Transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage,[1] that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single railroad or over those owned or controlled by multiple railway companies along a continuous route. Although Europe is crisscrossed by railways, the railroads within Europe are usually not considered transcontinental, with the possible exception of the historic Orient Express. Transcontinental railroads helped open up unpopulated interior regions of continents to exploration and settlement that would not otherwise have been feasible. In many cases they also formed the backbones of cross-country passenger and freight transportation networks. Many of them continue to have an important role in freight transportation and some like the Trans-Siberian Railway even have passenger trains going from one end to the other.

North America

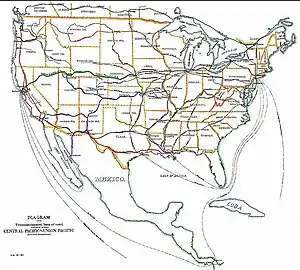

United States

A transcontinental railroad in the United States is any continuous rail line connecting a location on the U.S. Pacific coast with one or more of the railroads of the nation's eastern trunk line rail systems operating between the Missouri or Mississippi Rivers and the U.S. Atlantic coast. The first concrete plan for a transcontinental railroad in the United States was presented to Congress by Asa Whitney in 1845.[2]

A series of transcontinental railroads built over the last third of the 19th century created a nationwide transportation network that united the country by rail. The first of these, the 3,103 km (1,928 mi) "Pacific Railroad", was built by the Central Pacific Railroad and Union Pacific Railroad, as well as the Western Pacific Railroad (1862-1870), to link the San Francisco Bay at Alameda, California, with the nation's existing eastern railroad network at Omaha, Nebraska/Council Bluffs, Iowa — thereby creating the world's second transcontinental railroad when it was completed from Omaha to Alameda on September 6, 1869. (The first transcontinental railroad was the Panama Railroad of 1855.) Its construction was made possible by the US government under Pacific Railroad Acts of 1862, 1864, and 1867. Its original course was very close to current Interstate 80.

Transcontinental railroad

The U.S.'s first transcontinental railroad was built between 1863 and 1869 to join the eastern and western halves of the United States. Begun just before the American Civil War, its construction was considered to be one of the greatest American technological feats of the 19th century. Known as the "Pacific Railroad" when it opened, this served as a vital link for trade, commerce, and travel and opened up vast regions of the North American heartland for settlement. Shipping and commerce could thrive away from navigable watercourses for the first time since the beginning of the nation. Much of this route, especially on the Sierra grade west of Reno, Nevada, is currently used by Amtrak's California Zephyr, although many parts have been rerouted.[3]

The transcontinental railroad provided fast, safe, and cheap travel. The fare for a one-week trip from Omaha to San Francisco on an emigrant sleeping car was about $65 for an adult. It replaced most of the far slower and more hazardous stagecoach lines and wagon trains. The number of emigrants taking the Oregon and California Trails declined dramatically. The sale of the railroad land grant lands and the transport provided for timber and crops led to the rapid settling of the "Great American Desert".[4]

The Union Pacific recruited laborers from Army veterans and Irish immigrants, while most of the engineers were ex-Army men who had learned their trade keeping the trains running during the American Civil War.[5]

The Central Pacific Railroad faced a labor shortage in the more sparsely settled West. It recruited Cantonese laborers in China, who built the line over and through the Sierra Nevada mountains and then across Nevada to their meeting in northern Utah. Chinese workers made up ninety percent of the workforce on the line.[6] The Chinese Labor Strike of 1867 was peaceful, with no violence, organized across the entire Sierra Nevada route, and was carried out according to a peaceful Confucian model of protest.[7] The strike began with the Summer Solstice in June, 1867 and lasted for eight days.[8]

Land Grants

The Transcontinental Railroad required land and a complex federal policy for purchasing, granting, conveying land. Some of these land-related acts included:

- One motive for the Gadsden Purchase of land from Mexico in 1853 was to obtain suitable terrain for a southern transcontinental railroad, as the southern portion of the Mexican Cession was too mountainous. The Southern Pacific Railroad was completed in 1881.

