Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte

The treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte (911) is the foundational document of the Duchy of Normandy, establishing Rollo, a Norse warlord and Viking leader, as the first Duke of Normandy in exchange for his loyalty to Charles III, the king of West Francia, following the Siege of Chartres. The territory of Normandy centered on Rouen, a city in the Marches of Neustria which had been repeatedly raided by Vikings since the 840s, and which had finally been taken by Rollo in 876.

The treaty

Rollo in June 911 unsuccessfully laid siege to Chartres. He was defeated in battle on 20 July 911.[1] In the aftermath of this conflict, Charles the Simple decided to negotiate a treaty with Rollo.

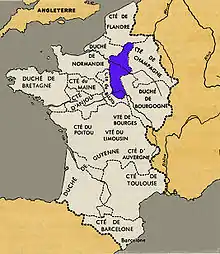

The talks, possibly led by Heriveus, the archbishop of Reims, resulted in the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte in 911. Initial proceedings with the treaty were difficult; Rollo was initially offered Flanders, though he refused on the account that the land was uncultivable.[2] Instead, he was given all the land between the river Epte and the sea "in freehold and good money".[3] In addition, it granted him Brittany "for his livelihood."[3] At the time, Brittany was an independent country which present day France had unsuccessfully tried to conquer. In exchange, Rollo guaranteed the king his loyalty, which involved military assistance for the protection of the kingdom against other Vikings. One of the conditions for the Vikings after their loss was to convert. As a token of his goodwill, Rollo also agreed to be baptized and to marry Gisela, a presumed legitimate daughter of Charles.[4] The traité en forme at Saint Clair-Sur-Epte marked the beginning of Normandy as a state. Rollo refused to kiss Charles' foot to solidify the deal. Instead, he ordered one of his men to proceed with the ordeal. The warrior subsequently yanked the king's leg whilst he was standing and kissed it, causing Charles to topple onto the ground. [5]

Formation of Normandy

With Norse bands of settlers, composed of non-aristocratic lineages, there came multiple communities formed and a new political ethos that was not Frankish. The Norsemen ("Northmen") came to be known as Normans in French.[6] This identity formation was partly possible because the Norse were adapting indigenous culture, speaking French, renouncing paganism and converting to Christianity,[7] and intermarrying with the local population.[8]

The territory covered by the treaty corresponds to the northern part of today's Upper Normandy down to the Seine, but the territory of the Vikings would eventually extend west beyond the Seine to form the Duchy of Normandy, so named because of the Norsemen who ruled it. The treaty allowed these new settlements. But not all Vikings were welcome. And with the death of Alan I, King of Brittany, another group of Vikings occupied Brittany faced their own dispute. Around 937, Alan I's grandson Alan II returned from England to expel those Vikings from Brittany in a war that was concluded in 939. During this period the Cotentin Peninsula was lost by Brittany and gained by Normandy.

There would be a convergence between Franks and Normans within a few generations. Political marriages played an important role in cultivating alliances and cohesion; wives were often called "peace weavers." Charles the Simple created an alliance and a grant of rights to those Vikings seeking to settle in 918. While the Normans did adapt, adopt, and assimilate to Christianity, they did not necessarily adopt indigenous administration: "The creation of Norman power between first settlement and the mid-eleventh century is not primarily of assimilation to Carolingian forms, as those appear in the capitualaries.[9] Rather, the Normans "adhered longer than the Franks around them – to older forms of social organization," that the Franks were abandoning.

The Normans came close to being absorbed into a lower social strata in Frankish society had not a renewed wave of Viking raids occurred in the 960s. Over time, the frontiers of the duchy, based in kinship, expanded to the west.[10] "By the mid-eleventh century the descendants of the settlers formed the most disciplined and cooperative warrior society in Europe, capable of a communal effort in the conquest and subjugation of England that other regional political entities were incapable of."[11] The Duchy of Normandy achieved success under Duke Richard I, who forged valuable marriage alliances through his children: his son and heir Richard II married Judith of Brittany; one daughter Emma became Queen of England, Denmark and Norway through her marriages to Æthelred the Unready (1002–1016) and Cnut the Great (1017–1035); another daughter Hawise married Geoffrey I, Duke of Brittany; a third daughter Maud married Odo II, Count of Blois.

See also

References

- Francois Neveux. A Brief History of The Normans. Constable and Robinson Ltd. 2006; p. 62.

- Dudo of Saint-Quentin, The History of the Normans, trans. E. Christiansen (Woodbridge: Boydell , pp. 48–49)

- Bradbury "Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066: Model and evidences" Chapter 1-3

- Timothy Baker, The Normans New York: Macmillan, 1966.

- Dudo of Saint-Quentin, The History of the Normans, trans. E. Christiansen (Woodbridge: Boydell , p. 49)

- Crouch Normans pp. 15–16

- Bates Normandy Before 1066 p. 12

- Bates Normandy Before 1066 pp. 20–21

- Bradbury "Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066: Model and evidences" p. 1

- Hallam and Everard Capetian France p. 53

- Bradbury "Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066: Model and evidences" pp. 7–8