Trial of Mary Fitzpatrick

The trial of Mary Fitzpatrick of November 1882, before Justice Henry Hawkins, was an English murder and robbery case at the York Winter Assizes in the assize courts at York Castle, which drew much attention in contemporary newspapers. It followed the death of 24-year-old glass blower James Richardson, who was last seen alive in the company of rag sorter Mary Fitzpatrick,[1] aged 23, and was next seen dead in the water without his watch and chain. The Coroner's Court returned a verdict of "wilful murder."

| Crown vs Mary Fitzpatrick | |

|---|---|

| Court | York Winter Assizes |

| Decided | 11 November 1882 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | Charges: Wilful murder Robbery with violence |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Sir Henry Hawkins JP |

| Keywords | |

| Robbery Penal servitude Six years | |

Fitzpatrick and Richardson lived in slum areas of Leeds; Fitzpatrick was tried by at least five aristocrats.[1] She was convicted of robbery, and sentenced to penal servitude for six years. At the time of the trial she had two young children.

Mary Fitzpatrick, perpetrator

Mary Fitzpatrick (b.1855–1859) née Corcoran, alias Mary Anne Gollagher, was born in Leeds, West Riding of Yorkshire, England.[nb 1] She was the daughter of Richard Corcoran (b.ca.1829) a greengrocer and labourer, and his wife Catherine née Connor (b.ca.1832), both from County Mayo.[2] Richard and Catherine married in Leeds in 1850.[3] in 1851 the young couple were living at 8 Dufton's Yard with a number of Irish lodgers.[nb 2][4] They were "respectable" Roman Catholics and "migrants from famine-torn Ireland ... a poor family struggling to make ends meet."[2] They were living at 162 York Street, Leeds in 1861,[5] and at 72 York Street in 1876.[6]

Mary's younger siblings were: Amy (b.ca.1865), and Michael (b.ca.1868).[7] The 1881 Census shows Mary's parents Richard and Catherine living at 15 Orange Street;[nb 3] Richard had lost his greengrocer trade and been a labourer since before 1851.[8] By 1876 he was a hawker.[6] The yards inhabited by the Corcoran family were ginnels or alleys inside the slum area around the edge of Quarry Hill.[9] They were living in the Quarry Hill area, where at that time, many houses had "no piped water supply or proper sewerage system ... Sometimes there weren't even any ... outside toilets; people used a bucket which could be emptied on a common midden."[10]

Mary was attending school by the age of six years, so that she was sufficiently literate to sign her marriage certificate.[5][6] By the time she was 15 years old, she was working as a mill hand, "a hard and dangerous job for a child." Mary and her family had no recorded offences before Mary married.[2][7] She married Irish iron puddler Thomas Fitzpatrick (b.ca.1857), son of flour miller Patrick Fitzpatrick, at St Patrick's Chapel, York Road, Leeds, on 1 May 1876.[6][11] They had two children, one named John (b.ca.1876), and in 1881 the Fitzpatrick family was boarding at New Yard, Workington, Cumberland.[2][12] By the time of her 1882 trial, Mary was living in Lemon Street, Quarry Hill, and was separated from her husband,[1][13] who had emigrated to America amid the negative pre-trial publicity.[2]

.JPG.webp) Mary Fitzpatrick, 1880s

Mary Fitzpatrick, 1880s Former Dufton's Yard, where Mary's parents lived in 1851

Former Dufton's Yard, where Mary's parents lived in 1851.jpg.webp) Former Lemon Street, where Fitzpatrick lived in 1882

Former Lemon Street, where Fitzpatrick lived in 1882

Fitzpatrick's criminal record

After Mary's children were born, she began drinking. In 1879 she was sentenced to seven days' imprisonment for riotousness, and then to four months and two months for stealing flannel and handkerchiefs respectively.[2] On Thursday 10 June 1880 at Dewsbury Borough Court, three young women, including one Mary Fitzpatrick, were charged by the Mayor, Alderman John Bates, with obstructing a footpath at 6.30pm on 3 June, in School Road, Daw Green. Fitzpatrick was fined 5 shillings and costs.[14] Under the name of Corcoran, on 21 June 1880 at York, she was convicted of felony.[15] She was committed to two months imprisonment for stealing a scarf and hat. After being released, she was then caught under a bed at the scene of a robbery, however she was not convicted on that occasion. She was placed under police supervision, and apprehended again in September of the same year as a "suspect person". She remained out of prison for a year or more, but her marriage had broken up by 1881.[2] At her 1882 trial, the judge said that she had already been convicted of three felonies in total,[15] and the Derby Daily Telegraph reported that Fitzpatrick had a "loose character".[16]