- The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 (based on an earlier bill in 1856) authorized land grants for new lines that would "aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific ocean".[9]

- The rails of the "first transcontinental railroad" were joined on May 10, 1869, with the ceremonial driving of the "Last Spike" at Promontory Summit, Utah, after track was laid over a 2,826 km (1,756 mi) gap between Sacramento and Omaha, Nebraska/Council Bluffs, Iowa[10] in six years by the Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad.[11] Although through train service between Omaha and Sacramento was in operation as of that date, the road was not completed to the Pacific Ocean until September 6, 1869, when the first through train reached San Francisco Bay at Alameda Terminal, and on November 8, 1869, when it reached the terminus at Oakland Long Wharf. Later, November 6, 1869, was deemed to be the official completion date of the Pacific Railroad.[12] (A physical connection between Omaha, Nebraska, and the statutory Eastern terminus of the Pacific road at Council Bluffs, Iowa, located immediately across the Missouri River was also not finally established until the opening of UPRR railroad bridge across the river on March 25, 1873, prior to which transfers were made by ferry operated by the Council Bluffs & Nebraska Ferry Company.[13][14])

- The first permanent, continuous line of railroad track from coast to coast was completed 15 months later on August 15, 1870, by the Kansas Pacific Railroad near its crossing of Comanche Creek at Strasburg, Colorado. This route connected to the eastern rail network via the Hannibal Bridge across the Missouri River at Kansas City completed June 30, 1869, passed through Denver, Colorado, and north to the Union Pacific Railroad at Cheyenne, Wyoming, making it theoretically possible for the first time to board a train at Jersey City, New Jersey, travel entirely by rail, and step down at the Alameda Wharf on San Francisco Bay in Oakland. This singularity existed until March 25, 1873 when the Union Pacific constructed the Missouri River Bridge in Omaha.[15][16]

Subsequent transcontinental routes

- Almost 12 years after Promontory Summit, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) constructed the second transcontinental railroad, building eastwards through the Gadsden Purchase, which had been acquired from Mexico in 1854 largely with the intention of providing a route for a railroad connecting California with the Southern states. This line was completed with milestones and ceremonies in 1881 and 1883:

- March 8, 1881: the SP met the Rio Grande, Mexico and Pacific Railroad (a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway) with a "silver spike" ceremony at Deming, New Mexico, connecting Atchison, Kansas, to Los Angeles.[17]

- December 15, 1881: the SP met the Texas and Pacific Railway (T&P) at Sierra Blanca, Texas, connecting eastern Texas to Los Angeles.

- January 12, 1883: the SP completed its own southern section, meeting its subsidiary Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway at the Pecos River in Texas, and linking New Orleans to Los Angeles.

- In Colorado, the 3-foot gauge Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) extended its route from Denver via Pueblo across the Rocky Mountains to Grand Junction in 1882. In central Utah, the D&RG acquired a number of independent narrow gauge companies, which were incorporated into the first (1881-1889) Denver and Rio Grande Western Railway (D&RGW). Tracks were extended north through Salt Lake City, while simultaneously building south and eastward toward Grand Junction. The D&RG and the D&RGW were linked on March 30, 1883, the extension to Ogden (where it met the Central Pacific) was completed on May 14, 1883, and through traffic between Denver and Ogden began a few days later. The break of gauge made direct interchange of rolling stock with standard gauge railroads at both ends of this bridge line impossible for several years. The D&RG in 1887 began rebuilding its mainline in standard gauge, including a new route and tunnel at Tennessee Pass. The first D&RGW was reincorporated as the Rio Grande Western (RGW) in June 1889 and immediately began the conversion of track gauge. Standard gauge operations linking Ogden and Denver were completed on November 15, 1890.[18]

- The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad completed its route connecting the AT&SF at Albuquerque, New Mexico, via Flagstaff, Arizona, to the Southern Pacific at Needles, California, on August 9, 1883. The SP line into Barstow was leased by the A&P in 1884 (and purchased in 1911); this gave the AT&SF (the A&P's parent company) a direct route into Southern California.[17] This route now forms the western portion of BNSF's Southern Transcon.

