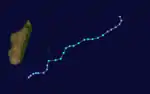

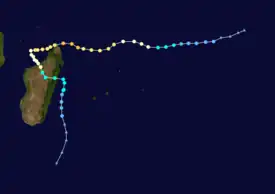

1983–84 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season

The 1983–84 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season featured above normal activity and several deadly storms. There was steady storm activity from December through April due to favorable conditions, such as warm sea surface temperatures and an active monsoon. The first named storm – Andry – was tied for the strongest with Bakoly, Jaminy, and Kamisy. Cyclone Andry passed near Agaléga island within Mauritius, damaging or destroying every building there and killing one person. It later struck Madagascar, the first of three storms to strike the nation within two months, which collectively caused $25 million in damage[nb 1] and 42 deaths. The third of these storms, Tropical Storm Domoina, caused deadly flooding in southeastern Africa that killed 242 people and caused $199 million in damage. The storm destroyed more than 50 small dams in Madagascar and caused the worst flooding in Swaziland in 20 years. In addition three of the first storms affecting Madagascar, Cyclone Bakoly in December left $21 million in damage on Mauritius.

| 1983–84 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | December 5, 1983 |

| Last system dissipated | April 16, 1984 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Andry, Bakoly, Jaminy, Kamisy |

| • Maximum winds | 195 km/h (120 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 927 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Tropical cyclones | 4 |

| Intense tropical cyclones | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 356 total |

| Total damage | $496 million (1984 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Less than two weeks after Domoina caused severe flooding in South Africa, Tropical Storm Imboa produced additional rainfall and high seas in the country, killing four people. The final storm of the season was Cyclone Kamisy, which caused $250 million in damage and 69 deaths when it made landfalls in northern and northwestern Madagascar. The cities near landfall were largely destroyed, and about 100,000 people were left homeless. The penultimate storm, Jaminy, was tied for the strongest storm in the basin after it crossed from the Australian region, where it was named Annette. Cyclone Fanja in January also crossed from the Australian region, where it was named Vivienne.

Season summary

During the season, the Réunion Meteorological Service tracked storms in the basin, using the Dvorak technique to estimate tropical cyclone intensities via satellite imagery.[1] The agency later became Météo-France's meteorological office at Réunion (MFR). At the time, the basin extended from the east coast of Africa to 80° E.[2] Eleven storms were named by the Mauritius Meteorological Service and the Madagascar Meteorological Service.[1] The rest of the naming list was Lalao, Monja, Nora, Olidera, Pelazy, Rija, Saholy, Tsira, Vaosolo, Wilfredy, Yannika, and Zozo.[3] The 11 named storms were slightly above the normal of 9, most of which formed in January and February. There were four intense tropical cyclones, which is twice the average. The increased activity of the season was in part due to enhanced easterlies, a strong monsoon trough, and warm water temperatures around 28 °C (82 °F) which extended to 25° S.[4]

In addition to the 11 named storms, there were two additional storms in the season, classified by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).[nb 2] The first developed in July in the Australian basin, and briefly crossed into the south-west Indian Ocean on July 14. Soon after it re-entered the Australian basin and dissipated.[6] The other formed just southeast of Diego Garcia on November 20. It tracked to the southwest, and the JTWC estimated peak 1 minute sustained winds of 85 km/h (55 mph). The storm dissipated on November 25 northeast of Mauritius.[7] In addition, Cyclone Daryl, which formed in the Australian basin on March 6, crossed into the south-west Indian Ocean on March 16 as a weakening storm without being renamed. Two days later it re-entered the Australian basin before dissipating.[8]

In December and January, three storms – Andry, Caboto, and Domoina – struck Madagascar in short succession. Collectively they dropped heavy rainfall, and some areas of the country reported precipitation totals that were 220% above normal. The storms damaged roads, bridges, dams, and croplands, wrecking 10,000 tons of rice. Damage from the three storms was estimated at $25 million, and 13,560 people were left homeless. The storms cumulatively killed 42 people.[9] After seven cyclones struck or affected the country, causing 23.9 billion Malagasy francs ($200 million 1984 USD)[nb 3] in crop damage, the African Development Bank approved a loan of 559 million Malagasy francs ($1.35 million 1989 USD)[nb 4] to rebuild the damaged water infrastructure. The program lasted until December 22, 1993, and consisted of repairing irrigation systems and dams.[12]

