Spectacled bear

The spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), also known as the South American bear, Andean bear, Andean short-faced bear or mountain bear and locally as jukumari (Aymara and Quechua[3]), ukumari (Quechua) or ukuku, is a species of bear native to the Andes Mountains in northern and western South America. It is the only living species of bear native to South America, and the last remaining short-faced bear (subfamily Tremarctinae). Its closest relatives are the extinct Tremarctos floridanus,[4] and the giant short-faced bears (Arctodus and Arctotherium), which became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene around 12,000 years ago.[5][6] The diet of the spectacled bear is mostly herbivorous, but it occasionally engages in carnivorous behavior. The species is classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN because of habitat loss.

| Spectacled bear Temporal range: Late Pleistocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Genus: | Tremarctos |

| Species: | T. ornatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Tremarctos ornatus (Cuvier, 1825) | |

| |

| Spectacled bear range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ursus ornatus Cuvier, 1825 | |

Description

The spectacled bear is the only bear native to South America and is the largest land carnivore in that part of the world, although as little as 5% of its diet is composed of meat. Among South America's extant, native land animals, only the Baird's tapir, South American tapir and mountain tapir are heavier than the bear.[7]

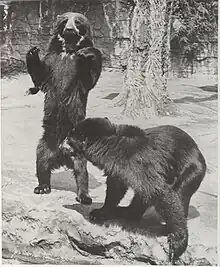

The spectacled bear is a mid-sized species of bear. Overall, its fur is blackish in colour, though bears may vary from jet black to dark brown and to even a reddish hue. The species typically has distinctive beige or ginger-coloured markings across its face and upper chest, though not all spectacled bears have "spectacle" markings. The pattern and extent of pale markings are slightly different on each individual bear, and bears can be readily distinguished by this.[8] Males are a third larger than females in dimensions and sometimes twice their weight.[9] Males can weigh from 100 to 200 kg (220 to 440 lb), and females can weigh from 35 to 82 kg (77 to 181 lb).[10] Head-and-body length can range from 120 to 200 cm (47 to 78.5 in), though mature males do not measure less than 150 cm (59 in).[11][12] On average males weigh about 115 kg (254 lb) and females average about 65 kg (143 lb), thus it rivals the polar bear for the most sexually dimorphic modern bear.[13][14] A male in captivity that was considered obese weighed 222.5 kg (491 lb).[15] The tail is a mere 7 cm (2.8 in) in length, and the shoulder height is from 60 to 90 cm (23.5 to 35.5 in). Compared to other living bears, this species has a more rounded face with a relatively short and broad snout. In some extinct species of the Tremarctinae subfamily, this facial structure has been thought to be an adaptation to a largely carnivorous diet, despite the modern spectacled bears' herbivorous dietary preferences.[16][17][18]

The spectacled bear's sense of smell is extremely sensitive. They can perceive from the ground when a tree is loaded with ripe fruit. On the other hand, their hearing is moderate and their vision is short.[19]

Distribution and habitat

Despite some rare spilling-over into eastern Panama,[20] spectacled bears are mostly restricted to certain areas of northern and western South America. They can range in western Venezuela,[21] Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, western Bolivia, and northwestern Argentina. Its elongated geographical distribution is only 200 to 650 km (120 to 400 mi) wide but with a length of more than 4,600 km (2,900 mi).[22]

The species is found almost entirely in the Andes Mountains. Before spectacled bear populations became fragmented during the last 500 years, the species had a reputation for being adaptable, as it is found in a wide variety of habitats and altitudes throughout its range, including cloud forests, high-altitude grasslands, dry forests and scrub deserts. A single spectacled bear population on the border of Peru and Ecuador inhabited as great a range of habitat types as the world's brown bears (Ursus arctos) now occupy.[12] The best habitats for spectacled bears are humid to very humid montane forests. These cloud forests typically occupy a 500 to 1,000 m (1,600 to 3,300 ft) elevational band between 1,000 and 2,700 m (3,300 and 8,900 ft) depending on latitude. Generally, the wetter these forests are the more food species there are that can support bears.[12][23] Occasionally, they may reach altitudes as low as 250 m (820 ft), but are not typically found below 1,900 m (6,200 ft) in the foothills. They can even range up to the mountain snow line at over 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in elevation.[7][12][24] Therefore, it is well known that bears use all these types of habitats in regional movements; however, the seasonal patterns of these movements are still unknown.[22]