- The Northern Pacific Railway (NP) completed the fifth independent transcontinental railroad on August 22, 1883, linking Chicago with Seattle. The Completion Ceremony was held on September 8, 1883, with former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant contributing to driving the Final Spike.

- The California Southern Railroad (chartered January 10, 1882) was completed from National City on San Diego Bay via Temecula Cañon to Colton and San Bernardino in September, 1883, and extended through the Cajon Pass to Barstow, a junction of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, in November, 1885. In September, 1885, the line of the Southern Pacific from Colton to Los Angeles, a distance of 93 km (58 mi), had been leased by the California Central with equal rights and privileges thus allowing the Santa Fe's Transcontinental route to be completed by the connection with the California Southern and A&PRR. The SP grade was used until the completion of the California Central's own line between San Bernardino and Los Angeles in June, 1887, a distance of 101.13 km (62.84 mi), which was part of the old Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley Railroad, which had been acquired by purchase. In August, 1888, the California Central completed its Coast Division south from Los Angeles to a junction with the California Southern Railroad near Oceanside, a distance of 130.20 km (80.90 mi), and these two divisions comprised the main line of the California Central, forming, in connection with the California Southern, a direct line between Southern California and the East by way of the Atlantic and Pacific and Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroads.[19]

- The Great Northern Railway was built, without federal aid, by James J. Hill in 1893; it stretched from St. Paul to Seattle.

- The Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific reached Santa Rosa, New Mexico, from the east in late 1901, shortly before the El Paso & Northeastern arrived from the southwest. The two were connected on February 1, 1902, thus forming an additional link between the Midwest and southern California.[17] Through passenger service was provided by the Golden State Limited (Chicago—Kansas City—Tucumcari—El Paso—Los Angeles) jointly operated by the Rock Island and the Southern Pacific (EP&NE's successor) from 1902 to 1968.

- The San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad completed its line connecting Los Angeles through Las Vegas to Salt Lake City on May 1, 1905. Through passenger service from Chicago to Los Angeles was provided by Union Pacific's Los Angeles Limited from 1905 to 1954, and the City of Los Angeles from 1936 to 1971.

- The Western Pacific Railway (WP), financed by the Denver & Rio Grande on behalf of the Gould System, completed its new line (the Feather River Route) from Oakland to Ogden in 1909, in direct competition with the Southern Pacific's existing route. Through passenger service (Oakland-Salt Lake City-Denver-Chicago) was provided by the Exposition Flyer 1939 to 1949 and its successor, the California Zephyr 1949 to 1970, both jointly operated by the WP, the D&RGW and the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy.

- In 1909, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul (or Milwaukee Road) completed a privately built Pacific extension to Seattle. On completion, the line was renamed the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific. Although the Pacific Extension was privately funded, predecessor roads did benefit from the federal land grant act, so it cannot be said to have been built without federal aid.

- John D. Spreckels completed his privately funded San Diego and Arizona Railway in 1919, thereby creating a direct link (via connection with the Southern Pacific lines) between San Diego, California and the Eastern United States. The railroad stretched 238 km (148 mi) from San Diego to Calexico, California, of which 71 km (44 mi) were south of the border in Mexico.

- In 1993, Amtrak's Sunset Limited daily railroad train was extended eastward to Miami, Florida, later rerouted to Orlando, making it the first regularly scheduled transcontinental passenger train route in the United States to be operated by a single company. Hurricane Katrina cut this rail route in Louisiana in 2005. The train now runs from Los Angeles to New Orleans.

The Gould System

George J. Gould attempted to assemble a truly transcontinental system in the 1900s. The line from San Francisco, California, to Toledo, Ohio, was completed in 1909, consisting of the Western Pacific Railway, Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, Missouri Pacific Railroad, and Wabash Railroad. Beyond Toledo, the planned route would have used the Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad (1900), Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway, Little Kanawha Railroad, West Virginia Central and Pittsburgh Railway, Western Maryland Railroad, and Philadelphia and Western Railway, but the Panic of 1907 strangled the plans before the Little Kanawha section in West Virginia could be finished. The Alphabet Route was completed in 1931, providing the portion of this line east of the Mississippi River. With the merging of the railroads, only the Union Pacific Railroad and the BNSF Railway remain to carry the entire route.

