Telmatobius culeus

Telmatobius culeus, commonly known as the Titicaca water frog or Lake Titicaca frog,[1] is a medium-large to very large and endangered species of frog in the family Telmatobiidae.[3] It is entirely aquatic and only found in the Lake Titicaca basin, including rivers that flow into it and smaller connected lakes like Arapa, Lagunillas and Saracocha, in the Andean highlands of Bolivia and Peru.[4][6] In reference to its excessive amounts of skin, it has jokingly been referred to as the Titicaca scrotum (water) frog.[7]

| Telmatobius culeus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Individual from the captive breeding program at Prague Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Telmatobiidae |

| Genus: | Telmatobius |

| Species: | T. culeus |

| Binomial name | |

| Telmatobius culeus (Garman, 1876) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It is closely related to the more widespread and semiaquatic marbled water frog (T. marmoratus),[8][9] which also occurs in shallow, coastal parts of Lake Titicaca,[10] but lacks the excessive skin and it is generally smaller (although overlapping in size with some forms of the Titicaca water frog).

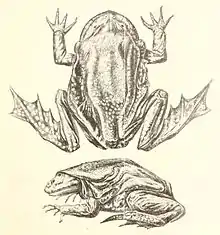

Appearance

Size

In the late 1960s, an expedition led by Jacques Cousteau reported Titicaca water frogs up to 60 cm (2 ft) in outstretched length and 1 kg (2.2 lb) in weight,[11][12][13] making these some of the largest exclusively aquatic frogs in the world (the exclusively aquatic Lake Junin frog can grow larger, as can the helmeted water toad and African goliath frog that sometimes can be seen on land).[14] The snout–to–vent length of the Titicaca water frog is up to 20 cm (8 in),[15][16] and the hindlegs about twice as long.[13]

Most individuals do not reach such sizes, but are still big frogs. Titicaca water frogs of the largest and typical form, upon which the species was first described, usually have a snout–to–vent length of 7.5 to 17 cm (3.0–6.7 in) and weigh less than 0.4 kg (0.9 lb).[14][16] This typical form tends to inhabit relatively deep water in eastern Lake Titicaca, but a minority of the individuals in the Coata River (which flows into far western Lake Titicaca) are similar.[6] Several other forms are found at shallower depths in Lake Titicaca, in smaller lakes that are part of the same basin, and in rivers and streams that flow into Titicaca. These tend to be smaller in size with a snout–to–vent length of 4 to 8.9 cm (1.6–3.5 in) and historically they were recognized as separate species (T. albiventris and T. crawfordi), but there are extensive individual variations (sometimes even at a single location), no clear limits between the forms (they intergrade) and taxonomic reviews have found that all are variants of the Titicaca water frog.[6] Females generally reach maturity at a slightly larger size than males, they average larger and they also have a larger maximum size than males.[16][17][18]

Morphology and color

In addition to total size, the various forms of the Titicaca water frog differ in the relative size of the dorsal shield (a hard structure on the back), relative width of the head and other morphological features, with most bays in Lake Titicaca having their own type.[6]

Compared to similar-sized frogs, the lungs of the Titicaca water frog only are about one-third the size. Instead it has excessive amounts of skin to help the frog respire in the cold water in which it lives.[4][19][20] The baggy skin is particularly distinct in large individuals.[21] In living individuals the skin folds are swollen with fluids, but if deflated the frog is actually relatively thin.[6]

The color is highly variable, but generally gray, brown or greenish above, and paler below. There are often some spots, which can form a marbled pattern.[18][21] Animals in coastal southernmost Lake Titicaca typically have striped thighs and relatively bright orange underparts.[6] If teased, Titicaca water frogs can secrete a sticky whitish fluid from their skin in defense.[22]

Habitat and ecology

Titicaca water frogs live exclusively in lakes and rivers in the Lake Titicaca basin.[6][21] Adults of the typical form generally live deeper than 10 m (33 ft) in Lake Titicaca itself, but the maximum limit is unknown.[23] While exploring this lake in a mini submarine, Jacques Cousteau filmed individuals and their prints in the bottom silt at 120 m (400 ft), which is the record depth for any species of frog.[13][21] The other forms of the Titicaca water frog are found at no more than 10 m (33 ft). A study that surveyed depths from the shore to 7 m (23 ft) near Isla del Sol found that adults were most common at 1.5–3 m (5–10 ft).[17] In general, Titicaca water frogs prefer a mixed bottom; either a muddy or sandy bottom with some rocks, or with plenty of aquatic plants and some rocks.[17][21]

