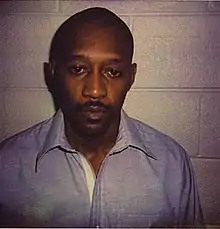

Timothy Wilson Spencer

Timothy Wilson Spencer (March 17, 1962 – April 27, 1994), also known as The Southside Strangler, was an American serial killer who committed three rapes and murders in Richmond, Virginia, and one in Arlington, Virginia, in the fall of 1987.[1] In addition, he is believed to have committed at least one previous murder, in 1984, for which a different man, David Vasquez, was wrongfully convicted.[1] He was known to police as a prolific home burglar.

Timothy Wilson Spencer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 17, 1962 Green Valley, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | April 27, 1994 (aged 32) |

| Cause of death | Execution by electrocution |

| Other names | The Southside Strangler The Southside Slayer The Southside Rapist The Masked Rapist |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Conviction(s) | Capital murder (3 counts) Rape Burglary Robbery |

| Criminal penalty | Death by electrocution |

| Details | |

| Victims | 5 |

Span of crimes | 1984–1988 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Virginia |

Date apprehended | January 20, 1988 |

Spencer became the first serial killer in the United States to be convicted on the basis of DNA evidence,[2] with David Vasquez being the first to be exonerated following conviction on the basis of exculpatory DNA evidence.

Crimes

Debbie Dudley Davis, a 35-year-old account executive, was murdered between 9:00 p.m. on September 18, 1987, and 9:30 a.m. on September 19, 1987, in her Westover Hills apartment. Richmond Police discovered her naked body lying on the bed. She had been strangled with a ligature and ratchet-type device.[3]

Dr. Susan Hellams was murdered in her West 31st St. home on the night of October 2, 1987, or the early morning of October 3, 1987. The police were called by her husband after he returned home and discovered her partially clothed body on the floor of the couple's bedroom closet. Hellams was a resident in neurosurgery at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond. Her attacker apparently gained access to the house by cutting out a large portion of a second-story bedroom window screen. The medical examiner determined that the cause of Hellams' death was ligature strangulation, believed to have been caused by two belts found around her neck.[4]

On November 22, 1987, Diane Cho, a 15-year-old high school student, was found in her family's apartment located on Gavilan Court in Chesterfield County, near Richmond. She too was raped and strangled in circumstances similar to the Davis and Hellams murders.[1]

Spencer's final known victim, Susan Tucker, 44, is believed to have been raped and murdered in her condominium in Arlington, Virginia on or about November 27, 1987. Her body was not found until December 1, 1987. Her injuries left detectives certain that her death was caused by the murderer now dubbed by the press as the "Southside Strangler".[1]

Investigation

On January 20, 1988, Arlington County police arrested Timothy Wilson Spencer, a 25-year-old Richmond resident, for the rape and murder of Susan Tucker in her Arlington home. Police established that Spencer had traveled from Richmond to Arlington during the period of her death to spend Thanksgiving with his mother, who lived about a mile from Tucker's home.

He was charged with the murders of Debbie Davis, Susan Hellams, and Diane Cho. At the times of the Richmond murders, Spencer had been staying at a South Richmond parolees' halfway house within walking distance of both Davis's and Hellams' residence. Before his release, he had been serving a sentence for a 1984 burglary conviction, which explains the hiatus between crimes.

Forensic testing commenced on samples found at the crime scenes as the cases were prepared for trial.

Trials, appeals, and execution

Spencer first came to trial in Arlington, Virginia, on July 11, 1988, for the rape, burglary and murder of Susan Tucker. He was represented by Carl Womack and Thomas Kelley. Spencer was convicted and sentenced to death, following the presentation of DNA evidence linking him to the Tucker crime scene, the first case in Virginia in which DNA was successfully used to prove an offender's identity.[5]

Following his conviction for the Tucker murder, Spencer again went on trial, this time in Richmond, for the rape, burglary and murder of Debbie Davis. DNA evidence in the form of semen and hairs collected at the scene of Debbie Davis' murder was determined to be consistent with Spencer's DNA. Forensic evidence given at his trial indicated that the statistical likelihood that the DNA found at the crime scene came from someone other than Spencer was one in 705,000,000. Spencer was convicted of the rape, burglary and capital murder of Debbie Davis on September 22, 1988.[3]

Spencer came to trial, again in Richmond, for the rape, burglary, and murder of Susan Hellams on January 17, 1989. He was convicted and again sentenced to death after DNA evidence linking him to the scene of Hellams' murder was used by the prosecuting attorneys.[6]