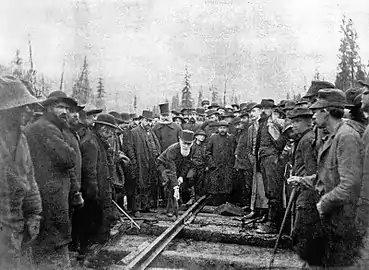

Canada

The completion of Canada's first transcontinental railway with the driving of the Last Spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia, on November 7, 1885, was an important milestone in Canadian history. Between 1881 and 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) completed a line that spanned from the port of Montreal to the Pacific coast, fulfilling a condition of British Columbia's 1871 entry into the Canadian Confederation. The City of Vancouver, incorporated in 1886, was designated the western terminus of the line. The CPR became the first transcontinental railway company in North America in 1889 after its International Railway of Maine opened, connecting CPR to the Atlantic coast.

The construction of a transcontinental railway strengthened the connection of British Columbia and the North-West Territories to the country they had recently joined, and acted as a bulwark against potential incursions by the United States.

Subsequently, two other transcontinental lines were built in Canada: the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) opened another line to the Pacific in 1915, and the combined Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTPR)/National Transcontinental Railway (NTR) system opened in 1917 following the completion of the Quebec Bridge, although its line to the Pacific opened in 1914. The CNoR, GTPR, and NTR were nationalized to form the Canadian National Railway, which currently is now Canada's largest transcontinental railway, with lines running all the way from the Pacific Coast to the Atlantic Coast.

Central America (inter-oceanic lines)

Panama (South America)

The first railroad to directly connect two oceans (although not by crossing a broad "continental" land mass[20]) was the Panama Rail Road. Opened in 1855, this 77 km (48 mi) line was designated instead as an "inter-oceanic"[21] railroad crossing Country at its narrowest point, the Isthmus of Panama, when that area was still part of Colombia. (Panama split off from Colombia in 1903 and became the independent Republic of Panama). By spanning the isthmus, the line thus became the first railroad to completely cross any part of the Americas and physically connect ports on the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Given the tropical rain forest environment, the terrain, and diseases such as malaria and cholera, its completion was a considerable engineering challenge. The construction took five years after ground was first broken for the line in May, 1850, cost eight million dollars, and required more than seven thousand workers drawn from "every quarter of the globe."[22]

This railway was built to provide a shorter and more secure path between the United States' East and West Coasts. This need was mainly triggered by the California Gold Rush. Over the years the railway played a key role in the construction and the subsequent operation of the Panama Canal, due to its proximity to the canal. Currently, the railway operates under the private administration of the Panama Canal Railroad Company, and its upgraded capacity complements the cargo traffic through the Panama Canal.

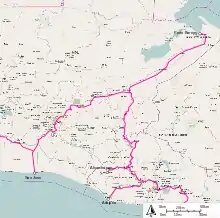

Guatemala

A second Central American inter-oceanic railroad began operation in 1908 as a connection between Puerto San José and Puerto Barrios in Guatemala, but ceased passenger service to Puerto San José in 1989.

Costa Rica

A third Central American inter-oceanic railroad began operation in 1910 as a connection between Puntarenas and Limón in 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge. It currently (2019) sees no passenger service.

South America

There is activity to revive the connection between Valparaíso and Santiago in Chile and Mendoza, Argentina, through the Transandino project. Mendoza has an active connection to Buenos Aires. The old Transandino began in 1910 and ceased passenger service in 1978 and freight 4 years later. Technically a complete transcontinental link exists from Arica, Chile, to La Paz, Bolivia, to Buenos Aires, but this trans-Andean crossing is for freight only.

On December 6, 2017 the Brazilian President Michel Temer and his Bolivian counterpart Evo Morales signed an agreement for an Atlantic - Pacific railway. The construction will start in 2019 and will be finished in 2024. The new railway is planned to be 3750 km in length. There are two possible tracks in discussion: Both have an Atlantic end in Santos, Brazil but the Pacific ends are in Ilo, Peru and Matarani, Peru.[23]

Another longer Transcontinental freight-only railroad linking Lima, Peru, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil is under development.

