Tiryns

Tiryns (/ˈtɪrɪnz/ or /ˈtaɪrɪnz/; Ancient Greek: Τίρυνς; Modern Greek: Τίρυνθα) is a Mycenaean archaeological site in Argolis in the Peloponnese, and the location from which the mythical hero Heracles was said to have performed his Twelve Labours. It lies 20 km (12 mi) south of Mycenae.

Τίρυνς Τίρυνθα | |

General view of the Citadel of Tiryns, with Cyclopean masonry | |

Shown within Greece | |

| Location | Argolis, Greece |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°35′58″N 22°48′00″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Ancient Greece |

| Official name | Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1999 (23rd session) |

| Reference no. | 941 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Tiryns was a hill fort with occupation ranging back seven thousand years, from before the beginning of the Bronze Age. It reached its height of importance between 1400 and 1200 BC, when it became one of the most important centers of the Mycenaean world, and in particular in Argolis. Its most notable features were its palace, its Cyclopean tunnels and especially its walls, which gave the city its Homeric epithet of "mighty walled Tiryns". Tiryns became associated with the myths surrounding Heracles, as the city was the residence of the hero during his labors, and some sources cite it as his birthplace.[1]

The famous megaron of the palace of Tiryns has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four Minoan-style wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. Two of the three walls of the megaron were incorporated into an archaic temple of Hera. The site went into decline at the end of the Mycenaean period, and was completely deserted by the time Pausanias visited in the 2nd century AD.

In 1300 BC the citadel and lower town had a population of 10,000 people covering 20–25 hectares. Despite the destruction of the palace in 1200 BC, the city population continued to increase and by 1150 BC it had a population of 15,000 people.[2][3][4]

Along with the nearby ruins of Mycenae, UNESCO designated Tiryns as a World Heritage Site in 1999 because of its outstanding architecture and testimony to the development of Ancient Greek civilization.[5]

Legend

Tiryns is first referenced by Homer, who praised its massive walls.[6] Ancient tradition held that the walls were built by the Cyclopes because only giants of superhuman strength could have lifted the enormous stones.[7] After viewing the walls of the ruined citadel in the 2nd century AD, the geographer Pausanias wrote that two mules pulling together could not move even the smaller stones.[8]

Tradition also associates the walls with Proetus, the sibling of Acrisius, king of Argos. According to the legend Proetus, pursued by his brother, fled to Lycia. With the help of the Lycians, he managed to return to Argolis. There, Proetus occupied Tiryns and fortified it with the assistance of the cyclopes. Thus Greek legend links the three Argolic centers with three mythical heroes: Acrisius, founder of the Doric colony of Argos; his brother Proetus, founder of Tiryns; and his grandson Perseus, the founder of Mycenae. But this tradition was born at the beginning of the historical period, when Argos was fighting to become the hegemonic power in the area and needed a glorious past to compete with the other two cities.

History

Neolithic

The area has been inhabited since prehistoric times. A small neolithic settlement thrived.

Early Helladic

In the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, it was a flourishing early pre-Hellenic settlement located about 15 km southeast of Mycenae, on a hill 300 m long, 45–100 m wide, and no more than 18 meters high. From this period survived under the yard of a Mycenaean palace, an imposing circular structure 28 meters in diameter, which appears to be a fortified place of refuge for the city's inhabitants in time of war, and/or a residence of a king. Its base was powerful, and was constructed from two concentric stone walls, among which there were others cross-cutting, so that the thickness reached 45 m. The superstructure was clay and the roof was made from fire-baked tiles.

Middle Helladic

The first Greek inhabitants—the creators of the Middle Helladic civilization and the Mycenaean civilization after that—settled Tiryns at the beginning of the Middle Helladic period (2000–1600 BC).

Late Helladic

In the Late Helladic, the city underwent its greatest growth, also known as the Mycenaean period. The Acropolis was constructed in three phases, the first at the end of the Late Helladic II period (1500–1400 BC), the second in Late Helladic III (1400–1300 BC), and the third at the end of the Late Helladic III B (1300–1200 BC). The surviving ruins of the Mycenaean citadel date to the end of the third period.[9] The city proper surrounded the acropolis on the plain below.

