1997–98 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season

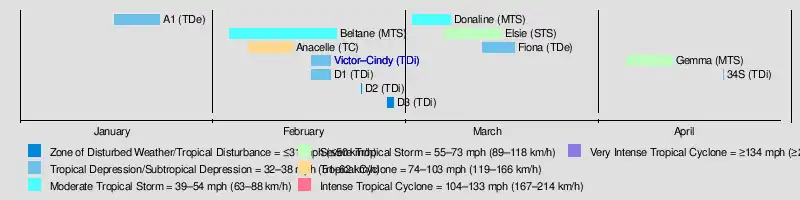

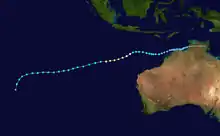

The 1997–98 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season was fairly quiet and had the latest start in 30 years. The first tropical disturbance originated on January 16, although the first named storm, Anacelle, was not upgraded until February 8, a record late start. The last storm to dissipate was an unusually late tropical depression in late July. Many of the storms suffered from the effects of wind shear, which contributed to there being only one tropical cyclone – equivalent to a minimal hurricane. The season also occurred during a powerful El Niño.

| 1997–98 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 16, 1998 |

| Last system dissipated | April 22, 1998 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Anacelle |

| • Maximum winds | 140 km/h (85 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 950 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total disturbances | 16 |

| Total depressions | 11 |

| Total storms | 5 official, 5 unofficial |

| Tropical cyclones | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 88–144 total |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

Tropical Depression A1, the first of the season, moved throughout most of Mozambique in January, causing landslides and flooding. One landslide affected Milange District, where many houses were swept into a river. Landslides killed between 87 and 143 people in the country. In February, Cyclone Anacelle buffeted several islands with gusty winds after becoming the strongest storm of the season, reaching maximum sustained winds of 140 km/h (85 mph). Although Anacelle was the first named storm of the season, another tropical depression preceded it that crossed Madagascar several times. The depression eventually became Tropical Storm Beltane, and lasted 17 days. Beltane caused flooding across Madagascar due to heavy rainfall, which killed one person and left locally heavy crop damage. There were several other disturbances in February, including Cindy which dissipated 50 days after it originated, as well as a disturbance that brought heavy rainfall to Réunion and Mauritius. The rest of the season was fairly quiet, mostly with short-lived tropical disturbances or storms.

Season summary

During the year, the Météo-France office on Réunion (MFR) issued warnings for tropical systems in the region as the Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre.[1] In the year, MFR tracked tropical cyclones south of the equator from the coast of Africa to 90° E.[2] The Joint Typhoon Warning Center also issued warnings in an unofficial capacity.[3]

The season had the latest start in 30 years, with the first depression forming in January.[1] The first storm, Anacelle, was not named until February 8, which retains the record for the latest date of the first named storm.[4] For the early portion of the season, there were unusually quiet conditions across much of the basin, along with higher than normal pressure. The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) associated with the monsoon only became active in February, allowing tropical cyclogenesis to occur more frequently. There were six tropical storms during the season, of which only one attained tropical cyclone status; these are below the averages of 9 and 4, respectively. No storms attained intense tropical cyclone status. The season's low activity contrasted that of the previous season, which was much more active. There were 18 days in which a storm was active, the lowest since 1982–83. An ongoing El Niño was evident during the season.[1]

Systems

Tropical Depression A1

| Tropical depression (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 16 – January 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 km/h (35 mph) (10-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

