Tropical Storm Cindy (1963)

Tropical Storm Cindy was a strong tropical storm which impacted portions of the United States Gulf Coast in September 1963. The third named storm of the 1963 Atlantic hurricane season, Cindy developed within a trough as a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico on 16 September. The disturbance quickly intensified, with a distinct eye becoming visible on satellite imagery as it drifted north-northwestwards toward the Texas coastline. After peaking with 1-minute maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h), it made landfall at High Island on the morning of 17 September at peak strength with an atmospheric pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg). Cindy remained nearly stationary for almost a day, dropping copious rainfall over the Texas coastal plain, before finally turning west-southwestward and dissipating west of Corpus Christi on 20 September.

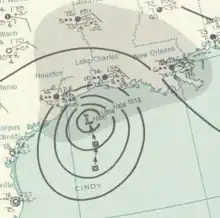

Weather map of Cindy on 17 September 1963 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 16 September 1963 |

| Dissipated | 20 September 1963 |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 996 mbar (hPa); 29.41 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 direct |

| Damage | $12.5 million (1963 USD) |

| Areas affected | Texas, Western Louisiana |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1963 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane watches and warnings were issued prior to Cindy's landfall, hastening evacuations in coastal areas of Louisiana and Texas, with many refugees seeking safety in local shelters. Although tide and wind damage was minimal, extreme rainfall totaling upwards of 23.50 in (597 mm) resulted in severe flooding in many areas of the Texas coastal plain; 4,000 homes were inundated in Jefferson, Orange, and Newton counties, many of them after a levee ruptured in Port Acres. Dozens of residents were forced to flee in rising flood waters, and many streets and roadways became impassable as a result of Cindy's flooding. Strong winds shattered glass windows, and schools throughout southeastern Texas were closed due to the hurricane. Widespread crop damage was observed, with rice, cotton, and pecan harvests suffering the worst. Overall, damage amounted to $12.5 million (1963 USD), and three deaths were recorded.[nb 1]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Cindy can be traced to a low-pressure area which formed within a trough positioned approximately 200 mi (320 km) east-northeast of Brownsville, Texas on 16 September, though inclement weather had been reported in the Gulf of Mexico the previous two days. The disturbance soon strengthened into a tropical storm, developing a well-defined circulation near 1800 UTC.[1] By the afternoon, it had become well-organized enough to prompt the New Orleans Weather Bureau office to initiate advisories on the storm, christening it Cindy.[2] A distinct eye was noted on radar around 2000 UTC, and around then a maritime report issued by the SS Sabine documented winds of hurricane intensity, which was the forecasters' basis for operationally upgrading the storm to a hurricane. While operationally classified as a Category 1 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), a reanalysis of the storm in November 2019 as part of the ongoing Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project determined that Cindy never reached hurricane intensity, instead peaking as a tropical storm with maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h).[3]

Despite its favorable environment, Cindy remained disorganized, featuring an asymmetric 20 mi (32 km)-wide eye; little further strengthening occurred over the course of the night.[2] Upon Cindy's landfall at High Island the following morning, its atmospheric pressure was measured at 996 mbar (hPa; 29.41 inHg),[1] and winds reached 75 mph (120 km/h).[4] Soon after moving ashore, Cindy became nearly stationary for 18 hours,[1] maintaining tropical storm status before weakening to a tropical depression at 1200 UTC on 18 September.[4] The remnants of Cindy gradually turned westward-to-southwestward and decreased in strength during 18 and 19 September. As a result of its abnormally slow movement and deterioration, extremely heavy rains were recorded over Texas and Louisiana, especially in the storm's northeastern quadrant.[1] Cindy finally dissipated on 20 September while situated west of Corpus Christi.[4]

Preparations and impact

In advance of Cindy's arrival, a hurricane watch was issued between Freeport, Texas and Grand Isle, Louisiana on 16 September. The New Orleans Weather Bureau office imposed a hurricane warning between Galveston, Texas and Vermilion Bay, Louisiana three hours later, and additionally replaced the earlier hurricane watch with a gale warning. After making landfall on the morning of 17 September, the hurricane warning for Cindy was discontinued, though flood warnings and small craft warnings remained in effect for coastal areas of southeastern Texas.[2] Mandatory evacuations were ordered for low-lying areas along a 300 mi (480 km) arc, and five buses were sent to help in evacuation efforts in Sabine County, Texas. Meanwhile, the Texas civil defense and disaster relief agency and other related organizations prepared for the storm as governor of Texas John Connally declared a state of emergency.[5] In Cameron Parish, Louisiana, approximately 5,000 individuals left the area prior to the storm,[6] while 6,000 fled in the state as a whole; in neighboring Texas, 3,600 individuals living along the state's shoreline heeded the Weather Bureau's warnings, evacuating to higher ground.[2] Emergency shelters opened along the Gulf Coast, with 1,500 taking refuge in Port Arthur, Texas, 525 in Beaumont, 1,078 in Galveston,[7] 300 in Port Bolivar, and 475 total in Texas City, Hitchcock, and Lamarque.[8] A state of emergency was declared in the city of Lake Charles, Louisiana, where officials prepared to feed up to 10,000 refugees as the Salvation Army and other relief agencies' volunteers were deployed to the region.[7]