Temperature

The Titicaca water frog spends its entire life in water that typically is 8–17.5 °C (46.5–63.5 °F), with the average annual temperature being near the middle and the minor seasonal variations being matched or even exceeded by the daily variations.[16][17] The frogs can regulate their own temperature by moving between different microhabitats with slightly different water temperatures and adults will sometimes position themselves on top of underwater rocks to bask in the sun that penetrate the lake's clear water.[17]

Respiration

The water in which it lives generally is very rich in oxygen, but limited by the low atmospheric pressure at the high altitude,[4][19][20] from about 3,800 m (12,500 ft) at Lake Titicaca to at least 4,250 m (14,000 ft) in associated river and smaller lakes.[6] It respires by its skin, which absorbs oxygen, functioning in a manner that is comparable to gills.[19][20][23] It sometimes performs "push-ups" or "bobs" up–and–down to allow more water to pass by its large skin folds. The skin is very rich in blood vessels that extend to its outermost layer. Of all frogs, it has the lowest relative red blood cell volume, but the highest count (i.e., many but small red blood cells) and with a high oxygen capacity. The frog mainly stays near the bottom and it has never been observed to surface in the wild, but captive studies indicate that it may surface to breathe using its diminutive lungs if the water is poorly oxygenated.[4][19][20]

Behavior

Social behavior and breeding

Although a good swimmer, several individuals can often be seen laying inactively next to each other on the bottom.[6] Titicaca water frogs tend to be most active during the night.[24]

The Titicaca water frog breeds year-round in shallow coastal water where the female lays about 80 to 500 eggs.[4][21] Amplexus lasts one to three days.[16] The "nest" site is typically guarded by the male until the eggs hatch into tadpoles,[21] which happens after about one to two weeks.[16][25] The tadpole stage lasts for a couple of months to a year.[21] The tadpoles and young froglets stay in shallows, only moving to deeper water when reaching adulthood.[17] Maturity is typically reached when about three years old.[16]

Feeding

The Titicaca water frog mostly feeds on amphipods (especially Hyalella) and snails (especially Heleobia and Biomphalaria),[17] but other food items are insects and tadpoles.[4] Adults also regularly eat fish (primarily Orestias, up to at least 10 cm [4 in] long) and cannibalism where large frogs eat small individuals has been recorded.[21][22][26] It has an extremely low metabolic rate; below that of all other frogs and among amphibians it is only higher than that of a few salamanders.[4][21][19]

In captivity, the tadpoles will feed on a range of tiny animals such as copepods, water fleas, small worms and aquatic insect larvae.[16]

Call and hearing

Similar to at least some other Telmatobius species, male Titicaca water frogs will call underwater when near the shore. The simple and repeated call can only be detected with a submerged microphone from a relatively short distance. The function is not clear, but calling primarily occurs during the night and it is likely related to attracting females, courtship or aggression.[27]

The ears are greatly reduced and several of the structures, including the tympanic membrane and the Eustachian tubes, are absent. How the Titicaca water frog hears is unconfirmed, but it probably involves the lungs (as known from some other frogs).[27]

Conservation status and threats

The Titicaca water frog has declined drastically, leading the IUCN to rank it as endangered.[1]

It was once common, with a survey in the late 1960s by Jacques Cousteau and colleagues counting 200 individuals in an only 1 acre (0.4 ha) plot of the huge lake.[13] Although not directly comparable, a survey in 2017 of three 100 m × 2 m (328 ft × 7 ft) transects at 38 locations only detected a total of 45 Titicaca water frogs at 6 of the locations (none at the remaining).[28] It is estimated that it declined by more than 80% in just 15 years, from 1990 to 2004, equalling three Titicaca water frog generations.[1][4][29] Several other species in the genus Telmatobius are facing similar risks.[3]

