Tôn Thất Đính

Lieutenant General Tôn Thất Đính ([toŋ˧˧ tʰək̚˦˥ ʔɗɨn˦˥], tong tək din; November 20, 1926 – November 21, 2013[1]) was an officer who served in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). He is best known as one of the key figures in the November 1963 coup that led to the arrest and assassination of Ngô Đình Diệm, the first president of the Republic of Vietnam, commonly known as South Vietnam.

Tôn Thất Đính | |

|---|---|

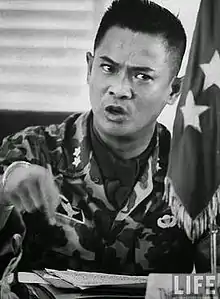

Đính in 1963 | |

| Born | November 20, 1926 Annam, Vietnam, French Indochina |

| Died | November 21, 2013 (aged 87) Santa Ana, California, US |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army of the Republic of Vietnam Cần Lao Party |

| Years of service | 1950s–1966 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | II Corps (August 1958 – December 1962) III Corps (December 1962 – January 1964) I Corps (April 1966) |

| Battles/wars | 1963 South Vietnamese coup |

| Other work | Interior Minister (November 1963 – January 1964) Senator (1967–75) |

A favorite of the ruling Ngô family, Đính received rapid promotions ahead of officers who were regarded as more capable. He converted to Roman Catholicism to curry favor with Diệm and headed the military wing of the Cần Lao party, a secret Catholic organization that maintained the Ngôs' grip on power. At the age of 32, Đính became the youngest ever ARVN general and the commander of the II Corps, but he was regarded as a dangerous, egotistical, and impetuous figure with a weakness for alcohol and partying.

In 1962, Đính, whom Diệm regarded as one of his most loyal officers, was appointed commander of the III Corps that oversaw the region surrounding the capital Saigon, making him important to the prospects of any coup. In late 1963, as Diệm became increasingly unpopular, Đính's colleagues recruited him into a coup plot by playing on his ego and pitting him against Diệm. Diệm and his brother and chief advisor Ngô Đình Nhu were aware of the plot but did not know of Đính's involvement. Nhu planned a fake coup of his own in an attempt to trap his opponents and strengthen the family's regime. Đính was placed in charge of the fake coup and sabotaged it. On November 1 the rebels' actual coup proceeded and the Ngô brothers were deposed and executed.

After the coup, Đính became one of the 12 members of the Military Revolutionary Council (MRC), but this lasted only three months before a bloodless coup by General Nguyễn Khánh. Đính and his colleagues were put under house arrest by Khánh and falsely accused of promoting a neutralist plot. The subsequent military trial collapsed. The generals were convicted of "lax morality", but were eventually allowed to resume their military service, albeit in meaningless desk jobs. Following Khánh's exile by another group of generals, Đính was appointed to command the I Corps in 1966 and ordered to put down the Buddhist Uprising, but Prime Minister Nguyễn Cao Kỳ disapproved of his conciliatory policies. Kỳ launched a successful surprise attack against Đính, who fled, but was later captured and briefly imprisoned by Kỳ. After his release, Đính worked in the media and was elected to the Senate in 1967. He served in the upper house until the fall of Saigon in April 1975, when he fled Vietnam.

Early years

Đính was born in the central highlands resort town of Da Lat on November 20, 1926,[1] into the Tôn Thất family of Huế that were relatives of the Nguyễn dynasty.[2][3] In 1943, he took a clerical job at Da Lat Court.[2] He enlisted in the Vietnamese National Army (VNA) of the French-backed State of Vietnam at Phu Bai in 1949, and was first trained as a non-commissioned officer at Mang Cá, Huế, before being accepted into the first intake of the Huế Military Academy. After one year of training, he was commissioned as a lieutenant.[1] He then trained as a paratrooper and attended Cavalry School in Saumur, France.[1][4] As a captain, he was made the commanding officer of the VNA's Mobile Task Force (GM 2) in Ninh Giang in northern Vietnam, and after graduating at the top of a Military Staff Training Course in Hanoi, was promoted to the rank of major and put in command of the forces in Duyên Hải, in the northern coastal province of Thái Bình as a battalion commander.[3] In 1952, he was made a lieutenant colonel as appointed to command the 31st Tactical Group (GM 31), based in the province of Hải Dương but also covered the adjoining provinces of Nam Định and Ninh Bình.[3] He was the Deputy Commander of Operations for Colonel Paul Vanuxem when the VNA and French Far East Expeditionary Corps withdrew from Ninh Bình to Tuy Hòa on the South Central Coast as part of Operation Auvergn following the partition of Vietnam.[3]