One shrimp boat was initially reported missing and the tug Myra White transmitted a distress signal as its engines failed near an oil rig off of Galveston. High winds shattered glass windows at Port Arthur, Texas City, and Galveston, while schools were shut down in Galveston, Lamarque, Texas City, Alvin, and most of Galveston and Jefferson counties. Despite a brief power outage at Lamarque, electricity was quickly restored after the storm.[8] Powerful gusts downed branches, electrical poles, and tore off shingles in Port Arthur and Galveston, but damage was minimal at High Island, where Cindy made landfall.[6] The U.S. Coast Guard responded to four requests for assistance at Galveston, and nine vessels attempted to seek refuge at Port Arthur; the Coast Guard eventually permitted six to enter, and the other three apparently traveled to Galveston.[9] Meanwhile, to the northwest, the port of Houston was closed for the duration of the storm.[10] Trucks and boats were dispatched by civil defense officials in Jefferson County after declaring a state of emergency following numerous requests for assistance by residents of flooded homes. Two children, initially unaccounted for, were later found safe under a bridge abutment.[11]

In Amelia, a suburb of Beaumont, officials helped residents in low-lying neighborhoods to higher ground, and in Beaumont proper, flooding inundated streets, rendering some impassible.[12] The hurricane partially defoliated palm trees, leaving palm fronds on streets and roadways, and several structures were toppled or damaged along the coast. Overall damage, however, was minimal.[13] An 8 ft (2.4 m) levee sheltering Port Acres ruptured, forcing residents to stack 11,000 sandbags and dump sand to protect the suburb. There, storm waters inundated homes up to roof level, and after carp were swept into local farm fields, many locals fished for them with clubs; nearby, industrial complexes in Jefferson and Orange counties endured severe damage as well. Boats were tossed into the streets of Beaumont, and numerous highways were unusable for travel due to high water;[14] the widespread flooding forced police to rescue 30 residents in the Beaumont area.[15] The storm inundated rice, cotton, and pecan crops, with rice harvests suffering the worst impacts.[6] Two men left stranded on a burning fishing boat 50 mi (80 km) off of Morgan City, Louisiana were later rescued by the U.S. Coast Guard without issue.[9]

Tides and winds resulted in few problems, with flooding causing the majority of Cindy's damage; storm surge reached 3 to 5 ft (0.91 to 1.52 m) above normal levels, enough to destroy only a few piers and damage several boats. The hurricane's abnormally slow trajectory over the Texas coastal plain led to extremely high rainfall totals being measured in parts of Jefferson, Orange, and Newton counties in Texas, where storm waters inundated 4,000 homes, and Calcasieu and Vermilion parishes in Louisiana. The most extreme rainfall totals were measured in Deweyville, Texas, where 23.50 in (597 mm) of precipitation fell over a three-day period, with 20.60 in (523 mm) alone falling in 24 hours.[1] Farther north, Cindy inundated 25 businesses and 35 homes in Guthrie, Oklahoma, where up to 2.5 ft (0.76 m) of water forced 300 residents to flee.[16] Upwards of $11.7 million (1963 USD) in property damage was noted, and crop damage reached $500,000 in Texas and $360,000 in Louisiana; one man drowned after falling overboard on a boat taking oil rig personnel back to land, while two others drowned under high waters at Port Acres. Overall, Cindy inflicted $12.5 million in damage and three deaths.[1]

Notes

- All damage figures are in 1963 United States dollars (USD) unless otherwise noted.

References

- Gordon Dunn (March 1964). "The Hurricane Season of 1963" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 92 (3): 131–32. Bibcode:1964MWRv...92..128D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-92.3.128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- Hurricane Cindy, September 16–18, 1963 (PDF) (Report). Weather Bureau. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Sandy Delgado; Chris Landsea (November 26, 2019). 1961-1965 Atlantic Hurricane Database Reanalysis (PDF) (Report). NOAA. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (1 April 2014). Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2) (TXT) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- "Big Area Cleared Of People". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. 17 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Kyle Thompson (16 September 1963). "Hurricane Cindy Slams Texas, Then Collapses". Deseret News. United Press International. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Hurricane Cindy Slams Over Land". Florence Times. Associated Press. 17 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Kyle Thompson (17 September 1963). "Hurricane Dies As It Hits Texas Coast". Hendersonville Times-News. United Press International. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Hurricane Hits Texas; 13,000 Flee Coast Area". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. 17 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Cindy Lashes Coast". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. 17 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Texas Gets Heavy Rain". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 18 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Fading Cindy Dumps Deluge On Gulf Coast". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. 18 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Quick-Rising Hurricane Fizzles". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. 18 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "High Waters Follow Cindy; Many Routed". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. 19 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Cindy's Rain Wash Out Low Coastal Areas". The Dispatch. United Press International. 18 September 1963. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Stanley Holbrook (26 September 1963). Tropical Cyclone Reports, SC/Oklahoma, WBO. Weather Bureau (Report). United States Department of Commerce.