Eurasia

- The first transcontinental railroad in Europe, that connected the North Sea or the English Channel with the Mediterranean Sea, was a series of lines that included the Paris–Marseille railway, in service 1856. Multiple railways north of Paris were in operation at that time, such as Paris–Lille railway and Paris–Le Havre railway.

- The second connection between the seas of Northern Europe and the Mediterranean Sea, was a series of lines finalized in 1857 with the Austrian Southern Railway, Vienna–Trieste. There were before that railroad connections Hamburg–Berlin–Wroclaw–Vienna (including Berlin–Hamburg Railway, Berlin–Wrocław railway, Upper Silesian Railway and Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway). The Baltic Sea was also connected through the Lübeck–Lüneburg railway.

- The Trans-Siberian Railway, completed in 1905, was the first network of railways connecting Europe and Asia. It connects Western Russia to the Russian Far East,[24] and is the longest railway line in the world,[25] with a length of over 9,289 kilometres (5,772 miles). The railway starts from Russia's capital Moscow, which is the largest city in Europe, and ends at Vladivostok, on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. Expansion of the railway system continues as of 2021,[26] with connecting rails going into Asia, namely Mongolia, China and North Korea.[27] There are also plans to connect Tokyo, the capital of Japan, to the railway.[27]

- A second rail line connects Istanbul in Turkey with China via Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. This route imposes a break of gauge at the Iranian border with Turkmenistan and at the Chinese border. En route there is a train ferry in eastern Turkey across Lake Van. The European and Asian parts of Istanbul was linked 2019 linked by the Marmaray undersea tunnel, before that by train ferry. There is no through service of passenger trains on the entire line. A uniform gauge connection was proposed in 2006, commencing with new construction in Kazakhstan. A decision to make the internal railways of Afghanistan 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) gauge potentially opens up a new standard gauge route to China, since China abuts this country.[28]

Asia

- The Trans-Asian Railway is a project to link Singapore to Istanbul and is to a large degree complete with missing pieces primarily in Myanmar. The project has also linking corridors to China, the central Asian states, and Russia. This transcontinental line unfortunately uses a number of different gauges, 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in), 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in), 1,520 mm (4 ft 11+27⁄32 in) and 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in), though this problem may be lessened with the use of variable gauge axle systems such as the SUW 2000.

- The TransKazakhstan Trunk Railways project by Kazakhstan Temir Zholy will connect China and Europe with standard gauge 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in). Construction is set to start in 2006. Initially the line will go to western Kazakhstan, south through Turkmenistan to Iran, then to Turkey and Europe. A shorter to-be-constructed 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) link from Kazakhstan is considered going through Russia and either Belarus or Ukraine.

- The Baghdad Railway connects Istanbul with Baghdad and finally Basra, a sea port at the Persian Gulf. When its construction started in the 1880s it was in those times a Transcontinental Railroad.

Australia

East-west

- Australia's east–west transcontinental rail corridor, consisting of lines built to three different track gauges, was completed in 1917, when the Trans-Australian Railway was opened between Port Augusta, South Australia and Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. This line, built by the federal government as a federation commitment, filled the last gap in the lines between the mainland state capitals of Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth. Passengers and freight alike suffered from time-consuming breaks of gauge: a Perth–Brisbane journey at that time involved two standard gauge 1435 mm (4 ft 81⁄2 in) lines, a broad gauge 1600 mm (5 ft 3 in) line, and three of 1067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge.

- In the 1940s and 1960s, steps were taken to progressively reduce the huge inefficiencies caused by the numerous historically imposed breaks of gauge by linking the mainland capital cities with lines all of standard gauge.

- In 1970, the route across the continent was completed to standard gauge and a new, all-through passenger train, the Indian Pacific was inaugurated.

