Flat-spired three-toothed snail

The flat-spired three-toothed snail (Triodopsis platysayoides)—also known as the Cheat three-toothed snail after the Cheat River in West Virginia—is a species of air-breathing land snail, a terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Polygyridae.

| Flat-spired three-toothed snail | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Family: | Polygyridae |

| Genus: | Triodopsis |

| Species: | T. platysayoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Triodopsis platysayoides (Brooks, 1933)[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Polygyra platysayoides Brooks, 1933 | |

Description

The color of the body of the animal in this species is pale gray. The shells of adult snails are 18–22 mm in width and 8 mm in height.[2]

The shell of Triodopsis platysayoides is thin, right coiled (or dextral), and translucent, with 5 whorls. It is extremely flattened in shape.[2] The umbilicus is open and wide. The shell is pale brown (light horn) in color; the exterior surface of the peristome is yellowish and punctate.[2]

The aperture of the shell is oblong-lunate.[2] The lip is thickened and white.[2] There is a thick tongue-shaped tooth in the parietal wall of the aperture.[2]

Taxonomy

Triodopsis platysayoides is now a formally recognized species. It was first collected by Graham Netting at Coopers Rock, and later described by Stanley Brooks as Polygyra platysayoides from the area of Coopers Rock State Forest.[2] The type specimen is stored in the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History under number 62.23750.[2]

The taxonomic status of T. platysayoides was subsequently questioned. In 1940 the American biologist Henry Augustus Pilsbry considered it to be a distinct species, and he also transferred it to the genus Triodopsis.[3] However, based on rather limited information, Vagvolgyi classified Triodopsis platysayoides as merely a subspecies of Triodopsis complanata in 1968.[4] This reclassification was not widely accepted however, and in 1974 Solem concluded that the available evidence did support full species status for this snail.[5]

Triodopsis platysayoides was confirmed as a valid species with a unique penial morphology in 1988.[6] Species status was also confirmed in 1988 by starch-gel electrophoresis of foot tissue, while examining evolutionary relationships among 40 species of tridopsine snails in eastern North America. Populations were divided into family trees showing the phylogenetic relationships among 18 groups of species. Nine of these groups consisted of a single species, of which Triodopsis platysayoides was one group.[6]

Distribution

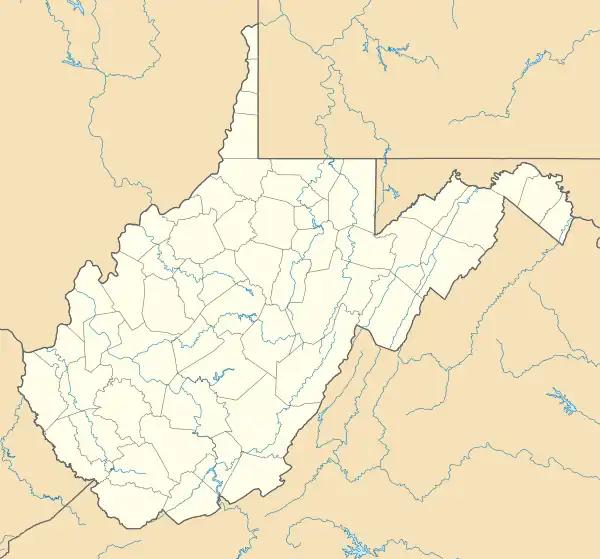

The red dot is Coopers Rock State Forest, where the snail Triodopsis platysayoides is found.

This species of snail is endemic to the United States.