James Richardson, victim

James Richardson's father was Charles Richardson (Hunslet ca.1819 – Hunslet Carr 8 June 1880),[17] a coal miner who eventually died of tuberculosis, and his mother was Mary Richardson née Howden (b. Hunslet ca.1820) who managed a grocery shop and was illiterate.[18][19] Charles and Mary married in Leeds in 1838.[20] Between 1861 and 1871, the family lived at 31 Balm Lane, Hunslet, and then at least from 1881 at Taylor's Place, Low Road, Hunslet Carr.[19][21][22]

Richardson (Hunslet 16 July 1858 – Hunslet 15 August 1882), born at 3 Carr Place, Hunslet,[18] was the youngest of eight siblings. They were William (b.ca.1839) a coal miner and later a broker, Elizabeth (b.ca.1843) a flax spinner, John (b.ca.1844) a coal miner, Mary (b.ca.1847) a flax spinner, Charles (b.ca.1849) a brick maker, and Emily (b.ca.1854) and Sarah (b.ca.1856), both flax spinners.[19][21][22]

Richardson was a glass blower,[16] or glass bottle maker, most likely an employee of Alfred Alexander & co., Hunslet Glass Works, in South Accommodation Road.[19][21][22] He was 24 years old when he died.[23]

.jpg.webp) This ginnel is the former Taylor's Place, home of the Richardson family, 1882.

This ginnel is the former Taylor's Place, home of the Richardson family, 1882. Taylor's Place, off Low Road, Hunslet

Taylor's Place, off Low Road, Hunslet

Background to alleged crime

Richardson's "drunken state"

Richardson's mother Mary last saw him between eleven and twelve o'clock midday on the day of the Hunslet Feast, Tuesday 15 August 1882, when he "left home in company with a young man named James Ramsden", and his elder brother William saw him wearing his silver watch and gold Albert chain on the afternoon of that day, at the Feast. At that time, the Feast was on Penny Hill, adjacent to St Mary's Church in Hunslet.[13] Richardson "spent his time in going from one public-house to another, the result being that in the evening he was in a very drunken state."[15] The glass blower Benjamin Ryan (b.ca.1857) was a colleague of James, and an erstwhile boarder with his family.[22] He saw Richardson on the night of 15 August. "He left him at the Exchange Inn, about ten minutes to ten, when the deceased was drunk. [Ryan] wanted to take his watch and guard for safety, but the deceased refused to give them to him."[13]

Last known movements of victim

Richardson and Fitzpatrick were seen at two public houses together.[24] When Ryan saw them, [Fitzpatrick], who seemed to be sober, was standing at the bar of the taps in the [Exchange] public house," a place for working class men only at that time.[13] "At ten minutes to ten ... [James] was alone, and [Fitzpatrick] was standing at the counter. She appeared to be sober, and in [Ryan's] opinion, did not know Richardson." This might raise the question of whether Fitzpatrick was not in the inn for fun, but was planning to follow a selected stranger with a view to theft.[25]

Fitzpatrick was seen drinking alongside Richardson later that evening.[16] By ten-thirty, Richardson and Fitzpatrick were spotted by a public house waiter, Samuel Holdsworth, "standing together in the passage of the George IV inn. Both of them were drinking (the former being the worse for liquor), but they did not speak to one another. When [Richardson] left the house, [Fitzpatrick] followed him. He saw both of them walking together along Church Street, and saw [Fitzpatrick] take hold of [Richardson's] arm,[13] because he was "walking unsteadily."[25] They were walking in the direction of the Hunslet Old Mill Dam.[24] Richardson's brother William last saw him at 11.30 p.m. that night in Balm Street, where they had lived as children.[nb 4][25] James Richardson was never seen alive again after the night of 15 August,[1] and Fitzpatrick was the last person to see him alive.[2]