The disaster that struck the Mycenaean centers at the end of the Bronze Age affected Tiryns, but it is certain that the area of the palace was inhabited continuously into the early Archaic period, until the middle of the 8th century BC (a little later a temple was built in the ruins of the palace). In the post-palatial LH IIIC period (c. 1180 BC), an extensive deposit of precious items, including gold and silver objects and a fifteenth-century BC Minoan signet ring, was made in a cauldron in Tiryns's lower town, within the foundations of a Mycenaean house.[10]: 129

Classical period

At the beginning of the Classical period Tiryns, like Mycenae, became a relatively insignificant city. When Cleomenes I of Sparta defeated the Argives, their slaves occupied Tiryns for many years, according to Herodotus.[11] Herodotus also mentions that Tiryns took part in the Battle of Plataea in 480 BC with 400 hoplites.[12] Even in decline, Mycenae and Tiryns were disturbing to the Argives, who in their political propaganda wanted to monopolize the glory of legendary (and mythical) ancestors. In 468 BC Argos completely destroyed both Mycenae and Tiryns, and—according to Pausanias—transferred the residents to Argos, to increase the population of the city. However, Strabo says that many Tirynthians moved to found the city of Halieis, modern Porto Heli.[13][14]

Despite its importance, little value was given to Tiryns and its mythical rulers and traditions by epics and drama. Pausanias dedicated a short piece (2.25.8) to Tiryns, and newer travelers, traveling to Greece in search of places where the heroes of the ancient texts lived, did not understand the significance of the city.

Excavations

The Acropolis was first excavated by Alexandros Rizos Rangavis and the German scholar Friedrich Thiersch in 1831.[15] After trial excavations in August 1876, Heinrich Schliemann considered the palace of Tiryns to be medieval, so he came very close to destroying the remains to excavate deeper for Mycenaean treasures. He returned in 1884 with more archaeological experience and worked for 5 months there.[16] However, the next period of excavation was under Wilhelm Dörpfeld, a director of the German Archaeological Institute; this time, the ruins were estimated properly.[17][18]

The excavations were repeated later by Dörpfeld with the cooperation of other German archaeologists, who continued his work until 1938. From 1910, the excavations were led by Georg Karo,[19]: 639 though the "Tiryns Treasure" was initially excavated in 1915 in Karo's absence by the Greek archaeologist Apostolos Arvanitopoulos, who was stationed in the region as a reserve officer of the Hellenic Army.[10]: 129 Karo was removed from his post at the DAI in late 1916, and excavations at Tiryns thereafter ceased until the end of the First World War in 1918.[20]: 261 After World War II (1939–1945), the work was continued by the Institute and the Greek Archaeological Service. In particular there were excavations in 1977, 1978/1979, and again in 1982/83.[21][22][23]

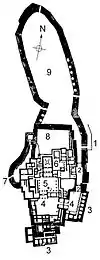

Archaeological site

The walls extend to the entire area of the top of the hill. Their bases survive throughout all of their length, and their height in some places reaching 7 meters, slightly below the original height, which is estimated at 9–10 m. The walls are quite thick, usually 6 meters, and up to 17 m at the points where the tunnels pass through. A strong transverse wall separates the acropolis into two sections -the south includes the palatial buildings, while the northern protects only the top of the hill area. In this second section, which dates to the end of the Mycenaean era, small gates and many tunnels occasionally open, covered with a triangular roof, which served as a refuge for the inhabitants of the lower city in times of danger.[24]

The entrance of the citadel was always on the east side, but had a different position and form in each of the three construction phases. In the second phase the gate had the form of the Lion Gate of Mycenae. Left there was a tower and to the right was the arm of the wall, so the gate was well protected, since the attackers were forced to cross a very narrow corridor, while the defense could hit them from above and from both sides. In the third phase the gate was moved further out. The palace of the king, inside the citadel, similar to that of Mycenae (dimensions 11.8 × 9.8 m) consists of three areas: the outer portico with the two columns, the prodomos (anteroom) and the domos (main room) with the cyclical fireplace that was surrounded by four wooden columns. The lateral compartments of the palace seem to have a second floor.