He became a protege of Ngô Đình Cẩn, a younger brother of Prime Minister Diệm.[5] Cẩn, who unofficially controlled the region of central Vietnam near Huế, was impressed by what he considered to be an abundance of courage on the part of Đính.[6] Within six years of enlisting in the military, Đính had risen to the rank of colonel and was made the inaugural commander of the newly formed 32nd Division based in Da Nang in the centre of the country on January 1, 1955. Đính led the unit until November 1956, during which time it was renamed the 2nd Division.[7]

Diệm deposed head of state Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum in 1955 and proclaimed himself president of the newly created Republic of Vietnam, commonly known as South Vietnam.[5] The VNA thus became the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Born into a nominally Buddhist family, Đính had converted to Catholicism in the hope of advancing his career. The change of religion was widely perceived to be a factor in his rapid promotion above more capable officers. A devout member of the Catholic minority, Diệm dedicated the country to the Virgin Mary and heavily disenfranchised and disadvantaged the Buddhist majority.[8][9]

Đính once described himself as "fearless and arrogant" and Diệm's adopted son;[10] the president was a lifelong bachelor.[11] In August 1957, he was appointed commander of the 1st Division based in Huế, the old imperial capital and Cần's base. Đính served there for one year, until he became a one-star general and received a wider-reaching command in August 1958,[6][7] making him the youngest ever ARVN general.[12] Đính's favour among the Ngô family saw him appointed in 1958 to head the military wing of the Cần Lao, the secret organisation of Vietnamese Catholics loyal to the Ngô family that maintained the family's grip on power.[8][10]

Despite the high regard in which the Ngô family held him, Đính had a poor reputation among his colleagues. Regarded by his peers as ambitious, vain and impulsive,[8][6] he was known mainly for heavily drinking in Saigon's nightclubs,[13] and the Central Intelligence Agency labelled him a "basic opportunist".[14] He was known for always wearing a paratrooper's uniform with a red beret at a steep angle, and being accompanied by a tall, uncommunicative Cambodian bodyguard.[8][15] Senior Australian Army officer Ted Serong, who worked with Đính, called him "a young punk with a gun – and dangerous".[16]

Xá Lợi Pagoda

In August 1958, Đính was made the commander of the II Corps, which oversaw the Central Highlands region mainly inhabited by indigenous tribes. He was based in the mountainous town of Pleiku and oversaw the surrounding region and the lowlands to the north of the capital of Saigon.[17] This put him in control of the 5th, 22nd and 23rd Divisions, one third of the divisions in the country.[7] At the time, the CIA had been training Montagnard tribesmen under the Village Defense Program (later to become the Civilian Irregular Defense Group) with the stated intention of resisting communist infiltration, but Đính regarded it was an attempt to divide and conquer and undermine him. He estimated that 18,000 tribesmen had been armed,[17][18] and said to Ngô Đình Nhu – one of Diệm's younger brothers and his chief adviser – that "the Americans have put an army at my back".[17][18] CIA officer Lucien Conein admitted years afterwards that Đính's claim was correct;[17] that Nhu and Diệm had no previous idea of what the Americans had been doing.[19] Đính wrote to Diệm to complain that his units were being weakened by the policy of promoting officers for political reasons,[20] despite having been a beneficiary himself of this non-merit-based policy.[8]

The reorganisation of the corps boundaries in December 1962 created a fourth region. The entire region surrounding the capital, Saigon, came under the purview of the III Corps, whereas the previous arrangement saw two corps controlling the regions to the north and south of the capital.[16] As a key supporter of Diệm, Đính was named commander of the III Corps, because the Ngô family trusted him to defend them in the face of any coup attempts.[16] Under the III Corps were the 5th and the 25th Divisions, which were located in Biên Hòa and Cu Chi, on the north-eastern and north-western outskirts of Saigon respectively.[7]

In August 1963, Nhu, who controlled the special forces and secret police, allowed Đính to have a hand in planning raids against Buddhist dissidents who had been organising at the Xá Lợi pagoda,[8] Saigon's largest.[21] The raids involved the deployment of the 5th Division into the capital.[22] Although the execution of the raids – which left hundreds dead – was primarily the responsibility of Colonel Lê Quang Tung, the special forces head,[23] Đính privately took responsibility,[24] stating to a journalist, "I have defeated Henry Cabot Lodge [the US ambassador to South Vietnam]. He came here to stage a coup d'etat, but I, Tôn Thất Đính, have conquered him and saved the country."[24] In the aftermath of the raids, Foreign Minister Vũ Văn Mẫu resigned in protest, shaved his head like a monk and sought to leave on a pilgrimage to India; Nhu ordered Đính to jail him. At the urging of another general, Đính put Mẫu under house arrest instead.[25]