Systems

Intense Tropical Cyclone Andry

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 5 – December 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 927 hPa (mbar) |

On December 5, an area of convection persisted between Agaléga and Diego Garcia, which corresponded to a satellite-derived Dvorak rating of T2.0;[1] on this basis, MFR assessed the system as a tropical disturbance, and later that day, JTWC also initiated advisories.[13] The Réunion Meteorological Service named the system Andry. On December 7, the storm intensified into a tropical cyclone,[1] the same day that the JTWC upgraded Andry to the equivalent of a minimal hurricane.[13] After having moved to the west, the cyclone turned more to the west-southwest, and while doing so it passed just south of the Agaléga islands, producing wind gusts of 174 km/h (108 mph).[1] The storm damaged or destroyed every house on the island, leaving the 350 residents without power, food, water, or shelter. Andry also downed most of the coconut trees on the island, which was the source of employment for most residents. High waves flooded wells and contaminated the water supply.[9] The cyclone injured 30 people,[1] and killed one. The Mauritius government later evacuated residents to structures that were not destroyed. Following the storm, various countries donated to the country to assist, including France who sent crews from Réunion to set up shelter and provide care for the residents.[9] The island was largely rebuilt after about two years.[14]

Cyclone Andry reached peak winds of December 9, when MFR estimated winds of 170 km/h (105 mph). The next day, JTWC estimated 1 minute winds of 240 km/h (150 mph).[13] Around that time, Andry was passing just north of the northernmost tip of Madagascar at Diego-Suarez, where the storm produced wind gusts of 250 km/h (155 mph).[1] The cyclone weakened while curving to the southwest and later to the south,[13] making landfall on western Madagascar near Majunga with wind gusts of 198 km/h (123 mph). While over land and turning to the southeast, Andry rapidly weakened into a tropical depression, which later passed near the capital Antananarivo. The storm emerged back into the Indian Ocean on December 14, by which time the system was disorganized.[1] That day, MFR estimated that Andry dissipated, although the JTWC assessed that the system re-intensified slightly and turned sharply southwestward before dissipating over Madagascar on December 16.[13]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Bakoly

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 2 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 19 – December 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 927 hPa (mbar) |

On December 19, a tropical disturbance formed near Diego Garcia, which initially tracked to the south-southeast before turning to the southwest. Later that day, the system intensified to moderate tropical storm status, prompting the Mauritius Meteorological Service to name it Bakoly. The storm gradually intensified into an intense tropical cyclone, reaching peak winds of 170 km/h (105 mph) on December 23. After maintaining that intensity for about 12 hours, Bakoly weakened below cyclone status as it turned to the south-southeast. On December 25, the storm passed between Réunion and Mauritius, and later resumed its south-southwest trajectory. After executing a small loop, Bakoly turned to the southeast and dissipated on December 30.[1][15]

On Mauritius, Bakoly produced 197 km/h (122 mph) wind gusts and heavy rainfall, reaching 507 mm (20.0 in) at Midlands. The high winds caused roof damage, and eight people were injured on the island.[1] Bakoly caused power outages and damaged 4% of the telephone network. Damage was estimated at RS300 million (US$21 million).[nb 5][17] Passing within 100 km (60 mi) of Réunion, Bakoly produced 100 km/h (60 mph) winds and dropped 300 mm (12 in) of rainfall.[1]

Moderate Tropical Storm Caboto

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| |

| Duration | January 4 – January 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

