WSAM becomes affiliated with the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).[4]

1872

- October 15: Virginia Minor attempts to register to vote and is denied based on her gender.[9]

- November: AWSA holds its third annual convention in St. Louis.[14]

1873

- January 2: Virginia Minor and her husband, Francis Minor, petition the courts for the right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment.[15]

- February 3: The Minor case is heard in the Old Courthouse and lost. They appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court.[15]

- May 7: The Minor case is heard at the Missouri Supreme Court. The court decides that the Fourteenth Amendment only applies to newly freed slaves. The Minors appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS).[15]

1875

- In Minor v. Happersett, SCOTUS rules that the United States Constitution does not confer suffrage and until new laws were written, women would not vote in the United States.[15][9][16]

- Women attempted to get a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage in the state constitutional convention, but failed.[12]

1876

- Phoebe Couzins lectures on women's suffrage.[17]

1879

- Virginia Minor becomes the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) of Missouri.[7]

- May: NWSA holds their annual convention in St. Louis.[18]

1880s

1881

- Women petition the Missouri General Assembly for a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage.[19]

1883

- Women petition the Missouri General Assembly for "general and presidential suffrage for women."[19]

1889

- January 24: Virginia Minor speaks to the United States Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage.[20]

1890s

1892

- Women's suffrage convention featuring women from around the United States is held in Kansas City.[21]

- The Kansas City Equal Suffrage League was formed in 1892 with Kersey Coates as president.[22]

1894

- August 14: Virginia Minor dies and leaves $1,000 to Susan B. Anthony for suffrage work.[7]

1895

- The Missouri Equal Suffrage Association (MESA) is formed.[23]

1896

- June: MESA holds a convention in St. Louis to take place at the same time as the Republican National Convention.[24]

- A state suffrage convention is held in Kansas City.[25]

1897

- Delegates to the Missouri General Assembly request a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage.[25]

- January: Mary C. C. Bradford goes on a three week lecture tour in Missouri.[26]

- December: A state suffrage convention is held in Bethany.[27]

1898

- The state suffrage convention meets in St. Joseph.[27] Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt are present.[28]

1899

- The state suffrage convention is held in Chilicothe.[27]

20th century

1900s

- The state suffrage convention is held in St. Joseph.[27]

1901

- The state suffrage convention is held in St. Louis.[27]

1910s

1911

- February 4: The Kansas City Woman Suffrage Association is formed.[29]

- February 14: Several large women's suffrage organizations in Missouri merge into the Missouri Equal Suffrage Association (MESA).[30]

1912

- September: State suffrage convention is held in Sedalia.[31]

- November 30: Suffragists in Joplin, Missouri organize and affiliate with the Women's Equal Suffrage League.[32]

1913

- March 3: The all-women marching band, Maryville Ladies Marching Band, plays at the NAWSA Women's National Suffrage Rally in Washington, D.C.[33][34]

- September 30: Women's suffrage car parade held in St. Louis.[35]

1914

- May 2: Rally held in St. Louis And Carthage, Missouri on National Suffrage Day.[35][36]

- Spring: The St. Louis Times publishes a "special suffrage edition."[37]

- The Columbia Equal Suffrage League canvasses house-to-house to promote women's suffrage and record the number of people supporting women's suffrage.[3]

- Emily Newell Blair becomes the first editor of the first suffrage journal in the state, Missouri Woman.[38]

1915

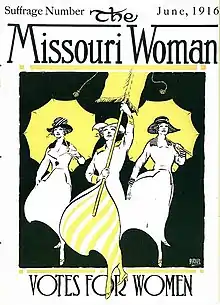

- Suffrage magazine, The Missouri Woman, is first published.[39]

1916

- Suffragists lobby the Missouri General Assembly for a Presidential Suffrage bill.[40]

- February: Emily Newell Blair meets with suffrage leaders in Missouri to work out new strategies for protest.[41]

- April 12: The Suffrage Special stops in Kansas City, Missouri.[42]

- April: Mary Semple Scott becomes the editor of The Missouri Woman.[43]

- May 14: The Suffrage Special meets at the Scottish Rite Cathedral in St. Joseph, Missouri.[42]

- June: During the Democratic National Convention, 3,000 suffragists staged a motionless parade on Locust Street in St. Louis. The event was called the "Golden Lane."[2][3]

- June: During the Republican National Convention, suffragists sent telegrams to the Missouri electors and urged them to support women's suffrage.[44]

1917

- February: Suffragists petition the Missouri General Assembly for limited suffrage.[45]

- May: The state women's suffrage convention took place in Kansas City.[46]

1919

- Helen Guthrie Miller speaks to the Missouri Democratic Convention on women's suffrage, becoming the first women to speak to a Missouri political party.[47]

- January 8: State Representative Walter E. Bailey of Joplin proposes a presidential suffrage bill in the Missouri General Assembly called "Bill One."[48]

- March: The Missouri General Assembly passes the Presidential Suffrage Bill.[3]

- March: NAWSA holds their Golden Jubilee Convention in St. Louis.[3][49]

- April 5: Governor Frederick D. Gardner signs the Presidential Suffrage Bill.[50]

- July 3: Missouri becomes the 11th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.[3]

- October: The Missouri League of Women Voters is formed.[51]

- October: The Missouri Woman is merged with the Woman Citizen.[52]

- November 13: MESA becomes the League of Women Voters of St. Louis.[53]

See also

References

- Morris 1930, p. 68.

