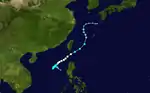

1966 Pacific typhoon season

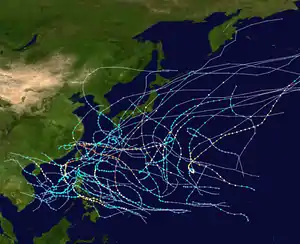

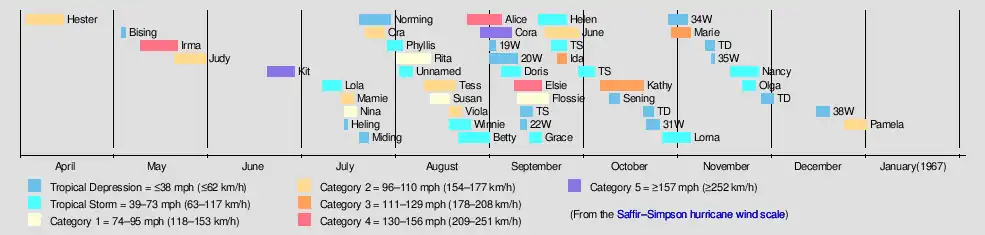

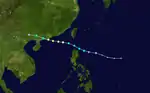

The 1966 Pacific typhoon season was an active season, with many tropical cyclones having severe impacts in China, Japan, and the Philippines. Overall, there were 49 tropical depressions declared officially or unofficially, of which 30 officially became named storms; of those, 20 reached typhoon status, while 3 further became super typhoons by having winds of at least 240 km/h (150 mph).[nb 1] Throughout the year, storms were responsible for at least 997 fatalities and $377.6 million in damage; however, a complete record of their effects is unavailable.

| 1966 Pacific typhoon season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | April 3, 1966 |

| Last system dissipated | December 31, 1966 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Kit |

| • Maximum winds | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 880 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 51 |

| Total storms | 30 |

| Typhoons | 20 |

| Super typhoons | 3 (unofficial) |

| Total fatalities | 997–1,146 total |

| Total damage | At least $377.6 million (1966 USD) |

| Related articles | |

It is widely accepted that wind estimates in the Western North Pacific during the reconnaissance era prior to 1988 are subject to great error. In many cases, intensities were grossly overestimated due to a combination inadequate technology and a lesser understanding of the mechanics behind tropical cyclones as compared to the present day. Additionally, methodologies for obtaining wind estimates have changed over the decades and is not the same today as in 1966. A joint reanalysis of typhoons from 1966 to 1987 was conducted by the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at Colorado State University and the United States Naval Research Laboratory in 2006 to correct some of these errors. Many storms in 1966 received strength reductions as a result of this study; however, the results of the research have not been implemented into the official database. Notably the number of major typhoons, Category 3-equivalent or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, was reduced from eight to six, including the removal of a Category 5.[1]

The western Pacific basin covers the Pacific Ocean, north of the equator and west of the International Date Line. Storms that form east of the date line and north of the equator are called hurricanes; see 1966 Pacific hurricane season. Tropical Storms formed in the entire west Pacific basin were assigned a name by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) also monitored systems in the basin; however, it was not recognized as the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center until 1968.[2] Tropical depressions that enter or form in the Philippine area of responsibility are assigned a name by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), which can result in the same storm having two names; in these cases both storm names are given below, with the PAGASA name in parentheses.

Systems

Typhoon Hester (Atang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 3 – April 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 979 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Irma (Klaring)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 10 – May 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

115 mph Typhoon Irma hit the eastern Samar on May 15. It weakened over the island, but re-intensified rapidly to a 140 mph typhoon in the Sibuyan Sea before hitting Mindoro on the 17th. After weakening to a tropical storm, Irma turned northward to hit western Luzon as a 95 mph typhoon on the 19th. It accelerated to the northeast, and became extratropical on the 22nd. The extratropical remnant raced northeast before abruptly slowing on May 23 well to the east of Japan. During that time, it temporarily turned north while moving erratically. The system later acquired a general eastward track by May 26 and accelerated once more before dissipating near the International Date Line on May 29.[3]

Severe damage took place across the Philippines, with Leyte suffering the brunt of Irma's impact.[4] Twenty people died across the country.[5] Preliminary reports indicated that Tacloban incurred $2.5 million in damage.[4] A gasoline explosion near Manila that killed 12 people and injured 18 others was partially attributed to the typhoon.[6] On May 17, the 740 ton vessel Pioneer Cebu sailed directly into the storm over the Visayan Sea off the coast of Malapascua Island after ignoring warnings to remain at port. Carrying 262 people, the ship struck a reef while battling rough seas in the typhoon.[4] Passengers began abandoning the sinking vessel soon thereafter under the captain's orders while message about the ship's sinking was relayed by the radio operator. A large wave then struck the ship on its side, capsizing and submerging it entirely. Of the passengers and crew, 122 went down with the ship, including captain Floro Yap, while 140 managed to escape.[7][8] Rescue operations lasted nearly two days, with many of the survivors being stranded in shark infested waters for upwards of 40 hours.[8] Of the survivors, 130 were picked up by a rescue ship while 10 others were found on nearby islands.[7] Only five bodies were recovered in the area while the rest were presumed to be lost with the ship in an area referred to as the "graveyard of ships."[8] A trading vessel, the Banca Alex, also sank off the coast of Cebu with 80 people aboard; 60 were later rescued while 20 others were never found.[9]