MFR began tracking a tropical disturbance in the Mozambique channel on January 4. The next day, the agency estimated the system intensified into a moderate tropical storm,[18] prompting the Madagascar Meteorological Service to name it Caboto.[1] The storm moved southward along Madagascar's western coast, reaching peak winds of about 65 km/h (40 mph).[18] Caboto made landfall on January 7 to the north of the mouth of the Mangoky River, and crossed the southern portion of the country, emerging near Farafangana into the Indian Ocean. Winds associated with the storm reached 43 km/h (27 mph) at Morondava on the west coast and 63 km/h (39 mph) at Farafangana on the east coast. A developing ridge caused Caboto to slow after it reached open waters, executing a partial loop southwest of Réunion before turning to the south and dissipating on January 10.[1]

Severe Tropical Storm Domoina

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 19 – January 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

Domoina developed on January 16 off the northeast coast of Madagascar. With a ridge to the north,[1] the storm tracked generally westward and later southwestward. On January 21, Domoina struck eastern Madagascar. After crossing the country, Domoina strengthened in the Mozambique channel to peak winds of 95 km/h (60 mph). On January 28, the storm made landfall in southern Mozambique, and slowly weakened over land. Domoina crossed into Swaziland and later eastern South Africa before dissipating on February 2.[19]

In Mozambique, Domoina dropped heavy rainfall in the capital Maputo that accounted for 40% of the annual total.[9] Floods in the country destroyed over 50 small dams and left widespread crop damage just before the summer harvest.[9][20]

Later, the rains caused the worst flooding in over 20 years in Swaziland,[21] which damaged or destroyed more than 100 bridges.[22] Disrupted transport left areas isolated for several days.[23] In South Africa, rainfall peaked at 950 mm (37 in),[24] which flooded 29 river basins, notably the Pongola River which altered its course after the storm.[25] Flooding caused the Pongolapoort Dam to reach 87% of its capacity; when waters were released to maintain the structural integrity, additional flooding occurred in Mozambique, forcing thousands to evacuate.[26] Throughout the region, Domoina caused widespread flooding that damaged houses, roads, and crops, leaving about $199 million in damage. There were 242 deaths in southeastern Africa.[9][20][27]

Moderate Tropical Storm Edoara

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 21 – January 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

A circulation developed south of Diego Garcia on January 20, and the next was classified as a tropical disturbance by MFR. Given the name Edoara by the Mauritius Meteorological Service, it quickly intensified into a moderate tropical storm, although it never strengthened beyond winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). While maintaining a southwest track, Edoara passed southeast of Rodrigues, Mauritius, and Réunion. On Rodrigues, the storm produced wind gusts of 131 km/h (81 mph), and heavy rainfall reaching 253 mm (10.0 in) at Baie aux Huîtres. After moving away from the islands, Edoara dissipated on January 25.[1][28]

Moderate Tropical Storm Vivienne–Fanja

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 27 (entered basin) – January 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 km/h (50 mph) (10-min); 984 hPa (mbar) |

The origins of Vivienne-Fanja are unclear as a result of sparseness of data, due to a disruption in satellite imagery coverage. It is estimated that a tropical low formed on January 23 west of Christmas Island in the Australian basin. The Bureau of Meteorology named the storm Vivienne, which gradually intensified while moving to the west.[29] On January 27, the cyclone crossed 80° E into the southwest Indian Ocean, at which time it was renamed Fanja. While in the basin, the storm reached peak winds of 80 km/h (50 mph). It continued moving to the southwest before dissipating on January 30.[1][30]

Moderate Tropical Storm Galy

| Moderate tropical storm (MFR) | |

| |

| Duration | January 29 – February 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

On January 29, a circulation developed between Agaléga and Tromelin island.[1] Initially the system moved to the southwest, followed by a turn to the southeast. Given the name Galy, the storm attained winds of 65 km/h (40 mph) on January 30, but weakened into a tropical disturbance the next day. By that time, Galy turned to the west toward the Madagascar coastline, and on February 1 re-intensified into a moderate tropical storm.[31] The next day, Galy made landfall near Mananjary, but soon after recurved to the southeast and emerged into the Indian Ocean near Fort Dauphin. On February 4, the storm dissipated in a polar trough. While over land, Galy dropped light rainfall of around 44.5 mm (1.75 in).[1]

