Tucker Act

The Tucker Act (March 3, 1887, ch. 359, 24 Stat. 505, 28 U.S.C. § 1491) is a federal statute of the United States by which the United States government has waived its sovereign immunity with respect to certain lawsuits.

The Tucker Act may be divided into the "Big" Tucker Act, which applies to claims above $10,000 and gives jurisdiction to the United States Court of Federal Claims, and the "Little" Tucker Act (28 U.S.C. § 1346), the current version of which gives concurrent jurisdiction to the Court of Federal Claims and the District Courts "for the recovery of any internal-revenue tax alleged to have been erroneously or illegally assessed or collected, or any penalty claimed to have been collected without authority or any sum alleged to have been excessive or in any manner wrongfully collected under the internal-revenue laws", and for claims below $10,000.[1]

Permitted lawsuits

Suits may arise out of express or implied contracts to which the government was a party. Damages may be liquidated or unliquidated. Suits may be brought for Constitutional claims, particularly taking of property by the government to be compensated under the Fifth Amendment. Parties may bring suit for a refund of taxes paid. Explicitly excluded are suits in which a claim is based on a tort by the government.

The Tucker Act granted jurisdiction to the Court of Claims over government contract money claims both for breach, and for relief under the contracts in the form of equitable adjustment. Claims against the government for breach of contract do not compromise the government's sovereign immunity, so the government cannot be held liable for failure to comply with a contractual obligation because of the exercise of its duties as a sovereign: "the two characters which the government possesses as a contractor and as a sovereign cannot be ... fused".[2]

As an alternative to proceeding directly against the United States pursuant to the Tucker Act, the Supreme Court, in Burr v. FHA,[3] has stated that Congress may organize "sue and be sued" agencies; such agencies may be sued in any court of otherwise competent jurisdiction as if it were a private litigant, as long as the agency is to pay out the judgment from its own budget, not from the U.S. Treasury. Whether the agency or the Treasury is to pay depends on the congressional intent.

The Tucker Act in itself does not create any substantive rights, but must be paired with a "money mandating" statute that allows for the payment of money, per the Supreme Court decision in United States v. Testan.[4]

Wunderlich Act

In United States v. Wunderlich (1951), the Supreme Court held that procurement agencies could preclude judicial review of their decisions relating to contract disputes (except as to fraud issues) by exacting the contractor's acquiescence in contract clauses making agency board's decisions final both as to fact and law. This result was not deemed desirable by Congress, which enacted the Wunderlich Act to overturn that decision. Under the terms of this Act, board decisions could be accorded no finality on questions of law, but findings could be made final as to fact issues so far as supported by substantial evidence and not arbitrary or capricious, etc., and thus the statute restored a significant role to the Court of Claims.

Under the Wunderlich Act, the Court of Claims at first received testimony additional to that in the board record, determining whether board findings were supported by substantial evidence by weighing the findings against both record testimony and that newly taken. In United States v. Carlo Bianchi & Co.[5] in 1963, the Supreme Court construed the Wunderlich Act to restrict the Court of Claims to a purely appellate function in disputes clause cases. The court could remand to the board for further testimony, if needed, but could not take any itself, nor make any fact findings.

The Court of Claims at that period, besides the Article III judges, included several persons called "commissioners" in the rules; later they were called "trial judges" and, collectively, the court's "trial division". The Bianchi decision appeared to eliminate any function for these commissioners to perform as to most contract disputes clause cases, for they were primarily takers of testimony and fact finders. However, the judges, having found the commissioners' services of value, were reluctant to dispense with them, and a way to utilize them was found. The rules were amended for Wunderlich cases only, Ct. Cl. Rule 163(b),[6] to provide that in such cases both parties should file motions for summary judgment, which motions were referred to commissioners for advisory or recommended opinions. That there was no fact issue requiring trial was a conclusion forced by Bianchi. The commissioners usually reviewed the records, received briefs, and heard oral arguments. In other than Wunderlich cases, cross-motions for summary judgment went before the Article III judges with no participation by the commissioners. In Wunderlich cases, the recommended opinion of the commissioner was, unless acquiesced in by both parties, considered on exceptions, oral arguments, and new briefs by the Article III judges.

History

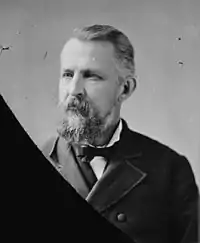

The Act was named after Congressman John Randolph Tucker, of Virginia, who introduced it as a substitute for four other competing measures on government claims being considered by the House Judiciary Committee.

References

- "Litigation Against the Government". Federal Practice Manual for Legal Aid Attorneys. Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- Sanford, E. T., Horowitz v. United States/Opinion of the Court, United States Supreme Court, 267 US 458 (1925), accessed 1 August 2023, citing Jones v. United States, 1 Ct. Cl. 383, 384, and also Deming v. United States, 1 Ct. Cl. 190, 191 and Wilson v. United States, 11 Ct. Cl. 513, 520

- Burr v. FHA, 309 U.S. 242 (1940)

- United States v. Testan, 424 U.S. 392 (1976)

- United States v. Bianchi & Co. 373 U.S. 709 (1963)

- Rules of the United States Court of Claims, 1969 ed., p. 93