- An east–west transcontinental line across northern Australia from the Pilbara to the east coast – more than 1000 km (600 mi) north of the Sydney-Perth rail corridor – was proposed in 2006 by Project Iron Boomerang to connect iron ore mining in the Pilbara and coal mining in the Bowen Basin in Queensland, with steel manufacturing plants at both ends.[29]

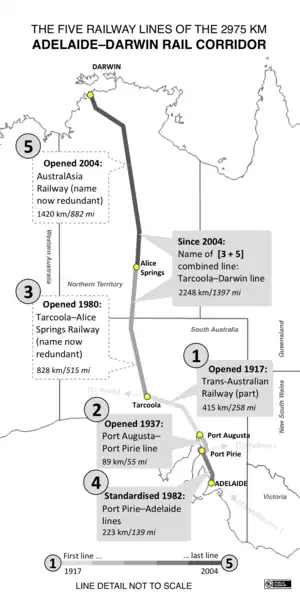

North–south

- Australia's north–south transcontinental rail corridor was built in stages during the 20th century, leaving a 1420-kilometre (880-mile) gap to be finished after the 828 kilometres (514 miles) Tarcoola to Alice Springs section was completed in 1980.[30] That final section, from Alice Springs to Darwin, was opened in 2004. The total length of the corridor, from Adelaide to Darwin, is 2975 kilometres (1849 miles). Completion of the corridor ended 126 years of freight and passengers alike having to be transferred between trains on tracks of different gauges: the corridor is now entirely 1435 mm (4 ft 81⁄2 in) standard gauge. The corridor is an important route for freight. An upmarket experiential tourism passenger train, The Ghan, operated by Journey Beyond, makes the journey once a week in each direction from Adelaide to Darwin,[31] and the company's east–west Indian Pacific runs on the southernmost 727 kilometres (452 miles) before heading west to Perth.[32] There is no intermediate passenger traffic on the line.

- In 2018, the Australian Rail Track Corporation started building a 1700-kilometre (1000-mile) standard gauge fast-freight railway from Melbourne to Brisbane, known as the Inland Railway. As of June 2022, completion was anticipated in 2027.[33]

Africa

East-west

- There are several ways to cross Africa transcontinentally via connecting east–west railways. One is the Benguela railway, completed in 1929. It starts in Lobito, Angola, and connects through Katanga to the Zambia railways system. From Zambia several ports are accessible on the Indian Ocean: Dar es Salaam in Tanzania through the TAZARA, and, through Zimbabwe, Beira and Maputo in Mozambique. The Angolan Civil War has made the Benguela line largely inoperative, but efforts are being taken to restore it. Another west–east corridor leads from the Atlantic harbours in Namibia, either Walvis Bay or Luderitz to the South African rail system that, in turn, links to ports on the Indian Ocean ( i.e. Durban, Maputo).

- A 1015 km gap in the east–west line between Kinshasa and Ilebo filled by riverboats could be plugged with a new railway.[34]

- There are two proposals for a line from the Red Sea to the Gulf of Guinea, including TransAfricaRail.

- In 2010 a proposal sought to link Dakar to Port Sudan. Thirteen countries would be on the main route; another six would be served by branches.

North-south

- A north-south transcontinental railway had been proposed by Cecil Rhodes, who termed it the Cape-Cairo railway. This system would act as a direct route from the northernmost British possession in Africa, Egypt, to the southernmost one, the Cape Colony. The project was never completed. During its development, a competing French colonial project for a competing line from Algiers or Dakar to Abidjan was abandoned after the Fashoda incident. This line would have had four gauge islands in three gauges.

- An extension of Namibian Railways is being built in 2006 with the possible connection to Angolan Railways.

- Libya has proposed a Trans-Saharan Railway connecting possibly to Nigeria which would connect with the proposed AfricaRail network.

African Union of Railways

- The African Union of Railways has plans to connect the various railways of Africa including the Dakar-Port Sudan Railway.

References

- Trackage OnLine Def

- Bain, David Haward (1999). Empire Express; Building the first Transcontinental Railroad. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-80889-X.

