Trimerorhachis

Trimerorhachis is an extinct genus of dvinosaurian temnospondyl within the family Trimerorhachidae. It is known from the Early Permian of the southwestern United States, with most fossil specimens having been found in the Texas Red Beds. The type species of Trimerorhachis, T. insignis, was named by American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1878. Cope named a second species from Texas, T. mesops, in 1896. The species T. rogersi (named in 1955) and T. greggi (named in 2013) are also from Texas, and the species T. sandovalensis (named in 1980) is from New Mexico.

| Trimerorhachis Temporal range: Early Permian, | |

|---|---|

| |

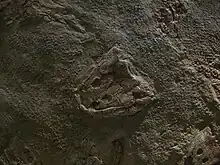

| A large skull of Trimerorhachis insignis (AMNH 7116) in the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Suborder: | †Dvinosauria |

| Family: | †Trimerorhachidae |

| Genus: | †Trimerorhachis Cope, 1878 |

| Species | |

| |

Description

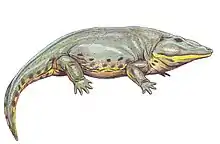

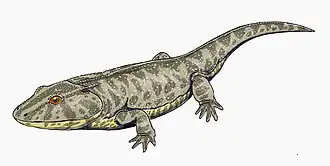

The length of the largest specimens of Trimerorhachis is estimated to have been almost a metre (3.3 feet) in length. Trimerorhachis has a large triangular head with upward-facing eyes positioned near the front of the skull. The trunk is long and the limbs are relatively short. The presence of a branchial apparatus indicates that Trimerorhachis had external gills in life, much like the modern axolotl.[1] The body of Trimerorhachis is also completely covered by small and very thin osteoderms, which overlap and can be up to 20 layers thick. These osteoderms act as an armor-like covering, especially around the tail. Their weight may have helped Trimerorhachis sink to the bottom of lakes and rivers where it would feed.[2]

History

Trimerorhachis was first described by Edward Drinker Cope in 1878. Specimens are often preserved as masses of bones that are mixed together and densely packed in slabs of rock.[3] Fossils are rarely found in articulation, although a slab of rock has been found with sixteen skulls and their associated vertebrae in an intact position.[1] Most of these fossils preserve skulls and dorsal vertebrae, but rarely any other bones. Paleontologist S.W. Williston of the University of Chicago commented in 1915 that "it will only be by the fortunate discovery of a connected skeleton that the tail, ribs, and feet will be made known."[3] A nearly complete specimen was discovered the following year near Seymour, Texas, and Williston was able to describe the entire postcranial skeleton of Trimerorhachis.[4]

In 1955, paleontologist Edwin Harris Colbert described the scales of Trimerorhachis. He noted that they were oval-shaped and overlapping and that each had a base layer of longitudinal striations covered by another layer ring-like ridges, the growth rings of the scales. The scales were more similar to fish scales than they were to reptile scales.[5] In 1979, paleontologist Everett C. Olson claimed that there were no such scales in Trimerorhachis, and that Colbert was incorrect in his interpretation of the body covering of Trimerorhachis.[2]

A second species called T. sandovalensis was named from New Mexico in 1980. A nearly complete skeleton from the Abo Formation near Jemez Springs has been designated the holotype, but other fossils of the species are found throughout the state, giving it a wide distribution.[6]

Paleobiology

Environment

Trimerorhachis was probably a fully aquatic temnospondyl. Like most dvinosaurs, it had external gills. The interclavicle and clavicle of the pectoral girdle are both very large, a feature that is shared with other aquatic temnospondyls. Many bones are poorly ossified, indicating that Trimerorhachis was poorly suited for movement on land.[7] Trimerorhachis was probably an aquatic predator that fed on fish and small vertebrates.[2] Microanatomical data also suggest a fairly aquatic lifestyle, as shown by the obvious osteosclerosis of its femur.[8]

During the Early Permian, the area of New Mexico and Texas was a broad coastal plain that stretched from an ocean in the south to highlands in the north. Other common animals that lived alongside Trimerorhachis included lungfish and crossopterygians, the lepospondyl Diplocaulus, and the large sail-backed synapsid Dimetrodon.[6]

Brooding

Small bones that likely belong to immature Trimerorhachis individuals have been found in the pharyngeal pouches of larger Trimerorhachis specimens. At first these bones were thought to be part of the branchial arches which surround the pouch, or remains of prey that had just been eaten before the animal died. If Trimerorhachis was a mouth brooder, the closest living analogue would be Darwin's Frog, which broods its young in its vocal sac. The bones in Trimerorhachis belong to juveniles that were much larger than those of Darwin's Frog, however. The young of the Gastric-brooding frogs of Australia were comparable in size to those of Trimerorhachis but were brooded in the stomach rather than the throat. The number of brooded young in Darwin's Frog and the Gastric-brooding frogs is also much higher than that of Trimerorhachis, as only a few individuals can be distinguished in the collection of bones. The only living amphibian that raises similarly sized young is the Golden coquí, although it does so through ovovivipary rather than brooding.[2]

Another possible explanation for the small bones is that they were originally located in the throat and were pushed into the pharyngeal pouch during fossilization. If this was the case, Trimerorhachis may have eaten its young instead of brooding them. This type of cannibalism is widespread in living amphibians, and most likely occurred among some prehistoric amphibians as well.[2]

See also

References

- Case, E.C. (1935). "Description of a collection of associated skeletons of Trimerorhachis". University of Michigan Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. 4 (13): 227–274. hdl:2027.42/48206.

- Olson, E.C. (1979). "Aspects of the biology of Trimerorhachis (Amphibia: Temnospondyli)". Journal of Paleontology. 53 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 1304028.

- Williston, S.W. (1915). "Trimerorhachis, a Permian temnospondyl amphibian". The Journal of Geology. 23 (3): 246–255. Bibcode:1915JG.....23..246W. doi:10.1086/622229. JSTOR 30066442.

- Williston, S.W. (1916). "The skeleton of Trimerorhachis". The Journal of Geology. 24 (3): 291–297. Bibcode:1916JG.....24..291W. doi:10.1086/622329. JSTOR 30079362. S2CID 128401645.

- Colbert, E.H. (1955). "Scales in the Permian amphibian Trimerorhachis" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (1740): 1–17.

- Berman, D.S.; Reisz, R.R. (1980). "A new species of Trimerorhachis (Amphibia, Temnospondyli) from the Lower Permian Abo Formation of New Mexico, with discussion of Permian faunal distributions in that state". Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 49: 455–485.

- Pawley, K. (2007). "The postcranial skeleton of Trimerorhachis insignis Cope, 1878 (Temnospondyli: Trimerorhachidae): a plesiomorphic temnospondyl from the Lower Permian of North America". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (5): 873–894. doi:10.1666/pleo05-131.1. S2CID 59045725.

- Quémeneur, S.; de Buffrénil, V.; Laurin, M. (2013). "Microanatomy of the amniote femur and inference of lifestyle in limbed vertebrates". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (3): 644–655. doi:10.1111/bij.12066.