Repentance in Judaism

Repentance (/tʃuvɑː/; Hebrew: תשובה, romanized: tǝshuvā "return") is one element of atoning for sin in Judaism. Judaism recognizes that everybody sins on occasion, but that people can stop or minimize those occasions in the future by repenting for past transgressions. Thus, the primary purpose of repentance in Judaism is ethical self-transformation.[1]

| Repentance in Judaism Teshuva "Return" |

|---|

|

Repentance, atonement and higher ascent in Judaism |

|

|

| In the Hebrew Bible |

| Aspects |

| In the Jewish calendar |

| In contemporary Judaism |

A Jewish penitent is traditionally known as a baal teshuva.

Repentance and creation

According to the Talmud, God created repentance before He created the physical universe, making it among the first things created.[2]

When to repent

One should repent immediately. A parable is told in the Talmud that Rabbi Eliezer taught his disciples, "Repent one day before your death." The disciples politely questioned whether one can know the day of one's death, so Rabbi Eliezer answered, "All the more reason, therefore, to repent today, lest one die tomorrow."[3]

Because of Judaism's understanding of the annual process of Divine Judgment, Jews believe that God is especially open to repentance during the period from the beginning of the month of Elul through the High Holiday season, i.e., Rosh HaShanah (the Day of Judgement), Ten Days of Repentance, Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), and, according to Kabbalah, Hoshana Rabbah. Another good time to repent is toward the end of one's life.[1] Another occasion on which forgiveness is granted is whenever the entire community gathers and cries out to God full-heartedly due to their distress.[4]

How to repent

Numerous guides to the repentance process can be found in rabbinical literature. See especially Maimonides' Rules of Repentance in the Mishneh Torah.

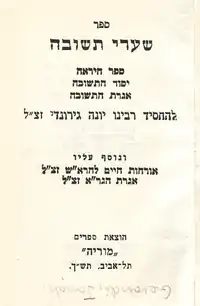

According to Gates of Repentance, a standard work of Jewish ethics written by Rabbenu Yonah of Gerona, a sinner repents by:[5]

- regretting/acknowledging the sin;

- forsaking the sin (see below);

- worrying about the future consequences of the sin;

- acting and speaking with humility;

- acting in a way opposite to that of the sin (for example, for the sin of lying, one should speak the truth);

- understanding the magnitude of the sin;

- refraining from lesser sins for the purpose of safeguarding oneself against committing greater sins;

- confessing the sin;

- praying for atonement;

- correcting the sin however possible (for example, if one stole an object, the stolen item must be returned; or, if one slanders another, the slanderer must ask the injured party for forgiveness);

- pursuing works of chesed and truth;

- remembering the sin for the rest of one's life;[6]

- refraining from committing the same sin if the opportunity presents itself again;

- teaching others not to sin.

Forsaking the sin

The second of Rabbenu Yonah's "Principles of Repentance" is "forsaking the sin" (Hebrew: עזיבת–החטא, azivat-hachet). After regretting the sin (Rabbenu Yonah's first principle), the penitent must resolve never to repeat the sin.[7] However, Judaism recognizes that the process of repentance varies from penitent to penitent and from sin to sin. For example, a non-habitual sinner often feels the sting of the sin more acutely than the habitual sinner. Therefore, a non-habitual sinner will have an easier time repenting, because he or she will be less likely to repeat the sinful behavior.[8]

The case of the habitual sinner is more complex. If the habitual sinner regrets his or her sin at all, that regret alone clearly does not translate into a change in behavior. In such a case, Rabbi Nosson Scherman recommends devising "a personal system of reward and punishment" and avoiding circumstances that may cause temptation toward the relevant sin.[8] One is shown to have fully repented if they are presented with an opportunity to perform the same sin under the same conditions, yet they manage to refrain from doing so.[9]

Effects

The Talmud debates the spiritual level of a person who has repented (a baal teshuvah). According to one opinion, this level is lower than that of a "fully righteous" person who has never sinned. According to another opinion, though, it is even higher than that of a fully righteous person.[10]

The Talmud makes two statements about the power of repentance to transform one's past sins: If one repents out of fear, the intentional sins are turned into unintentional sins. But if one repents out of love, the intentional sins actually become merits.[11] The first statement can be easily understood, in that if one committed the sin unaware of its consequences (e.g. punishment), and subsequently becomes aware, the sin was committed in a state of incomplete knowledge. The second statement is harder to understand, and different interpretations have been suggested. According to Joseph Dov Soloveitchik, the meaning is that a person who repents out of love embarks on a journey of self-transformation, in which they use the pain of their failure as a spur to self-improvement. Thus, the magnitude of the original sin is eventually reflected in the magnitude of the good traits which the penitent develops in response.[12]

Examples

- In 609 BCE King Josiah of Israel was killed in battle by Pharaoh Necho II; Josiah's death was brought about because, despite his sincere religious reform, he had in fact been deceived as the people did not follow his reforms; thus he refused to heed the Prophet Jeremiah, thinking that no sword would pass through the Land of Israel. He was struck by 300 darts; he made no complaint except to acknowledge "The Lord is righteous, for I rebelled against His commandment.[13]

- After Passover in CE 44, Herod Agrippa went to Caesarea, where he had games performed in honor of Claudius. In the midst of his speech to the public, a cry went out that he was a god, and Agrippa did not then publicly react. At this time he saw an owl perched over his head. During his imprisonment by Tiberius, a similar omen had been interpreted as portending his speedy release and future kingship, with the warning that should he behold the same sight again, he would die.[14] He was immediately smitten with violent pains, scolded his friends for flattering him, and accepted his imminent death in a state of Teshuva. He experienced heart pains and pain in his abdomen and died after five days.[15]

See also

- Baal teshuva

- Baal teshuva movement

- Elul

- Forgiveness

- Jewish Ethics

- Orthodox Jewish outreach

- Tawbah, a similar concept in Islam

- Penance, a similar concept in Christianity

References

- Telushkin, Joseph. A Code of Jewish Ethics: Volume 1 - You Shall Be Holy. New York: Bell Tower, 2006. p. 152-173.

- Nedarim 39b

- Shabbat 153a; quoted in Telushkin, 155

- Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuvah 2:6

- Yonah Ben Avraham of Gerona. Shaarei Teshuva: The Gates of Repentance. Trans. Shraga Silverstein. Jerusalem, Israel: Feldheim Publishers, 1971. Print.

- Thus, “He guards Lovingkindness for thousands”— even though a person has sinned thousands of times and made thousands of blemishes, God can and will forgive him, i.e. all sins (if he repents) (Rebbe Nachman of Breslov. Likutey Halakhot I, p. 1b)

- Yonah, 14-15

- Nosson Scherman. "An Overview - Day of Atonement and Purity." An Overview. The Complete ArtScroll Machzor: Yom Kippur. By Scherman. Trans. Scherman. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 2008. XIV-XXII.

- Yoma 86b; Maimonides "Laws of Repentance" 2:1

- Berakhot 34b

- Yoma 86b

- גדולה תשובה - זדונות כזכויות

- Ginzberg, Louis; Cohen, Boaz (January 8, 1913). "The Legends of the Jews". Jewish publication society of America – via Google Books.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Agrippa, Herod, I.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 425.

- Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae xix. 345–350 (Chapter 8 para 2)

- Theological dictionary of the Old Testament: Vol.14 p473 G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, Heinz-Josef Fabry - 2004 "The noun t'suba occurs 4 times in the Dtr History, twice in the Chronicler's History and in Job."

- Jacob J. Petuchowski, The Concept of 'Teshuva' in the Bible and Talmud, Judaism 17 (1968), 175–185.