During this period, Đính told a dinner guest that he had the pleasure of dining with a great national hero. When the guest asked Đính where the hero was, Đính said "it is me" and claimed to have defeated the Americans. Đính's ego had been played upon by the Ngô brothers, who had themselves reiterated this point and paid him a large cash bonus after the pagoda raids.[8][26] In the heady times after the attacks, Đính had a "somewhat incoherent" debate with his American advisor, claiming "he [Đình] was without doubt the greatest general officer in the ARVN, the saviour of Saigon ... and soon he would be the top military man in the country."[27] In a press conference after the raids, Đính claimed to have saved South Vietnam from Buddhists, communists and "foreign adventurers", a euphemism for the United States.[8][6]

After being questioned sharply, Đính quickly became angry. Ray Herndon of United Press International asked him to name the country that he was referring to, but Đính dodged the question. Herndon lampooned him by saying that a national hero should be able to identify the national enemy,[8] and asked him to call Madame Nhu, the de facto First Lady known for her anti-American comments, to get help in identifying the hostile country in question. After several reporters derisively laughed at these comments, Đính stormed out of the conference.[14][28][29]

Defection and coup

Embarrassed by the events at the press conference, Đính returned to the officers' mess at the Joint General Staff (JGS) headquarters.[29] His colleagues, led by General Trần Văn Đôn, were plotting a coup against Diệm because of the Buddhist crisis, and attempted to play on Đính's ego to convince him to join them.[6] They knew that without Đính's assistance, a coup would be difficult as his forces dominated the region surrounding the capital.[8] In a series of meetings, the other generals assured Đính that he was a national hero worthy of political authority, and claimed that Nhu had not realised how important he was in the future of the country. Đính's colleagues even bribed his soothsayer to predict his elevation to political power.[6][30] The other generals told him that the people were dissatisfied with Diệm's cabinet, that Vietnam needed dynamic young officers in politics, and that their presence would reverse the declining morale in the ARVN.[30] They advised Đính to ask Diệm to promote him to interior minister, Dương Văn Minh to defence minister and Trần Văn Minh to education minister. The other generals hoped that would reject Đính and wound his pride. As a result, Đính and his fellow generals met Diệm at the palace, where Đính asked the president to promote him to the post of interior minister. Diệm bluntly chastised Đính in front of his colleagues and ordered him out of Saigon to the Central Highlands resort town of Đà Lạt to rest.[6][28][29] Đính felt humiliated and embarrassed, having promised his colleagues that he would be successful. The Ngô brothers had been alarmed by Đính's request and put him under surveillance. Đính found out, further straining his relationship with the palace.[30] Đính agreed to join the coup, although with his ambitious nature, the other officers were skeptical and planned to have him assassinated if he tried to switch sides.[31]

With Đính and the Ngô family's increasing focus on the political usage of the army, the military situation in III Corps deteriorated badly in the second half of 1963, as personnel were redeployed into the cities. In August, he moved a unit away from Bến Tượng, which had been portrayed as a model settlement in the Strategic Hamlet Program that was supposed to isolate peasants into fortified villages to keep the Viet Cong out. While the unit was in Saigon cracking down on the Buddhists, the VC overran Bến Tượng.[27] A year earlier, the American media contingent had been invited to the opening ceremony of the settlement, which was supposed to be the flagship of the hamlet program.[32] As Đính spent most of October in the capital plotting instead of inspecting the countryside, the VC began to systematically dismantle the strategic hamlets.[27]

Plotting a fake coup

By mid-October, Diệm and Nhu knew of the coup plans, but did not know that Đính was firmly among them, although they were wary of him.[31] Nhu then decided to outwit the generals with a counter-plot. The generals heard of this and decided to counteract him.[33] The other generals were still suspicious of Đính, fearing he would betray them. Having discovered that Nhu was trying to use him to trap them and unsure of his true loyalties, they promised to make him interior minister and offered other rewards if he helped to overthrow the Ngô brothers.[34]

As part of the generals' plot, Đính sent Colonel Nguyễn Hữu Có, his deputy corps commander, to Mỹ Tho to talk to the 7th Division commander, Colonel Bùi Đình Đạm, and two regimental commanders subordinate to Đạm, and the chief of Mỹ Tho province.[28] Exhorting them to join the coup, Có stated that all the generals were in the plot except the strongly loyalist Huỳnh Văn Cao, and that Đính would soon join.[28] According to one account, Đính had intended that loyalists would report Có's activities to Diệm and Nhu so that it would give him an opportunity to orchestrate a stunt to ingratiate himself with the palace.[34]