The causes of the precarious status of the Titicaca water frog are over-collecting for human consumption, pollution and introduced trout, and it may also be threatened by disease.[1][3]

Capture for food

The species is consumed as a traditional food or blended drink, and as traditional medicine that is claimed to be an aphrodisiac, and treat infertility, tuberculosis, anemia, asthma, osteoporosis and fever, but this is entirely unsupported by evidence.[30][31] Dishes with Titicaca water frogs are also sold by some local restaurants as a novelty to tourists.[29]

On a month-long expedition to Lake Titicaca 100 years ago, this frog was not seen in any of the markets in the region, no locals were seen hunting for it and when asked locals said they considered it inedible.[22] Whether this reporting was incomplete or there has been a significant change is unclear, but by the 2000s tens of thousands were caught for food and traditional medicine each year,[32] and even though now illegal the trade has to some extent continued.[31][33] Smaller numbers have been exported to other countries as food, for frog leather (skin) and the pet trade.[32]

Pollution and mass deaths

Pollution from mining, agriculture and human waste has become a serious problem in the range of the Titicaca water frog.[1][3] Breathing through their skin, Titicaca water frogs easily absorb chemicals from the water. Additionally, nutrient-rich pollution from agriculture can cause algae blooms where oxygen levels plummet, asphyxiating the fully aquatic frog.[29]

Historically, smaller mass deaths occasionally occurred in this species, but they are now fairly common and since 2015 there have also been large mass deaths.[31][34] In April 2015, thousands of dead Titicaca water frogs were found in Bolivia on the shore of Lake Titicaca,[35] and in October 2016 an estimated 10,000 were found dead in the Coata River (a Lake Titicaca tributary). At least in the latter case, scientists believe pollution killed the frogs.[36][37] This is also supported by the timing of the mass deaths, which mostly occur in the rainy season where pollution likely is washed into the lake from the surroundings.[31]

Die-offs possibly are reversible. It has been observed that small Titicaca water frogs may appear in the vicinity of an affected area later, possibly recolonizing it.[29]

Introduced trout

The introduced, non-native rainbow trout likely feed on tadpoles of the Titicaca water frog, the frogs are caught as bycatch in fishing nets set for trout, and coastal pens for farming trout overlap with the frog's breeding habitat and may impact it.[1][29] Lake Saracocha was home to Titicaca water frogs of the "albiventris" form, but they have not been found in later surveys and it is suspected that introduced trout were implicated in their apparent disappearance from this location.[6]

Rainbow trout was introduced on a US initiative from their original North American range to Lake Titicaca in 1941–42 to aid the local fisheries that had relied on the smaller native fish.[38][39] The fast-growing and relatively large non-native fish (trout and Argentinian silverside) are now the most important species in local fisheries, far exceeding the fisheries for the smaller natives (Orestias and Trichomycterus).[38][39] Because of the economic importance, these fisheries, along with trout farming, are supported by the local governments, making it unlikely that they would support any initiatives to reduce or even remove the trout from the region.[29]

Disease

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a fungus that causes the disease chytridiomycosis in frogs, has been present in the Andes for a long time. Although first definitely confirmed in Lake Titicaca in a study in 2012–2016,[40] a later study of museum specimens found it in several old Titicaca water frogs, one of them collected in 1863, which is the oldest known case of the fungus in the world.[41] However, this appears to involve a much less virulent form and widespread deaths of frogs in the highlands of Bolivia and Peru only began much later, in the 1990s, likely coinciding with the spread of a far more lethal form of the fungus.[41] The rapid declines, often closely linked to chytridiomycosis, have affected several of its relatives (some of them likely now extinct),[3][42] but the disease does not appear to have seriously affected the Titicaca water frog.[17][40] This may change with global warming if the water it lives in surpasses 17 °C (63 °F) for longer periods, which is the optimum temperature for the disease (it is lethal to many frog species at 17–25 °C [63–77 °F]),[17][40] or with increasing pollution, making the Titicaca water frogs more vulnerable to infection.[23] Another factor that may afford some protection to this frog is the slightly basic water (generally pH ≥7.5) of Lake Titicaca, as the fungus has the best growth rates in neutral or slightly acidic conditions (pH 6–7).[17][40]