Nowadays, the distribution area of the Tremarctos ornatus is influenced by the human presence, mainly due to habitat destruction and degradation, hunting and fragmentation of populations. This fragmentation is mainly found in Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Argentina. It represents several problems to this population because, first, their persistence is compromised if they are small, isolated populations, even without facing habitat lost or hunting. Second, the transformation of the landscape represents loss of availability of the type of habitats spectacled bears need. Third, fragmentation exposes bears to hunting and killing due to its accessibility.[22]

Naming and etymology

Tremarctos ornatus is commonly referred to in English as the "spectacled bear", a reference to the light colouring on its chest, neck and face, which may resemble spectacles in some individuals, or the "Andean bear" for its distribution along the Andes. The root trem- comes from a Greek word meaning "hole"; arctos is the Greek word for "bear". Tremarctos is a reference to an unusual hole on the animal's humerus. Ornatus, Latin for "decorated", is a reference to the markings that give the bear its common English name.[25]

Phylogeny

A 2007 investigation into the mitochondrial DNA of bear species indicates that the subfamily Tremarctinae, which includes the extant spectacled bear, diverged from the Ursinae subfamily approximately 5.7 million years ago.[26][27] Tremarctinae includes the extinct American giant short-faced and Florida short-faced bears.

Behaviour and diet

Spectacled bears are one of four extant bear species that are habitually arboreal, alongside the American black bear (Ursus americanus) and Asian black bear (U. thibetanus), and the sun bear (Helarctos malayanus). In Andean cloud forests, spectacled bears may be active both during the day and night, but specimens in the Peruvian desert are reported to bed down under vegetative cover during the day. Their continued survival alongside humans has depended mostly on their ability to climb even the tallest trees of the Andes. They usually retreat from the presence of humans, often by climbing trees.[28] Once up a tree, they may often build a platform, perhaps to aid in concealment, as well as to rest and store food on.[28] Although spectacled bears are solitary and tend to isolate themselves from one another to avoid competition, they are not territorial. They have even been recorded to feed in small groups at abundant food sources.[20] Males are reported to have an average home range of 23 km2 (8.9 sq mi) during the wet season and 27 km2 (10 sq mi) during the dry season. Females are reported to have an average home range of 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi) in the wet season and 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi) in the dry season.[29]

When encountered by humans or other spectacled bears, they will react in a docile but cautious manner, unless the intruder is seen as a threat or a mother's cubs are endangered. Like other bears, mothers are protective of their young and have attacked poachers. There is only a single reported human death due to a spectacled bear, which occurred while it was being hunted and was already shot. The only predators of cubs include cougars (Puma concolor) and possibly male spectacled bears. The bears "appear to avoid" jaguars, but the jaguar has considerably different habitat preferences, does not overlap with the spectacled bear in altitude on any specific mountain slope, and only overlaps slightly (900m) in altitude if the entire Cordillera Oriental is considered based upon unpublished data.[12] Generally, the only threat against adult bears is humans.[30] The longest-lived captive bear, at the National Zoo in Washington, DC, in the US, attained a lifespan of 36 years and 8 months. Lifespan in the wild has not been studied, but bears are believed to commonly live to 20 years or more unless they run foul of humans.[7]

Spectacled bears are more herbivorous than most other bears; normally about 5 to 7% of their diets is meat.[7] The most common foods for these bears include cactus, bromeliads (especially Puya ssp., Tillandsia ssp. and Guzmania ssp.) palm nuts, bamboo hearts, frailejon (Espeletia spp.), orchid bulbs, fallen fruit on the forest floor, unopened palm leaves, and moss.[31][32][33][34] They will also peel back tree bark to eat the nutritious second layer.[35] Much of this vegetation is very tough to open or digest for most animals, and the bear is one of the few species in its range to exploit these food sources. The spectacled bear has the largest zygomatic mandibular muscles relative to its body size and the shortest muzzle of any living bear, slightly surpassing the relative size of the giant panda's (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) morphology here.[36][37] Not coincidentally, both species are known for extensively consuming tough, fibrous plants. Unlike the ursid bears whose fourth premolar has a more well-developed protoconid, an adaptation for shearing flesh,[38] the fourth premolar of spectacled bears has blunt lophs with three pulp cavities instead of two, and can have three roots instead of the two that characterize ursid bears. The musculature and tooth characteristics are designed to support the stresses of grinding and crushing vegetation. Besides the giant panda, the spectacled bear is perhaps the most herbivorous living bear species.[39] These bears also eat agricultural products, such as sugarcane (Saccharum ssp.), honey (made by Apis ssp.), and maize (Zea mays), and have been known to travel above the tree line for berries and more ground-based bromeliads.[40] When food is abundant, such as large corn fields, up to nine individual bears have fed close by each other in a single vicinity.

