Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some scholars only consider the 11th and 12th dynasties to be part of the Middle Kingdom.

Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 BC – 1802 BC | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Thebes, Itjtawy | ||||||||

| Common languages | Egyptian language | ||||||||

| Religion | ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | 1991 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1802 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

|

See also: List of pharaohs by period and dynasty Periodization of ancient Egypt |

History

The chronology of the Twelfth Dynasty is the most stable of any period before the New Kingdom. The Turin Royal Canon gives 213 years (1991–1778 BC). Manetho stated that it was based in Thebes, but from contemporary records it is clear that the first king of this dynasty, Amenemhat I, moved its capital to a new city named "Amenemhat-itj-tawy" ("Amenemhat the Seizer of the Two Lands"), more simply called, Itjtawy.[1] The location of Itjtawy has not been discovered yet, but is thought to be near the Fayyum, probably near the royal graveyards at el-Lisht.[2]

The order of its rulers of the Twelfth Dynasty is well known from several sources: two lists recorded at temples in Abydos and one at Saqqara, as well as lists derived from Manetho's work. A recorded date during the reign of Senusret III can be correlated to the Sothic cycle,[3] consequently, many events during this dynasty frequently can be assigned to a specific year.

The Prophecy of Neferti from the period mention Amenemhat I's mother being from[4] the Elephantine Egyptian nome Ta-Seti.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Many scholars in recent years have argued that Amenemhat I's mother was of Nubian origin.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

Rulers

| Name | Horus (throne) name | Image | Date | Pyramid | Queen(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amenemhat I | Sehetepibre |  | 1991 – 1962 BC | Pyramid of Amenemhet I | Neferitatjenen |

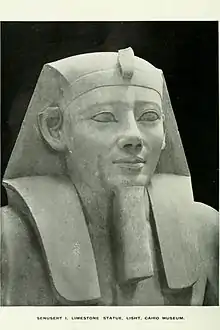

| Senusret I (Sesostris I) | Kheperkare |  | 1971 – 1926 BC | Pyramid of Senusret I | Neferu III |

| Amenemhat II | Nubkhaure |  | 1929 – 1895 BC | White Pyramid | Kaneferu Keminub? |

| Senusret II (Sesostris II) | Khakheperre | .jpg.webp) | 1897 – 1878 BC | Pyramid at El-Lahun | Khenemetneferhedjet I Nofret II Itaweret? Khnemet |

| Senusret III (Sesostris III) | Khakaure |  | 1878 – 1839 BC | Pyramid at Dahshur | Meretseger Neferthenut Khnemetneferhedjet II (Weret) Sithathoriunet |

| Amenemhat III | Nimaatre |  | 1860 – 1814 BC | Black Pyramid; Pyramid at Hawara | Aat Hetepi Khenemetneferhedjet III |

| Amenemhat IV | Maakherure | -BritishMuseum-August19-08.jpg.webp) | 1815 – 1806 BC | Southern Mazghuna pyramid (conjectural) | |

| Sobekneferu | Sobekkare | .jpg.webp) | 1806 – 1802 BC | Northern Mazghuna pyramid (conjectural) |

Known rulers of the Twelfth Dynasty are as follows:[20]

Amenemhat I

This dynasty was founded by Amenemhat I, who may have been vizier to the last king of Dynasty XI, Mentuhotep IV. His armies campaigned south as far as the Second Cataract of the Nile and into southern Canaan. He also reestablished diplomatic relations with the Canaanite state of Byblos and Hellenic rulers in the Aegean Sea. He was the father of Senusret I.

Senusret I

Senusret I followed his father's triumphs with an expedition south to the Third Cataract.

Amenemhat II

Amenemhat II was king during a very peaceful time.

Senusret II

Senusret II also was content to live in peace.

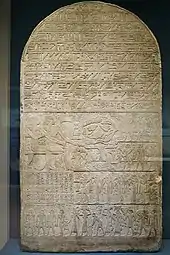

.jpg.webp)

Senusret III

Finding Nubia had grown restive under the previous rulers, Senusret sent punitive expeditions into that land. He also sent an expedition into the Levant. His military campaigns gave birth to a legend of a mighty warrior named Sesostris, a story retold by Manetho, Herodotus, and Diodorus Siculus. Manetho claimed the mythical Sesostris not only subdued the lands as had Senusret I, but also conquered parts of Canaan and had crossed over into Europe to annex Thrace. However, there are no records of the time, either in Egyptian or other contemporary writings that confirm Manetho's additional claims.

Amenemhat III

Senusret's successor Amenemhat III reaffirmed his predecessor's foreign policy. However, after Amenemhat, the energies of this dynasty were largely spent, and the growing troubles of government were left to the dynasty's last ruler, Sobekneferu, to resolve. Amenemhat was remembered for the mortuary temple at Hawara that he built, known to Herodotus, Diodorus, and Strabo as the "Labyrinth". Additionally, under his reign, the marshy Fayyum was first exploited.

Amenemhat IV

Amenemhat IV succeeded his father, Amenemhat III, and ruled for approximately nine years.