The first system of the season originated out of a circulation that persisted in the northern Mozambique Channel on January 15. Convection developed around the center near Grande Comore, meriting its classification Tropical Disturbance 1. Moving southwestward, the system organized into a tropical depression on January 17, developing a curved band of convection. Further intensification was halted as the system moved ashore Mozambique near Angoche. The depression turned to the south over land, remaining over inland Mozambique for several days.[1] On January 18, the JTWC classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 13S, estimating winds of 65 km/h (40 mph),[3] despite the storm being 55 km (35 mi) inland.[5] The agency quickly downgraded the storm to tropical depression status, but briefly re-upgraded it on January 19 as the system crossed over the extreme western Mozambique Channel. The agency again downgraded it after the storm moved ashore. By contrast, the MFR assessed that the system remained a tropical depression and placed the circulation farther inland.[6] On January 20, the depression turned to the southeast over open waters, influenced by a trough to the south. Despite warmer waters, the system was unable to re-intensify much due to the presence of wind shear,[1] although the JTWC again upgraded the system to tropical storm status for a third and final time.[6] The depression approached tropical storm intensify after developing increased convection over the center, but it weakened again on January 22. On the next day, the system dissipated just off the southern coast of Madagascar.[1]

In its formative stages, the depression dropped beneficial rainfall in the Comoros, reaching 163 mm (6.4 in) at Prince Said Ibrahim International Airport. While the depression was over land, the plume of warm air from the open waters sustained heavy convection over the circulation, which dropped heavy rainfall across eastern Mozambique.[1] The rains caused landslides and flooding in the country, which disrupted transport in three provinces, damaging several bridges.[7][8] The most significant landslide occurred in Milange District at nighttime, which swept houses into a river; about 2,500 people were left homeless in the village. There were 73 confirmed fatalities, with another 70 people missing and presumed killed.[9] However; the International Disaster Database (EM-DAT) later placed the total number of casualties at 87.[10] Rainfall also extended into Malawi, where villages were flooded and crops were damaged.[5] While the system was accelerating to the southeast away from Mozambique, it produced gale-force winds on Europa Island.[1]

Moderate Tropical Storm Beltane

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 3 – February 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 992 hPa (mbar) |

A northerly flow produced a low-pressure area on February 1 in the central Mozambique Channel. Influenced by the monsoon trough, the system developed a distinct circulation on February 3 near Juan de Nova Island, becoming a tropical disturbance and bringing gusts of 50 km/h (30 mph) to the island. The convection organized around the circulation while moving eastward. Conditions were favorable for further strengthening, although the system made landfall in western Madagascar between Maintirano and Morondava on February 5. After progressing slightly inland, the disturbance looped and turned to the south. The circulation became difficult to locate, but surface observations helped track the circulation southward through the country. Late on February 8, the system reached the open waters south of Madagascar and quickly redeveloped convection southeast of the center, displaced by wind shear, and it was reclassified as a subtropical depression.[1] The JTWC briefly classified it as Tropical Cyclone 21S on February 9 with winds of 65 km/h (40 mph).[3]

A building ridge to the south turned the system northeastward on February 10 and later to the northwest, bringing it back over southwestern Madagascar. On February 11, the circulation again reentered the Mozambique Channel, and subsequently the thunderstorms rebuilt over the poorly defined center. A trough behind the ridge allowed the system to turn to the southwest and later southeast. An increase in convection on February 15 organized into a curved band, and MFR upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Beltane on the next day off the west coast of Madagascar.[1] The JTWC also classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 23S on February 16,[3] possibly due to the extended duration between issuing advisories.[11] Strong wind shear stripped the convection from the center as Beltane approached southwestern Madagascar on February 17. Another building ridge turned the weakened depression to the northwest across the Mozambique Channel, finally dissipating on February 20 near the mouth of the Zambezi. The remnants later moved across Mozambique accompanied by locally heavy rainfall.[1]

Due to its trajectories across Madagascar, Beltane brought heavy rainfall to the country.[1] The persistent precipitation damaged crops, up to 100% in some areas, and forced thousands to evacuate their houses. Floodwaters covered the village of Vohipeno, killing one person.[12] Several roads and bridges were also washed away.[13]

Tropical Cyclone Anacelle

| Tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 6 – February 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (10-min); 950 hPa (mbar) |

