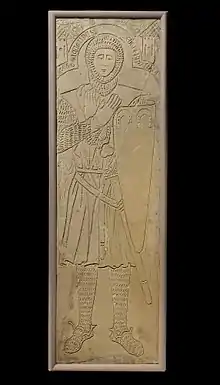

Tomb Effigy of Jacquelin de Ferrière

The Tomb Effigy of Jacquelin de Ferrière is usually on display in the Medieval Art Gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The effigy is of the French knight, Sir Jacquelin de Ferrière, who was from Montargis, near Sens in northern France. The effigy is dated between 1275-1300 CE. It is 73+3⁄4 in (187 cm) long, 24+5⁄8 in (63 cm) wide, and 5 inches (13 cm) deep, and carved into a flat limestone slab, which now has a wooden frame.[1] Effigies were often commissioned by the nobles or their families, as a means of remembrance. They would normally be found covering the sarcophagi of the knight, or installed in or near a church that the family were patrons of. Although the inscription on this effigy is not clear, most effigies contained similar inscriptions that would include the name and title, dates of birth and death–or approximates, a link between the date of death and a notable holy figure or day, and petitions of prayer that would offer pardons to those that prayed for the depicted soul–largely an attempt to create a tangible link between the nobility and divinity.[2]

Noble ideals

The age and imagery of this effigy, and most others during this period, represent the ideals of nobility during the 13th century as they wanted to be remembered. It was important for knights to be remembered as religious, of certain social status, and conforming to ideas of gender. This is why many are depicted as armed and armored, with heraldry and symbolic imagery included. These images were highly stylized and idealized, and rarely represented what the actual person looked like, instead portraying what a knight was expected to look like. The age of representation was also important. Although Jacquelin de Ferrière died while older, he is depicted, as most nobles during this period, around the age of thirty three. This age not only represented the ideal age of knights, but was also the supposed age of Jesus Christ when he was crucified.[2]

Imagery

Chainmail

Chainmail was the prominent form of armor during the 13th century. A precursor to plate armor, chainmail protected its wearer from opponents while allowing mobility, and was extremely effective against edged weapons and thrust attacks.[3]

Shield

The shield was an important part of a knight's armament. While chainmail offered protection against thrusting and edged attacks, it offered little protection against the force blunt strike from a sword or lance. The long, tapered shield offered the knight's body protection from forceful blows while on horseback or on foot.[4] The shield was also a place for knights to signify their loyalty or identity with displays of heraldry. On the shield of Jacquelin de Ferrière, horseshoes can be seen across the top of the shield.

Sword

The sword depicted is unique from other swords of this period. "Thirteenth-century pommels mostly had the shape either of a disk or a more or less pointed oval... If in an exceptional case, such as the sword on the incised tomb slab of Jaquelin de Ferriere, a trilobate pom- mel can be found, it is clearly only a scalloped variant of the disk-shaped pommel and is invariably associated with a guard of long, straight quillons."[5][6]

Spurs

When a squire became a knight, a formal ceremony would take place to welcome the newly dubbed knight. This would include an all night prayer vigil, the girding–or hanging of his sword, a blow to the cheek from the flat part of the sword by an elder, and the bestowal of his spurs. In iconography, the spurs distinguished the noble knights from other armored soldiers, such as infantrymen.[7]

Iconography

The horseshoes on the shield are an example of puns in heraldry. The pun lies within the last name, Ferrière, which is a derivative of farrier, or a smith who shoes horses.[8]

Animals were often included symbolically on effigies in the Late Middle Ages. In this effigy, two dogs can be seen flanking Jacquelin de Ferrière. The dog mostly symbolized loyalty and faithfulness, letting those who would see the effigy that person accompanied by the dogs was faithful and loyal to his family, religion, and liege lord.[9]

References

- "Tomb Effigy of Jacquline de Ferrière".

- Dressler, Rachel (2017). The Chivalirc Rhetoric of Three English Knights' Effigies. New York: Routledge. pp. 14–27. ISBN 978-0-7546-3368-6.

- Edge, D.; Paddock, J. (1988). Arms and Armour of the Medieval Knight. London: Bison.

- Oakeshott, Ewart (1960). The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armor from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry. Mineola: Dover Publications. pp. 275. ISBN 0-486-29288-6.

- Nickel, Helmut (1991). "A Crusader's Sword: Concerning the Effigy of Jean d'Alluye". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 26: 123.

- Oakeshott, Ewart (1964). The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-715-7.

- Weiss, Victoria (1978). "The Medieval Knighting Ceremony in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"". The Chaucer Review. 12 (3): 183–9. JSTOR 25093429.

- Margelony, R. Theo (September 18, 2014). "The Garden in Heraldry: A Badge of Garlic, Please". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Blogs. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Tummers, H.A. (1980). Early Secular Effigies in England: The Thirteenth Century. Netherlands: Leiden/E.J. Brill. p. 41. ISBN 90-04-06255-6.