Nhu's agents soon reported Có's activities to the palace. When the Ngô brothers confronted Đính with what occurred in Mỹ Tho, Đính feigned astonishment at his deputy's behavior, crying and vowing to have Có killed.[28][35] Nhu opposed this and stated that he wanted to keep Có alive to catch the plotters and tried to use Đính to this end.[28] Nhu ordered Đính and Tung, both of whom took their orders directly from the palace instead of the ARVN command,[36] to plan a fake coup against the government. One objective was to trick dissidents into joining the false uprising so that they could be identified and eliminated.[37] Another aim of the public relations stunt was to give a false impression of the strength of the regime.[31]

Codenamed Operation Bravo, the first stage of the scheme would involve some of Đính and Tung's loyalist soldiers, disguised as insurgents led by apparently renegade junior officers, faking a coup and vandalizing the capital.[38] Tung would then announce the formation of a "revolutionary government" consisting of opposition activists who had not consented to joining the new administration, while Diệm and Nhu would pretend to be on the run.[39] During the orchestrated chaos of the first coup, the disguised loyalists would riot and in the ensuing mayhem, kill the leading coup plotters, such as Generals Minh, Đôn, Lê Văn Kim and junior officers that were helping them. The loyalists and some of Nhu's underworld connections would also kill some figures who were assisting the conspirators, such as the titular but relatively powerless Vice President Nguyễn Ngọc Thơ, CIA agent Lucien Conein (who was on assignment in Vietnam as a military adviser) and Ambassador Lodge.[40] These would then be blamed on "neutralist and pro-communist elements".[40] A fake "counter-coup" was to follow, whereupon Tung's special forces, having left Saigon on the pretext of fighting communists, as well as Đính's regulars, would triumphantly re-enter Saigon to reaffirm the Diệm regime. Nhu would then exploit the scare to round up dissidents.[12][38][39]

Đính was put in charge of the fake coup and was allowed the additional control of the 7th Division based in Mỹ Tho, which was previously assigned to Diệm loyalist Cao, who commanded the IV Corps in the Mekong Delta. The reassignment of the 7th Division gave Đính and his III Corps complete encirclement of Saigon, and would prevent Cao from storming the capital to save Diệm as he had done during the coup attempt in 1960.[6][12][28][41]

Nhu and Tung, however, were unaware that Đính was part of the real coup plot. Đính told Tung that the fake coup needed to employ an overwhelming amount of force. He said that tanks were required "because armour is dangerous". In an attempt to outwit Tung, Đính claimed fresh troops were needed,[34] opining, "If we move reserves into the city, the Americans will be angry. They'll complain that we're not fighting the war. So we must camouflage our plan by sending the special forces out to the country. That will deceive them."[34] The loyalists were unaware that Đính's real intention was to engulf Saigon with his rebel divisions and lock Tung's men in the countryside where they could not defend the president.[39] Tung and the palace agreed to send all four Saigon-based special forces companies out of the capital on October 29.[34]

Not trusting Có, Diệm put a Catholic loyalist, Colonel Lâm Văn Phát, in command of the 7th Division on October 31.[28] According to tradition, Phát had to pay the corps commander a courtesy visit before assuming control. Đính refused to see Phát and told him to come back on Friday at 14:00, by which time the coup had already been scheduled to start. In the meantime, Đính had Đôn sign a counter-order transferring command of the 7th Division to Có. The next day, Có took the division's incumbent officers prisoner and used the unit to block loyalists from storming the capital from the south.[28]

Diệm's downfall

On November 1, 1963, the coup went ahead with Cao's troops isolated in the far south and Tung's forces outside Saigon, unable to rescue Diệm from the rebel encirclement.[6] Tung was called to the JGS headquarters at Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Base under the pretense of a routine meeting and was seized and executed. Attempts by Diệm and Nhu to make contact with Đính were blocked by other generals, who claimed that Đính was elsewhere. This led the Ngô brothers to think that Đính had been captured, still unaware that he had rebelled. The following morning, Đính was allowed to have the final word with Diệm before the brothers were arrested, allowing him to prove his loyalty to the rebel cause. Đính subsequently shouted obscenities at the Ngô brothers.[28]