- Cooper, Bruce Clement (2005). Riding the Transcontinental Rails: Overland Travel on the Pacific Railroad 1865–1881. Philadelphia: Polyglot Press, 445 pages. ISBN 1411599934. p. 1-15

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (2012)

- Collins, R.M. (2010). Irish Gandy Dancer: A tale of building the Transcontinental Railroad. Seattle: Create Space. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-4528-2631-8.

- Chang, Gordon H; Fishkin, Shelley Fisher (2019). The Chinese and the iron road: Building the transcontinental railroad. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503608290.

- Ryan, Patrick Spaulding (2022-05-11). "Saving Face Without Words: A Confucian Perspective on The Strike of 1867". International Journal of Humanities, Art and Social Studies (IJHAS) (forthcoming). doi:10.2139/ssrn.4067005. S2CID 248036295. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- Ibid.

- "An Act to aid in the construction of a railroad and telegraph line from the Missouri river to the Pacific ocean, and to secure to the government the use of the same for postal, military, and other purposes 12 Stat. 489, July 1, 1862

- Executive Order of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Fixing the Point of Commencement of the Pacific Railroad at Council Bluffs, Iowa, March 7, 1864 38th Congress, 1st Session SENATE Ex. Doc. No. 27

- "Ceremony at "Wedding of the Rails," May 10, 1869 at Promontory Point, Utah". World Digital Library. 1869-05-10. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- The Official "Date of Completion" of the Transcontinental Railroad under the Provisions of the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, et seq., as Established by the Supreme Court of the United States to be November 6, 1869. (99 U.S. 402) 1879 as transcribed from "ACTS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS OF CONGRESS, AND DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES RELATING TO THE UNION PACIFIC, CENTRAL PACIFIC, AND WESTERN PACIFIC RAILROADS." WASHINGTON: Government Printing Office. 1897

- Omaha's First Century Installment V. — The Proud Era: 1870–1885

- UPRR Museum, Council Bluffs, IA Archived 2009-09-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Fink, Robert (July 27, 1970). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Registration Form: Comanche Crossing of the Kansas Pacific Railroad". NP Gallery. National Park Service. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- Borneman, Walter R. (2014-11-18). Iron Horses: America's Race to Bring the Railroads West. Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316371797.

- Myrick, David, New Mexico's Railroads, A Historic Survey, University of New Mexico Press 1990. ISBN 0-8263-1185-7

- Beebe, Lucius and Clegg, Charles, "Rio Grande, Mainline of the Rockies", Howell-North Books 1962.

- "Eleventh Annual Report of the Board of Railroad Commissioners of the State of California for the year ending December 31, 1890" Sacramento: California State Office, J.D. Young, Superintendent of State Printing, 1890. p. 21

- Otis, F.N.,"Illustrated History of the Panama Railroad" (Harper & Bros., New York, 1861), p. 12

- "A Great Enterprise" The Portland (Maine) Transcript [Newspaper], February 17, 1855.

- Otis, p. 35

- "Transkontinentale Eisenbahn: Brasilien und Bolivien gehen das Jahrhundertprojekt an". Faz.net.

- "Lonely Planet Guide to the Trans-Siberian Railway" (PDF). Lonely Planet Publications. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2012.

- Thomas, Bryn; McCrohan, Daniel (2019). Trans-Siberian Handbook: The Guide to the World's Longest Railway Journey with 90 Maps and Guides to the Route, Cities and Towns in Russia, Mongolia and China (10 ed.). Trailblazer Publications. ISBN 978-1912716081. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "New 8,400 mile train journey will connect London to Tokyo". The Independent. 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- "Russia offers a bridge across history to connect Tokyo to the Trans-Siberian railway". siberiantimes.com. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Railway Gazette International | month=October | year=2010 | page=63 (with map)

- "PIB Project Update" (PDF). Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. AusIMM Cairns. August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- History of the railway Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine AustralAsia Railway Corporation

- "Fares and timetables". Journey Beyond Rail. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "The Indian Pacific 2022 fares and timetables". Journey Beyond Rail. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- "What is Inland Rail". Inland Rail. Australian Rail Track Corporation. 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- "Afdb.org". Archived from the original on 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

Further reading

- Glenn Williamson, Iron Muse: Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.