Sobekneferu

Sobekneferu, a daughter of Amenemhat III, was left with the unresolved governmental issues that are noted as arising during her father's reign when she succeeded Amenemhat IV, thought to be her brother, half brother, or step brother.[22] Upon his death, she became the heir to the throne because her older sister, Neferuptah, who would have been the next in line to rule, died at an early age. Sobekneferu was the last king of the twelfth dynasty. There is no record of her having an heir. She also had a relatively short reign and the next dynasty began with a shift in succession, possibly to unrelated heirs of Amenemhat IV.[23]

Ancient Egyptian literature refined

It was during the twelfth dynasty that Ancient Egyptian literature was refined. Perhaps the best known work from this period is The Story of Sinuhe, of which several hundred papyrus copies have been recovered. Also written during this dynasty were a number of didactic works, such as the Instructions of Amenemhat and The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant.

Also, the kings of dynasties twelve through eighteen are credited with preserving for posterity some of the most remarkable Egyptian papyri that have survived to today:

- 1900 BC – Prisse Papyrus

- 1800 BC – Berlin Papyrus

- 1800 BC – Moscow Mathematical Papyrus

- 1650 BC – Rhind Mathematical Papyrus

- 1600 BC – Edwin Smith papyrus

- 1550 BC – Ebers papyrus

See also

References

- Arnold, Dorothea (1991). "Amenemhat I and the Early Twelfth Dynasty at Thebes". Metropolitan Museum Journal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 26: 5–48. doi:10.2307/1512902. JSTOR 1512902. S2CID 191398579.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2000). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Parker, Richard A., "The Sothic Dating of the Twelfth and Eighteenth Dynasties," in Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, 1977

- "Then a king will come from the South, Ameny, the justified, by name, son of a woman of Ta-seti, child of Upper Egypt""The Beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty". Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge University Press: 138–160. 2020. doi:10.1017/9781108914529.006. ISBN 9781108914529. S2CID 242213167.

- "Ammenemes himself was not a Theban but the son of a woman from Elephantine called Nofret and a priest called Sesostris (‘The man of the Great Goddess’).",Grimal, Nicolas (1994). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell (July 19, 1994). p. 159.

- "Senusret, a commoner as the father of Amenemhet, his mother, Nefert, came from the area Elephantine."A. Clayton, Peter (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 78.

- "Amenemhet I was a commoner, the son of one Sen- wosret and a woman named NEFRET, listed as prominent members of a family from ELEPHANTINE Island."Bunson, Margaret (2002). Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt (Facts on File Library of World History). Facts on File. p. 25.

- "In a literary source, The Prophecy of Neferty, the origin of the king from the common people of Upper

Egypt with a mother from the very south of Egypt"Arnold, Dorothea (1991). "Amenemhat I and the Early Twelfth Dynasty at Thebes". Metropolitan Museum Journal, v. 26 (1991): 18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "This opens up several questions about the role of the elite families of Elephantine at the end of the First Intermediate Period and the beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty, especially taking into account that Amenemhat I’s mother came from that region, according to the Prophecy of Neferti"JIMÉNEZ SERRANO, ALEJANDRO; CARLOS SÁNCHEZ LEÓN, JUAN (2015). "A FORGOTTEN GOVERNOR OF ELEPHANTINE DURING THE TWELFTH DYNASTY: AMENY*". THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY: 129.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "but also openly admitted the king’s humble origin. Without mentioning her name, Neferti simply stated that the king’s mother was a woman from the first Upper Egyptian nome (tA-sty)."A. Josephson, Jack (2009). Offerings to the Discerning Eye. Brill. p. 201.

- "the fact that the mother of Ammenemes I, whose name appears to have been Nefert, was a native of the nome of Elephantine"C. Hayes, William (1961). The Middle Kingdom in Egypt. Internal History from the Rise of the Heracleopolitans to the Death of Ammenemes III. Cambridge University Press. p. 34.

- "The mother of Amenemhet was apparently named Nefert and was a native of the nome, or province, of Elephantine""Amenemhet I". encyclopedia.com.

- General History of Africa Volume II - Ancient civilizations of Africa (ed. G Moktar). UNESCO. p. 152.

- Crawford, Keith W. (1 December 2021). "Critique of the "Black Pharaohs" Theme: Racist Perspectives of Egyptian and Kushite/Nubian Interactions in Popular Media". African Archaeological Review. 38 (4): 695–712. doi:10.1007/s10437-021-09453-7. ISSN 1572-9842. S2CID 238718279.

- Lobban, Richard A. Jr. (10 April 2021). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Nubia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538133392.

- Morris, Ellen (6 August 2018). Ancient Egyptian Imperialism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4051-3677-8.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc (2021). A history of ancient Egypt (Second ed.). Chichester, West Sussex. p. 99. ISBN 978-1119620877.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fletcher, Joann (2017). The story of Egypt : the civilization that shaped the world (First Pegasus books paperback ed.). New York. pp. Chapter 12. ISBN 978-1681774565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smith, Stuart Tyson (8 October 2018). "Ethnicity: Constructions of Self and Other in Ancient Egypt". Journal of Egyptian History. 11 (1–2): 113–146. doi:10.1163/18741665-12340045. ISSN 1874-1665. S2CID 203315839.

- Aidan Dodson, Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press, London 2004

- "Guardian Figure". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Dodson, Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Egypt, 2004, p. 98.

- Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period (1997), p. 15.