Đính alleged that Nhu's contacts with the communists and threats to make a peace deal with North Vietnam had motivated the coup.[42] When Diệm and Nhu were shot dead by the arresting officers against the orders of the generals, Đính claimed he "couldn't sleep that night".[43] He boasted to the media that he and his troops were responsible for seizing broadcasting studios, the police headquarters, Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Base, and the release of hundreds of political prisoners such as monks and students.[44] He also claimed that he led the successful siege on Gia Long Palace, although the 5th Division of Colonel Nguyễn Văn Thiệu had actually carried it out.[44][45][46]

Đính saved the life of Colonel Cao Văn Viên, the commander of the Airborne Brigade, who was a Diệm loyalist. Viên's fate had been discussed during the planning phase.[47] Đính, who played mahjong with Viên's wife, convinced Minh to spare the paratroop commander, saying that Viên would not oppose the coup.[47] At the JGS meeting, Viên, who had not known of the plot, removed his insignia and resigned, and was arrested for refusing to join the coup.[48] Viên was allowed to return to his command a month later, and later became the chief of JGS for eight years.[49]

Post-Diệm

Following the coup, a Military Revolutionary Council (MRC) was formed, comprising 12 generals including Đính, each of whom had equal voting power. They appointed a cabinet mainly consisting of civilians led by Prime Minister Nguyễn Ngọc Thơ, who had been the titular Vice President under Diệm.[50] Đính was initially made interior minister, but Thơ was said to have personally opposed the appointment.[51] Eventually Minh, the head of the military junta, struck a compromise whereby Đính was made Security Minister and Administrative Affairs, which partially covered the interior ministry.[51] He was the 2nd Deputy Chairman of the MRC behind Minh and Đôn.[52] However, tension persisted as Thơ's civilian government was plagued by infighting. According to Thơ's assistant, Nguyễn Ngọc Huy, the presence of Đôn and Đính in both the civilian cabinet and the MRC paralyzed the governance process. Đính and Đôn were subordinate to Thơ in the civilian government, but as members of the MRC they were superior to him. When Thơ gave a cabinet order with which the generals disagreed, they went to the MRC and gave a counter-order.[53] Đính and the new national police chief, General Xuân, were accused of arresting people en masse, before releasing them in return for bribes and pledges of loyalty.[54] The junta performed indecisively and was heavily criticised, especially Minh, who was viewed as being too apathetic towards his country's situation. During the MRC's tenure, South Vietnam suffered more and more losses to the Vietcong.[55][56][57]

Policies

Đính was reported to have celebrated his new positions by making conspicuous appearances at Saigon nightclubs and dancing, having lifted Madame Nhu's bans on such activities. He reportedly kissed the bar dancers and ordered champagne for all present. Đính's brash behavior caused public relations problems for the junta. In interviews with The Washington Post and The New York Times, he claimed that he took a leading role in the coup because "we would have lost the war under Diệm" and saying that he participated "not for personal ambition, but for the population, the people and to get rid of Nhu". He claimed to have been the "specialist ... [who] gave the orders in only thirty minutes", keeping the plans "all in his head".[51] In an exclusive interview with Herndon, he said "You are the one who started it all, who drove me into making the coup. You are the hero of the revolution."[29] This was a reference to Herndon's sarcastic reference to Đính as a "great national hero" after the general took credit for the pagoda raids.[29] He also courted controversy with anti-American remarks, stating "On August 21, I was governor of Saigon and loyal to Diem; on November 1, I was governor of Saigon and fighting Diem; maybe in the future I'll be governor of Saigon and fighting against the Americans."[51]

Đính and the leading generals in the MRC also had a secret plan to end the communist insurgency, which claimed to be independent of the government of North Vietnam. They claimed that most of them were first and foremost southern nationalists opposed to foreign military intervention and U.S. involvement and support of Diệm. The generals agreed with this viewpoint and thought that an agreement to end the war within South Vietnam was possible.[58] The government also rebuffed American proposals to bomb North Vietnam on the grounds that such actions would cede the moral high ground, which they claimed on the basis of fighting in a purely defensive manner. However, the plans to bring the VC into the mainstream were never implemented to any degree before the government was deposed.[59]

During his time on the MRC, Đính persistently raised eyebrows with his volatile behaviour. The Americans and his colleagues found him difficult to control. General Paul Harkins, the head of the US military presence in Vietnam, advised Đính to relinquish his control of III Corps on the grounds that he was already serving as the interior minister and that a corps needed a full-time leader, but Đính refused. As III Corps surrounded the capital, the most economically productive region in South Vietnam, it had the most scope for corruption and graft.[60] Đính told U.S. embassy officials in December 1963 he was preparing to "accommodate himself to a neutralist solution for Vietnam".[61] This reportedly perturbed the Americans and was interpreted as a threat to not cooperate with the anti-communist struggle if his power was wound back.[61] US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara criticised the arrangement,[62] and in early January 1964, Đính was relieved by General Khiệm, who had been the head of the armed forces until being demoted after the coup against Diệm, and he set about overthrowing the MRC.[63]