Animal prey is usually quite small, but these bears can prey on adult deer, llama (Lama glama) and domestic cattle (Bos taurus) and horses (Equus caballus).[20][33][41] A spectacled bear was captured on a remote video-monitor predaceously attacking an adult mountain tapir perhaps nearly twice its own body mass, and adult horse and cattle killed by spectacled bears have been even heavier.[42] Animal prey has included rabbits, mice, other rodents, birds at the nest (especially ground-nesting birds like tinamous or lapwings (Vanellus ssp.), arthropods, and carrion.[31][32][43] They are occasionally accused of killing livestock, especially cattle, and raiding corn fields.[12][28] Allegedly, some bears become habituated to eating cattle, but the bears are actually more likely to eat cattle as carrion and some farmers may accidentally assume the spectacled bear killed them. Due to fear of loss of stock, bears may be killed on sight.[44][45]

Reproduction

.jpg.webp)

Most of the information available about the reproduction of this species has been through observation of captive animals.[46] In captivity, mating is concentrated in between February and September, according to the latitude,[46] and, in the wild, it has been seen how mating may occur at almost any time of the year, but activity normally peaks in April and June, at the beginning of the wet season and corresponding with the peak of fruit-ripening. The mating pair are together for one to two weeks, during which they will copulate multiple times for 12–45 minutes at a time. The courtship is based on games and non-aggressive fights while intercourse can be accompanied by loud sounds from both animals.[46]

In the wild, births usually occur in the dry season, between December and February but in captivity it occurs all year within the species' distribution.[46] The gestation period is 5.5 to 8.5 months.[7][12][47] From one to three cubs may be born, with four being rare and two being the average. The cubs are born with their eyes closed and weigh about 300 to 330 g (11 to 12 oz) each.[48] Although this species does not give birth during the hibernation cycle as do northern bear species, births usually occur in a small den and the female waits until the cubs can see and walk before she leaves with them, this occurs in between three and four months after birth.[46]

Females grow slower than males.[46] The size of the litter has been positively correlated with both the weight of the female and the abundance and variety of food sources, particularly the degree to which fruiting is temporally predictable.[12] The cubs often stay with the female for one year before striking out on their own.[7][12][20] This is related to the time mothers breastfeed (1 year), but keep providing maternal care for an additional year.[46] Breeding maturity is estimated to be reached at between four and seven years of age for both sexes, based solely on captive bears.[47] Females usually give birth for the first time when they are 5 years old and their fecundity is shorter than that of the males, who keep fertility almost all their lives.[46] Something that is in favor of the subsistence of the bear population is their longevity, since they are able to raise at least two cubs to adulthood, contributing to population replacement.[22] Wild bears can live for an average of 20 years.[49]

Conservation

Threats

The Andean bear is threatened due to poaching and habitat loss. Poaching might have several reasons: trophy hunting, pet trade, religious or magical beliefs, natural products trade and conflicts with humans.[50]

Trophy hunting of Andean bear was apparently popular during the 19th century in some rural areas of Latin-America. In the costumbrist novel María by Colombian writer Jorge Isaacs, it was portrayed as an activity for privileged young men in Colombia. Tales regarding pet bears are also known from documents about the Ecuadorian aristocracy of that time.[51] These threats might have diminished in recent years, but there are still isolated reports of captive bears confiscated in rural areas, which usually are unable to adapt again to their natural habitat and must be kept in zoological facilities.[52]

Religious or magical beliefs might be motivations for killing Andean bears, especially in places where bears are related to myths of disappearing women or children, or where bear parts are related to traditional medicine or superstitions. In this context, the trade of bear parts might have commercial value. Their gall bladders appear to be valued in traditional Chinese medicine and can fetch a high price on the international market. Conflicts with humans, however, appear to be the most common cause of poaching in large portions of its distribution.[50] Andean Bears are often suspected of attacking cattle and raiding crops, and are killed for retaliation or in order to avoid further damages. It has been argued that attacks to cattle attributed to Andean bear are partly due to other predators. Raiding of crops can be frequent in areas with diminishing natural resources and extensive crops in former bear habitat, or when problematic individuals get used to human environments.