Typhoon Judy (Deling)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 21 – May 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

Southern Taiwan bore the brunt of Judy's impact, with gusts in the region reaching 120 km/h (75 mph).[10] The high winds cut electricity throughout the port of Kaohsiung.[11] Rainfall on the island peaked at 291.2 mm (11.46 in). A total of 18 people died while 14 were injured across the island. More than 1,000 homes sustained damage, of which 363 homes were destroyed.[12] The banana crop suffered extensive damage in southern Taiwan, with two provinces reporting 70 percent lost. Total losses to the crop reached $25 million.[10] Total damage amounted to NT$373.5 million.[12] While over the South China Sea, a U.S. Navy aircraft with four crewmen crashed in the storm. A four-day search-and-rescue mission found no trace of the men.

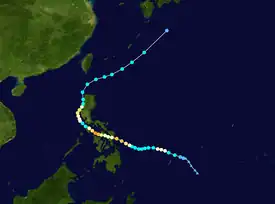

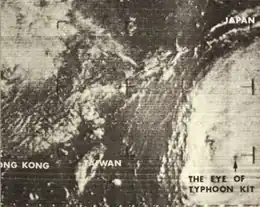

Super Typhoon Kit (Emang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 20 – June 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-min); 880 hPa (mbar) |

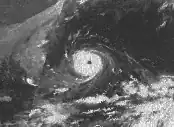

The incipient disturbance that became Super Typhoon Kit was first identified on June 20 near Chuuk State in the Federated States of Micronesia.[14] The JMA designated that system as a tropical depression that day as the system moved steadily westward.[15] The JTWC followed suit with this classification on June 22 following an investigation by reconnaissance. Early the next day, the depression acquired gale-force winds and was dubbed Tropical Storm Kit. Turning to the northwest, Kit developed a 35–55 km (22–34 mi) wide eye and reached typhoon status late on June 23.[14] Rapid intensification ensued late on June 24 into June 25; Kit's central pressure dropped 51 mbar (hPa; 1.5 inHg) in 18 hours from 965 mbar (hPa; 28.50 inHg) to 914 mbar (hPa; 26.99 inHg).[16] During this time, Kit's eye contracted to 13 to 17 km (8.1 to 10.6 mi).[14] At 06:00 UTC on June 26, the JMA estimated Kit's pressure to have abruptly dropped to 880 mbar (hPa; 25.99 inHg),[15] which would rank it among the top ten most intense tropical cyclones on record.[17] Around this time, the JTWC estimated Kit to have attained peak winds of 315 km/h (195 mph);[16][18] however, these winds are likely an overestimate.[1] A later reconnaissance mission on June 26 reported a pressure of 912 mbar (hPa; 26.93 inHg), the lowest observed in relation to the typhoon.[14] Weakening ensued thereafter as the system accelerated to the north-northeast. Retaining typhoon strength, Kit brushed southeastern Honshu, Japan, on June 28, passing roughly 155 km (96 mi) east of Tokyo. The system subsequently weakened to a tropical storm and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone south of Hokkaido on June 29.[16] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported the remnants of Kit to have dissipated the following day near northeastern Hokkaido.[19] However, the JMA states that the system turned eastward and accelerated over the north Pacific before losing its identity on July 3 near the International Date Line.[15]

Although the center of Kit remained offshore, torrential rains and damaging winds wreaked havoc in eastern Japan.[20] An estimated 510 to 760 mm (20 to 30 in) of rain fell across the region, triggering deadly landslides and floods.[21] More than 128,000 homes were affected by flooding, of which 433 collapsed.[22] Large stretches of roadway crumbled or were blocked by landslides. Additionally, service along the 480 km (300 mi) Tokyo–Osaka rail line was disrupted for 12 hours.[20] "Hip-deep" waters also shut down Tokyo's subway system, stranding an estimated 2 million people.[23][24] Throughout the country, 64 people died while a further 19 were listed missing.[22] In the aftermath of the typhoon, 25 workers died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a portable generator while repairing a damaged irrigation tunnel near Utsunomiya.[25]

Tropical Storm Lola (Gading)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 8 – July 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 992 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical depression formed near the Eastern Visayas on July 8 and tracked west-northwest. After crossing Luzon on July 11, the system emerged over the South China Sea and began strengthening.[26] Reaching tropical storm intensity on July 12, Lola tracked northwest toward Hong Kong. The system attained its peak intensity the following day with winds of 110 km/h (70 mph) and a pressure of 992 mbar (992 hPa; 29.3 inHg).[27][28] Lola subsequently made landfall near Hong Kong,[26] where it killed one person,[29] before rapidly dissipating over Guangzhou on July 14.[27]

Severe Tropical Storm Mamie (Iliang)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 14 – July 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 987 hPa (mbar) |

Severe Tropical Storm Nina

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 15 – July 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (1-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

Severe Tropical Storm Ora (Loleng)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 22 – July 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 977 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Phyllis

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 29 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 991 hPa (mbar) |

