Trichodina

Trichodina is a genus of ciliate alveolates that is ectocommensal or parasitic on aquatic animals, particularly fish. They are characterised by the presence of a ring of interlocking cytoskeletal denticles, which provide support for the cell and allow for adhesion to surfaces including fish tissue.

| Trichodina | |

|---|---|

| |

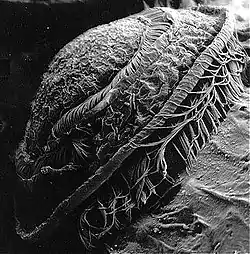

| Scanning electron micrograph of Trichodina on the gills of a mullet | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Trichodina Ehrenberg, 1831 |

Taxonomy

Trichodinids are members of the peritrichous ciliates, a paraphyletic group within the Oligohymenophorea. Specifically, they are mobiline peritrichs because they are capable of locomotion, as opposed to sessiline peritrichs such as Vorticella and Epistylis, which adhere to the substrate via a stalk or lorica. There are over 150 species in the genus Trichodina. Trichodinella, Tripartiella, Hemitrichodina, Paratrichodina and Vauchomia are similar genera.

Morphology

Trichodinids are round ciliates that may be disc-shaped or hemispherical. The cytostome (cell mouth) is on the surface that faces away from the host; this is termed the oral surface. The other side, or aboral surface, attaches to the skin of the host or other substrate. There is a spiral of cilia leading towards the cytostome and several rings of cilia at the periphery of the cell, responsible for creating adhesive suction and locomotory power. In the taxonomy of trichodinids, the exact number, shape and arrangement of the cytoskeletal denticles is critical for determining taxonomic relationships. These characters are usually revealed by silver nitrate staining of microscope slides, which stains the cell cytoplasm black and leaves the denticles white.

Life history

Trichodinids have a simple direct life cycle. That is, they have a single host and do not use alternation of generations or mass asexual replication off the host. They reproduce by binary fission, literally cell-splitting. This produces daughter cells with half the number of denticles of the parent cell. The full complement of denticles is restored by synthesis of new denticles from the outer edge of the cell, working inwards.

Trichodinids are typically found on the gills, skin and fins of fishes, though some species parasitise the urogenital system. A range of invertebrates is also host to trichodinid infections, including the surfaces of copepods and the mantle cavity of molluscs. Transmission occurs by direct contact of infected and uninfected hosts, and also by active swimming of trichodinids from one host to another. Trichodina cells swim with the aboral surface facing forwards. On surfaces, they move laterally, with the aboral surface facing the substrate.[1]

Pathogenesis

Most trichodinids are ectocommensal in that they use the fish only as a substrate for attachment, while they feed on suspended bacteria. Some species are certainly primary pathogens, however, since they occur in sterile sites (e.g. urinary system), or provoke pronounced responses on the part of the host (e.g. Tripartiella on gills).

When trichodinids become a problem in aquaculture, it usually indicates eutrophication or poor water quality. High bacterial loads provide abundant food for trichodininds, which subsequently proliferate on hosts and then cause attachment-related pathologies.

References

- Kreier, Julius P. (2013-10-22). Parasitic Protozoa. Academic Press. ISBN 9781483288796.

- Lom, Jiří; Dyková, Iva (1992). Protozoan Parasites of Fishes. Developments in aquaculture and fisheries science. Vol. 26. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-89434-2.