The flat-spired three-toothed snail is found only in West Virginia, among Upper Connoquenessing sandstone outcroppings and boulders, in a restricted area along the rim of the Cheat River gorge. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service considers this snail to be threatened since 1978.[7]

Ecology

Little is known about the life of this animal, but the West Virginia captive breeding program and past survey efforts have provided some information.[8]

This snail is primarily active at night (nocturnal). Optimum snail activity occur during spring and early summer, especially during cool, moist weather conditions when air temperatures are between 60 and 65 degrees Fahrenheit with relative humidity greater than 85 percent.[9]

During the daytime, the species has primarily been found on the ceiling, wall, or floor of rock structures. During the night, the snails have been found equally on both rock surfaces, and on the leaf litter near rock features. The species has been observed foraging and resting under wet leaves (next to rock structure), and moving across the leaf litter to a rock feature.[9] There are no known diseases of Triodopsis platysayoides.[8]

Habitat

The snail lives in cracks and crevices in rocks, and in the surrounding leaf litter.

In dry seasons the snails retreat in among the huge, scattered and split boulders just below the summit.[7] Triodopsis platysayoides specimens are typically observed within 1 meter of a rock feature. They can be found in cool, moist, deep fissures in shale, sandstone and limestone outcrops, and in talus. The snail occurs in various outcrops of rock from the bottom of the gorge to the ridgetops.

Rock outcrops that are one meter or more in height appear to be potential habitat, as long as there are cracks and crevices that are at least one meter deep. The snail appears to prefer rock talus, but is also found in cliffline areas that contain deep, dark crevices. When the two habitats coincide (rock talus and cliffline), then Triodopsis platysayoides is more often found in the talus.[8]

While plant associations and the ages of tree occurring at known Triodopsis platysayoides sites vary greatly, several plant species are commonly found at these sites: sweet birch, rhododendron, and red maple.[10][11] Some sites are covered in old growth trees, while others are occupied by saplings. In some cases, open grape arbors grow over the talus.[9] The rock structure itself appears to be more important to the snail than the age of trees or the composition of the vegetation growing on or over the rocks.[9]

The slope aspect is also a factor. North and northeast slopes in the Cheat gorge provide naturally cooler and moister habitats than south and southwest facing slopes. Thus, heavy canopy cover may be more important on south and southwest facing slopes, in order to provide shade and humidity.[8]

Feeding habits

Triodopsis platysayoides feeds on a varied diet of over 20 or so documented foods, including several aged leaves and flower blossoms, fresh catkins, fresh and aged pack rat feces, lichens, mushrooms and crickets.[9][11]

Calcium may be a limiting factor for this snail, especially for those living among sandstone habitats which are predominantly acidic. Triodopsis platysayoides has been observed feeding on aged beech leaves and catkins, which are good sources of calcium, as well on the shells of Triodopsis denotata, Mesomphix cupreus, and its own kind.[9]

Life habits

Mature snails are hermaphroditic. A mating pair will cross-fertilize, and each individual may lay eggs. They bury the eggs in soil or leaf litter.[12] A captive colony of Triodopsis platysayoides laid small cluster of 3 to 5 eggs in the soil under the leaf litter in the spring and summer.[5]

Once hatched, young snails grow rapidly, and can reach maturity within their first summer.[12]

Triodopsis platysayoides is thought to be a relatively long-lived land snail. Based upon shell growth rings, these snails reach maturity at 3 years in the wild, or at 2 years in captivity.[13]

Approximately 33 to 67% of the individuals located in the field were adults.[11]

Populations trends

Before 1981, only one very restricted population of Triodopsis platysayoides was known. On one occasion, 50 individuals were observed and a population of "several hundred" was estimated (in 1972).[14] A later estimation in 1974 was that the population represented about 300 to 500 living individuals.[7][15] Field surveys at this same location found only 35 individuals however.

In 1984, 12 Triodopsis platysayoides were marked and released, but no recaptures were obtained.[5]

Increasing numbers of the snail were noticed at Coopers Rock State Forest after the site was fenced to control human access.[9][16] However such observation of snail numbers cannot be used to deduce trends, as other snails show short-term fluctuations of 10 to 15 times when there is such a low population total.[17]

Triodopsis platysayoides appears to be a relatively common snail species where it is found.[9] Although many other species of snails have been documented coexisting with Triodopsis platysayoides, they generally do not exceed Triodopsis platysayoides numbers.[9] In many cases, Triodopsis platysayoides was the most common snail, sometimes exceeding all other snail species combined.