The intensity of poaching can create ecological traps for Andean bears. That is, if bears are attracted to areas of high habitat quality that are also high in poaching risk.[53]

Perhaps the most epidemic problem for the species is extensive logging and farming, which has led to habitat loss for the largely tree-dependent bears. Shortage of natural food sources might push bears to feed on crops or livestock, increasing the conflict that usually results in poaching of individuals. Impacts of climate changes on bear habitat and food sources are not fully understood, but might have potential negative impact in the near future.

As stated, one of the major limitations to the viability of bear populations is human-caused mortality, mainly poaching and habitat loss; but the other big limitation is population size. Therefore, the most effective actions for their viability will be to increase population size and decrease poaching. For these actions to be effective, it is needed to understand where they are carried out, identifying areas where habitat protection and landscape management are realistically capable of maintaining large bear populations.[22]

Perception of the Andean bear

There are two views of the Andean Bears. One is ex-situ, people that live far from where the bears inhabit; for them, the spectacled bears are usually charismatic symbols of the wilderness, animals that are not aggressive and that are mainly vegetarians. The other view is in-situ, people that live in areas where the bears inhabit; for them, bears are cattle predators, pests that should be killed as a preventative measure and where any cattle loss is immediately attributed to them, becoming persecuted and hunted.[54]

Conservation actions and plans

The IUCN has recommended the following courses for spectacled bear conservation: expansion and implementation of conservation land to prevent further development, greater species level research and monitoring of trends and threats, more concerted management of current conservation areas, stewardship programs for bears which engage local residents and the education of the public regarding spectacled bears, especially the benefits of conserving the species due to its effect on natural resources.[12]

National governments, NGOs and rural communities have made different commitments to conservation of this species along its distribution. Conservation actions in Venezuela date back to the early 1990s, and have been based mostly on environmental education at several levels and the establishment of protected areas. The effort of several organisations has led to a widespread recognition of the Andean bear in Venezuelan society, raising it as an emblematic species of conservation efforts in the country, and to the establishment of a 10-year action plan.[55] Evidence regarding the objective effectiveness of these programs (like reducing poaching risk, maintaining population viability, and reducing extinction risk) is subject to debate and needs to be further evaluated.[56][57]

Legislation against bear hunting exists, but is rarely enforced.[50][58] This leads to persistence of the poaching problem, even inside protected areas.[53]

In 2006 the Spectacled Bear Conservation Society was established in Peru to study and protect the spectacled bear.[59]

Spectacled bear and protected areas

To evaluate the protected status of the Andean bears, back in 1998 researchers evaluated the percentage of their habitats included in national and protected areas. This evaluation showed that only 18.5% of the bear range was located in 58 protected areas, highlighting that many of them were small, especially those in the northern Andes. The largest park had an area of 2,050 km2 (790 sq mi) while the median size of 43 parks from Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador was 1,250 km2 (480 sq mi), which may result too small to maintain a sustainable bear population. Therefore, these researchers stated the importance of the creation of habitat blocks outside protected areas since they might provide opportunities for the protection of these animals.[22]

Other suggested conservation strategies

Researchers suggest the following spectacled bear conservation strategies:[60]

- Protect high-quality habitats while maintaining connectivity between their different elevational zones. In reality, it is not possible to manage all the undisturbed habitat the bears need in the long term, so it is important to identify those high-quality habitats that maximize biodiversity gain.

- Alleviate human-bear conflicts through conflict management, thinking about the spatial configuration of this animal habitat.

- Mitigate human impacts on protected areas through the design of comprehensive management strategies.

- Sustain landscape diversity in the bear conservation study areas to ensure them food and seasonal access to resources in all the habitats they frequent.