Phyllis had minor effects during the Vietnam War, briefly limiting the number of bombing raids conducted by the United States due to squally weather.[30]

Typhoon Rita

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 1 – August 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 977 hPa (mbar) |

On August 7, the vessel Almería Lykes sailed into Rita and reported peak sustained winds of 175 km/h (110 mph) and a minimum pressure of 989.2 mbar (989.2 hPa; 29.21 inHg).[31] Despite this observation, Rita is still considered a tropical storm with 110 km/h (70 mph) winds at that time.[32]

Typhoon Tess

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 10 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 972 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Tess produced tremendous rainfall across Taiwan, with Alishan receiving 1,104.8 mm (43.50 in) of rain, including 719.9 mm (28.34 in) in just 18 hours.[33][34] In contrast to the magnitude of the rain, damage was fairly limited and only one person was killed. Total losses reached NT$11.9 million with 19 homes destroyed and 9 others damaged.[12] Heavy rains also fell in mainland China with several provinces seeing several days of rain; a daily peak of 224 mm (8.8 in) was reported in Changting County. Rivers quickly over-topped their banks and flooded surrounding areas, causing widespread damage. The extent of flooding is reflected with more than 51,000 hectares (130,000 acres) of crops inundated. The Ting River crested at 5.22 m (17.1 ft), which is 1.7 m (5.6 ft) above flood-level. Throughout the affected areas, 81 people died and another 117 were injured; 12 more were listed as missing. A total of 1,384 homes were destroyed and 8,351 sustained damage.[35]

Severe Tropical Storm Susan (Oyang)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 978 hPa (mbar) |

According to the JTWC, Susan was absorbed by the nearby Typhoon Tess on August 16 while east of Taiwan.[36] However, the JMA indicates that the system continued northward as a tropical depression and ultimately dissipated near Kyushu on August 18. As such, the operationally analyzed Tropical Depression Thirteen, which supposedly formed over the East China Sea on August 17, was actually a continuation of Susan.[37][38]

Typhoon Viola

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

Owing to the weakening before landfall, Viola caused only minor damage in Japan. Offshore, three vessels capsized amid rough seas.[39]

Severe Tropical Storm Winnie

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 971 hPa (mbar) |

Severe Tropical Storm Betty

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 986 hPa (mbar) |

Super Typhoon Alice

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 240 km/h (150 mph) (1-min); 937 hPa (mbar) |

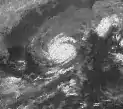

Super Typhoon Alice developed in the Western Pacific from a tropical wave on August 25. It moved to the north, looped to the west, and steadily strengthened to a peak of 150 mph. Alice continued to the west, hit eastern China on September 3, and dissipated the next day.

Across Okinawa, Alice killed one person and caused more than $10 million in damage.[40] Winds estimated at 175 km/h (110 mph) destroyed 150 homes and left 858 people homeless.[41] North of Okinawa, 13 South Korean fishing boats sank amid rough seas; 12 people perished while 26 others were listed missing.[42] Typhoon Alice produced a tremendous storm surge in Fujian Province, China, that caused widespread damage. Referred to as a "tsunami" in local media, the surge reportedly swept up to 40 km (25 mi) inland and destroyed thousands of homes, leaving an estimated 40,000 people homeless. Wind gusts up to 187 km/h (116 mph) caused significant deforestation in the region as well, with 1.7 million trees falling. Casualty statistics are unknown though believed to be significant.[35]

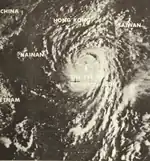

Super Typhoon Cora

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 280 km/h (175 mph) (1-min); 917 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Cora, which began its life on August 30, attained peak winds of 175 mph on September 5. It passed near Okinawa, causing major damage to the infrastructure on the island, but no loss of life. Cora continued to the northwest, hit northeastern China as a super typhoon on the 7th, and turned northeast to become extratropical near South Korea on the 9th.

Slowly moving by the southern Ryukyu Islands, Cora battered the region for more than 30 hours. Miyako-jima suffered the brunt of the typhoon's impact;[43] sustained winds on the island reached 219 km/h (136 mph) while gusts peaked at 307 km/h (191 mph).[44] This placed Cora as a greater than 1-in-100 year event in the region. Winds of least 144 km/h (89 mph) battered Miyako-jima for 13 continuous hours. Of the 11,060 homes on Miyako-jima, 1,943 were destroyed and a further 3,249 severely damaged. The majority of these were wooden structures whose structures were compromised once their roof was torn off. Steel structures also sustained considerable damage while reinforced concrete buildings fared the best.[45] The resulting effects rendered 6,000 residents homeless.[43] The scale of damage varied across the island with Ueno-mura suffering the most extensive losses. Of the community's 821 homes, 90.1 percent was severely damaged or destroyed.[45] A United States Air Force radar station was destroyed on the island.[46] On nearby Ishigaki Island, where wind gusts reached 162 km/h (101 mph), 71 homes were destroyed while a further 139 were severely damaged.[45] Total losses from Cora in the region reached $30 million. Despite the severity of damage, no fatalities took place and only five injuries were reported.[43]