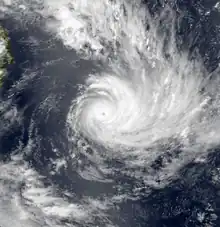

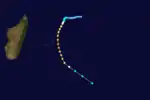

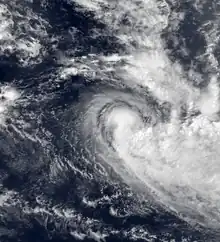

On February 5, the ITCZ spawned an area of convection about 1,000 km (620 mi) southwest of Diego Garcia. The system slowly organized, aided by warm waters and weakening wind shear. On February 6, it developed into a tropical disturbance, and became Tropical Storm Anacelle two days later.[1] Also on February 8, the JTWC initiated advisories on the storm as Tropical Cyclone 20S.[3] The storm initially moved westward due to a ridge to the north, although the motion shifted to the southwest on February 9 due to a trough and the influence of the system that would become Tropical Storm Beltane. Anacelle developed an eye feature on February 10, indicating that it attained tropical cyclone status, or winds of at least 120 km/h (75 mph). Around that time, Anacelle passed just west of St. Brandon.[1] On February 11, the cyclone passed about 100 km (60 mi) east of Mauritius. Shortly thereafter, Anacelle attained peak winds while presenting a 30 km (19 mi) eye.[1] It reached peak winds of 140 km/h (85 mph), according to MFR, while the JTWC estimated peak winds of 215 km/h (135 mph).[14] An approaching trough weakened the cyclone and steered it southeastward, causing the eye to disappear. On February 13, Anacelle became extratropical, although the remnants continued southeastward, passing near Île Amsterdam on the next day and re-intensifying on February 15 in the southern Indian Ocean.[1]

While passing near St. Brandon, Anacelle produced peak winds of 101 km/h (63 mph), with gusts to 151 km/h (94 mph). Later, the storm produced gusty winds of less than 120 km/h (75 mph) on Mauritius,[1] along with 125 mm (4.9 in) of rainfall at Port Louis.[11] The extratropical remnants also brought gale-force winds to Île Amsterdam.[1]

Moderate Tropical Storm Donaline

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 4 – March 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (10-min); 988 hPa (mbar) |

A large area of low pressure between the Chagos Archipelago and the Mascarene Islands spawned a small tropical disturbance on March 4. Moving southeastward, the system slowly developed as wind shear in the region slowly decreased. Despite only being a tropical depression, it was named Donaline on March 5.[1] On the next day, the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 26S.[3] Increased convection organized into a central dense overcast, and Donaline intensified into a minimal tropical storm,[1] reaching peak winds of 75 km/h (45 mph) according to the MFR. In contrast, the JTWC estimated peak winds of 100 km/h (60 mph).[15] The wind shear returned, causing weakening and dislocating the circulation from the convection. On March 10, Donaline became extratropical and was absorbed by a cold front two days later.[1]

Severe Tropical Storm Elsie

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 2 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 9 (entered basin) – March 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (10-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

On March 7, a low-pressure area persisted west of the Cocos Islands in the Australian basin. It drifted westward, entering the south-west Indian Ocean on March 9 as a tropical disturbance. It remained weak, with little convection over the center. Outflow gradually increased, although satellite imagery was limited in the region to only one image per day. Late on March 12, the satellite imagery indicated a well-defined tropical storm with curved convection, and the MFR immediately upgraded it to Severe Tropical Storm Elsie,[1] estimating peak winds of 100 km/h (60 mph). By contrast, the JTWC estimated winds of 165 km/h (105 mph),[16] having classified it as Tropical Cyclone 27S that day.[3] By that time, the storm was moving steadily to the southwest due to a trough in the region related to the remnants of Donaline. Increased wind shear caused steady weakening, removing the circulation from the convection on February 14. On the next day, Elsie weakened to tropical depression status as it curved southward. A building ridge to the south turned the system to the east, gradually looping back to the northwest. Elsie eventually dissipated on March 20.[1]