Death of victim, and robbery

.JPG.webp)

Richardson died between Tuesday 15 August which was the night of Hunslet Feast, and the following Saturday.[1] His body was found on Saturday 19 August 1882 in the Old Mill Dam near Hunslet Old Mill.[24] He had died before his body entered the water. [25]

Richardson's watch and chain

The body of James Richardson was found on Saturday 19 August in the Old Mill Dam on the River Aire at Hunslet Carr.[1][13] Fitzpatrick was found either in possession of Richardson's watch and chain, or it was still with the pawnbroker Thornton of Kirkgate, Leeds.[16] Either way, after being caught, she said that Richardson had given the watch to her.[15][2] It would later be alleged that after the death of Richardson, Fitzpatrick "pawned a watch and guard,[2] and finger ring belonging to him."[1] Fitzpatrick had pledged the gold chain at Thornton's on Saturday 19 August, "which she asked an advance of 5s. She stated that her husband had pawned the guard several times for £2 10s, but she only wanted a few shillings to make some small purchases. She pledged it for 5s in the name of Mary Mochan of 4, Spring Street, and said her husband's name was Thomas Mochan. She was accompanied by another woman." On Monday 21 August, an unknown person pawned Richardson's watch at the same pawn shop. "The next morning [Fitzpatrick] again went to the shop and obtained a further advance of 18s on the chain, stating that her husband had been locked up and fined."[13] Fitzpatrick knew that the chain was solid gold.[25]

Richardson's brother William, now a broker, identified the pawned silver lever watch and gold chain as James Richardson's; he "produced a hand-book belonging to his brother, containing the number of the watch." The body was without the watch and chain, and without Richardson's gold ring and silk handkerchief when it was viewed at the Wellington Inn, Hunslet.[13]

Remand

Fitzpatrick is apprehended

On being taken into custody, Fitzpatrick asked: "What am I going to be charged with?"[15] revealing that she "evidently knew something of Richardson's demise."[2] She then absconded, thus increasing suspicion of her guilt,[25] and was apprehended by Detective Easby in Hull on Saturday 9 September 1882. At Leeds, Fitzpatrick was indicted for wilful murder and robbery. Messrs Mellor and Banks were Counsel for the prosecution, and Vernon Blackburn was Counsel for the defence. "With considerable emotion," she pleaded not guilty.[15] On Monday 11 September she was charged at Leeds Police Court in Leeds Town Hall before Mr Bruce with wilful murder and theft.[2] After hearing witness statements, the Court ordered that she be remanded for another week for further collection of evidence.[13] Mary was remanded in custody on 11 September 1882 on a charge of robbery with violence, and murder.[16][1] Another report said that she was indicted for "having wilfully caused the death."[1] On Monday 18 September she was back in the Town Hall, and charged on remand with wilful murder and stealing the deceased's property.[26] On 20 September 1882, Fitzpatrick was charged on remand at Leeds Town Hall, firstly with wilful murder, and secondly with stealing and pawning a watch and guard.[27] At the inquest held at the Wellington Inn, Hunslet on Thursday 26 September 1882, the Leeds borough coroner found "injuries to the head" and returned a verdict of wilful murder.[23][28]