- Maintain bear population connectivity, emphasizing those conservation areas that connect different ecosystems, such as the cloud forest and the paramo.

- Rethink roads: where they are built, how and with what purpose, understanding that they define the macro configuration of bear habitat and are a barrier for bear movements and population connectivity.

- Integrate hydrological criteria at a landscape scale will benefit bears and other biotic communities that associate with aquatic environments, including humans. Linking bear habitat conservation and water management can be effective for the development of conservation strategies that benefit all.

- In places where it is almost impossible to establish new protected areas due mainly to the fact that many people already live in the area, the creation of natural corridors is possibly the best tool for the conservation of species with migratory patterns such as the endangered Andean bear.

Spectacled bear in Ecuador

Spectacled bears in Ecuador live in approximately 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi) of paramo and cloud forest habitats. About one-third of this area is part of the National System of Protected Areas and the remaining 67% is located on unprotected, undeveloped areas that have suffered a substantial reduction of approximately 40% from its original distribution.[60]

Due to this land-use conversion to agricultural uses, important amounts of the spectacled bear habitat have been lost, which has fragmented their territory and isolated populations to small areas that might result in extirpations in the long term. Therefore, the distribution of the species in the country is set in numerous habitat patches, from which many are small.[60]

In popular culture

- The children's character Paddington Bear is a spectacled bear from Peru.[61]

References

- Velez-Liendo, X.; García-Rangel, S. (2018) [errata version of 2017 assessment]. "Tremarctos ornatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22066A123792952. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22066A45034047.en. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Sichra, Inge (2003). La vitalidad del quechua: lengua y sociedad en dos provincias de Cochabamba (in Spanish). Plural editores. p. 121. ISBN 978-99905-75-14-9.

- Krause, J.; Unger, T.; Noçon, A.; Malaspinas, A.; Kolokotronis, S.; Stiller, M.; Soibelzon, L.; Spriggs, H.; Dear, P. H.; Briggs, A. W.; Bray, S. C. E.; O'Brien, S. J.; Rabeder, G.; Matheus, P.; Cooper, A.; Slatkin, M.; Pääbo, S.; Hofreiter, M. (2008). "Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (220): 220. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220. PMC 2518930. PMID 18662376.

- Spectacled Bear. Grizzly Bear.org. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Spectacled Bears. Bear Planet. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Nowak, R.M. (1991). Walker's Mammals of the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, ISBN 0801857899.

- Roth H.H. (1964). "Ein beitrag zur Kenntnis von Tremarctos ornatus (Cuvier)". D. Zoolog. Garten. 29: 107–129.

- Brown, Gary (1996). Great Bear Almanac. Lyons & Burford. p. 340. ISBN 1-55821-474-7.

- Spectacled, or Andean, Bear – National Zoo| FONZ Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine. Nationalzoo.si.edu. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Macdonald, D. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Servheen, C., Herrero, S. and Peyton, B. (1999). Bears: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Bear and Polar Bear Specialist Groups, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Soibelzon, L. H., & Tarantini, V. B. (2009). Estimación de la masa corporal de las especies de osos fósiles y actuales (Ursidae, Tremarctinae) de América del Sur. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, 11(2), 243-254.

- Bruijnzeel, L. A., Scatena, F. N., & Hamilton, L. S. (Eds.). (2011). Tropical montane cloud forests: science for conservation and management. Cambridge University Press.

- Lisi, K. J., Barnes, T. L., & Edwards, M. S. (2013). Bear weight management: a diet reduction plan for an obese spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus). Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 1(2), 81.

- Spectacled bear videos, photos and facts – Tremarctos ornatus Archived 2011-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. ARKive. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Spectacled Bear. Brazilianfauna.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (1970). The international wildlife encyclopedia. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 2470–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7266-7. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Castellanos, A., Altamirano, M., Tapia, G. (2005). Ecología y comportamiento de osos andinos reintroducidos en la Reserva Biológica Maquipucuna, Ecuador: implicaciones en la conservación. Politécnica, 26 (1) Biología 6: pp-pp, 2005. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Armando_Castellanos/publication/237011243_Ecologia_y_Comportamiento_de_Osos_Andinos_Reintroducidos_en_la_Reserva_Biologica_Maquipucuna_Ecuador_Implicaciones_en_Conservacion/links/0c96051ae54b8ef3f0000000/Ecologia-y-Comportamiento-de-Osos-Andinos-Reintroducidos-en-la-Reserva-Biologica-Maquipucuna-Ecuador-Implicaciones-en-Conservacion.pdf