Deposed by Nguyễn Khánh

Đính's political stay was brief, as General Nguyễn Khánh, who was disgruntled at not receiving a high position after Diệm's removal, deposed the MRC with the support of Khiệm on January 30, 1964, without firing a shot. Khánh used the coup to exact retribution against Generals Đôn, Đính, Xuan and Lê Văn Kim. Khánh had them arrested, claiming that they were part of a neutralist plot with the French government of President Charles de Gaulle to make a peace deal with North Vietnam that would not end communism. Khánh noted they had all served in the French-backed VNA prior to 1955, although he had as well.[64][65] He also accused the four generals of discussing such a plan with some visiting politicians from de Gaulle's party during a dinner, although Đính and his accused colleagues denied that the meeting was anything more than social.[66] The generals were flown to Mỹ Khe beach, near Đà Nẵng.[64][65]

Khánh presided over their trial of Đính and his colleagues on May 28, 1964.[67][68] The generals were interrogated for five and a half hours, mostly about details of their coup against Diệm, rather than the original charge of promoting neutralism. As all of the officers were involved in Diệm's overthrow, the hearings did not reveal any new information. The court deliberated for over nine hours, and when it reconvened for the verdict, Khánh stated, "We ask that once you begin to serve again in the army, you do not take revenge on anybody".[65] The tribunal then "congratulated" the generals, but found that they were of "lax morality" and unqualified to command due to a "lack of a clear political concept". They were chastised for being "inadequately aware of their heavy responsibility" and of letting "their subordinates take advantage of their positions". Đính's quartet were allowed to remain in Đà Lạt under surveillance.[65][67]

The four generals were barred from commanding troops and offices were prepared so they could participate in "research and planning".[65] Worried that the idle group would plot against him, Khánh made some preliminary arrangements to send them to the U.S. for military study, but this failed.[67][69] When Khánh was himself deposed in 1965, he handed over dossiers proving that Đính and the other generals were innocent and that his charges were dishonest, before going into exile.[70] Historian Robert Shaplen said that "the case ... continued to be one of Khánh's biggest embarrassments."[67] During the period of house arrest, Khánh briefly released Đính and Kim when the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races, known by its French acronym of FULRO, launched an uprising in the central highlands calling for autonomy for indigenous people. Đính and Kim were sent to Ban Mê Thuột in an attempt to end the standoff in September 1964, but after negotiations stalled, they conferred with Khánh and decided to order ARVN troops to crush the rebellion, which was carried out successfully.[71]

1966 Buddhist protests and senate career

With the rise to power of Nguyễn Cao Kỳ – head of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force – following Khánh's departure, returned to a command role in the army. Đính was transferred from his post as Director General of Military Training,[2] and in April 1966, he was appointed to lead I Corps, in northern South Vietnam. Đính was the third commander of the corps within five weeks. This upheaval came about after the dismissal of Lieutenant General Nguyễn Chánh Thi due to his sympathies towards Buddhist activists and because Kỳ viewed him as a personal threat. In response, Buddhist protesters brought the region to a standstill with anti-American and anti-war demonstrations, some of which descended into rioting. The protests were supported by groups of rebel I Corps soldiers and the mayor of Đà Nẵng, Nguyễn Văn Man, who had been appointed by Thi. These anti-Kỳ groups formed a coalition known as the Struggle Movement.[72] Thi's replacement, General Nguyễn Văn Chuân, refused to confront the dissidents or shut them down. He was content to allow protests provided there was no insurrection.[73]

Kỳ disapproved of Chuan's approach and replaced Chuan with Đính. Kỳ felt Đính's aggressive attitude following the Xá Lợi Pagoda raids in 1963 indicated a willingness to suppress Buddhist dissidents. Moreover, Đính was a native of central Vietnam and would have been popular with those who thought along parochial lines.[74] Đính arrived in Huế on April 15 and, after a week, announced that he had restored Saigon's authority over the region. He proclaimed that he had regained control of the radio stations in Đà Nẵng and Huế from the dissidents, and that he had convinced the mayor of Đà Nẵng to remain loyal to Saigon. Đính announced a deal whereby the Buddhists would have regular air time in return for relinquishing control of the radio station. This move was interpreted in different ways. Some felt that Đính was attempting to gain favour with the Buddhists in anticipation of Kỳ's fall from power, while Frances FitzGerald felt it was the only sensible government action during the crisis.[74] On April 19, clashes erupted in Quảng Ngãi between the Buddhists and the VNQDĐ (Vietnamese Nationalist Party), which supported the continuation of the anti-communist war, prompting Đính to forcibly restrain the two groups.[75]