Wind gusts up to 130 km/h (80 mph) caused notable damage in Taiwan,[47] with 17 homes destroyed and 42 more damaged. A smaller island closer to the storm reported a peak gust of 226 km/h (140 mph).[12] Heavy rains were generally confined to northern areas of the island,[48] peaking at 405 mm (15.9 in). Three people were killed during Cora's passage while seventeen others sustained injury.[12][47] Additionally, 5,000 persons were evacuated.[47] Damage amounted to NT$4.2 million.[12] Striking Fujian Province, China, on the heels of Typhoon Alice, Cora exacerbated damage in the region. Property damage was extreme with more than 21,000 homes destroyed and nearly 63,000 more damage. An estimated 265,000 people were severely affected by the storm. A total of 269 people perished during the storm while a further 2,918 were injured; 52 people were also listed missing. Tremendous flooding occurred as a result of the rains from Alice and Cora, damaging 190,000 hectares (470,000 acres) of crops which resulted in a loss of 195,000 kg (430,000 lb) in food production.[35]

Typhoon Doris

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 979 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Elsie (Pitang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 215 km/h (130 mph) (1-min); 943 hPa (mbar) |

Elsie's slow movement near Taiwan allowed to prolonged rainfall across the island. As a result, numerous counties saw record-breaking rains from the storm with six top-ten accumulations still holding through 2015. Yilan County saw the greatest totals from the storm with 1,076.9 mm (42.40 in) falling; this is the greatest single-storm total in the county on record.[33] Seven people were killed in Taiwan while thirty others sustained injury. A total of 120 homes collapsed while another 121 sustained damage.[12] The banana crop experienced heavy losses, with damage reaching $500,000.[49] Total losses amounted to NT$60.1 million.[12]

Typhoon Flossie

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 11 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); 963 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Grace

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 972 hPa (mbar) |

Severe Tropical Storm Helen (Ruping)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 16 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 982 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon June

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 18 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 175 km/h (110 mph) (1-min); 962 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Ida

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 22 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 961 hPa (mbar) |

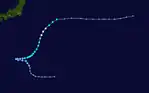

On September 21, an area of disturbed weather was noted on TIROS imagery over the open Pacific well to the east of the Mariana Islands. Following investigation by reconnaissance aircraft,[50] the system was classified as a tropical depression the following day while situated some 1,900 km (1,200 mi) southwest of Tokyo, Japan.[51] Rapid intensification soon took place as the system accelerated to the northwest. By September 23, Ida attained typhoon intensity while recon reported the formation of a 50 to 55 km (30 to 35 mi) elliptical eye.[50] Turning northward, the system reached its peak intensity early on September 24 as a Category 3–equivalent typhoon with 185 km/h (115 mph) winds.[52] Aircraft investigating the storm at this time reported a minimum pressure of 961 mbar (hPa; 28.38 inHg);[50] however, the JMA lists the system's minimum pressure as 960 mbar (960 hPa; 28 inHg).[53] The typhoon subsequently made landfall near Omaezaki, Shizuoka around 15:00 UTC at this strength.[52][53] A testament Ida's intensity, winds atop Mount Fuji gusted to 324 km/h (201 mph) during the storm's passage.[51] Once onshore, rapid structural degradation and overall weakening ensued. Less than 12 hours after striking Japan, Ida emerged over the Pacific Ocean near the Tōhoku region as a 95 km/h (60 mph), ill-defined tropical storm.[51][52] Transition into an extratropical cyclone took place shortly thereafter, with the system ultimately dissipating several hundred kilometers east of Japan on September 26.[53]

Typhoon Kathy

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 947 hPa (mbar) |

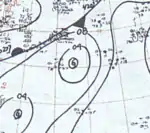

On October 6, a tropical depression was identified near Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tracking generally north-northeast, little development occurred over the following several days.[54] On October 9, the system was classified as Tropical Storm Kathy. Its motion subsequently stalled and the system executed a small clockwise loop over the following three days. Kathy quickly intensified into a typhoon late on October 9, marked by the formation of a 45 km (28 mi) wide eye.[55] The system reached an initial peak with winds of 150 km/h (95 mph) on October 10 before weakening slightly.[56] Turning northeast on October 13, Kathy began reintensifying and achieved its peak strength the following day with winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and a pressure of 947 mbar (hPa; 27.96 inHg).[55]

After maintaining its peak winds for 30 hours,[56] Kathy began to degrade. A temporary turn to the east-northeast accompanied this weakening. The system attained its secondary peak on October 18 with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph) over the open north Pacific. Approaching 40°N, cold air began to entrain into the typhoon's circulation by October 19. Transition into an extratropical cyclone south of the Aleutian Islands on October 20 as the system turned eastward. Hurricane-force winds and 9.1 m (30 ft) seas battered vessels in the region that day.[16] Weakening to gale-force, the remnant cyclone later turned north on October 23 and headed toward western Canada. The system made landfall near Queen Charlotte Island (now known as Haida Gwaii), British Columbia, on October 24 and dissipated over land.[57]

Typhoon Lorna (Titang)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 27 – November 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 990 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Marie

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 29 – November 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 946 hPa (mbar) |

Severe Tropical Storm Nancy (Uding)

| Severe tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 17 – November 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 976 hPa (mbar) |