Conservation measures

The Titicaca water frog is regarded as one of the flagship species of Lake Titicaca,[33] and in 2019 Peru issued a 1 sol coin with an illustration of this frog as part of an endangered wildlife series.[43]

In 2013, it was one of the contenders for "ugliest animal", a humorous public vote arranged by the Ugly Animal Preservation Society, an organisation that attempts to draw attention to threatened species that lack the cuteness factor.[7]

Protection

In Peru, trade outside its native range at Lake Titicaca has been illegal in decades,[30] and in 2014 it was afforded full protection in the country, making it illegal to catch the species.[33] The Peruvian authorities have seized thousands of Titicaca water frogs that were illegally traded within the country.[30][31] In 2016–2017, it was legally protected from hunting in Bolivia.[33] Since 2016, commercial international trade has been prohibited because it is included on CITES Appendix I.[33][2]

Reserves where the frog occurs have been established,[33] and Lake Titicaca is recognized as a Ramsar site, but the protection provided by reserves in this region is often very limited.[29]

Projects

Bolivia and Peru have agreed to work together to resolve the environmental problems of Lake Titicaca, but corruption and the risk of local civil unrest might cause problems for the implementation of this.[38] In 2016, the two countries pledged to use 500 million US dollars on it, including new water treatment facilities; otherwise waste water has been led directly into the lake.[4][31]

Conservation projects specifically aimed at the Titicaca water frog have been initiated, some of them in cooperation between Bolivia and Peru, including population monitoring, studies to find the reason for the mass deaths and efforts to reduce the demand for the species as a food/traditional medicine.[33][34][35][44] Education projects have resulted in some former frog poachers instead becoming part of a handicraft collective that provides a small alternative income.[31] The possibility of offering ecotours where tourists can snorkel in a wetsuit and see the frogs is being considered at Isla de la Luna (where the species is still quite common), and a pilot project related to this was completed in 2017.[29]

In 2020, scientists from Bolivia's Science Museum and Natural History Museum, Peru's Cayetano Heredia University, Pontifical Catholic University in Ecuador, Denver Zoo in the US and the NGO NaturalWay teamed up for further conservation efforts.[45]

Captive breeding

Following its rapid decline in the wild, it was decided in the early 2000s that a secure captive population should be established, which may form the basis for future reintroductions into places where it has disappeared.[34][35][44] Early captive breeding attempts were unsuccessful;[4] the only partial success was a few tadpoles hatched at the Bronx Zoo in the United States in the 1970s, but they did not metamorphose into frogs.[46]

The first fully successful captive breeding was relatively recent: In 2010 it was first bred at Huachipa Zoo in Lima, Peru, and in 2012 it was first bred at Museo de Historia Natural Alcide d'Orbigny in Cochabamba, Bolivia.[23][47][48] The breeding center in Bolivia is supported by Berlin Zoo, Germany,[15] and also involves several other threatened Bolivian frogs.[49] As a result of disagreement between the museum that provided space for it and the local biologists running it, it was briefly put on pause in 2018,[29] but has since been continued.[49]

In 2015, the breeding project initiated in Peru was expanded when a group of Titicaca water frogs bred at Huachipa Zoo was sent to Denver Zoo, United States,[23][46] which already supported the effort at Huachipa Zoo and was involved in the establishment of a laboratory and program working with the frogs at the Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru.[48] The first successful captive breeding outside its native South America happened at the Denver Zoo in 2017–2018 (first tadpoles in 2017, first metamorphosis into young frogs in 2018).[50][51] In 2019, some offspring from Denver were transferred to other US zoos and some to Chester Zoo in the United Kingdom, which redistributed them among several European zoos in an attempt of establishing another safe population. Among the European institutions, Diergaarde Blijdorp, Münster Zoo, Prague Zoo, Wrocław Zoo and WWT Slimbridge already managed to breed it in the first year.[52]

In early 2019 (prior to the breeding at several European institutions and not counting those at the breeding center in Bolivia), there were about 3,000 Titicaca water frogs at the breeding center in Peru, and 250 in zoos in North America and Europe.[53] Captives have lived for up to 20 years.[23]

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2020). "Telmatobius culeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T57334A178948447. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T57334A178948447.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Stuart, S.; M. Hoffmann; J. Chanson; N. Cox; R. Berridge; P. Ramani; B. Young, eds. (2008). Threatened Amphibians of the World. Lynx Edicions. pp. 101, 410–419. ISBN 978-84-96553-41-5.

