Tragic Week (Spain)

Tragic Week (in Catalan la Setmana Tràgica, in Spanish la Semana Trágica) (25 July – 2 August 1909) was a series of violent confrontations between the Spanish army and anarchists, freemasons, socialists and republicans of Barcelona and other cities in Catalonia, Spain, during the last week of July 1909. It was caused by the calling-up of reserve troops by Premier Antonio Maura to be sent as reinforcements when Spain renewed military-colonial activity in Morocco on 9 July, in what is known as the Second Rif War. Many of these reservists were the only breadwinners for their families, while the wealthy were able to hire substitutes. The figureheads most associated with the unrest were Alejandro Lerroux and Francisco Ferrer.

| Tragic Week | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Rif War | |||

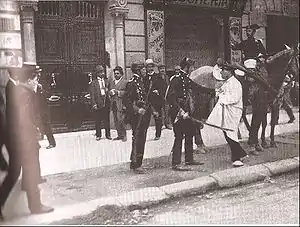

Suspects rounded up by the Civil Guard. | |||

| Date | 26 July – 2 August 1909 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Opposition to conscription and the Second Rif War Antimilitarism Anti-Clericalism | ||

| Methods | Rioting, strikes, barricades, arson and murder | ||

| Parties | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| Arrests: 1,700 Injuries: 441[1] Deaths: 104 to 150 civilians and 8 military. Five further civilians were executed after the riots. | |||

Background

Minister of War Arsenio Linares y Pombo called up the Third Mixed Brigade of Cazadores (Light Infantry), which was composed of both active and reserve units in Catalonia. Among these were 520 men who had completed active duty six years earlier, and who had not anticipated further service. Many of the Cazadores, plus other reservists, were the only breadwinners for their families. One could hire a substitute if unable or unwilling to fight, but this cost 6,000 reales which was beyond the means of most laborers, who did not earn more than 20 reales or 5 pesetas a day, barely enough to sustain themselves and their families. Accordingly the well-off were better placed to legally avoid further service than members of the working classes. Finally, conscripted service in North Africa for the perceived benefit only of wealthy mining interests was deeply unpopular.

The incident began when a party of conscripts, destined for Morocco, boarded ships owned by the marquess of Comillas, a prominent Catholic industrialist. The soldiers were the subject of patriotic addresses, the playing of the Royal March, and the distribution of religious medals by well dressed ladies. The conscripts remained silent but many of the onlookers jeered and whistled, and emblems of the Sacred Heart were thrown into the sea.[2]

General strike

These actions, coupled with anarchist, anti-militarist, and anti-colonial philosophies shared by many in the city (Barcelona later became a stronghold for the anarchists during the Spanish Civil War), resulted in the union Solidaridad Obrera - directed by a committee of anarchists and socialists - calling a general strike against Maura's call-up of the reservists on Monday 26 July 1909. Although the civil governor Ángel Ossorio y Gallardo had received ample warning of the growing discontent, acts of vandalism were provoked by elements called the jóvenes bárbaros (Young Barbarians), who were associated with the Radical Republican Party (Partido Republicano Radical) of Alejandro Lerroux.

Outbreak

By Tuesday, workers had occupied much of central Barcelona, halting troop trains and overturning trams. By Thursday, there was street fighting, with a general eruption of riots, strikes, and the burning of convents. Many of the rioters were antimilitarist, anticolonial and anticlerical. The rioters considered the Roman Catholic Church a part of the corrupt middle and upper class whose sons did not have to go to war, and much public opinion had been turned against the Church by anarchist elements within the city. Thus, not only were convents burned, but sepulchers were profaned and graves were emptied.[3] Of 112 buildings set fire to during the disturbances, 80 were church-owned or associated.

After disturbances in downtown Barcelona, civil guards and police fired on demonstrators in Las Ramblas, resulting in the construction of barricades in the streets and the proclamation of martial law. The government declaring a "state of war", ordered troops to end the revolt. Working class conscripts recruited from Barcelona and already stationed in the city, were considered unreliable under the circumstances. Accordingly, other army units were brought in from Valencia, Zaragoza, Pamplona and Burgos. These ended the revolt, causing dozens of deaths.

Aftermath

Police and army casualties were 8 dead and 124 wounded, while 104 to 150 civilians were reportedly killed. More than 1,700 individuals were indicted in military courts for "armed rebellion". Five were sentenced to death and executed (including Francesc Ferrer, founder of the Escuela Moderna); 59 received sentences of life imprisonment. Alejandro Lerroux fled into exile.

General European condemnation in the press was immediate. King Alfonso XIII, alarmed by the reaction at home and abroad, dismissed Premier Antonio Maura from power, replacing him with Segismundo Moret.

References

- Dalmau, A. (2009). Set dies de fúria: Barcelona i la Setmana Trágica. Columna. pp. 59-60.

- Mary Vincent, Spain 1833 - 2002 p.103

- Dolors Marín, "Barcelona en llamas: La Semana Trágica", La Aventura de la Historia, Año 11, no. 129, p. 47.

Sources

- (in English) Carolyn P. Boyd, Praetorian Politics in Liberal Spain, The Library of Iberian Resources Online

- (in English) Ullman, Joan Connelly. The Tragic Week: A Study of Anticlericalism in Spain, 1875–1912. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968.

- (in Spanish) Historia de conflictos

- Andreu Martín: Barcelona Trágica (Ediciones B, 2009 -castellano-); (Edicions Ara, 2009 -catalán-)