Tropical Depression Fiona

| Tropical depression (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | March 15 – March 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 55 km/h (35 mph) (10-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

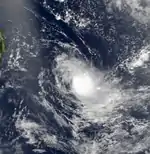

While Elsie was weakening and turning to the south, another system was forming near St. Brandon. Convection associated with the monsoon trough persisted on March 13, becoming a tropical disturbance two days later. The ridge steered the system to the southwest toward Rodigues, and conditions were expected to allow for intensification. As a result, the Mauritius Meteorological Service named the disturbance as Fiona on March 16. On the next day, Fiona intensified into a tropical depression,[1] reaching peak winds of only 55 km/h (35 mph).[17] Also on March 17, the JTWC initiated advisories on Tropical Cyclone 28S.[3] Around this time, Fiona passed about 200 km (120 mi) southeast of St. Brandon. After peaking, the convection decreased due to wind shear, causing the winds to fluctuate. On March 20, the circulation became exposed from the thunderstorms and approached 80 km (45 mi) east of Mauritius,[1] producing wind gusts of 70 km/h (45 mph).[11] The next day, Fiona dissipated into an approaching cold front.[1]

Moderate Tropical Storm Gemma

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 7 – April 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (10-min); 985 hPa (mbar) |

After an extended period of inactivity, the ITCZ produced two areas of convection – one was located about 550 km (340 mi) south-southwest of Diego Garcia, and the other was located 900 km (560 mi) east-southeast of that system. Both were classified as tropical disturbances on April 7 and subsequently interacted with each other.[1] The eastern system, classified as Tropical Cyclone 33S,[3] quickly dissipated due to strong wind shear and was absorbed into the western system. The disturbance continued to organize and developed a central dense overcast over the center, becoming Tropical Storm Gemma on April 8. A ridge and a trough steered the storm to the southeast and later to the east.[1] On April 9, Gemma attained peak winds of 85 km/h (55 mph), according to the MFR, while the JTWC estimated 130 km/h (80 mph) winds.[18] As with most other storms in the year, increased wind shear caused the storm to weaken. The weaker system isolated it from the upper-level steering, causing the circulation to loop southwestward. On April 16, Gemma dissipated far to the east of Rodrigues.[1]

Other systems

In addition to the named systems, there were nine tropical depressions or disturbances tracked by the MFR,[1] and several by other agencies.

On January 2, the tropical depression that was once Cyclone Selwyn crossed 90° E from the Australian region, but dissipated the next day.[19]

On February 8, a tropical low formed just north of Western Australia from the remnants of Cyclone Katrina, which earlier formed off the east coast of Australia. The low moved generally westward due to a strong ridge to the south. Given the name Victor, the storm intensified to a peak of 120 km/h (75 mph), before weakening steadily, due to increased wind shear. On February 14, the storm weakened to tropical depression status.[20] Victor crossed into the south-west Indian Ocean on February 16 with a well-defined circulation but little convection. Despite being downgraded to a tropical disturbance, the system was named Cindy by the Mauritius Meteorological Service on February 16. The system continued gradually weakening while turning more to the southwest, dissipating on February 19.[1] This marked a 50‑day period in which the same system was active.[20]

After Cyclone Anacelle became extratropical, an area of convection developed about 700 km (430 mi) northeast of Rodrigues on February 14. The circulation moved southwestward, organizing into Tropical Disturbance D1 on February 16. Later that day, it was upgraded to tropical depression status after the convection organized into a central dense overcast,[1] and on the same day the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 24S.[3] Increased wind shear weakened the depression as a trough turned it more to the southeast. On February 19, the trough absorbed the system.[1]