Genetic samples to detect differences in populations were taken on both sides of the gorge. The analysis had not been finished in 2007[8] and at that point it was not known whether populations are isolated or connected genetically.

Vulnerability

Because of its limited range, this snail is especially vulnerable to natural or human-caused incidents that could destroy most, or even all, of its populations.

Hikers inadvertently disrupt the leaf litter cover, and crush snails. Rock climbers, too, have killed snails and destroyed their habitat unknowingly.[12]

Human activities such as logging, housing developments, and forest fires can all alter the environmental conditions that the flat-spired three-toothed snail needs to survive.[12]

Conservation

Recovery efforts for this animal have included fencing the occupied habitat, and land acquisition of approximately 1,100 acres (4,45 km²) of snail habitat.[12] (The fence is not to keep snails inside the area, but to keep people out of the habitat of the snails.)

Currently the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources is working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to develop a "Safe Harbor Agreement" for the snail on their properties. Additionally, they are working with private landowners to encourage protection of the snail by designing special timber management guidelines.[12]

The state of West Virginia, the Nature Conservancy, private landowners, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, are all sharing the effort to prevent the flat-spired three-toothed snail from sliding into extinction.[12]

References

This article incorporates public domain text (a public domain work of the United States Government) from references.[8][12]

- Mollusc Specialist Group (1996). "Triodopsis platysayoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T22194A9364206. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T22194A9364206.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- Brooks S. T. (October 22, 1932) 1933. Polygyra platysayoides nov. spec. Nautilus, volume 46, number 2: 54–55.

- Stihler C. W. 1994. New records for the land snail Tridopsis platysayoides. West Virginia Acad. Sci. 66(numbers 2–4): 2–6.

- Vagvolgyi J. 1968. Systematics and evolution of the genus Tridopsis (Mollusca: Pulmonata: Polygyridae). Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. 136: 145–254.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1985. Endangered species information system record. 13 pp.

- Emberton K. C. 1988. The genitalic, allozymic, and conchological evolution of the eastern North American tridipsinae (Gastropoda; Pulmonata: Polygyridae). Malacologia 28: 159–273.

- July 3, 1978. Determination that Seven Eastern U.S. Land Snails are Endangered or Threatened Species. Federal Register, Vol. 43, Number 128.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service September 2007 Flat-spired three-toothed Land Snail (Triodopsis platysayoides) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 25 pp.

- Dourson D. 2007. Survey protocol for Cheat Threetooth (Triodopsis platysayoides). Report submitted to West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, Elkins, West Virginia, 28 pp.

- Caldwell R. S., Copeland J. E. & Mears G. L. 2006. Findings for habitat analysis of Triodopsis platysayoides (Brooks 1933), Cheat threetooth. Cumberland Mountain research Center of Lincoln Memorial University, Kentucky, 35 pp. and attachments.

- Hotopp K. 2000. Cheat Threetooth (Triodopsis platysayoides Brooks) inventory 2000. Unpublished report to U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, Elkins, West Virginia, 38 pp.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. December 2005. Flat-spired three-toothed Snail Triodopsis platysayoides.

- Hotopp K. 2003. Land snails of selected Pennsylvania natural areas. Unpublished report to the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 44 pp.

- Grimm F. W. 1972. Office of Endangered Species Information Form.

- Solem A. 1974. Office of Endangered Species Information Form.

- Craig Stihler, personal communication 2007. In: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service September 2007 Flat-spired three-toothed Land Snail (Triodopsis platysayoides) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. 25 pp.

- Solem A. 1982. Letter to William Ashe. U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, Newton Corner, Massachusetts, 1 pp.

External links

- Triodopsis platysayoides species profile from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Triodopsis platysayoides information from The Official World Wildlife Fund Guide to Endangered Species