Trial

Fitzpatrick was removed from Armley Gaol on 3 November 1882,[29] and her trial, on the capital charge of wilful murder,[27] began on Saturday 4 November 1882 at the Yorkshire Winter Assizes in the assize courts at York Castle, with the Grand Jury being sworn in at York Guildhall. The judge was Sir Henry Hawkins JP who, having presided over numerous murder trials, was known as Hanging Hawkins.[30][31][32] He processed to York Minster where he was met by the Dean of York, clerics and choristers, and an organ voluntary was played as they all moved up the aisle. Then, fully robed, he processed to York Castle in the state carriage of the High Sheriff of Yorkshire Sir Henry Day Ingilby of Ripley Castle, "accompanied by the High Sheriff and the High Sheriff's chaplain ... attended by the usual retinue of trumpeters and halbertmen" in livery.[30] Hawkins was joined on the bench by Ingilby. The jury's foreman was Sir William Cayley Worsley, Baronet, of Hovingham Hall. The jury also included at least five aristocrats: the Honourable Reginald Parker of Askham Hall in Askham Bryan, the Hon. Payan Dawnay of Beningbrough Hall, the Hon. Miles Stapleton of Carlton Towers, Sir Reginald Graham, Baronet, of Norton Conyers House and Sir Henry Monson de la Poer Beresford Peirse, Baronet, of Bedale Hall.[1]

Sir Henry Hawkins JP

Sir Henry Hawkins JP Sheriff's state coach, with halberdmen and trumpeters, like the one used by Hawkins

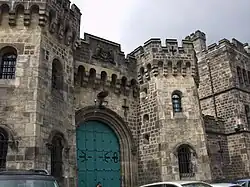

Sheriff's state coach, with halberdmen and trumpeters, like the one used by Hawkins.jpg.webp) Former Assize building at York Castle

Former Assize building at York Castle

Court findings

Beforehand, the judge informed the jury that he expected them to give a true bill, or clear indictment, in all cases on that day.[1] On Monday 6 November, a true bill for wilful murder had been returned against Fitzpatrick at the Yorkshire Assizes.[33] However, when the case resumed on Saturday 11 November, Judge Hawkins said that, "he could not say there was no evidence for the jury, but it was by no means so strong as in many cases. There was however the evidence that prisoner was last seen in the deceased's company, and that she had his watch." The jury found the prisoner not guilty of murder, but found her guilty of "stealing from the person."[15][2]

Sentence

When sentencing Fitzpatrick, Justice Hawkins commented as follows:[15]

"The prisoner had been convicted of the most daring and impudent robbery. That she stole the watch the jury were satisfied, but how much violence she applied was not shown. He (his lordship) was satisfied that she stole it. If she had never been in trouble of this sort before he would have passed a different sentence than he was about to pass. He found that not only was the prisoner leading the life of a common person, and walking about the streets and drinking with men, but on three different occasions she had been convicted of felony. Under these circumstances it would be idle for him to pass a sentence upon the prisoner that he would on an ordinary woman. There was no crime that required more suppressing than that of robbing from the person in the public streets. It should be put down with a strong hand."[15]

Fitzpatrick was sentenced to penal servitude for six years. As the guards took her away, she called out to the gallery, "Father!" and, "Oh dear, oh dear, I never stole the watch and guard."[15][2]

Imprisonment and later life

It is not known where Fitzpatrick served her sentence, but she only served four years. She wrote home from prison, and to her husband and others, with "protestations of innocence." After three years she was eligible for release on licence, and in 1886 was transferred from jail to the East End Refuge, Fulham. Her parents had left Leeds, so at the age of 30 years, around 1889, with the help of a charity she travelled to America to rejoin her husband. Nothing is known of her life after that.[2]

Notes

- According to the GRO index, there were four Mary Corcorans born in Leeds between 1855 and 1859, and we have no citation for a more precise date

- Dufton's Yard was adjacent to 17 Marsh Lane on the east side of Quarry Hill

- Orange Street was a yard adjacent to 57 York Street, in the Quarry Hill area of Leeds

- This evidence of Richardson's last movements does not match the rest, because it places his last-seen action at 11.30 p.m. as going away from the Mill Dam

References

- "The charge". York Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 6 November 1882. p. 6 col3. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Williams, Lucy (2018). Criminal Women, 1850–1920: Researching the Lives of Britain's Female Offenders. Grub Street Publishers, Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1526718617. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 1 September 2019. Marriages Jun 1850 Conner Catherine and Richard Corcoran Leeds XXIII 541

- 1851 England Census 2320/676 p40

- 1861 England Census 3380/85/p.2

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 21 August 2019. Marriages Jun 1876 Fitz Patrick Thomas Leeds 9b 742a. The marriage certificate says: First May 1876 at St Patrick's Chapel (Roman Catholic), York Road, Leeds, Thomas Fitzpatrick bachelor and puddler 19 years, son of flour miller Patrick Fitzpatrick, of Craven Street Leeds, and Mary Corcoran spinster 20 years, daughter of hawker Richard Corcoran, of 72 York Street Leeds. Both signed the register; witnesses were John Hall and Mary Ryan.