On November 17, the JMA began monitoring a tropical depression near Yap.[58] Traveling west-northwest, the system steadily organized and reached tropical storm strength on November 19. The intensifying storm moved over the Bicol Region of the Philippines that day before striking Calabarzon at its peak with winds of 110 km/h (70 km/h).[59] Torrential rains across Luzon caused widespread damage; 32 fatalities and 14 million PHP (US$3.6 million) in losses resulted from Nancy.[60] While passing north of Manila, the cyclone slowed and turned to the southwest before emerging over the South China Sea on November 21. One ship observed winds of 95 km/h (60 mph) that day to the north of Nancy's center. Moving generally west, Nancy gradually decayed over the following five days, degrading to a tropical depression on November 25 and dissipating the following day well to the east of South Vietnam.[59]

Tropical Storm Olga (Wening)

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 21 – November 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 993 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical depression was initially identified by the JMA well to the east of the Philippines on November 21.[61] Tracking northwestward along a similar path to Nancy, the system reached tropical storm strength on November 23 about 560 km (350 mi) east of Manila. The following day, Olga brushed the northern tip of Luzon with peak winds of 85 km/h (55 mph) before turning west and moving over the South China Sea.[28][59] Subsequent interaction with a monsoon trough caused Olga to weaken and ultimately dissipate on November 25.[59]

Typhoon Pamela (Aning)

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 24 – December 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 967 hPa (mbar) |

On December 24, a tropical depression developed to the east of Palau.[62] Images from TIROS aided in locating the system on Christmas Day as it tracked west-northwest toward the Philippines. It was estimated to have become a tropical storm that day while located 350 km (220 mi) east of Samar. Pamela rapidly developed soon thereafter, with the first reconnaissance mission early on December 26 reporting it to have achieved typhoon status with a pressure of 977 mbar (977 hPa; 28.9 inHg). A 25 to 35 km (16 to 22 mi) wide eye had formed by this time. The typhoon struck northern Samar shortly after 06:00 UTC with winds of 165 km/h (105 mph).[63] Pamela was responsible for heavy damage across the central Philippines with 30 people losing their lives,[60] the majority of whom were fishermen.[64] Initial assessments were difficult due to communication loss with the four hardest-hit provinces.[65] Damage was estimated at 15 million PHP (US$6 million).[66] Interaction with land imparted weakening on the system as it moved westward.[16] Pamela made two additional landfalls at typhoon strength over Masbate and Mindoro before emerging over the South China Sea as a tropical storm. The cyclone weakened below gale-force early on December 31 and dissipated later that day to the west of South Vietnam.[62][63][67]

Other systems

In addition to the 30 named storms monitored by the JTWC throughout the year, 8 systems were warned upon that never reached gale-strength. Additionally, 11 other cyclones were warned upon by various agencies across East Asia, some of which were estimated to have reached tropical storm strength. Furthermore, disagreement on the intensity of these storms exists between the warnings centers. The table below lists the maximum intensity reported by any one agency for the sake of completeness. However, any tropical storms listed here are not considered official and thus are excluded from the season total.

| Agency/Agencies | Storm name | Dates active | Peak classification | Sustained windspeeds |

Pressure | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAGASA | Bising | May 4–5 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | [68] |

| PAGASA | Heling | July 15–16 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | [68] |

| CMA, PAGASA | Miding | July 20–23 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1002 mbar (hPa; 29.59 inHg) | [68][69] |

| CMA, PAGASA | Norming | July 20–30 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1000 mbar (hPa; 29.53 inHg) | [68][70] |

| CMA, JMA | Unnamed | August 2–6 | Tropical storm | 95 km/h (60 mph) | 996 mbar (hPa; 29.41 inHg) | [71] |

| CMA, JTWC | Nineteen | August 31 – September 2 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1001 mbar (hPa; 29.56 inHg) | [28][37][72] |

| CMA, HKO, JMA, JTWC | Twenty | August 31 – September 9 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg) | [nb 2][28][37][73] |

| CMA | Unnamed | September 10–14 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1000 mbar (hPa; 29.53 inHg) | [74] |

| JTWC | Twenty-Two | September 10–12 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) | [28][37][75] |

| CMA, JMA | Unnamed | September 20–25 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 990 mbar (hPa; 29.23 inHg) | [76] |

| CMA, JMA | Unnamed | September 29 – October 4 | Tropical storm | 95 km/h (60 mph) | 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) | [77] |

| JTWC, PAGASA | Thirty (Sening) | October 9–11 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg) | [28][37][68][78] |

| CMA, HKO | Unnamed | October 20–23 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1002 mbar (hPa; 29.59 inHg) | [79] |

| JTWC | Thirty-One | October 21–25 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1001 mbar (hPa; 29.56 inHg) | [28][37][80] |

| CMA, HKO, JMA, JTWC | Thirty-Four | October 28 – November 3 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg) | [nb 3][28][37][81] |

| CMA | Unnamed | November 9–12 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) | [82] |

| JTWC | Thirty-Five | November 11–12 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1005 mbar (hPa; 29.68 inHg) | [28][37][83] |

| CMA | Unnamed | November 27 – December 1 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) | [84] |

| CMA, JTWC, PAGASA | Thirty-Eight (Yoling) | December 15–19 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 999 mbar (hPa; 29.50 inHg) | [28][37][68][85] |