Soon after, Kỳ made a surprise attack to assert government control over central Vietnam. He flew out to Đà Nẵng with his own units,[76] without consulting the Americans or officials in I Corps.[77] At this time, Đính was pursuing a policy of reconciliation Đà Nẵng and negotiation with the dissident I Corps units, and making contact with the Struggle Movement.[78] Kỳ decided to attack and sent his forces to overrun Đính's headquarters on May 15, forcing the latter to abandon his post and flee to the headquarters of U.S. General Lewis Walt. Fearing Kỳ's forces would kill him, Đính asked Walt for help and was flown to Huế, where the pro-Thi and pro-Buddhist elements were still in control. Đính was then formally replaced by General Cao.[79] Walt's assistance to Đính provoked a reaction from General William Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam. Walt and Westmoreland were often in conflict, and the latter responded to his subordinate's evacuation of Đính by imploring Kỳ to attack Huế.[76]

Kỳ's surprise attack led to conflict between the ARVN rebels and loyalists, with the American ground forces caught in the middle, effectively creating a civil war within a civil war.[76] Kỳ eventually quelled the rebellion and briefly jailed Đính, who claimed he was incarcerated for refusing to back up Kỳ's account of the conflict with the Buddhists.[80] Đính left the army and upon the nominal restoration of civilian rule, won election to the newly created Senate in 1967, as part of the Hoa Sen (Lotus) ticket.[2] He was the Chairman of Senate Defence Committee and served as a senator,[12] later serving as the leader of the Xã Hội Dân Chủ (Social Democratic) bloc.[2] In February 1968, while serving in the Senate, Đính and fellow senator and former junta colleague Đôn founded a newspaper, Công Luan,[3][81] while also serving as head of the Vietnamese Publishers Association.[82]

On April 29, a day before the fall of Saigon, Đính left for the US, initially settling in Virginia, before relocating to Garden Grove and then Westminster, in the Little Saigon area of Orange County, California.[1] In 1998, Đính claimed he felt remorse for the deposal and assassinations of the Ngô brothers, and also claimed he had opposed their policies of religious discrimination against Buddhists, which had fomented national disunity and the eventual Communist victory.[83] In 1998, his memoirs 20 Năm Binh Nghiệp – Hồi Ký của Tôn Thất Đính (Vietnamese: 20 Years in the Military – The Memoirs of Tôn Thất Đính) were published, but they were not launched for another 15 years until June 2013 at an event in Santa Ana that commemorated with the 50th anniversary of the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức during the Buddhist crisis. Đính gave the keynote address at the event, which was organized and attended by several senior members of the Vietnamese American Buddhist sangha.[84]

He died at Kindred Hospital Santa Ana on November 21, 2013, where he had been treated for several weeks, and his funeral was conducted in accordance with Buddhist tradition.[1]

Notes

- "Cựu Trung Tướng Tôn Thất Đính qua đời, thọ 87 tuổi – Tin chính". Người Việt Online. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- Văn Thư (September 22, 2008). "Tướng Tôn Thất Đính của chính quyền Sài Gòn cũ: Kẻ hoạt đầu". An Ninh Thế Giới. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- Viên Linh (December 5, 2018). "'20 Năm Binh Nghiệp,' hồi ký của Tôn Thất Đính". Người Việt. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Sheehan, p. 356.

- Jacobs, pp. 86–89.

- Karnow, pp. 307–322.

- Tucker, pp. 526–533.

- Halberstam, p. 181.

- Jacobs, pp. 88–95.

- Wright, p. 40.

- Jacobs, p. 19.

- Tucker, pp. 288–289.

- Jacobs, p. 169.

- Prochnau, pp. 442–443.

- Jones, p. 397.

- Blair (2001), p. 56.

- Hickey, pp. 100–101.

- Blair (2001), p. 62.

- Catton, p. 155.

- Toczek, p. 45.

- Karnow, p. 301.

- Blair (2001), p. 59.

- Halberstam, p. 145.

- Halberstam, p. 147.

- Sheehan, p. 357.

- Sheehan, pp. 356–357.