The decoration of the walls of the outer arcade was rich. They had a zone at the bottom of alabaster slabs with relief rosettes and flowers. The rest was decorated with frescos. Three doors lead to prodomos and then another to the domos. In the middle of the eastern wall is visible in the floor the place that corresponded to the royal throne. The floor was richly decorated with different themes in the area around the walls and the space between the columns of the fireplace. Of course, here the walls were decorated with paintings.

In the ruins of the mansion, which burned during the 8th century BC, a Doric temple was built during the Geometric period. Smaller than the mansion, it consisted of two parts, the prodomos and the cella. The width of the temple was just greater than half that of the mansion, while the back wall of the temple reached the height of the rear columns of the fireplace. Three springs fed into the compound, one in the western side of the large courtyard which could be accessed by a secret entrance, and two at the end of north side of the wall, accessed via two tunnels in the wall. These and similar such structures found in other shelters are witnesses to the care which was taken here, as in other Mycenaean acropolises, to the basic problem of water access in a time of siege.

References

- "Tiryns, Greek Mythology Link". Archived from the original on 2002-08-07. Retrieved 2002-08-07.

- Yasur-Landau, Assaf (16 June 2014). The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139485876 – via Google Books.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns".

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; Boda, Sharon La (1 January 1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781884964022 – via Google Books.

- "Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns". UNESCO World Heritage Convention. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- Homer Iliad 2.555

- Pausanias Description of Greece - about Boeotia 9.36.5

- Pausanias Description of Greece - about Corinth 2.25.8

- Davis, Brent, Maran, Joseph and Wirghová, Soňa. "A new Cypro-Minoan inscription from Tiryns: TIRY Avas 002" Kadmos, vol. 53, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 91-109

- Maran, Joseph (2006). "Coming to Terms with the Past: Ideology and Power in Late Helladic IIIC". In Deger-Jalkotzy, Sigrid; Lemos, Irene S. (eds.). Ancient Greece: From the Mycenaean Palaces to the Age of Homer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 123–150. ISBN 978-0-7486-1889-7.

- Herodotus Book 6, 83

- Herodotus Book 9, 28

- Strabo 8, 373

- "A Brief History of Halieis". Geocities. Archived from the original on 2009-10-21. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- F. Thiersch, "Thiersch's Leben", Leipzig, 1866

- Heinrich Schliemann et. al., "Tiryns: The prehistoric palace of the kings of Tiryns, the results of the latest excavations", Charles Scribner's Sons, London, 1885

- Jebb, Richard Claverhouse. "The Homeric House, in relation to the Remains at Tiryns." The Journal of Hellenic Studies 7 (1886): 170-188

- Middleton, J. Henry. "A Suggested Restoration of the Great Hall in the Palace of Tiryns." The Journal of Hellenic Studies 7 (1886): 161-169

- Matz, Friedrich (September 1964). "Georg Karo". Gnomon. 36 (6): 637–640. JSTOR 27683484.

- Marchand, Suzanne (2008) [1996]. "Kultur and the World War". In Murray, Tim; Evans, Christopher (eds.). Histories of Archaeology: A Reader in the History of Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 238–278. ISBN 978-0-19-955008-1.

- Kilian, K. 1979. Ausgrabungen in Tiryns 1977: Bericht zu den Grabungen, Archäologischer Anzeiger 1979, 379–411

- Kilian, K. 1981. Ausgrabungen in Tiryns 1978/1979: Bericht zu den Grabungen, Archäologischer Anzeiger 1981, 149–194

- Kilian, K. 1988. Ausgrabungen in Tiryns 1982/83: Bericht zu den Grabungen, Archäologischer Anzeiger 1988, 105–151

- Zangger, Eberhard. "Landscape changes around Tiryns during the Bronze Age." American Journal of Archaeology 98.2 (1994): 189-212

Further reading

- Middleton, John Henry; Gardner, Ernest Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1013–1014.