CMA: China Meteorological Agency HKO: Hong Kong Observatory | ||||||

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed in the 1966 Pacific typhoon season. It includes their names, duration, peak one-minute sustained winds, minimum barometric pressure, affected areas, damage, and death totals. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1966 USD. Names listed in parentheses were assigned by PAGASA.

| Name | Dates | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| Hester (Atang) | April 3–15 | Category 2 typhoon | 155 km/h (95 mph) | 979 mbar (hPa; 28.91 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][68] |

| Irma (Klaring) | May 10–22 | Category 4 typhoon | 220 km/h (135 mph) | 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg) | Philippines | $2.5 million | 174 | [5][6][7][8][9][28][68] |

| Judy (Deling) | May 21–31 | Category 2 typhoon | 155 km/h (95 mph) | 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg) | Taiwan | $25 million | 22 | [12][28][68] |

| Kit (Emang) | June 20–29 | Category 5 super typhoon | 315 km/h (195 mph) | 912 mbar (hPa; 26.93 inHg) | Japan | N/A | 89–108 | [22][25][28][68] |

| Lola (Gading) | July 8–14 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 992 mbar (hPa; 29.29 inHg) | Philippines, China, Hong Kong | N/A | 1 | [28][29][68] |

| Mamie (Iliang) | July 14–18 | Category 2 typhoon | 155 km/h (95 mph) | 987 mbar (hPa; 29.15 inHg) | China | N/A | N/A | [28][68] |

| Nina | July 15–19 | Category 1 typhoon | 120 km/h (75 mph) | 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Ora (Loleng) | July 22–28 | Category 2 typhoon | 155 km/h (95 mph) | 977 mbar (hPa; 28.85 inHg) | China, Vietnam | N/A | N/A | [28][68] |

| Phyllis | July 29 – August 3 | Tropical storm | 85 km/h (55 mph) | 991 mbar (hPa; 29.26 inHg) | Vietnam | N/A | N/A | [28] |

| Rita | August 1–12 | Category 1 typhoon | 150 km/h (95 mph) | 977 mbar (hPa; 28.85 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Tess | August 10–20 | Category 2 typhoon | 165 km/h (105 mph) | 972 mbar (hPa; 28.70 inHg) | Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan China | N/A | 82–94 | [12][28][35] |

| Susan (Oyang) | August 12–18 | Category 1 typhoon | 150 km/h (95 mph) | 978 mbar (hPa; 28.88 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][68] |

| Viola | August 18–22 | Category 2 typhoon | 165 km/h (105 mph) | 975 mbar (hPa; 28.79 inHg) | Japan | N/A | N/A | [28] |

| Winnie | August 18–25 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 971 mbar (hPa; 28.67 inHg) | Japan, Korean Peninsula, China, Soviet Union | N/A | N/A | [28] |

| Betty | August 21–31 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 986 mbar (hPa; 29.12 inHg) | Japan, Korean Peninsula | N/A | N/A | |

| Alice | August 24 – September 4 | Category 4 super typhoon | 240 km/h (150 mph) | 937 mbar (hPa; 27.67 inHg) | Ryukyu Islands, China | $10 million | 13–39 | [28][40][42] |

| Cora | August 28 – September 7 | Category 5 super typhoon | 280 km/h (175 mph) | 917 mbar (hPa; 27.08 inHg) | Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, China, Korean Peninsula | $30 million | 272–324 | [12][28][35][43] |

| Nineteen | August 31 – September 2 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1000 mbar (hPa; 29.53 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][72] |

| Twenty | August 31 – September 9 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][73] |

| Doris | September 4–10 | Tropical storm | 95 km/h (60 mph) | 979 mbar (hPa; 28.91 inHg) | Japan | N/A | N/A | [28] |

| Elsie (Pitang) | September 8–17 | Category 4 typhoon | 215 km/h (135 mph) | 943 mbar (hPa; 27.85 inHg) | Taiwan, Ryukyu Islands | $500,000 | 7 | [12][28][49][68] |

| Flossie | September 9–18 | Category 1 typhoon | 140 km/h (85 mph) | 963 mbar (hPa; 28.44 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Twenty-Two | September 10–12 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 1004 mbar (hPa; 29.65 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][75] |

| Grace | September 13–17 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 972 mbar (hPa; 28.70 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Helen (Ruping) | September 16–25 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 982 mbar (hPa; 29.00 inHg) | Japan | N/A | N/A | [nb 4][28][68] |

| June | September 18–29 | Category 2 typhoon | 175 km/h (110 mph) | 962 mbar (hPa; 28.41 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Ida | September 22–25 | Category 3 typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 961 mbar (hPa; 28.38 inHg) | Japan | $300 million | 275–318 | [28][51][86] |

| Kathy | October 6–20 | Category 3 typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 947 mbar (hPa; 27.96 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Thirty (Sening) | October 9–12 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 998 mbar (hPa; 29.47 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][68][78] |

| Thirty-One | October 21–25 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1001 mbar (hPa; 29.56 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][80] |

| Lorna (Titang) | October 26 – November 4 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 990 mbar (hPa; 29.23 inHg) | Philippines | N/A | N/A | [68] |