- Cooperman, Jeannette (2020-04-28). "St. Louis suffragists played a key role in advocating for the 19th Amendment 100 years ago". St. Louis Magazine. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Missouri Women: Suffrage to Statecraft". University of Missouri. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri Formed". St. Louis Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Fordyce 1920, p. 290.

- "Woman Suffrage". Daily Missouri Republican. 1868-07-24. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-09-24 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Virginia Minor -". Archives of Women's Political Communication. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- "Virginia Minor". Historic Missourians - The State Historical Society of Missouri. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Anderson, Caiti (2016-04-22). "Minor v. Happersett: The Supreme Court and Women's Suffrage". State of Elections. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Woman Suffrage Call". The Missouri Republican. 1870-05-27. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-09-24 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Woman Suffrage Association". The Missouri Republican. 1870-11-09. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-09-24 – via Newspapers.com.

- Morris 1930, p. 82.

- Morris 1930, p. 71.

- O'Neil, Tim (19 November 2011). "A Look Back • Suffragists meet in St. Louis in 1872". STLtoday.com. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Virginia Minor and Women's Right to Vote - Gateway Arch National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". NPS. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- "Legal Case of Minor v. Happersett". History of U.S. Woman's Suffrage. Retrieved 2020-09-27.

- Davidson, Clarissa Start (1972). "Women's Role in Missouri History, 1821-1971". Missouri Almanac, 1971-1972. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Morris 1930, p. 73.

- Morris 1930, p. 74.

- "Statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage - Jan. 24, 1889". Archives of Women's Political Communication. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Anthony 1902, p. 790.

- McBride 1920, p. 320.

- Morris 1930, p. 76.

- Morris 1930, p. 77.

- Morris 1930, p. 78.

- Anthony 1902, p. 791.

- Morris 1930, p. 79.

- Anthony 1902, p. 792.

- McBride 1920, p. 321.

- Van Es 2014, p. 28.

- Atkinson 1920, p. 303.

- Van Es 2014, p. 55-56.

- Van Es 2014, p. 28-29.

- "Alma Nash & Her Band". Missouri Women. 2010-11-16. Retrieved 2020-09-21.

- Van Es 2014, p. 29.

- Van Es 2014, p. 56.

- Scott 1920, p. 372.

- Driscoll, Carol (July 2020). "Emily Newell Blair: Missouri's Suffragette". Missouri Life. 47 (5): 40–43 – via EBSCOhost.

- Scott 1920, p. 373.

- Leighty 1920, p. 347.

- Van Es 2014, p. 30.

- "Suffrage Special Will Stop". The Wichita Daily Eagle. 1916-04-04. p. 9. Retrieved 2020-01-20 – via Newspapers.com.

- Scott 1920, p. 374.

- Passmore 1920, p. 368.

- Passmore 1920, p. 369.

- Leighty 1920, p. 349.

- O'Connor, Candace (1994). "Women Who Led the Way". Missouri Almanac, 1993-94. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Van Es 2014, p. 31.

- "National American Women Suffrage, St. Louis, 3-25-19". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Van Es 2014, p. 33.

- "History of the Missouri LWV". 2012-04-14. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- Scott 1920, p. 377.

- "Founded November 13, 1919". MyLO. 2020-02-06. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

Sources

- Anthony, Susan B. (1902). Anthony, Susan B.; Harper, Ida Husted (eds.). The History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 4. Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press.

- Atkinson, Florence (1920). "'Middle Ages' of Equal Suffrage in Missouri". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 299–306.

- Fordyce, Christine Orrick (1920). "Early Beginnings". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 288–299.

- Leighty, Agnes I. (1920). "Suffrage in Missouri for the Years 1916-1917". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 343–349.

- McBride, Mrs. Thomas (1920). "The Part of the Kansas City Equal Suffrage League in the Campaign for Equal Suffrage". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 320–327.

- Morris, Monia Cook (October 1930). "The History of Woman Suffrage in Missouri, 1867-1901". Missouri Historical Review. 25 (1): 67–82.

- Passmore, Bertha K. (1920). "Congressional Work". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 367–372.

- Scott, Mary Semple (1920). "The Missouri Woman". The Missouri Historical Review. 14 (3–4): 372–377.

- Van Es, Mark A. (April 2014). Peculiar History of Women's Suffrage in Jasper County, Missouri (Master of Arts thesis). Pittsburg State University.