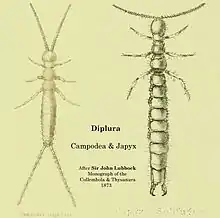

Diplura

The order Diplura ("two-pronged bristletails") is one of three orders of non-insect hexapods within the class Entognatha (alongside Collembola (springtails) and Protura).[3] The name "diplura", or "two tails", refers to the characteristic pair of caudal appendages or filaments at the terminal end of the body.

| Diplurans Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Campodea staphylinus, Belgium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Pancrustacea |

| Subphylum: | Hexapoda |

| Order: | Diplura Börner, 1904 |

| Families [2] | |

Around 800 species of diplurans have been described.

Anatomy

.jpg.webp)

Diplurans are typically 2–50 millimetres (0.08–1.97 in) long, with most falling between 7 and 10 millimetres (0.28 and 0.39 in).[4] However, some species of Japyx may reach 50 mm (2.0 in).[5] They have no eyes and, apart from the darkened cerci in some species, they are unpigmented.[5] Diplurans have long antennae with 10 or more bead-like segments projecting forward from the head.[6] The abdomens of diplurans bear eversible vesicles, which seem to absorb moisture from the environment and help with the animal's water balance.[6] The body segments themselves may display several types of setae, or scales and setae.[7]

Diplurans possess a characteristic pair of cerci projecting backwards from the last of the 11 abdominal somites.[8] These cerci may be long and filamentous or short and pincer-like,[9] leading to occasional confusion with earwigs.[10] Some diplurans have the ability to shed their cerci if necessary (autotomy). Moulting occurs up to 30 times throughout the life of a dipluran, which is estimated to last up to one year.

As entognaths, the mouthparts are concealed within a small pouch by the lateral margins of the head capsule. The mandibles usually have several apical teeth.[7] Diplurans do not possess any eyes or wings.[4]

In males, glandular setae or disculi may be visible along the first abdominal sternite. External genital organs are present on the eighth abdominal segment.[7]

Ecology

Diplurans are common in moist soil, leaf litter or humus,[11] but are rarely seen because of their size and subterranean lifestyles.[6] They have biting mouthparts and feed on a variety of live prey and dead organic matter.[3] Those species with long cerci are herbivorous.[10]

Diplurans are found on nearly all land masses, except Antarctica and several oceanic islands.[7] Their role as soil-dwelling organisms may play a key role in indicating soil quality, and as a measure of anthropogenic impact (e.g. soil nutrient depletion as a result of farming).[12][13]

Reproduction

Like other non-insect hexapods, diplurans practice external fertilisation. Males lay up to 200 spermatophores a week, which are held off the ground by short stalks and probably only remain viable for about two days.[11] The female collects the spermatophore with her genital opening, and later lays eggs in a cavity in the ground.[10][6][11] The hatchlings (or nymphs) do not undergo metamorphosis, but resemble the adults, apart from their smaller size, lesser number of setae and their lack of reproductive organs.[3]

Lineages

Several major lineages within Diplura are readily recognizable by the structure of their cerci.

- Japygidae: possess forceps-like cerci (resembling those of an earwig). Usually very aggressive predatory diplurans, using their pincer-like cerci to capture prey, including springtails, isopods, small myriapods, insect larvae, and even other diplurans.[3]

- Projapygidae: possess stout, short, and rigid cerci.[14]

- Campodeidae: possess elongate, flexible cerci that may be as long as the antennae and have many segments. Feed on soil fungi, mites, springtails, and other small soil invertebrates, as well as detritus.[3]

Relatives

The relationships among the four groups of hexapods are not resolved, but most recent studies argue against a monophyletic Entognatha.[15] The fossil record of the Diplura is sparse, but one apparent dipluran dates from the Carboniferous.[2] This early dipluran, Testajapyx, had compound eyes, and mouthparts that more closely resembled those of true insects.

References

- Hoell HV, Doyen JT, Purcell AH (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-19-510033-4.

- Maddison DR (January 1, 2005). "Diplura". Tree of Life Project. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2006.

- "Guide to New Zealand Soil Invertebrates". Massey University. 2006.

- Bugguide.net. Class Diplura - Two-pronged Bristletails

- Kendall D (2005). "Diplura". Kendall Bioresearch Services.

- "Diplura". McMaster University. 1999. Archived from the original on 2007-03-27.

- Allen RT (Dec 2002). "A Synopsis of the Diplura of North America: Keys to Higher Taxa, Systematics, Distributions and Descriptions of New Taxa (Arthropoda: Insecta)". Transactions of the American Entomological Society. 128 (4): 403–466. JSTOR 25078790.

- "Diplura". The Earthlife Web. November 11, 2005. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05.

- "Diplura". Iziko Museums of Cape Town. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-09-26.

- "Diplura". CSIRO Entomology.

- Meyer JR (2005). "Diplura". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- Roy S (January 2018). "Soil Arthropods in Maintaining Soil Health: Thrust Areas for Sugarcane Production Systems". Sugar Tech. 20 (4): 376–391. doi:10.1007/s12355-018-0591-5. S2CID 19040885.

- Fernandes Correia ME (2018). "Soil fauna changes across Atlantic Forest succession". Comunicata Scientiae. 9 (2): 162–174. doi:10.14295/cs.v9i2.2388 – via Dialnet.

- Smith LM (1960-09-01). "The Family Projapygidae and Anajapygidae (Diplura) in North America". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 53 (5): 575–583. doi:10.1093/aesa/53.5.575.

- Carapelli A, Nardi F, Dallai R, Frati F (2006). "A review of molecular data for the phylogeny of basal hexapods". Pedobiologia. 50 (2): 191–204. doi:10.1016/j.pedobi.2006.01.001.

External links

Data related to Diplura at Wikispecies

Data related to Diplura at Wikispecies