| Thirty-Four | October 28 – November 3 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg) | None | None | None | [28][37][81] |

| Marie | October 29 – November 4 | Category 3 typhoon | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 946 mbar (hPa; 27.94 inHg) | None | None | None | [28] |

| Thirty-Five | November 11–12 | Tropical depression | 45 km/h (30 mph) | 1005 mbar (hPa; 29.68 inHg) | Vietnam | None | None | [28][37][83] |

| Nancy (Uding) | November 17–26 | Tropical storm | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 976 mbar (hPa; 28.82 inHg) | Philippines | $3.6 million | 32 | [28][60][68] |

| Olga (Wening) | November 21–25 | Tropical storm | 85 km/h (55 mph) | 993 mbar (hPa; 29.32 inHg) | Philippines | N/A | N/A | [28][68] |

| Thirty-Eight (Yoling) | December 15–19 | Tropical depression | 55 km/h (35 mph) | 999 mbar (hPa; 29.50 inHg) | Philippines | None | None | [28][37][68][85] |

| Pamela (Aning) | December 24–31 | Category 2 typhoon | 165 km/h (105 mph) | 967 mbar (hPa; 28.56 inHg) | Philippines | $6 million | 30 | [28][60][66][68] |

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 38 systems | April 6 – December 31, 1966 | 315 km/h (195 mph) | 912 mbar (hPa; 26.93 inHg) | >$378 million | 997–1,146 | |||

See also

- 1966 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1966 Pacific hurricane season

- Australian cyclone seasons: 1965–66, 1966–67

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1965–66, 1966–67

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1965–66, 1966–67

Notes

- All winds are one-minute sustained unless otherwise noted

- This system is considered a tropical storm with peak winds of 75 km/h (45 mph) and a minimum pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg) by the China Meteorological Agency, Hong Kong Observatory, and Japan Meteorological Agency.[73]

- This system is considered a tropical storm with peak winds of 75 km/h (45 mph) and a minimum pressure of 995 mbar (hPa; 29.38 inHg) by the China Meteorological Agency, Hong Kong Observatory, and Japan Meteorological Agency.[81]

- The quick succession of Tropical Storm Helen and Typhoon Ida in Japan made differentiating damage impossible. Their combined effects are included within Ida's listing.

References

- John A. Knaff; Charles R. Sampson (2006). "Reanalysis of West Pacific Tropical Cyclone Maximum Intensity 1966–1987" (PDF). American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "Japan Meteorological Agency Services: International Cooperation". Japan Meteorological Agency. 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- Patrick E. Hughes, ed. (November 1966). "Tracks of Centers of Cyclones at Sea Level, North Pacific: May 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 10 (6): 213.

- "Fear Typhoon Sinks Vessel; 262 Missing". Chicago Tribune. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. May 18, 1966. p. 45. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "Week In Review: Typhoon Irma". Independent Press-Telegram. May 22, 1966. p. 99. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Gas Leak, Typhoon Bring Death To Twelve". Las Cruces Sun-News. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. May 22, 1966. p. 2. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Around The World". The Daily Reporter. Manila, Philippines. May 20, 1966. p. 10. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Tell Horror of Ship Sinking in Typhoon". Chicago Tribune. Manila, Philippines. United Press International. May 19, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "60 Survivors Saved, 20 Missing Off Cebu". The Bridgeport Post. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. May 23, 1966. p. 55. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Around The World: Taipei". El Paso Herald-Post. Taipei, Taiwan. June 2, 1966. p. 2. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Judy Leaves Formosa". The Winona Daily News. Taipei, Taiwan. Associated Press. June 8, 1966. p. 19. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- 侵臺颱風綱要表 (1897~2008) (in Chinese). 中央氣象局. February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "Chapter V: Individual Tropical Cyclones in 1966: Typhoon Kit" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 102–108. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Typhoon 196604 (Kit) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. October 17, 1990. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Frank P. Rossi, ed. (May 1967). "Typhoons of the Western North Pacific, 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 11 (3): 75–82.

- "Typhoon List by Lowest Central Pressure: 870 hPa to 895 hPa". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Super Typhoon 4 (Kit) Best Track" (.TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1967. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Patrick E. Hughes, ed. (November 1966). "Tracks of Centers of Cyclones at Sea Level, North Pacific: June 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 10 (6): 215.

- "Typhoon Kit Takes 52 Lives". Mt. Vernon Register-News. Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. June 29, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Kit kills 38". The Oneonta Star. Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. July 1, 1966. p. 13. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "台風196604号 (Kit) – 災害情報" (in Japanese). 国立情報学研究所. 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "Typhoon Kit Dies Down After Killing Over 50". The Index-Journal. Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. June 29, 1966. p. 32. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Hip-Deep Water". The Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. July 1, 1966. p. 4. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Death of 25 Blamed On Monoxide Exhaust". Albuquerque Journal. Utsunomiya, Japan. United Press International. July 10, 1966. p. 63. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon 196605 (Lola) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. June 1, 1989. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Patrick E. Hughes, ed. (September 1966). "Marine Weather Review: Rough Log, North Pacific Weather, May–July 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 10 (5): 185–193.

