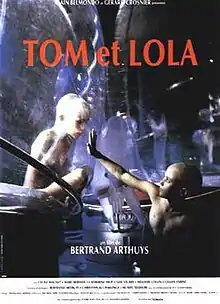

Tom et Lola

Tom et Lola (English: Tom and Lola) is a 1990 French drama film directed by Bertrand Arthuys.[1] The film is about two children with damaged immune systems who live in sealed plastic bubbles and try to escape.[1] The film was written by Arthuys, Christian de Chalonge, and Muriel Teodori.[1]

| Tom et Lola | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bertrand Arthuys |

| Written by | Bertrand Arthuys Christian Chalong Muriel Téodori |

| Produced by | Alain Belmondo Gerard Crosnier |

| Starring | Neil Stubbs Mélodie Collin Cecile Magnet Marc Berman Catherine Frot |

| Cinematography | François Catonné |

| Edited by | Jeanne Kef |

| Music by | Christophe Arthuys Jean-Pierre Fouquey |

| Distributed by | Award Films International |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

Plot

Tom and Lola are a young boy and girl who are victims of a rare disease which means that they are prevented from any contact with the outside world. They are kept inside plastic bubbles in a Paris hospital. In this aseptic and strictly controlled microcosm run by doctors especially chosen for the task, the children are left with almost no external stimuli, other than an old black and white TV set tuned to educational films about subjects such as whale song, trains, and a show called The Adventures of Tikira in Alaska. Tom's mother is in constant attendance, but her increasingly desperate attempts to beguile him have alienated her almost totally from them, and apart from Hélène, a member of the medical team who has been their nearest thing to a parent, Tom and Lola's only close attachment is to each other.

Eventually, the two children discover that by using the gauntlets that form part of their plastic pods, they are able to reach out and grasp each other's hands. One night, Tom discovers that if he pulls Lola's arms hard enough and she pulls his, they can draw their bubbles close enough for him to reach the external emergency deflate controls on her bubble. After he has activated these, Lola escapes her bubble and releases Tom from his.

Over the next few nights, the children regularly escape their plastic prisons and eventually meet Robert, a boy in another ward of the hospital. He is initially frightened by the two strange children. He thinks Tom and Lola are Martians, possibly due to their nakedness and baldness which is required for hygienic living within the bubbles. However, they quickly make friends, and he shows them other areas of the hospital, including the hydrotherapy pool, where he has a seizure after his medication drip line pulls out. The pair save him, and get him back to his room.

During another visit, Robert tells Tom and Lola that he is originally from Izoard, a small skiing village in the French Alps and shows them plans for escaping the hospital in order to return home. Tom and Lola agree this is a good idea and all three plan to escape the next night. However, when they arrive at his room the following night, Robert has already left and (they later discover) has come to grief while climbing over the hospital wall. Undeterred, Tom and Lola decide to escape anyway, having secured the address of Hélène.

Escaping the hospital, the two find their way across the Seine to a railway shunting yard in search of the train to Izoard, and climb aboard a passenger carriage where they fall asleep. They are discovered and taken to Hélène's home by a railway worker, having found on them a card with the address.

When Tom and Lola arrive at her house, her children are at home, alone as usual, as their mother spends more time with Tom and Lola at her work than with her own kids. A mutual regard and understanding develops between them, and together they contrive to set up a home situation more like the environment at the hospital, in the hope of regaining Hélène's attention. These hopes are dashed when she arrives home: her priority clearly remains the wellbeing of the escapees, and when her oldest son overhears her promise to the runaways that she will shelter them, he is disillusioned and calls the authorities.

The inevitable consequence in these circumstances is that the children will die, and the movie does not pull back from that, but treats the prospect in an allegorical, "magical realist" way. As the medical staff had planned in any case to separate the children without regard for their attachment - something they discovered only in the process of escaping - their pronostic had always been bleak.

Cast

Production

The film was directed by Bertrand Arthuys. The film was written by Bertrand Arthuys, Christian de Chalonge, and Muriel Teodori.[1]

François Catonné was the film's cinemaphotographer. Corinne Jorry was the film's costume designer.[1] The film's executive producers were Alain Belmondo and Gérard Crosnier.[1] The film's producers were Jean-François Davy, Francis Veber, and Danielle Vannier.[1]

Other production roles for the film included Laurent Barès as assistant operator, Jeanne Kef as editor, Monica Coleman as assistant editor, Frank Camhi as still photographer, Isabelle Henry as assistant director, Arthur Cloquet as camera operator, François Gédigier as sound editor, and Michèle Abbé as production designer. The film's music was composed by Christophe Arthuys and Jean-Pierre Fouquey. Guillaume Sciama, François Groult, Joël Rangod were the film's sound recordists.[1]

The film was entirely produced in France.[1] The film was produced on 35 mm film and has a run time of 97 minutes.[1]

Themes and content

The film is an unusual science fiction parable from French cinema auteur Bertrand Arthuys that recreates a libertarian perspective for children where false morality has no place. Arthuys has successfully avoided the mire of existentialist melodrama common with children's characters in situations of illness, and in doing so he manages a difficult task: to captivate the audience so that the movie is more like a carefree adventure.

Arthuys does not spare his characters' natural exposure on camera ... the nudity of the two children for roughly half the duration of the film could have led to oblivion for this movie. But it is all intrinsically subservient to his strong desire to get his message across. Neither do their tender physical expressions of mutual affection ever transgress, in degree or nature, what would reasonably be considered age-appropriate .

Lola and Tom do engage in gritty and sharply witty dialogue with the scientific team each morning, but this is largely to relieve the daily tedium.

Another striking motif is the repeated reference to an idealised heaven conceived by the two with the code phrase 'Iceberg-Alaska-Tikira', a whispered mantra as a sign of celebration or connection, accompanied with expressive signing gestures. This is later supplemented or supplanted by "Izoard!" as an aspirational symbol.

Their interaction with the adult world, populated by imbeciles who occasionally play ridiculous roles to entertain the pair from outside the bubbles, is clearly disproportionate, as if the children were a few light years ahead of the 'common sense' practised within the French hospital.

With the moralistic and sometimes hysterical persecution of artistic licence observed since the late 1980s, this film gained only a narrow VHS distribution, with regard to the fiercely competitive category of collector's items. A great example of avant-garde cinema, victimised by the approach.

The aesthetics of scenarios in the laboratory and the excessive use of white, is similar to THX 1138 by George Lucas, a kind of paradigm in the science fiction of the 1970s. This neatly evokes and reinforces the chosen environments on which the two children fixate, whose snowy and frozen purity presumably promises a freedom from the bacterial threats which enforce their captivity in civilisation.

Release

The film was released in France on January 17, 1990.[1]

In Switzerland, the film was released in 1990 and distributed by Sadfi Films.[1] In Japan, the film was released in 1991 and distributed by New Select.[1]

The film was distributed in France by AFMD, with film exports and foreign sales by Gaumont Film Company.[1]

Reception

The film received reviews from French publications, including Le Point,[2] Le Nouvel observateur,[3] Le Figaro Magazine,[4] and L'Événement du jeudi.[5]

References

- "Tom and Lola". Unifrance. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- Le point, Issues 902-909 - Page 11 (1990) - via Google Books

- Le nouvel observateur, Issues 1313-1329; Volume 1 - Page 61, 62 (1990) - via Google Books

- Le Figaro Magazine - Issues 504-507 - Page 32 (1990) - via Google Books

- L'Événement du jeudi - Issues 322-325 - Page 105 (1991) - via Google Books

External links

- Tom et Lola at IMDb