- 1871 England Census 4554/41/p.7

- 1881 England Census 4519/56 p.7

- Sheerin, Joseph (12 September 2014). "Leeds Streets that Have Completely Disappeared". Leeds List. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Discovering Leeds, poverty and riches: the working classes". Leodis. Leeds City Council. 2003. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "St Patrick's Chapel, York Road". Leeds Indexers. 2003. Retrieved 2 September 2019. St Patrick's Chapel was completed in 1832, on the north side of Quarry Hill; by 1893 it had been converted as part of St Patrick's School.

- 1881 England Census 5178/136 p.36

- "Alleged murder by a woman at Leeds". Hull Packet. British Newspaper Archive. 15 September 1882. p. 5 col6. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Obstructing a footpath". Dewsbury Reporter. British Newspaper Archive. 12 June 1880. p. 3 col3. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Alleged wilful murder and robbery at Leeds". York Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 11 November 1882. p. 6 col6. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Murder by a woman in Leeds". Derby Daily Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 12 September 1882. p. 4 col2. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 19 August 2019. Deaths Jun 1880 Richardson Charles 62 Hunslet 9b 193. The death certificate says: Eighth June 1880 Hunslet Carr, Charles Richardson, male, 62 years, coal miner, phthisis. (Informant) W Richardson, son, present at death, Hunslet Carr, Hunslet. Registered ninth June 1880.

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 19 August 2019. Births Sep 1858 Richardson James Hunslet 9b 258. His birth certificate says: "Sixteenth July 1858 (at) 13 Carr Place, James, boy, (father) Charles Richardson, (mother) Mary Richardson fermerly Howden, (father's occupation) coal miner, (informant) X the mark of Mary Richardson mother 13 Carr Place Hunslet, (registered) nineteenth July 1838." Note the date error on the certificate. The death certificate and trial reports confirm year of birth as 1858.

- 1861 England Census 73/3367/32/p.12

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 1 September 2019. Marriages Sep 1838 Richardson Charles and Howden Mary Leeds 23 322

- 1871 England Census 83/4512/37/p.16

- 1881 England Census 18/4487/156/p.27

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 19 August 2019. Deaths Sep 1882 Richardson James 24 Hunslet 9b 200. The death certificate says: 1882 19 August found in the River Aire near the old dam, Hunslet. James Richardson, male, 24 years, glass bottle maker, Taylor Place, Hunslet Carr. Injuries to the head, wilful murder by some persons or persons unknown. Certificate received from John C. Malcolm, Coroner for Leeds Inquest, held 21 August and adjourned to the 4, 12 and 26 September 1882. (Registered) twenty-eighth September 1882.

- "Alleged murder at Leeds". Yorkshire Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 18 November 1882. p. 3 col4. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Alleged murder at Leeds". Leeds Times. British Newspaper Archive. 16 September 1882. p. 2 col4. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "The alleged murder in Leeds". York Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 19 September 1882. p. 3 col6. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "The alleged murder by a woman in Leeds". Sheffield Independent. British Newspaper Archive. 21 September 1882. p. 3 col6. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "A verdict of wilful murder". Leeds Times. British Newspaper Archive. 30 September 1882. p. 3 col3. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Winter Assize County no..3". Yorkshire Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 28 October 1882. p. 1 col3. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Yorkshire Assizes". York Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 4 November 1882. p. 3 col5. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Jones, Catherine (26 August 2013). "St George's Hall judge Sir Henry Hawkins". Liverpool Echo. The Trust Project. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Stephen, Herbert (1912). "Hawkins, Henry". Dictionary of National Biography, 1912 supplement. p. 228.

- "Rowland Soer Smith". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 7 November 1882. p. 4 col4. Retrieved 19 August 2019.