Following the successful conviction of Spencer for the Tucker, Davis, and Hellams murders, his DNA was compared with samples collected at other crime scenes, including both open and apparently closed cases. As a result of these investigations, it was determined that DNA evidence linked him to the 1984 murder of Carolyn Hamm, a crime for which David Vasquez had been convicted in early 1985. While the standard of the DNA evidence was determined to be inconclusive, FBI investigators were sufficiently confident given the factual similarities to the more recent crimes to report the conclusion that Spencer most likely was responsible for the Hamm murder and others. Vasquez was granted an unconditional pardon for her murder on January 4, 1989, having served five years of a 35-year prison sentence, and became the first American to be exonerated on the basis of exculpatory DNA evidence.[7]

Despite the conclusions of investigators as to his guilt, Spencer was never charged or convicted for Carolyn Hamm's murder.[7] DNA evidence was not conclusive in Diane Cho's case; nevertheless, Spencer was tried and convicted for her murder.[8]

Spencer's motions to appeal his convictions for the murders of Susan Tucker, Debbie Davis, and Susan Hellams were denied.[9][10] The United States Court of Appeal affirmed in its judgment that the reliance on evidence based on new DNA technology in obtaining Spencer's conviction was sound.[11]

Timothy Wilson Spencer was executed on April 27, 1994, at Greensville Correctional Centre in Jarratt, Virginia. He was put to death in the electric chair.[12]He was pronounced dead at 11:13 p.m. EST. He declined to give a final statement before his execution.[13]

Aftermath

Paul Mones' book Stalking Justice: The Dramatic True Story of the Detective Who First Used DNA Testing to Catch a Serial Killer, published in July 1995, details the experience of Arlington Detective Joe Horgas in investigating the murders and pursuing the matter to the conviction of Spencer and the vindication of David Vasquez.[14]

The murders and Spencer's conviction also formed the basis for an episode of the forensic science documentary series Medical Detectives, which aired on October 31, 1996.[13]

The investigation of the Southside murders and eventual conviction of Timothy Spencer form the subject matter of Chapter 11 of former FBI psychological profiler John Douglas' 1996 memoir Journey into Darkness.[15]

Patricia Cornwell's bestselling novel Postmortem attracted considerable controversy and criticism in Richmond at the time of its publication in 1990 due to the close similarities between the facts of Spencer's 1987 crimes (particularly Hellams' case) and those of the serial murders which formed the basis for Cornwell's plot. Cornwell was in fact employed as a computer analyst within the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Richmond at the time of Spencer's 1987 killings.[16] While it is acknowledged that the subject matter of several of Cornwell's earlier books are loosely based on real crimes in the Virginia area, she has stated that she writes about specific types of crime, not specific cases.[16]: 84

In 2003, Discovery Channel tv show The New Detectives aired the episode "Random Targets", which detailed Spencer's crimes along with the case of serial killer Mark William Cunningham.

On January 26, 2020, Spencer's younger brother Travis talked about Spencer's crimes on Evil Lives Here in the episode "My Brother Made History." He also gave an interview in the British television program Born to Kill?, which made an episode about Spencer's crimes.

References

- Lane, Brian; Wilfred Gregg (1995). The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers. Berkley Books. pp. 324. ISBN 0-425-15213-8.

- Miller, Mitchell (April 28, 1994). "Serial Killer Convicted by DNA Evidence Executed". Associated Press. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- "Timothy W. Spencer, Petitioner-appellant, v. Edward W. Murray, Director, Respondent-appellee, 5 F.3d 758 (4th Cir. 1993)". Justia Law.

- "Timothy W. Spencer, Petitioner-appellant, v. Edward W. Murray, Director; Commonwealth of Virginia,respondents-appellees, 18 F.3d 229 (4th Cir. 1994)".

- "Timothy W. Spencer, Petitioner-appellant, v. Edward W. Murray, Director, Respondent-appellee, 18 F.3d 237 (4th Cir. 1994)".

- Spencer v. Murray, 18 F.3d 229, (4th Cir.1994)

- Newton, Michael; French, John L. (2007). The Encyclopedia of Crime Scene Investigation. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-4381-2983-9.

- CHESTERFIELD JURY CONVICTS SPENCER OF CHO MURDER

- http://cases.justia.com/us-court-of-appeals/F3/18/237/531097/ (Tucker)

- http://cases.justia.com/us-court-of-appeals/F3/5/758/626409/ (Davis)

- "First Conviction Based On DNA Use Is Upheld". The New York Times. September 24, 1989. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Murderer Put to Death In Virginia". The New York Times. April 28, 1994. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Southside Strangler". IMDb.

- Mones, Paul A. (1995). Stalking Justice. Pocket Books. ISBN 067170348X.

- Douglas, John E.; Olshaker, Mark (May 2010). Journey into Darkness. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1439199817.

- Beahm, George W. The Unofficial Patricia Cornwell Companion St. Martin's Minotaur, New York, 2002.

External links

- Murderous States Of Mind podcast – Episode #11: Timothy Spencer AKA The Southside Strangler https://msomindpod.buzzsprout.com/