- Bunnell, Fred (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 96. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- "Spectacled bear, Andean bear, ucumari". BBC – Science & Nature – Wildfacts. BBC. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- Kattan, Gustavo; Hernández, Olga Lucía; Goldstein, Isaac; Rojas, Vladimir; Murillo, Oscar; Gómez, Carolina; Restrepo, Héctor; Cuesta, Francisco (2004). "Range fragmentation in the spectacled bear Tremarctos ornatus in the northern Andes". Oryx. 38 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1017/S0030605304000298. ISSN 0030-6053.

- Peyton, B. (1987). "Habitat components of the spectacled bear". Ursus. 7 (International Conf. Bear Res. and Manage): 127–133.

- Brown, A.D. and Rumiz, D.I. (1989). "Habitat and distribution of the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) in the southern limit of its range", pp. 93–103. in: M. Rosenthal (ed.) Proc. First Int. Symp. Spectacled Bear. Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens, Chicago Park District Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

- "Tremarctos rnatus". Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Krause, Unger (2008). "Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8: 220. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220. PMC 2518930. PMID 18662376.

- Yu, Li (2007). "Analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences increases phylogenetic resolution of bears (Ursidae), a mammalian family that experienced rapid speciation". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 198. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-198. PMC 2151078. PMID 17956639.

- LaFee, Scott (2009-09-07). "Hanging on, bearly: South America's only bear species struggles to avoid extinction". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2009-11-07. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- Hunter, Luke (2011) Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691152288

- Spectacled Bear Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine. rosamondgiffordzoo.org

- Peyton, B. (1980). "Ecology, distribution, and food habits of spectacled bears, Tremarctos ornatus, in Peru". Journal of Mammalogy. 61 (4): 639–652. doi:10.2307/1380309. JSTOR 1380309.

- Jorgenson, J.P., and Rodriguez, J.S. (1986). Proyecto del oso frontino en Colombia. Spectacled Bear Specialist Group Newsletter 10:22–25.

- Goldstein, I. (1989). "Spectacled bear distribution and diet in the Venezuelan Andes", pp. 2–16. in: Rosenthal, M., (Ed.) Proc. First Int. Symp. Spectacled Bear. Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens, Chicago Park District Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

- "Tremarctos ornatus (Spectacled bear)". Animal Diversity Web.

- Figueroa, J. and Stucchi, M. (2009). El Oso Andino: Alcances Sobre su Historia Natural. Asociación para la Investigación y Conservación de la Biodiversidad-AICB, Lima, Peru.

- Davis, D.D. (1955). "Masticatory apparatus in the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus)". Fieldiana Zoology. 37: 25–46. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.2809.

- Mondolfi E (1971). "El oso frontino". Defensa de la Naturaleza. 1: 31–35.

- Kurtén, B. (1966). "Pleistocene bears of North America: Genus Tremarctos, spectacled bears". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 115: 1–96.

- Thenius, E. (1976). "Zur stammesgeschichtlichen Herkunft von Tremarctos (Ursidae, Mammalia)". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 41: 109–114.

- Suárez, L. (1989). "Seasonal distribution and food habits of the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) in the highlands of Ecuador". Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment. 23 (3): 133–136. doi:10.1080/01650528809360755.

- Spectacled bear Tremarctos ornatus – Natural Diet (Literature Reports) Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine. Wildlife1.wildlifeinformation.org. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Rodriguez, A., Gomez, R., Moreno, A., Cuellar, C., & Lizcano, D. J. (2014). Record of a mountain tapir attacked by an Andean bear on a camera trap. Tapir Conservation, 23, 24-25.

- Spectacled Bears. Bears Of The World. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- Peru: Who We Are Archived 2011-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Spectacled Bear Conservation. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- CARNIVORA – Spectacled Bear – Tremarctos ornatus Archived 2010-11-20 at the Wayback Machine. Carnivoraforum.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-26.

