Treatise on Man

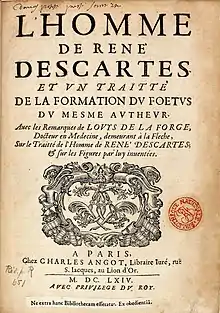

The Treatise on Man (French: L'Homme) is an unfinished treatise by René Descartes written in the 1630s and published posthumously, firstly in 1662 in Latin, then in 1664 in French by Claude Clerselier. The 1664 edition is accompanied by a short text, The Description of the Human Body and All Its Functions (La description du corps humain et de toutes ses fonctions), also known as the Treatise on the Formation of the Foetus (Traité de la formation du fœtus), the remarks of Louis La Forge and the translated preface from the Latin edition by Florent Schuyl.

Editorial context

René Descartes begins to write the treaty in the 1630s and gives up publishing it when he learns of Galileo's condemnation.[1]

A first version of the text appeared in Latin in 1662, edited and prefaced by Florent Schuyl, who proposed another edition in 1664 in the same language from another manuscript. The first French language edition was published the same year, edited by Claude Clerselier. It includes figures composed by Descartes, Louis de la Forge and Gérard von Gutschoven, as well as a division into 106 numbered articles by Claude Clerselier. There is attached a treatise found in Descartes' inventory under the name of Description of the human body and designated as the Treaty of the fetus by Clerselier,[2] as well as the preface by Schuyl to the Latin edition of 1662 and a long commentary by Louis de la Forge.[3]

Summary

Treatise of Man

The opening of the treatise shows its unfinished state : it announces the description of the body, then that of the soul and finally of the articulation between the two ; only the first presents itself to the reader's eyes.[4] It adopts a fictional form, describing a being similar to man regardless of any consideration of his formation and the addition of a rational soul, therefore like a machine.[5]

The first part deals with the main functions of this bodily machine : digestion, nutrition, respiration, blood circulation and the formation of animal spirits. Descartes claims that meats are digested by liquors and that part of it is converted into blood in the liver. The blood, which circulates perpetually, pushed out of the arteries by the heart, nourishes the various parts of the body. The more subtle parts of the blood go to the brain while the others descend through the vessels intended for generation. Cerebral blood produces in the pineal gland, a “very bright and very pure flame” called animal spirits.[6]

The second part explains the movement. Descartes then uses the metaphor of a fountain. Animal spirits, like water, flow through nerves, like pipes, activating muscles and tendons, compared to various springs and devices. Channels allow the spirits to move from one muscle to the opposite muscle, and to strain or relax them through the valves. Breathing, ingestion and excretion thus correspond to the alternating action of opposing muscles.[7]

The third part is devoted to the external senses of touch, sight, smell, taste and hearing. The pain comes from a tugging of severing nerves and the feeling of harshness from irregularity in their strain. The arousal of the nerves in the tongue gives rise to the taste, which in turn indicates whether a food is suitable for the body. Smell depends on nerve threads that run from the base of the brain to the nose while the auditory nerves are moved by the air leading into the ears. Descartes provides further developments on sight, describing in a review the structure of the eye, the function of three ocular humors, as well as the mechanism of vision.[8]

The fourth focuses on the inner senses of hunger, thirst, joy and sadness, as well as the role of the organs in the formation of animal spirits. Appetite arises from the action of liquor on an empty stomach, just as the air or smoke that replaces the lack of liquor in the throat induces the idea of thirst. Comparing the functions of this bodily machine to an organ, Descartes asserts that they depend "on the spirits that come from the heart, the pores of the brain through which it passes and the way these spirits are distributed in the pores." The natural inclinations are explained by the diversity of minds, itself correlated with food, air and organs.[9]

The fifth deals with the structure of the brain and the formation of different faculties. The brain is a tissue made up of concavities and threads forming a tight mesh, converging towards the gland. Sneezing and dizziness are respectively considered congestion of animal spirits towards the nasal parts or the inner surface. Common sense ideas arise from the actual presence of objects and their impression on animal spirits as they emerge from the H gland, while others are from the imagination. Memory results from more or less lasting and repeated traces left by these impressions. The convergence of minds by this gland explains both the origin of movement and the formation of an idea, which itself can result from the combination of several of them. Descartes develops the influence of the eyes on the action of the gland and the composition of the movement.[10]

The Description of the Human Body

The Description of the Human Body is also an unfinished treatise. It was written in 1647. Descartes felt knowing oneself was particularly useful. This for him included medical knowledge. He hoped to cure and prevent disease, even to slow down aging.

René Descartes believed the soul caused conscious thought. The body caused automatic functions like the beating of the heart and digestion he felt. The body was necessary for voluntary movement as well as the will. However, he believed the power to move the body was wrongly imagined to come from the soul. A sick or injured body does not do what we want or moves in ways we do not want. He believed the death of the body stopped it from being fit to bring about movement. This did not necessarily happen because the soul left the body.[11]

René Descartes believed the body could exist through mechanical means alone. This included digestion, blood circulation, muscle movement and some brain function. He felt we all know what the human body is like because animals have similar bodies and we have all seen them opened up.

He saw the body as a machine. He believed the heat of the heart somehow caused all movement of the body. Blood vessels he realized were pipes, he saw that veins carried digested food to the heart. (This was brought further by William Harvey. Harvey developed the idea of the circulation of the blood.) Descartes felt that an energetic part of blood went to the brain and there gave the brain a special type of air imbued with vital force that enabled the brain to experience, think and imagine. This special air then went through the nerves to the muscles enabling them to move.

References

- Descartes 2018, p. 9, Foreword of Delphine Antoine-Mahut.

- Descartes 2018, p. 10-13, Foreword of Delphine Antoine-Mahut.

- Descartes 2018, p. 14, Foreword of Delphine Antoine-Mahut.

- Descartes 2018, p. 10-11, Foreword of Delphine Antoine-Mahut.

- Descartes 2018, p. 15-18, Foreword of Delphine Antoine-Mahut.

- Descartes 2018, p. 127-137.

- Descartes 2018, p. 138-152.

- Descartes 2018, p. 153-176.

- Descartes 2018, p. 177-183.

- Descartes 2018, p. 184-225.

- Descartes, Rene (1998). "Description of the Human Body". In Gaukroger, Stephen (ed.). The World and Other Writings. pp. 170–205. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605727.009. ISBN 9780511605727.

Bibliography

- Descartes, René (2018). L'Homme (in French). presentation, notes, chronology and bibliography by Delphine Antoine-Mahu. Paris: Flammation. p. 545. ISBN 978-2-08-120643-4.

- Antoine-Mahut, Delphine; Gaukroger, Stephen (2016). Descartes' Treatise on Man and its Reception. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-46987-4.

External links

- René Descartes: The Description of the Human Body: summary preface in translation.

- Descartes, René (1596–1650)