- Lee, D.; A.T. Chang (17 January 2019). M.S. Koo; K. Whittaker (eds.). "Telmatobius culeus". AmphibiaWeb, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- Vellard, J. (1992). "The Amphibia". In C. Dejoux; A. Iltis (eds.). Lake Titicaca: a synthesis of limnological knowledge. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 449–557. ISBN 0-7923-1663-0.

- Gill, V. (12 September 2013). "Blobfish wins ugliest animal vote". BBC News. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- Victoriano, Pedro F.; Muñoz-Mendoza, Carla; Sáez, Paola A.; Salinas, Hugo F.; Muñoz-Ramírez, Carlos; Sallaberry, Michel; Fibla, Pablo; Méndez, Marco A. (2015). "Evolution and conservation on top of the world: Phylogeography of the marbled water frog (Telmatobius marmoratus species complex; Anura, Telmatobiidae) in protected areas of Chile". Journal of Heredity. 106 (S1): 546–559. doi:10.1093/jhered/esv039.

- De la Riva, Ignacio; García-París, Mario; Parra-Olea, Gabriela (2010). "Systematics of Bolivian frogs of the genus Telmatobius (Anura, Ceratophryidae) based on mtDNA sequences". Systematics and Biodiversity. 8 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/14772000903526454.

- Cossel, J.; Lindquist, E.; Craig, H.; Luthman, K. (2014). "Pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in marbled water frog Telmatobius marmoratus: first record from Lake Titicaca, Bolivia". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 112 (1): 83–87. doi:10.3354/dao02778.

- McDowell, E. (29 November 1987). "The Lake Atop Bolivia". New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Quinn, J.A.; S.L. Woodward, eds. (2015). Earth's Landscape: An Encyclopedia of the World's Geographic Features. p. 404. ISBN 978-1610694452.

- Cousteau, J.; A. Landsburg (24 April 1969). "The Legend of Lake Titicaca". The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. Episode 7.

- Halliday, T. (2016). The Book of Frogs: A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred Species from around the World. University Of Chicago Press. pp. 89, 258–259, 527. ISBN 978-0226184654.

- "Titicaca water frogs". Berlin Zoo. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Mantilla Mendoza, B.; Dina Pari Quispe; Manuel Mamani Flores (2023). Reproducción de la rana gigante (Telmatobius culeus, Garman 1875) del lago Titicaca en ambientes controlados, Puno (Report). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Tayacaja Daniel Hernández Morillo (UNAT).

- Muñoz-Saravia, A.; G. Callapa; G.P.J. Janssens (2018). "Temperature exposure and possible thermoregulation strategies in the Titicaca water frog Telmatobius culeus, a fully aquatic frog of the High Andes". Endangered Species Research. 37: 91–103. doi:10.3354/esr00904.

- "Telmatobius culeus". Bolivian Amphibian Initiative. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017.

- Hutchison, V.H.; H.B. Haines; G. Engbretson (1976). "Aquatic life at high altitude: Respiratory adaptations in the Lake Titicaca frog, Telmatobius culeus". Respiration Physiology. 27 (1): 115–129. doi:10.1016/0034-5687(76)90022-0. PMID 9678.

- Hutchison, V.H. (2008). "Amphibians: Lungs' Lift Lost". Current Biology. 18 (19): R392–R393. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.006. PMID 18460323.

- Knoll, S. (2017). Nutrition of the Titicaca water frog (Telmatobius culeus) (PDF) (Master thesis). Ghent University.

- Allen, W.R. (1922). "Notes on the Andean frog, Telmatobius culeus (Garman)". Copeia. 108 (108): 52–54. doi:10.2307/1436304. JSTOR 1436304.

- Pappas, S. (27 April 2016). "Dying Breed? Zoo Toils to Save Strange 'Scrotum Frog'". Live Science. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Watson, A.S.; A.L. Fitzgerald; O.J. Damián Baldeón; R.K. Elía (2017). "Habitat characterization, occupancy and detection probability of the Endangered and endemic Junín giant frog Telmatobius macrostomus". Endangered Species Research. 32: 429–436. doi:10.3354/esr00821.