- Catton, p. 203.

- Halberstam, David (November 6, 1963). "Coup in Saigon: A Detailed Account". The New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- Halberstam, p. 182.

- Halberstam, pp. 182–183.

- Karnow, p. 318.

- Catton, pp. 173–175.

- Jones, p. 398.

- Jones, p. 399.

- Moyar, p. 265.

- Karnow, p. 317.

- Jones, pp. 398–399.

- Hatcher, p. 149.

- Karnow, p. 319.

- Sheehan, p. 368.

- Hatcher, pp. 145–146.

- Jones, p. 421.

- Jones, p. 429.

- Wright, p. 41.

- Jones, pp. 412–415.

- Hammer, p. 299.

- Hung, p. 79.

- Moyar, p. 267.

- Tucker, p. 62.

- Jones, pp. 99–100.

- Jones, pp. 437–438.

- Kahin, p. 648.

- Jones, p. 437.

- Shaplen, p. 221.

- Blair (1995), p. 91.

- Shaplen, pp. 220–224.

- Karnow, p. 340.

- Kahin, pp. 648–650.

- Kahin, p. 653.

- Blair (1995), p. 90.

- Blair (1995), p. 105.

- Blair (1995), p. 101.

- Blair (1995), p. 108.

- Karnow, pp. 350–351.

- Langguth, pp. 289–291.

- Kahin, p. 666.

- Shaplen, pp. 244–245.

- Blair (1995), p. 115.

- Karnow, p. 355.

- Langguth, p. 347.

- Hickey, pp. 154–160.

- Topmiller, pp. 39–43.

- Topmiller, pp. 35–39.

- Topmiller, pp. 57–58.

- Topmiller, p. 63.

- Topmiller, pp. 82–89.

- Gibbons, p. 315.

- Topmiller, p. 85.

- Topmiller, p. 86.

- Topmiller, pp. 140–141.

- Lent, p. 250.

- Isaacs, p. 337.

- Wright, p. 42.

- "Cuốn Hồi Ký Duy Nhất Của Trung Tướng Tôn Thất Đính". Việt Báo Daily News (in Vietnamese). Garden Grove, California. June 29, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

References

- Blair, Anne E. (1995). Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06226-5.

- Blair, Anne E. (2001). There to the Bitter End: Ted Serong in Vietnam. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86508-468-9.

- Catton, Philip E. (2002). Diem's Final Failure: Prelude to America's War in Vietnam. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1220-3.

- Gibbons, William Conrad (1995). The U.S. Government and the Vietnam war: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00635-0.

- Halberstam, David; Singal, Daniel J. (2008). The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6007-9.

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1987). A Death in November: America in Vietnam, 1963. New York City: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24210-4.

- Hatcher, Patrick Lloyd (1990). The Suicide of an Elite: American Internationalists and Vietnam. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1736-2.

- Hickey, Gerald Cannon (2002). Window on a War: An Anthropologist in the Vietnam Conflict. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0-89672-490-5.

- Isaacs, Arnold R. (1983). Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3060-5.

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: How the Assassinations of Diem and JFK Prolonged the Vietnam War. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505286-2.

- Kahin, George McT. (1979). "Political Polarization in South Vietnam: U.S. Policy in the Post-Diem Period". Pacific Affairs. Vancouver, British Columbia. 52 (4): 647–673. doi:10.2307/2757066. JSTOR 2757066.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam: The war, 1954–1975. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

- Lent, John A. (1971). The Asian Newspapers' Reluctant Revolution. Iowa State University Press. ISBN 0-8138-1335-2.

- Moyar, Mark (2006). Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86911-0.

- Nguyen Tien Hung; Schecter, Jerrold L. (1986). The Palace File. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-015640-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Prochnau, William (1995). Once upon a Distant War. New York City: Vintage. ISBN 0-8129-2633-1.

- Shaplen, Robert (1966). The Lost Revolution: Vietnam 1945–1965. London: André Deutsch.

- Sheehan, Neil (1988). A Bright Shining Lie:John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. New York City: Random House. ISBN 0-679-72414-1.

- Toczek, David M. (2001). The Battle of Ap Bac, Vietnam: They Did Everything But Learn From It. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31675-9.

- Topmiller, Robert J. (2006). The Lotus Unleashed: The Buddhist Peace Movement in South Vietnam, 1964–1966. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9166-1.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2000). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-040-9.

- Wright, Jackie Bong (2002). Autumn Cloud: From Vietnamese War Widow to American Activist. Herndon, Virginia: Capital Books. ISBN 1-931868-20-4.