After the disturbance dissipated, a large low-pressure area persisted east of Madagascar with several associated circulations. On February 24, Tropical Disturbance D2 passed about 160 km (100 mi) west of Réunion, and continued to the southeast, passing south of Mauritius. Wind shear stripped the convection from the center and caused it to dissipate. Over a nine-day period, the system dropped nearly 2 m (6.6 ft) of rainfall in portions of Réunion, including nearly 700 mm (28 in) at Salazie on February 24; at that station, 255 mm (10.0 in) of precipitation fell in just three hours. Gusts reached 100 km/h (62 mph) in some locations.[1] The storm caused flooding and landslides on the island as well as power outages. Rainfall also reached 240 mm (9.4 in) on Mauritius. Residents were generally caught off guard by the storm due to the lack of warnings.[11] Tropical Disturbance D3 also developed before March.[1]

Although Tropical Storm Gemma was the final named storm, there were four subsequent tropical disturbances. The first formed toward the end of April after Gemma dissipated in the same general region.[1] Named Tropical Cyclone 34S by the JTWC, it moved westward throughout its duration but failed to intensify due to wind shear. On April 22, the system dissipated,[21] never having developed beyond tropical disturbance status. The last disturbance of the year formed on July 20 about 1480 km (920 mi) east of Diego Garcia. The system moved generally southwestward, dissipating on July 23 due to wind shear. At the time, the tropical cyclone year for the basin lasted from August 1 to July 31 of the following year, although the JTWC considers the start of the tropical cyclone year to begin on July 1. As a result, the MFR considered the system Tropical Disturbance H4 while the JTWC classified it as Tropical Cyclone 01S.[22]

Storm names

A tropical disturbance is named when it reaches moderate tropical storm strength. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status west of 55°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Madagascar assigns the appropriate name to the storm. If a tropical disturbance reaches moderate tropical storm status between 55°E and 90°E, then the Sub-regional Tropical Cyclone Advisory Centre in Mauritius assigns the appropriate name to the storm. A new annual list is used every year so no names are retired.[23]

|

|

|

See also

References

- Philippe Caroff (1997). 1997-1998 Cyclone Season in the South-West Indian Ocean (PDF) (Report). Météo-France. Retrieved 2014-05-03.

- Philippe Caroff; et al. (June 2011). Operational procedures of TC satellite analysis at RSMC La Réunion (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1999). "South Pacific And South Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (Report). United States Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Philippe Caroff. "Subject B3) When was the earliest tropical cyclone named ? The latest ?". Frequently Asked Questions (Report). Météo-France. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary January 1998". Gary Padgett. 1998. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 A19798:HSK1398 (1998016S12043). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Mozambique Landslides Report No. 1. United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). ReliefWeb. 1998-01-26. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Heavy Rains Cut Niassa's Roads In Mozambique. Pan African News Agency (Report). ReliefWeb. 1998-01-18. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- "Landslide death toll might hit 143". ReliefWeb. Reuters. 1998-01-29. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database". Université catholique de Louvain.

- "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary March 1998". Gary Padgett. 1998. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Madagascar: Post-Flood Food Security and Cholera Prevention (PDF) (Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. 1998-04-03. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- Madagascar: Post-Flood Food Security and Cholera Prevention (PDF) (Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. 1999-03-15. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 Anacelle (1998036S13066). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 Donaline (1998064S13061). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 Elsie (1998064S09093). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 Fiona (1998073S11065). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1998 Gemma (1998096S13071). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- Tropical Cyclone Selwyn (PDF) (Report). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- Tropical Cyclone Victor (PDF) (Report). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary April 1998". Gary Padgett. 1998. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary July 1998". Gary Padgett. 1998. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- Guy Le Goff (1997). 1996-1997 Cyclone Season in the South-West Indian Ocean (Report). Météo-France. p. 78. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

External links

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) Archived 2010-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Météo France (RSMC La Réunion)

- World Meteorological Organization

- RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee Final Report

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center 1998 ATCR

- 1997-98 Best Track Data from Météo France

- September 1997 to June 1998 Tropical Cyclone Summaries and Operational Track Data