- Pérez, M.B. (1998), Dieta y ciclo gametogénico anual de Telmatobius culeus (Anura, Leptodactylidae) en el Lago Titicaca (Huiñaimarca), Higher University of San Andrés

- Muñoz Saravia, A. (2018). Foraging strategies and ecology of Titicaca water frog (Telmatobius culeus) (PhD thesis). Ghent University. hdl:1854/LU-8577989.

- Brunetti, A.E.; A. Muñoz Saravia; J.S. Barrionuevo; S. Reichle (2017). "Silent sounds in the Andes: underwater vocalizations of three frog species with reduced tympanic middle ears (Anura: Telmatobiidae: Telmatobius)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 95 (5): 335–343. doi:10.1139/cjz-2016-0177.

- Ramos Rodrigo, T.E.; J.A. Quispe Coila; R.K. Elias Piperis (2019). "Evaluación de la abundancia relativa de Telmatobius culeus en la zona litoral del lago Titicaca, Perú". Revista Peruana de Biología. 26 (4): 475–480. doi:10.15381/rpb.v26i4.17216.

- McKittrick, E. (2018). "Saving the Scrotum Frog". Earth Island Journal. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Telmatobius culeus". Amphibian Ark. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Fobar, R. (19 April 2019). "How poachers of this rare frog became its protectors". National Geographic. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Additional information on international trade Telmatobius culeus" (PDF). CITES. 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Conservation of the Titicaca water frog (Telmatobius culeus)" (PDF). CITES. 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Rescuing Titicaca Water Frog". Bolivian Amphibian Initiative. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017.

- Titicaca water frog, Stiftung Artenschutz, archived from the original on 20 June 2018

- Howard, Brian Clark (19 Oct 2016). "10,000 'Scrotum Frogs' Die Mysteriously in Lake Titicaca". National Geographic. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Collyns, Dan (19 Oct 2016). "Scientists investigate death of 10,000 endangered 'scrotum' frogs in Peru". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Bloudoff-Indelicato, M. (9 December 2015). "What Are North American Trout Doing in Lake Titicaca?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Lauzanne, L. (1992). "Fish Fauna". In C. Dejoux; A. Iltis (eds.). Lake Titicaca: a synthesis of limnological knowledge. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 405–448. ISBN 0-7923-1663-0.

- Berenguel, R.A.; R.K. Elias; T.J. Weaver; R.P. Reading (2016). "Chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, in wild populations of the Lake Titicaca frog, Telmatobius culeus, in Peru". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 52 (4): 973–975. doi:10.7589/2016-01-007. PMID 27525594. S2CID 46881923.

- Burrowes, Patricia A.; De la Riva, Ignacio (2017). "Unraveling the historical prevalence of the invasive chytrid fungus in the Bolivian Andes: implications in recent amphibian declines". Biological Invasions. 19 (6): 1781–1794. doi:10.1007/s10530-017-1390-8. S2CID 23460986.

- Mayer, L.R. (14 February 2019). "A Tale Of Two Frogs (And Some Of The Biologists Who Love Them)". Global Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Starck, J. (28 November 2019). "Peru completes circulating commemorative wildlife series". Coin World. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Titicaca: Equipo internacional rescata a la rana gigante". Erbol Digital. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017.

- "Cross-border effort to save giant 'scrotum frog'". BBC News. 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- Nicholson, K. (25 November 2015). "Endangered Lake Titicaca frogs land at the Denver Zoo". Denver Post. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Mendoza Miranda, D.P. Clark; Munoz, A. "Ampliacíon del Programa de Cría en Cautiverio de género Telmatobius en Cochabama" (PDF). Bolivian Amphibian Initiative. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- "The Titicaca Water Frog". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Hess, E. (2 July 2019). "Romeo & Juliet: Summer Of Love!". Global Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Denver Zoo hatches first Lake Titicaca frog tadpoles in North American history". Denver Zoo. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Peru". Denver Zoo. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Titicaca water frog". Zootierliste. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "The frog as an aphrodisiac". Zoo Wroclaw. 15 March 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.