Severe Tropical Storm Haja

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 7 – February 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical depression formed on February 7 south of Diego Garcia. For about a week, the system remained weak and changed directions several times; after an eastward movement, it turned to the northwest, curved to the southeast, and later began a steady track to the southwest. On February 13, it intensified into a moderate tropical storm, and quickly attained peak winds of 95 km/h (60 mph). Given the name Haja, the storm passed southeast of Rodrigues and Réunion. Haja approached the southeast coast of Madagascar, but turned to the southeast and weakened, dissipating on February 19.[1][32]

Severe Tropical Storm Imboa

| Severe tropical storm (MFR) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 10 – February 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (10-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

On February 10, MFR began tracking a tropical disturbance in the Mozambique channel near Juan de Nova Island. The system tracked generally south-southwestward, gradually intensifying. Given the name Imboa, the storm reached peak winds of 95 km/h (60 mph) on February 13 while passing near Europa Island. After executing a small loop, Imboa turned toward the southeastern African coastline and approached the eastern coasts of Mozambique and South Africa as a weakened system. A ridge caused the storm to turn to the east and northeast, dissipating on February 19.[1][33]

Early in its duration, Imboa produced winds of 111 km/h (69 mph) at Maintirano while passing off the west coast of Madagascar.[1] While offshore South Africa, Imboa dropped heavy rainfall along the coast just weeks after Domoina flooded the region, reaching over 350 mm (14 in) in some locations. The rains caused flooding along the Mhlatuze and Mfuluzone rivers,[24] which destroyed a temporary bridge along the Umfolozi River built after Domoina.[20] Along the coast, Imboa produced high tides that caused beach erosion.[34] There were four deaths in the country.[9]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Annette–Jaminy

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 16 (entered basin) – February 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 927 hPa (mbar) |

Cyclone Annette developed simultaneously with Cyclone Willy in the Australian basin and Cyclone Haja in the south-west Indian. On February 3, a tropical low formed northeast of the Cocos Islands. Steered by a ridge to the south, it moved generally southwestward and intensified into Tropical Cyclone Annette, named by the Bureau of Meteorology. After executing a loop, Annette crossed 80 E into the south-west Indian Ocean on February 16.[29] Upon crossing into the basin, the storm was renamed Jaminy by the Mauritius Meteorological Service.[1] Around that time, the cyclone attained peak winds of 170 km/h (105 mph). Jaminy moved generally southwestward and weakened below cyclone status on February 20. The next day, it turned to the southeast, later dissipating on February 24.[35]

Intense Tropical Cyclone Kamisy

| Intense tropical cyclone (MFR) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 3 – April 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 170 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 927 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical disturbance formed near Diego Garcia on April 3 and subsequently moved westward, intensifying into a moderate tropical storm two days later. Given the name Kamisy, the storm gradually intensified into an intense tropical cyclone by April 9. Kamisy reached winds of 170 km/h (105 mph) before making landfall in extreme northern Madagascar near Diego Suarez. It weakened upon entering the Mozambique channel, but briefly re-intensified on April 10. That day while passing near Mayotte, the cyclone turned to the southeast, striking Madagascar again near Majunga. Kamisy quickly crossed the country and quickly weakened into a tropical disturbance. After emerging into the Indian Ocean off the east coast of Madagascar, the system re-intensified into a moderate tropical storm before dissipating on April 16.[1][36]

In northern Madagascar, Kamisy produced wind gusts of 250 km/h (155 mph), which destroyed 80% of the city of Diego Suarez. About 39,000 people were left homeless in the area, and there were five deaths.[1] In western Madagascar, the cyclone dropped 232.2 mm (9.14 in) of rainfall in 24 hours in Majunga, which damaged rice fields in the region after causing widespread river flooding.[1][9] The storm destroyed about 80% of Majunga where the storm struck. Throughout the country, Kamisy caused $250 million in damage and 68 deaths,[9] with 215 people injured and 100,000 left homeless.[27] Kamisy also affected Mayotte with winds of over 100 km/h (60 mph), which left about 25,000 homeless and left widespread damage.[9] One death was reported on the island.[37]

See also

Notes

- Damage totals are in 1984 United States dollars unless otherwise stated.