- "Chapter IV: Summary of Tropical Cyclones in 1966: 1966 Tropical Cyclones" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 67–68. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Casualties and Damage Caused by Tropical Cyclones in Hong Kong since 1960". Hong Kong Observatory. January 21, 2014. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Weather Limits Raids". The Daily Telegram. August 3, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- Frank P. Rossi, ed. (January 1967). "Selected Gale Observations, North Pacific: July and August 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 11 (1): 39.

- "Typhoon 10 (Rita) Best Track" (.TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1967. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- 測站最大總雨量值統計前10名 (in Chinese). 中央氣象局. 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- 測站最大18小時雨量值統計前10名 (in Chinese). 中央氣象局. 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- 1966年秋天登陆福建的台风 (in Chinese). 台风论坛. June 15, 2012.

- Frank P. Rossi, ed. (January 1967). "Marine Weather Review: Smooth Log, North Pacific Weather, July and August 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 11 (1): 22–29.

- "Chapter IV: Tropical Depression Position Data" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 74–75. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 13W:Susan (1966223N16118). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Warning Typhoon Viola Brings Rain to Japan". The Circleville Herald. Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. August 22, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Alice Rakes Okinawa". Cumberland Evening Times. Naha, Okinawa. United Press International. September 2, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Alice Slams Okinawa". Idaho Free Press. Naha, Okinawa. United Press International. September 2, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "World News Capsules: Naha, Okinawa". The Sedalia Democrat. Naha, Okinawa. Associated Press. September 4, 1966. p. 7. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Island Storm Damage Set at $30 million". The Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Naha, Okinawa. Associated Press. September 8, 1966. p. 9. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- 第2宮古島台風 (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- Hatsuo Ishizaki; Junji Katsura; Tatsuo Murota (May 1968). "The Damage To Structures Caused By The Second Miyakojima Typhoon" (PDF). Bulletin of the Disaster Prevention Research Institute. 18 (1). Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- "Typhoon Knocks Out Radar Post". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Tokyo, Japan. Associated Press. September 7, 1966. p. 1. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- "Storm Kills Formosa Resident, 17 Injured". Anderson Herald. Taipei, Taiwan. United Press International. September 8, 1966. p. 14. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- 1966 年寇拉(Cora)颱風 (PDF) (Report) (in Chinese). 中央氣象局. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "Typhoon Elsie Scythes Formosa Banana Crop". The Bridgeport Telegram. Taipei, Taiwan. Associated Press. September 19, 1966. p. 7. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Chapter V: Individual Tropical Cyclones in 1966: Typhoon Ida" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 186–191. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Patrick E. Hughes, ed. (November 1966). "Marine Weather Review: Rough Log, North Pacific Weather, July–September 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 10 (6): 226.

- "Typhoon 23 (Ida) Best Track" (.TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1967. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "Typhoon 196626 (Ida) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. June 1, 1989. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- "Typhoon 196629 (Kathy) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. July 16, 1991. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Chapter V: Individual Tropical Cyclones in 1966: Typhoon Kathy" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 200–209. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Typhoon 25 (Kathy) Best Track" (.TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1967. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Frank P. Rossi, ed. (January 1967). "Marine Weather Review: Rough Log, North Pacific Weather, September–November 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 11 (1): 32–40.

- "Typhoon 196633 (Nancy) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. June 1, 1989. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Frank P. Rossi, ed. (May 1967). "Smooth Log, North Pacific Weather: November and December 1966". Mariners Weather Log. Washington, D.C. 11 (3): 100–107.

- "Tropical Cyclone Disasters in the Philippines: A Listing of Major Typhoons by Month Through 1979" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. Office of United States Foreign Disaster Assistance. 1980. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- "Typhoon 196634 (Olga) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. June 1, 1989. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Typhoon 196635 (Pamela) – Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. March 19, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Chapter V: Individual Tropical Cyclones in 1966: Typhoon Pamela" (PDF). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1967. pp. 215–220. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- "Typhoon Toll Hits 30 In Philippines". The Charleston Daily Mail. Manila, Philippines. Associated Press. December 30, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Pamela Blows Out To Sea". Eureka Humboldt Standard. Manila, Philippines. United Press International. December 28, 1966. p. 1. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Cuts A Wicked Path". Daily Independent Journal. Manila, Philippines. United Press International. December 29, 1966. p. 25. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Pamela (1966358N07139). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- Michael V. Pauda (June 11, 2008). "PAGASA Tropical Cyclones 1963–1988 [within the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR)]" (.TXT). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966201N08133). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966201N21156). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966215N20163). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 19W (1966243N12112). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 20W:TS0905 (1966244N18165). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966253N22133). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 22W (1966254N15149). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966263N19149). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966272N23138). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 30W (1966282N12132). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966294N09115). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 31W (1966265N12111). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 34W:TS1031 (1966302N10161). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966313N18120). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 35W (1966315N15111). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 Missing (1966331N13130). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1966 38W (1966349N09149). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- "台風196626号 (Ida) – 災害情報" (in Japanese). 国立情報学研究所. 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

External links

- The Joint Typhoon Warning Center's Annual Tropical Cyclone Report for the 1966 season

- (in Chinese) The Central Weather Bureau's report on the 1966 season