- García-Rangel, Shaenandhoa (2012). "Andean bear Tremarctos ornatus natural history and conservation: Andean bear natural history and conservation". Mammal Review. 42 (2): 85–119. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00207.x.

- Rosenthal, M.A. (1987). "Biological management of spectacled bears (Tremarctos ornatus) in captivity", pp. 93–103. in: Weinhardt, D., (ed.) International studybook for the spectacled bear, 1986. Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens, Chicago Park District Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

- Bloxam, Q. (1977). "Breeding the Spectacled bear Tremarctos ornatus at Jersey Zoo". International Zoo Yearbook. 17: 158–161. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1977.tb00894.x.

- Fenner, Kesley. "Tremarctos ornatus (spectacled bear)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2022-12-21.

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Ferrer-Paris, J. R.; Yerena, E.; García-Rangel, S.; Rodríguez-Clark, K. M. (2008). "Factors affecting poaching risk to Vulnerable Andean bears Tremarctos ornatus in the Cordillera de Mérida, Venezuela: space, parks and people". Oryx. 42 (3): 437–447. doi:10.1017/S0030605308006996.

- Boussingault, Jean Baptiste Joseph Dieudonné (2005). Memoirs. p. Capítulo XII El Salto de Tequendama – Historia de Manuelita Sáenz. Archived from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- Rodríguez-Clark, K. M.; Sánchez-Mercado, A. (2006). "Population management of threatened taxa in captivity within their natural ranges: Lessons from Andean bears (Tremarctos ornatus) in Venezuela". Biological Conservation. 129 (1): 134–148. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.10.037.

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Ferrer-Paris, J. R.; García-Rangel, S.; Yerena, E.; Robertson, B. A.; Rodríguez-Clark, K. M. (2014). "Combining threat and occurrence models to predict potential ecological traps for Andean bears in the Cordillera de Mérida, Venezuela". Animal Conservation. 17 (4): 388–398. doi:10.1111/acv.12106. S2CID 83556460.

- Goldstein, Isaac; Paisley, Susanna; Wallace, Robert; Jorgenson, Jeffrey P.; Cuesta, Francisco; Castellanos, Armando (2006). "Andean bear–livestock conflicts: a review". Ursus. 17 (1): 8–15. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2006)17[8:abcar]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1537-6176. S2CID 55185188.

- Edgard Yerena; Dorixa Monsalve Dam; Denis Alexander Torres; Ada Sánchez; Shaenandhoa García-Rangel; Andrés Eloy Bracho; Zoila Martínez; Isis Gómez (2007). Plan de Acción para la Conservación del Oso Andino (Tremarctos ornatus) en Venezuela (2006-2016). Fundación AndígenA, FUDENA, Universidad Simón Bolívar. p. 60pp.

- D. Monsalve-Dam; A Sánchez-Mercado; E. Yerena; S. García-Rangel; D. Torres (2010). "Efectividad de las áreas protegidas para la conservación del oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) en los Andes Suramericanos". Ciencia y Conservación de Especies Amenazadas en Venezuela: Conservación Basada en Evidencias e Intervenciones Estratégicas. Provita: 127–136.

- A. Sánchez-Mercado; E. Yerena; D. Monsalve; S. García-Rangel; D. Torres (2010). "Efectividad de las iniciativas de educación ambiental para la conservación del oso andino (Tremarctos ornatus) en la cordillera andina". Ciencia y Conservación de Especies Amenazadas en Venezuela: Conservación Basada en Evidencias e Intervenciones Estratégicas. Provita: 137–146.

- "Endangered Bears", The Pet Wiki.

- "Spectacled Bear Conservation Society - Peru". Spectacled Bear Conservation Society.

- Peralvo, Manuel F.; Cuesta, Francisco; van Manen, Frank (2005). "Delineating priority habitat areas for the conservation of Andean bears in northern Ecuador". Ursus. 16 (2): 222–233. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2005)016[0222:dphaft]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1537-6176. S2CID 86289594.

- Alice Vincent (10 Jun 2014). "Paddington Bear: 13 things you didn't know". www.telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

It's surprising that the earnest little chap wasn't given glasses. Bond wanted to Paddington to have 'travelled all the way from darkest Africa', but was advised by his agent to change his country of origin due to the lack of bears in Africa. Instead, he picked Peru - home to the Spectacled Bear.