- The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the region.[5]

- Original currency in 1984 Malagasy francs, converted to United States dollars via FXTOP.com.[10]

- Original currency in 1989 Malagasy francs, converted to United States dollars via FXTOP.com.[11]

- Original currency in 1984 Mauritian rupees, converted to United States dollars via FXTOP.com.[16]

References

- La Météorlogie, Service de la Réunion (September 1984). "La Saison Cyclonique 1983–1984 A Madagascar" (PDF). Madagascar: Revue de Géographie (in French). 43 (Juil-Déc 1983): 146. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- Philippe Caroff; et al. (June 2011). Operational procedures of TC satellite analysis at RSMC La Reunion (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization (1983-12-01). Tropical cyclone operational plan for the South-West Indian Ocean (Report). World Meteorological Organization. ISBN 978-92-63-10618-6.

- Mark R. Jury; Beenay Pathack; Bin Wang; Mark Powell; Nirivololona Raholijao (1993). "A Destructive Cyclone Season in the SW Indian Ocean: January–February 1984" (PDF). South African Geographical Journal. University of Hawaii at Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. 95. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Archived from the original on 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 HSK0184 (1983192S05089). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 HSK0484 (1983324S08073). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Daryl (1984067S09101). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance. Annual Report for FY 1984 (PDF) (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- "Currency Converter from Malagasy Francs to United States dollars". FXTOP.com. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- "Currency Converter from Malagasy Francs to United States dollars". FXTOP.com. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Madagascar Emergency Irrigation Infrastructure Repairs Project (PDF) (Report). African Development Bank Group. January 1995. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Andry (1983339S10065). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Indradev Curpen (2013-03-01). "Louis Hervé da Sylva : "Inhabitants of Agaléga should participate in the integral development of their islands"". Le Defi Media Group. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Bakoly (1983353S08070). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- "Currency Converter from Mauritius rupees to United States dollars". FXTOP.com. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- "Quarterly Economic Review of Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, Comoros". Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (1). 1984.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Caboto (1984005S15044). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Domonia (1984016S15073). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- Dick DeAngelis (Summer 1984). "Hurricane Alley". Mariners Weather Log. United States Department of Commerce. 28 (3): 182–183.

- "Hurricane Hits Swaziland". The Spokesman-Review. 1984-01-31. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- "Swazi Storm Toll Rises to 39". The New York Times. Reuters. 1984-02-05. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (February 1984). Swaziland Floods Feb 1984 UNDRO Situation Reports 1–6 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- Z.P. Kovács; D.B. Du Plessis; P.R. Bracher; P. Dunn; G.C.L. Mallory (May 1985). Documentation of the 1984 Domoina Floods (PDF) (Report). Department of Water Affairs (South Africa). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- J.N. Rossouw (January 1985). The effects of the Domoina floods and releases from the Pongolapoort Dam on the Pongolo floodplain (PDF) (Report). Department of Water Affairs (South Africa).

- Álbaro Carmo Vaz (November 2000). Coping with Floods – The Experience of Mozambique (Report). 1st WARFSA/WaterNet Symposium: Sustainable Use of Water Resources. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (August 1993). Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide 1900–present (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Edoara (1984020S11077). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Tropical Cyclone Vivienne (Report). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Fanja:Vivienne (1984022S08086). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Galy (1984025S14073). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Haja (1984038S12073). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Imboa (1984041S17042). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Renzo Perissinotto; Derek D. Stretch; Ricky H. Taylor, eds. (2013). Ecology and Conservation of Estuarine Ecosystems: Lake St Lucia as a Global Model. New York: Cambridge University. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-107-01975-1.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Annette:Jaminy (1984035S09101). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1984 Kamisy (1984094S10080). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- "Cyclone devastates Indian Ocean islands". United Press International. 1984-04-13. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)